The Legendary Earl Durand – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2001

The Legendary Earl Durand

By Lillian Turner, Former Director of Public Programs

For nine days in March of 1939, the nation was intrigued by the daily unfolding of the story of a “true woodsman” from a remote corner of the West. As Time magazine described him, he was the “huge, shaggy, young Earl Durand” who “was something of a hero, something of a joke in the country around Powell, Wyoming.” Just who was this “Tarzan of the Tetons?” Why was so much attention being given to his story?

He was Walter Earl Durand, born on January 9, 1913, a few months before his parents Walter W. and Effie Durand moved from Rockville, Missouri, to Powell, Wyoming. Earl was their only son. He had two older sisters, Laura and Ina Mae. There would also be a younger sister, Mildred.

The Durand’s were ranchers/farmers who lived northeast of Powell. Earl’s childhood was typical of farm children of that period. He played the usual games—and performed the necessary chores: gardening, feeding, milking cows, and working in the fields.

He loved books—books on folk stories, wildlife, camping, woodcraft, and nature. His interest grew to include books on history. And he read the Bible—five times through—according to his family. He was particularly fond of a small Bible that had been given to his Aunt Emily in 1872; she had given it to Earl in 1917; it was always with him.

Durand was a remarkable physical specimen—six feet two inches tall, blond and blue-eyed; he weighed close to 250 pounds, none of which was fat. He ran miles every day and reportedly could cover 40 miles a night at a lope. He lived in a wall tent behind his parents’ home.

Quitting school after the eighth grade, he devoted himself to a life in the outdoors. His sister Mildred told of his working on farms haying and taking care of cattle on the range to earn money for the things he needed. He’d spend weeks at a time in the Absaroka Mountains west and north of Cody. He fought forest fires in Oregon and traveled on horseback and foot to Mexico and back.

According to his sister Mildred, he had a natural talent for hunting and trapping and became quite expert at both. A family friend stated, “No one could exaggerate what a good shot he was.” It was said he was able to put four rifle bullets through a thrown baseball before it hit the earth. When the rifle ceased to be a challenge, he began to use a bow and arrow.

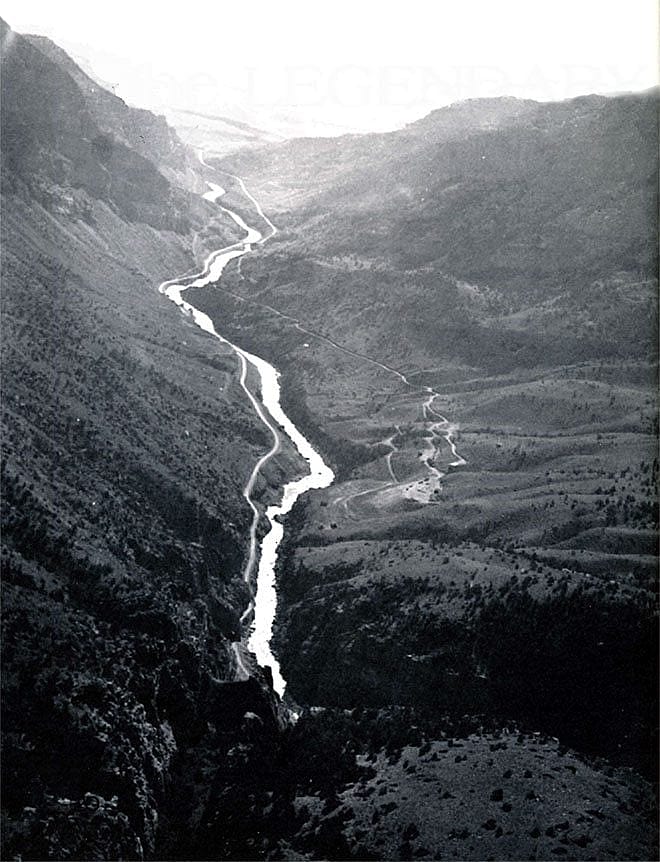

It was a hunting escapade which began the series of events that led to his death. On March 13, 1939, Durand and three companions, Gus Knopp and two teenage boys, killed four elk out of season up the north fork of the Shoshone River, west of the town of Cody, Wyoming, on the road to Yellowstone Park. A resident of the area reportedly notified the authorities. Two game wardens, Dwight King and Boyd Bennion, began an investigation that ended with their waiting at Wylie Sherwin’s Trail Shop at the Shoshone Forest boundary for the hunters to return with the evidence.

To quote the Cody Enterprise: “Finally in pitch darkness, a car came roaring down the highway. The two wardens tried to halt it by standing in its way. Slowing down only slightly, it missed Warden King by only a few inches. Warden Bennion sprang onto the running board, whereupon the occupants tried to throw him off until he poked his gat [pistol] into the driver’s ribs, saying, ‘Stop, or I’ll stop you!'”

Durand, carrying his rifle, jumped from the car on the passenger side and disappeared into the darkness.

The game wardens brought Knopp, the two boys, and the portions of the elk found in the trunk of the car into Cody to the jail. In the absence of Sheriff Frank Blackburn who was in California, his daughter Janet admitted the three culprits. The ten pieces of elk were to be sold at auction three days later.

The next morning a North Fork rancher, Johnny Yeates, found two of his cattle shot. One was dead and missing a single hunk of meat from its flank. He telephoned Undersheriff Noah Riley who, supposing Durand to be responsible, joined the two game wardens in their search. Rancher Leonard Morris and former Game Warden Tex Kennedy added themselves to the party as they tracked Durand eastward down the North Fork highway in the snow. They came into the Shoshone River Canyon just west of Cody where about a half-mile above Hayden Arch they found Durand. Accounts vary, but either Morris or Kennedy was able to get the drop on him, disarming him and bringing him into Cody.

The four were brought before Judge W.S. Owens who sentenced Knopp to two months in jail and a $100 fine for having two elk in his possession. The two youths were paroled after what was described as a blistering lecture by Judge Owens.

Durand pleaded guilty to killing two elk and was sentenced to six months in jail and a $100 fine. The ten pieces of elk salvaged from the four that were killed were auctioned on the post office steps Thursday afternoon for $31.75.

Late in the afternoon on that Thursday, March 16, about 5:30 p.m., Undersheriff Noah Riley brought the prisoners their evening meal. When he opened Durand’s cell, Durand grabbed the milk bottle, hit Riley over the head, took his revolver and an additional rifle, and prepared to escape. With Riley as a hostage, Durand forced him to drive him to his parents’ home near Powell, a distance of approximately 25 miles, presumably to get provisions and gear.

A Very Serious Turn

By now word of his escape complete with the description of the commandeered car had reached Powell. A car fitting that description was reported to have been seen approaching the Durand home. Deputy Sheriff D. M. Baker, age 69, of Powell, and Town Marshal Chuck Lewis, age 44, reportedly a friend of Durand’s, went to the Durand farmhouse to take him into custody. Durand shot them both. Baker died at the scene. In the commotion, Riley escaped. Durand fled. Durand’s parents took Chuck Lewis to the hospital where he died later that night.

With Undersheriff Riley injured, Sheriff Blackburn in California, and Lewis and Baker dead, a question arose as to who was in charge. Oliver Steadman, the county attorney, knowing that Riley was injured, asked former Game Warden Tex Kennedy to take charge. Riley meanwhile had called Big Horn County Sheriff Don Parkins to take over. A conference of sheriffs, deputy sheriffs, and undersheriffs took place in Powell. By 3:30 a.m., a posse of nearly 50 men under Kennedy left Cody in a snowstorm with orders to shoot to kill. Eventually, four groups totaling approximately 100 men were deployed to patrol the nearby hills and the area around the Durand home.

By daylight on Friday, local pilot Bill Monday was searching from the air for tracks in the snow. Neither he nor the posse found any sign of Durand. By Saturday when Sheriff Blackburn arrived from California to take charge, various places around the Powell flat were searched with no results. Sheriff Blackburn requested the use of bloodhounds from the Colorado State Penitentiary at Canyon City.

From Thursday the 16th until Tuesday the 21st, Durand was able to elude the posse – was actually in hiding along Bitter Creek not far from his parents’ home.

The people of Powell panicked. Doors were bolted. Folks went about carrying rifles. The entire area was emotionally high strung—a fact that should not be overlooked.

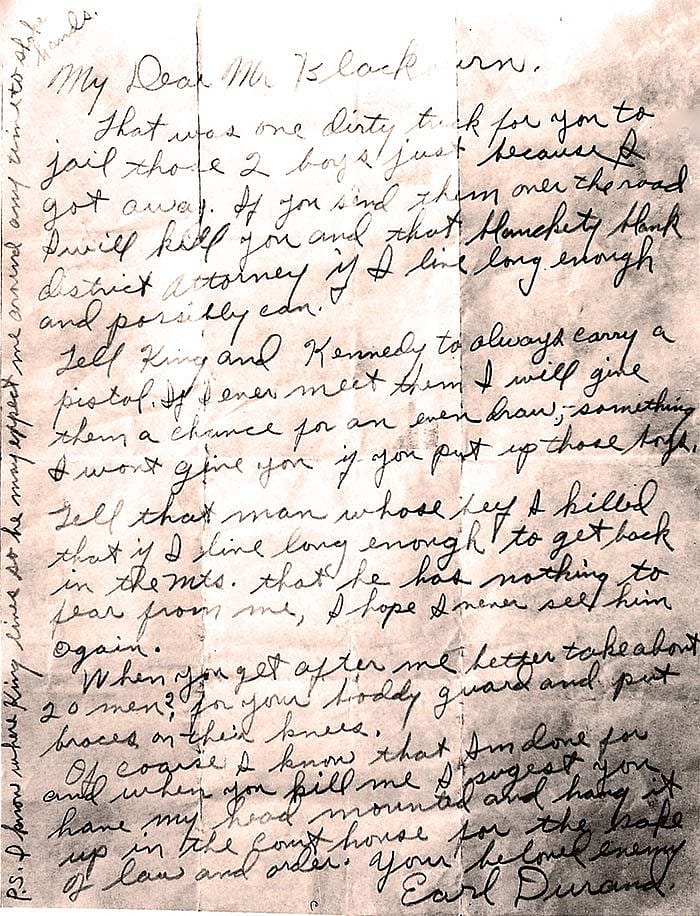

On Tuesday, March 21, Durand appeared at the Herf Graham home where he took a rifle and left a letter to Sheriff Blackburn. The letter ended with this statement: “Of course I know that I’m done for and when you kill me I suggest you have my head mounted and hang it up in the courthouse for the sake of law and order. Your beloved enemy, Earl Durand.” The return address on the envelope was Earl Durand, Undertaker’s Office, Powell, Wyoming.

It was also believed that he made appearances at the Harley Jones’ place and Bill Croft’s home the same night. His parents were staying with the Croft family.

Later that night—close to morning, about 4 or 4:30 a.m., he came into the Art Thornburg home—people he knew—and awakened them. Mrs. Thornburg offered to fix him breakfast—all the while with no lights on. He wanted them to drive him somewhere. Since there was not enough gas in the car, he siphoned some from their truck. They drove him to a place called Little Rocky Creek near the mouth of the Clark’s Fork Canyon, north of Cody near the Montana-Wyoming line.

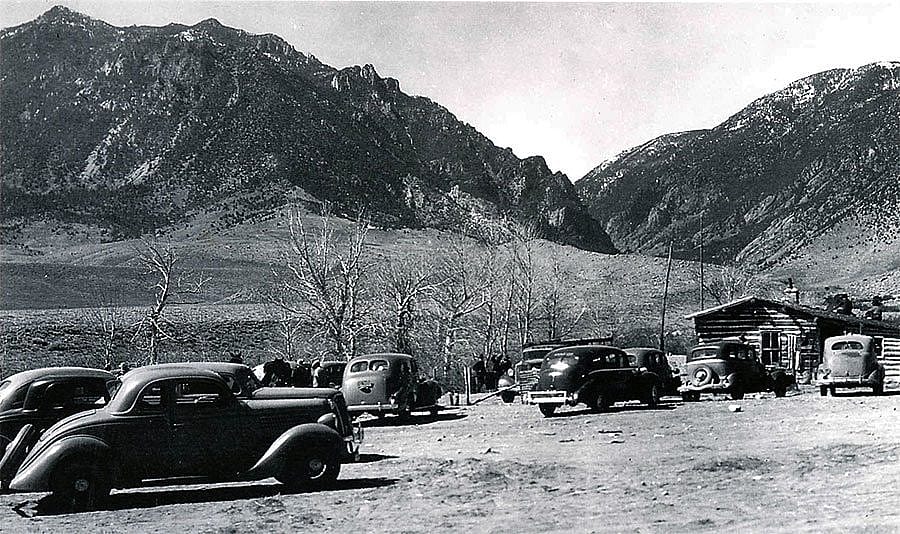

Although the Thornburgs passed telephones at Clark and Badger Basin, it was not until they returned to Powell about eight in the morning that they informed the posse of Durand’s location. The posse quickly departed for Little Rocky Creek where headquarters were set up at the Jim Owens ranch about noon.

To establish communications with town, Dave Carlson and assistant forest supervisor Carl Krueger were stationed at the ranch with a short wave radio. They kept in contact with Harry Moore who had a short wave set located at the Hopkins ranch on the Clark’s Fork. From there phone calls could be made to Cody for necessary supplies. And requests did go out for flashlight batteries, gasoline, and horses. Telephone calls were made to people throughout the surrounding Sunlight Basin and Clark’s Fork areas to alert them to be on their guard.

Because the canyon extended across the Montana border, Montana governor Roy Ayres directed his adjutant general to give all necessary assistance. Captain Charles Wheat and an eight-man detachment from Howitzer Company, 163rd Infantry of the Montana National Guard were dispatched from Livingston, Montana, with a 37mm howitzer, range 1800 yards, and 360 rounds, and a 3-inch Stokes trench mortar, range 800 yards, and 100 rounds. Wyoming’s governor Nels H. Smith authorized the Montana National Guard to enter Wyoming.

The Wyoming National Guard could not be used for criminal cases, but the governor sent a trench mortar, dynamite, and tear gas bombs. Pilot Bill Monday flew to Casper, Wyoming, to pick up the supplies and returned, landing as close as possible to posse headquarters. It was to be his task to drop the tear gas bombs when Durand was located.

A request by Wyoming’s Senator, Joseph O’Mahoney, to General Malin Craig, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, for a howitzer and troops to be sent from Fort Francis E. Warren, was refused on the grounds that it was contrary to law.

The bloodhounds had now arrived from the Colorado State Penitentiary. They were of no help.

Durand was sighted in an inaccessible rocky fortress up the side of a cliff between Little Rocky Creek and the mouth of the canyon. To reach him from above was virtually impossible. To storm his location was suicide. Despite warnings not to try it, Arthur Argento (age 50), a Meeteetse, Wyoming resident and an expert in blasting powders and dynamite, and Orville Linaberry (age 40), a former Montana cowboy and rodeo rider then of Cody, started up the hill. Refusing to listen to warnings from Durand himself, they were both killed. At this point, afraid even to retrieve the bodies, the posse withdrew to their headquarters at the Owens ranch, three miles from the canyon. Here Sheriff Blackburn, in reply to an inquiry by a newspaperman as to whether they had Durand cornered, stated: “We haven’t got him cornered by any means. He’s got us cornered.”

Only later was it learned that Durand had slipped from his perch in the night, taken Linaberry’s shoes, the laces from Argento’s boots, Argento’s deputy badge, their weapons, and disappeared. He followed the posse down to the ranch, unnoticed by them, in hopes of taking Sheriff Blackburn’s car to make his escape. However, there were too many men in the vicinity of the car. Durand proceeded on down the stream at the bottom of the canyon almost to the spot where the Thornburgs had left him originally. There he hid himself in a thicket near the road waiting for a single car to come along. Wednesday night…all day Thursday…Thursday night he waited. Cars came but always in groups of two or three.

During this time the posse discovered Durand was no longer in his fortress. Knowing the survival skills of this man of the mountains, the posse never dreamed he would head in any direction other than deeper into the mountains. Sheriff Blackburn selected twelve top riflemen and headed up into the hills.

On Friday morning, March 24, Harry Moore, the radio operator stationed at the Hopkins ranch, accompanied by John Simpson who was running the Hopkins ranch, and Simpson’s 86-year-old father Peter, was driving toward the posse’s base camp. A man was seen sitting on a boulder by the road. He had a rifle and wore a deputy’s badge. He flagged down the car. Identifying himself as a posse member, he requested a ride to the base camp, asking that they stop down the road where he had left his bedroll. After placing his bedroll in the trunk of the car, Durand identified himself to Harry Moore and requested that the car be turned around and headed toward Powell.

The route from Clark went through Badger Basin along the Sand Coulee route to Ralston. From there they skirted the business district of Powell, driving through the south outskirts on to Deaver, 16 miles away, to the railroad depot where Durand reportedly picked up 300 rounds of ammunition he had previously ordered. He took Harry Moore into the depot with him, leaving the Simpsons in the car.

At Deaver, Durand noticed the car was low on gas and filled it up—paid $2.70 which he told Moore was only right under the circumstances. They then returned to Powell where Durand stopped at his parents’ home to pick up some belongings from the tent in which he lived behind their house. He told his parents good-bye.

Durand next directed Harry Moore to drive north of Powell toward the Pine Bluffs coal mine where they arrived about 12:30 p.m. He told the men he was taking the car and that they could walk the three miles to the nearest ranch. He asked Harry Moore if the car was insured and seemed pleased to find that it was covered by theft insurance. As Durand drove away, he called out, “Come to my funeral, boys,” and honked the horn as he disappeared over the hill.

The three men walked to the nearest ranch. From there they were driven to the closest telephone. By the time they called Powell, Durand was dead.

Just what Durand did during the hour after he left, no one knows. It is believed he visited the site of his hideout on Bitter Creek. At 1:30 p.m., however, he parked Harry Moore’s Buick 100 feet east of the First National Bank in Powell, and with a pack on his back and carrying a .30-.30 rifle, he made his way hurriedly to the bank.

He approached the bank president Bob Nelson and announced he was robbing the bank. There were nine people in the bank at the time—five of them were customers. Armed with the Winchester and with a revolver in a holster on his belt, Durand ordered the employees and customers to line up facing the wall. Convinced by cashier Maurice Knutson that the safe could not be opened because of a time lock, Durand emptied out the cash drawers, taking between $2,000 and $3,000.

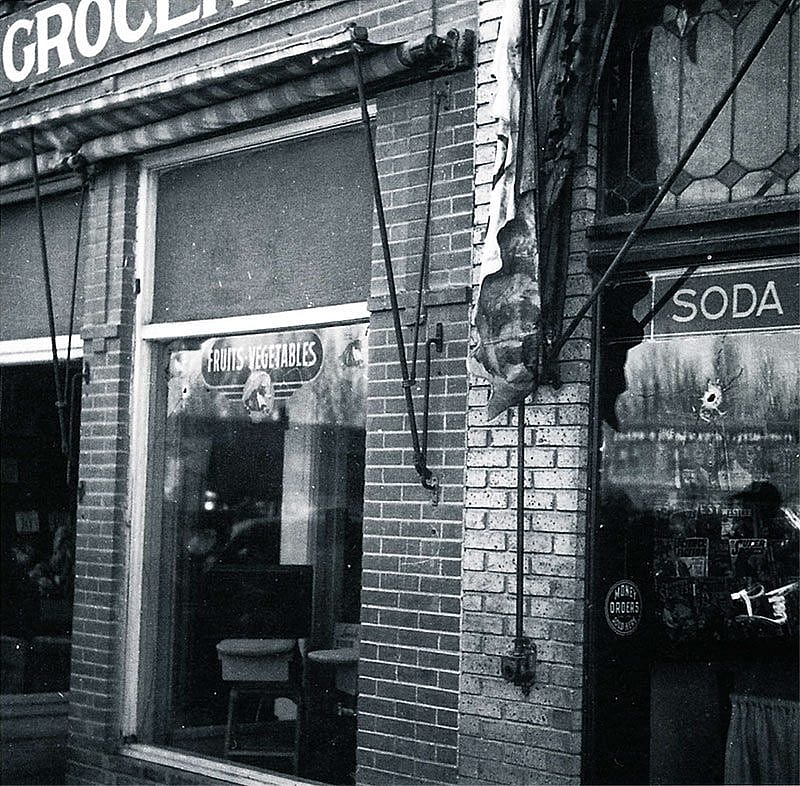

Then the unexplainable happened. Here was Durand with ample funds to finance his getaway, a car waiting outside the bank, nearly all the law enforcement officers in the region 40 miles away at the Clark’s Fork Canyon still convinced he was deep in the mountains, no one aware that he was even in town—and he suddenly opened fire inside the bank. An estimated 40 – 60 rounds hit walls, windows, ceiling—even windows in nearby buildings—for ten minutes or so.

The alarmed citizens of Powell were convinced that gangsters were robbing the bank. They, too, still believed that Durand was in the Beartooth Mountains.

George Blevins, a local correspondent for the Billings Gazette, worked part time in a drugstore across the street from the bank. He called George Beebe, his editor in Billings, to report the bank robbery. The news was also relayed to Billings radio station KGHL. Powell residents listening to their radios that afternoon soon heard what very well may have been the first live coverage of a bank robbery in progress.

Armed citizens converged on the bank—seeking shelter in doorways—some on the roofs of buildings nearby—waiting for the robber or robbers to appear. Finally, four men stepped into the doorway—Bob Nelson, Maurice Knutson, and the young teller, Johnny Gawthrop—their hands tied together with a leather thong. Durand was behind his human shield.

Directly in front of the bank was Otis Roulette’s Texaco station. Among the men inside was a 17-year-old Powell high school junior who was skipping school that warm, sunny, Friday afternoon. Tipton Cox had wandered into the gas station as the robbery was in progress and hit the floor along with the others when the shooting began. For some reason, Roulette gave Tip Cox a rifle just as Durand and the men left the bank. Guns were fired at the men from all directions in the panic that ensued. Unfortunately, Johnny Gawthrop was mortally wounded.

Tip Cox stood in the doorway of the gas station. As he related the story, he fired on Durand only when Gawthrop fell and he realized that Earl was aiming his rifle at him—and he could not be sure that Earl did not mean to shoot. The bullet felled Durand but did not kill him. He crawled back into the bank where he took his own life.

People poured into the streets. Many were still not aware that the bank robber was Durand. George Blevins, at the request of the Billings editor, took pictures of Durand and the gathering crowds. He then rushed the film to Billings, aboard his brother-in-law’s motorcycle, in time for the Saturday newspaper.

Durand’s body was taken to Easton’s Funeral Home. There was such a demand from the gathering crowd to see him that once his body had been prepared, Durand was placed on a couch in the foyer so that people could file by. Hour after hour they came; some even flew into Powell to see him. By 2:00 a.m., the Eastons had to get some rest. A colleague volunteered to sit up the remainder of the night.

On Sunday afternoon at 4 p.m., a private funeral was held. After a brief service, a short procession of cars escorted Earl Durand to the Crown Hill Cemetery east of Powell. But only Durand’s body was buried.

The Legend Begins

As one journalist stated in 1973: “Many here profess admiration for Durand. Others seem to be attempting to bury Durand’s memory. If that is the case their efforts are in vain. The legend of Earl Durand is buried in fertile soil. It continues to grow.”

The legend began before Earl Durand died. Newspaper reporters camped out in Cody during the manhunt sent out releases portraying him as a raw-meat eating wild man of the mountains. He reminded them of Tarzan and “Tarzan of the Tetons” he became, although the title was geographically inaccurate.

It was an era of bank robberies and gangsters and movies that told their stories on every small town movie screen in the country. But here was the same story with an Old West twist…a mountain man Robin Hood bank robber who poached elk and deer to feed those in need.

On the day of the bank robbery, young Tipton Cox was mobbed by reporters and press photographers asking him to re-enact the shooting scene at the gas station. By Saturday morning he was being flown to Denver to make an appearance on radio station KLZ. Directors of the national radio program “We the People,” through their Denver representative Charles Inglis, approached Cox’s parents with a proposition that they fly him to New York to appear on their Tuesday night program. During the four days he was in New York, newsreel footage was made of him that would be shown in theaters nationwide.

Within three months after Durand’s death, more than newsreel footage was available to local theaters across the country. Republic Studios released one of John Wayne’s last B westerns on June 29, 1939. The film’s title was Wyoming Outlaw. Although there is a disclaimer at the beginning of the film that it does not represent any person living or dead, the film’s title and content clearly indicate that the screenwriters were drawing from newspaper accounts of Durand’s story. “Tarzan of the Tetons” became Wild Man Parker for the movie. Already he was acquiring superhuman abilities as can be noted at the beginning of the film when Parker/Durand picks up and carries off not just a portion of meat as Earl had done but an entire steer that he has killed.

Available on the newsstands at the same time the film was released was the July issue of Inside Detective magazine containing Tipton Cox’s own story, “I Bagged Wyoming’s Terror of the Tetons.” Also, in the same month, the magazine Official Detective Stories carried Al Totten’s article, “Wyoming’s One-Man Reign of Terror,” the only article officially sanctioned by the Park County peace officers.

Although the story was told and retold in the communities most affected by the events of that March in 1939, it only occasionally reached a major publication such as the February 1950 issue of True, the Man’s Magazine, which carried Donald Hough’s story, “The 11 Days of Earl Durand.”

But Durand’s legend continued to grow. The accounts usually described him as a young giant who was not only the biggest but also the best: the best marksman, runner, outdoorsman. He was credited as being an Olympic class skater. So strong was the memory of his story, that whenever a manhunt or jailbreak occurred in that part of the West associated with him, the story of Earl Durand often surfaced again in the newspapers.

For twenty years little was written about Earl Durand. Then in the 1970s he re-emerged. Chet Huntley, noted television newscaster, was planning to write a book about Durand when he retired. Hollywood decided again to portray him in film. This time, as with the 1939 Wyoming Outlaw, it is evident that the screenwriters at least familiarized themselves with his story, even using as dialogue verbatim quotes from newspaper accounts of the events surrounding Durand’s escapades. But the screenwriters were apparently more intrigued by the fiction than the facts. The result was The Legend of Earl Durand, which premiered at the Teton Theatre in Powell, Wyoming, on October 8, 1974. Upset by the film’s failure to tell the real story of Durand, some Cody and Powell residents walked out on the film.

But then that has always been the problem with Durand. What is the real story? Even 62 years after it all happened there is just as much division over who was this Earl Durand – Robin Hood hero or cold-blooded killer. His legend is a product of over sixty years of media attention. It is as difficult to sift through these contradictory accounts of his life to find the truth as it has been with other legendary westerners such as Jesse James, Billy the Kid, or Butch Cassidy. Therein lies the dilemma—print the truth or print the legend?

Post 142

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.