Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody, part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Winter 2005

Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody: Mirrored through a Glass Darkly, part 1

By Sandra K. Sagala

Guest Author

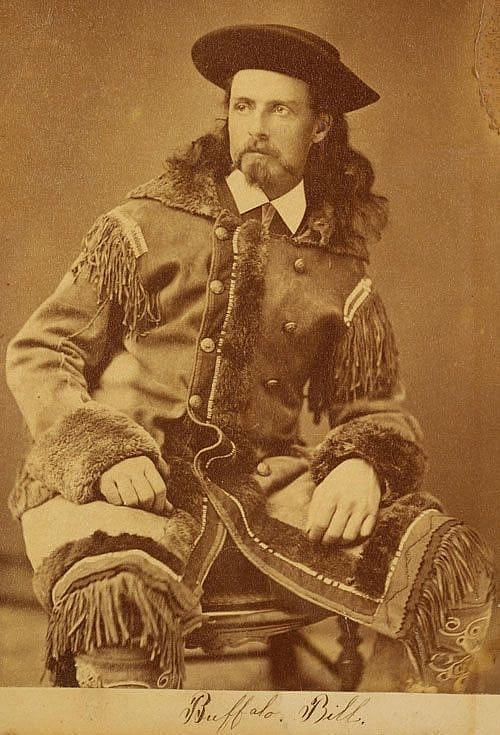

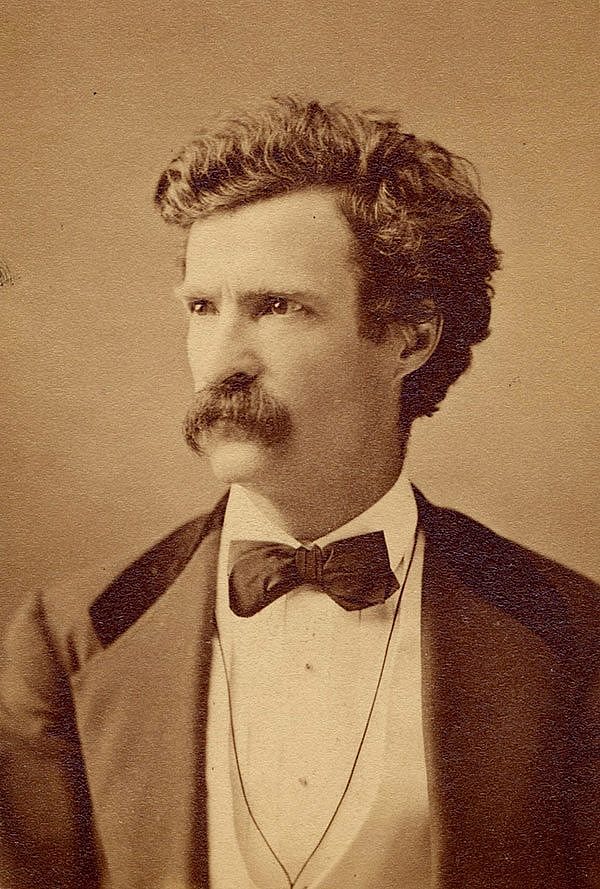

William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Mark Twain, born Samuel Clemens, were two of the most conspicuous men of their time, and prime residents of what Twain called “The Gilded Age. Though eleven years and nearly two-hundred miles separated the men at birth, their lives were remarkably similar. —Sandy Sagala

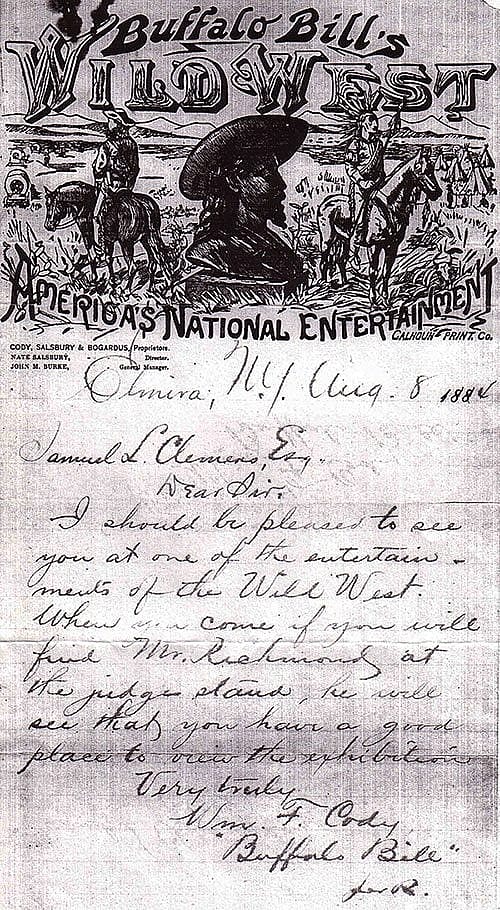

To Samuel L. Clemens, Esq.

Dear Sir,

I should be pleased to see you at one of the entertainments of the Wild West. When you come if you will find Mr. Richmond at the judges stand, he will see that you have a good place to view the exhibition.

Very truly,

Wm. F. Cody

‘Buffalo Bill’

Dear Mr. Cody:

I have now seen your Wild West show two days in succession, enjoyed it thoroughly. It brought back to me the breezy, wild life of the Rocky mountains, and stirred me like a war song. The show is genuine, cowboys, vaqueros, Indians, stage-coach, costumes, the same as I saw them in the frontier years ago.

Your pony expressman was as interesting as he was twenty-three years ago. Your bucking horses were even painfully real to me, as I rode one of those outrages once for nearly a quarter of a minute. On the other side of the water it is said the exhibitions in England are not distinctly American. If you take your Wild West over, you can remove that reproach.

Yours truly,

‘Mark Twain’

If Mark Twain had indeed become, in his own words, “the most conspicuous person on the planet,” Buffalo Bill Cody ran a close second. In their later years they resembled each other enough, both physically and in celebrity, that, in the early 1900s in London, an elderly woman approached Mark Twain saying she had always wanted to shake hands with him. Proud of being recognized, Twain responded, “So you know who I am, madam?” “Of course, I do,” answered the lady unreservedly, “You’re Buffalo Bill!”

When a Plumas National journalist reviewed Twain’s book A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court in 1890, he commented, “Mark Twain has come up from the people. He is American to the backbone.” The very same could be said of Buffalo Bill. Both men were born into humble surroundings but died world famous. Eleven years and approximately two hundred miles separated the two American nineteenth-century entertainers at birth, but the lives of Buffalo Bill Cody and Mark Twain remarkably mirrored each other’s.

In their younger years, the British lady may not have confused them. Author Bret Harte described Twain as having “curly hair, the aquiline nose, and even the aquiline eye…of an unusual and dominant nature. His eyebrows were thick and bushy. His dress was careless and his general manner one of supreme indifference to surroundings and circumstances…he spoke in a slow, rather satirical drawl, which was itself irresistible.”

In 1885, his daughter Susy wrote that he has “…a Roman nose, which greatly improves the beauty of his features; kind blue eyes and a small mustache. He has a wonderfully shaped head and profile. He has a very good figure—in short, he is an extraordinarily fine looking man. All his features are perfect, except that he hasn’t extraordinary teeth.”

In 1878, Twain wrote to American journalist and poet Bayard Taylor, describing himself as five feet eight and a half inches tall, weighing about 145 pounds with dark brown hair and red mustache, full face with very high ears and light gray beautiful beaming eyes and “a damned good moral character.”

In contrast, Cody was nearly six feet tall (six feet, one inch in mid-life), and weighed about 180 pounds. His long, dark brown hair flowed over his shoulders and “he looks at you through [brown] eyes clear and sharp, truthful and honest as the sun.” Journalists often commented on his physique, observing how handsome he was. “[H]is fine, intelligent, strong face show[s] a man ready to counsel or command or to cope with any adversary he may meet.”

The man more popularly known as Mark Twain was born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in November 1835 in Florida, Missouri, to John and Jane Lampton Clemens. Before he was four, the family moved a few miles eastward to Hannibal, where his younger brother Benjamin died. Though Sam was an avid reader, his school grades were only mediocre. Spelling was one subject in which he excelled, despite his later confession of not seeing “any use in spelling a word right—and never did…. Sameness is tiresome; variety is pleasing.”

When Sam was only 12 years old, a lung disease claimed his father, leaving the family almost destitute. To help support his mother and siblings, young Clemens hired on as a printer’s apprentice and learned the art of typesetting at the Missouri Courier. For two year afterwards, he worked at the Hannibal Journal, a paper owned by his brother Orion. At age seventeen, bored with Hannibal and the newspaper business, he ran away east to New York City.

Meanwhile, a state away, William Frederick Cody was born to Isaac and Mary Ann Laycock Cody in LeClaire, Iowa, in February 1846. His older brother Samuel died when Cody was seven and shortly thereafter the family moved to Salt Creek, Kansas. Mr. Cody died of complications from a stab wound to the lungs when Will was 11 years old. To help with family finances, the youngster went to work as a messenger for the freighting company of Russell, Majors, and Waddell.

Between work and family chores, Cody attended school but was only a fair student. Many years later, his sister Helen, after reading some western tales he wrote, commented on his poor spelling and lack of punctuation. Cody replied, “Life is too short to make big letters when small ones will do; and as for punctuation, if my readers don’t know enough to take their breath without those little marks, they’ll have to lose it, that’s all.” To escape from trouble with a schoolmate, young Cody ran away west in the company of John Willis, a teamster.

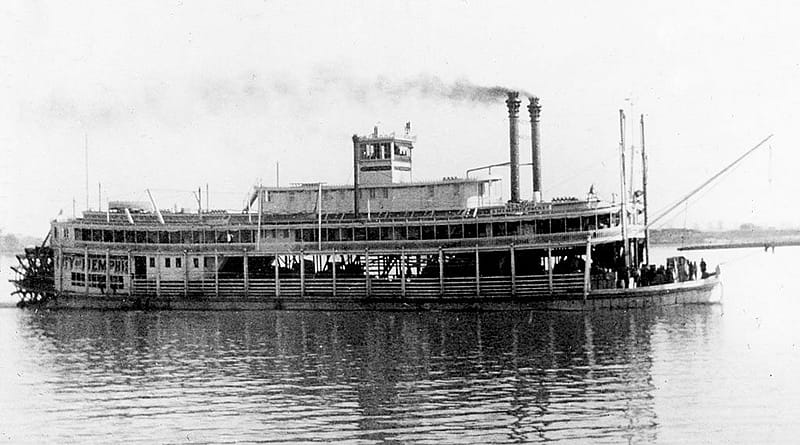

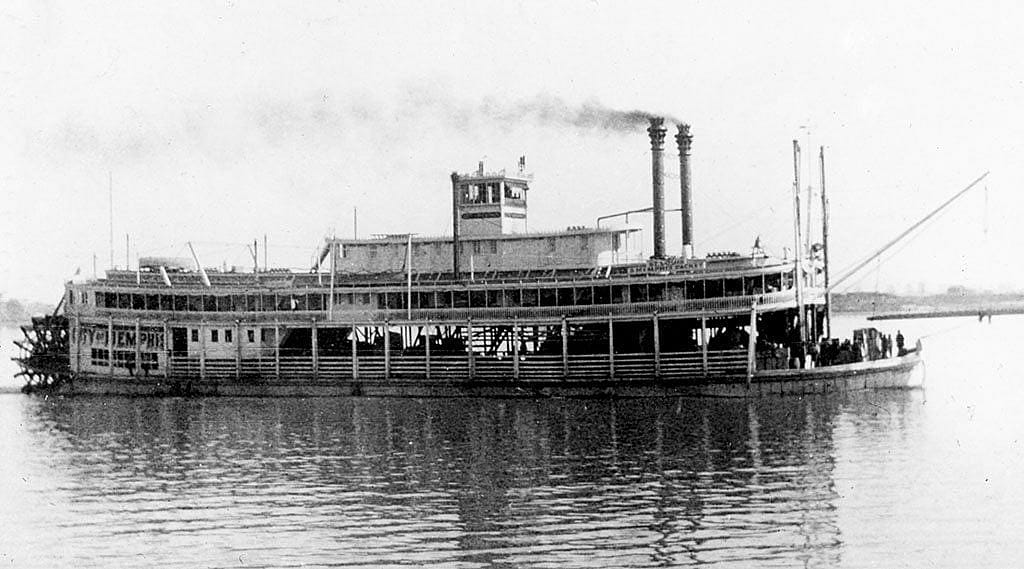

Upon his return from the East, Sam Clemens apprenticed with Horace Bixby as a Mississippi River boatman. “When I was a boy, there was but one permanent ambition among my comrades,” he wrote in Life on the Mississippi. “That was, to be a steamboatman.” For two years from 1859 to 1861, ambition became reality and Clemens was a pilot on his own on the river.

When the Civil War began in April 1861, Clemens joined the Confederate army in Ralls City, Missouri. However, after wearing the gray uniform for only two weeks, he resigned, explaining that he was “‘incapacitated by fatigue’ through persistent retreating.” In a speech to veterans years later, Twain told them how his “unruly band complained of an insufficient supply of umbrellas and Worcestershire sauce and of being pestered by the enemy even before breakfast.” In response to an order to stay put, his detachment instead “disbanded itself and tramped off home, with me at the tail end of it.”

The war had effectively ended commerce on the Mississippi, so when his brother Orion was offered the position of secretary to the Governor of Nevada, Clemens accompanied him west as “private secretary under him.” In chapter eight of Roughing It, he describes his excitement at seeing a Pony Express rider, a “swift phantom of the desert.” Cody claimed to have been one of them and of having ridden an extraordinary round-trip distance. Louisa Cody, in her memoirs about her husband, wrote how Cody bragged, even as youngest rider on the line, he had ridden three hundred and twenty-two miles with a rest of only a few hours in between.

When his finances ran low in Nevada, Clemens unenthusiastically tried mining silver, but found himself unsuccessful at it. Familiar with newspapers, he hired on as a journalist for the Virginia City Enterprise. He turned in weekly reports from Carson City on the legislative session and signed them “Mark Twain,” a pseudonym suggestive of his days on the Mississippi. To “mark twain” meant to note the two-fathom depth which divided safe water from dangerously shallow water for steamboats. To be continued…

In her next installment, to appear in the Spring 2006 issue of Points West, Sagala continues her discovery of even more likenesses between Mark Twain and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody—in particular, their marriages, family life, and attitudes toward non-whites.

Continued in part 2…

About the author

Sandra K. Sagala has written Buffalo Bill, Actor: A Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career and has coauthored Alias Smith and Jones: The Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men (Bear Manor Media 2005). She did much of her research about Buffalo Bill through a Garlow Fellowship at the Buffalo Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. She lives in Erie, Pennsylvania, and works at the Erie County Public Library.

Post 149

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.