Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody, part 4 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Winter 2006

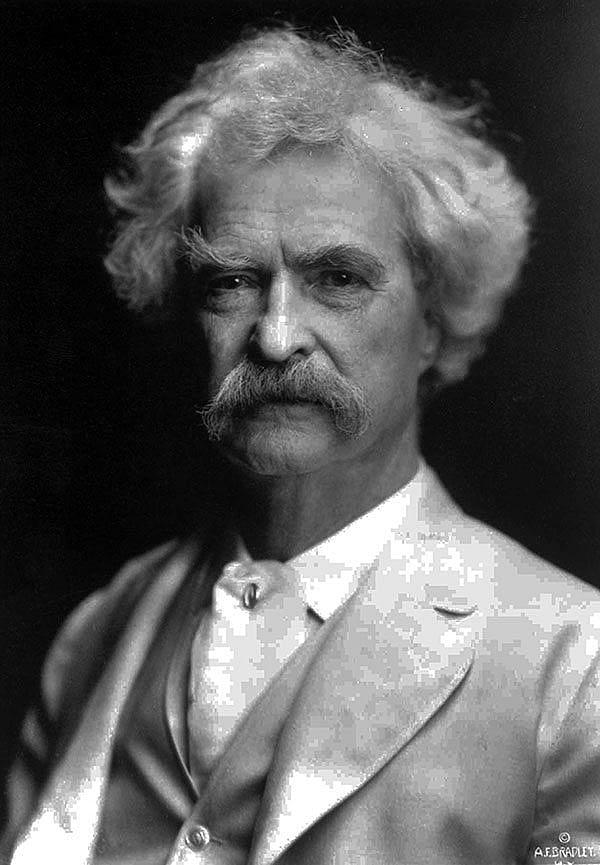

Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody: Mirrored through a Glass Darkly, part 4

By Sandra K. Sagala

Guest Author

In this, the final installment of a four-part series, Sandra Sagala chronicles the later years of Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody, including Cody’s Wild West show and Twain’s exhaustive lecture circuit at nearly 60 years of age. She also discusses their health and financial issues as well as the manner in which they spent their last days—again surprisingly similar.

If you missed the start of the series, click here to go to part 1.

With his stage show growing larger and more popular each year, Cody considered the idea of a grand outdoor exhibition. The success of his “Old Glory Blowout” on July 4, 1882, convinced him of the viability of such a program and soon afterwards he was in full preparation for a huge traveling Wild West exhibition. Cody was exhilarated at the prospect. The downside of his life, however, was his and wife Louisa’s increasing inability to get along and Cody was beginning to talk of divorce. Because of the estrangement, he wanted a place he could call home during the off-season of the Wild West and so authorized construction of a large house in North Platte, Nebraska that he would call “Scout’s Rest.” The Wild West show made Cody a very rich man.

In 1885, 50-year-old Twain, too, was a very rich man—so much so that he was “frightened at the proportions of my prosperity. It seems to me that whatever I touch turns to gold.” He confided to a correspondent that the world might well view him as “the shrewdest, craftiest, and most unscrupulous business-sharp in the country.”

Yet a few short years later, after he sunk thousands of dollars into a lavish home in Hartford, Connecticut, and had lost thousands more on unprofitable patents and inventions—including a steam engine, steam pulley, a scrapbook, and a typesetting machine that chronically broke down—the Clemenses were unable to afford the maintenance of their Hartford house and so moved to Europe. Only his wife Livy’s inheritance kept the family afloat. Then, the publishing company he had started with Charles Webster lost money and went bankrupt in 1894. Though Twain never personally declared bankruptcy, he felt responsible for the debts of the business.

When he should have been considering retirement, Clemens felt obligated to undertake a demanding around-the-world lecture tour at age 59 in order to repay the debtors. It would take from four to seven years to repay the money, but as an honorable man, Twain determined to do it. The tour exhausted him, however, and he wrote a friend that he was “tired of the platform…tired of the slavery of it, tired of having to rest-up for it; diet myself for it…deny myself in a thousand ways in its interest.” But no matter how many times he announced his desire to retire from public lecturing, he continued on because it was lucrative and because he so loved mastering audiences.

Buffalo Bill’s experiences in finances were remarkably similar. Cody was a generous man and gave jobs and money to needy friends and relatives. He helped establish the city of Cody near the Shoshone River in Wyoming, built the Irma Hotel, and poured money into the Oracle mine in Arizona. His Wild West show, while very popular, was extremely expensive to operate, and when profits fell because of poor weather or low attendance, thousands of dollars were lost.

After one particularly down period, he wrote to his sister Julia, “What kind of a Millionaire am I any how? Busted.” Finally, after months of accounts in the red, Cody mortgaged his ranches in North Platte and Cody, as well as the hotel. When the Wild West began to falter irretrievably because of errors in management, rising costs, and stiff competition from rival Wild West shows, Cody realistically, but optimistically, wrote Julia, “I am haveing [sic] hard times just now but I will win out—Can’t down a man that won’t be downed. can they [sic]…”

When his partner, circus man James Bailey, died, Cody was burdened with his debts. Though he was more than 60 years old, Buffalo Bill could not quit the business. His share of the show proceeds was not enough to fund his many endeavors and pay off his debts. In 1907, willing to exploit any venue for a dollar, he collaborated on a book of stories relating his early experiences on the frontier titled True Tales of the Plains. Similar to Twain’s technique, Cody explained, “I work every day in my tent and two hours before I leave my private car, I spend with my secretary, dictating. That’s the way I write stories. Sit down and talk them off.” Cody, too, talked about wanting to retire; in fact, he gave several years of Farewell Exhibitions, but he enjoyed performing and could not leave the saddle.

Both men worked hard, admirably paid off their debts, and eventually were off to new ventures. Twain met the prolific inventor Thomas Edison at least once when Edison recorded Twain’s voice, but the recordings were lost in a 1914 fire. In 1909, Edison’s studio produced a short adaptation of Twain’s novel The Prince and The Pauper. The film included footage of the author at Stormfield, his new Connecticut home in Redding, the only known moving picture of him.

Edison had also recorded Cody as did the Berliner Gramophone Company in April 1898. In the snippet that remains, Cody exhorted all Americans to support the President in the Spanish-American War. With a bit of space left on the recording, Cody can be heard announcing a segment of his Wild West show, “Ladies and gentlemen, permit me to introduce to you a Congress of Rough Riders of the World.”

Cody, like Twain, also appeared on film. With the help of the Essanay (S’n’A) Film Company of Chicago and Hollywood, Cody formed the Col. W.F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) Historical Picture Company and filmed a reenactment of Indian battles in which he had taken part. At the time of release, the epic titled The Indian Wars combined the three campaigns of Summit Springs, the Custer Massacre, and Wounded Knee.

When the Spanish-American War began, Twain was living in Vienna. At first he defended America’s actions as just and righteous. However, he changed his mind when he saw in his “Around the World” tour the status of the British Empire and learned of the shift in American policy in the Philippines away from driving Spain out of the country to claiming the land for itself. Twain claimed to be an anti-Imperialist. “I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land,” he wrote. Over the next few years, he would become disgusted with American policy, writing, “This nation is like all the others that have been spewed upon the earth—ready to shout for any cause that will tickle its vanity or fill its pocket.”

Cody, a red, white, and blue American, did not feel any such disloyalty. Returning home from his first trip abroad, he remarked, “I cannot describe my joy upon stepping again on the shore of beloved America…. ‘There is no place like home’ nor is there a flag like the old flag.” He was ambivalent about the war with Spain but felt obligated to volunteer his services. In a letter to a friend, he wrote, “America is in for it, and although my heart is not in this war—I must stand by America.” When General Nelson Miles learned it would cost Cody $10,000 to close the show, he advised Cody to stay home. The war was nearly over when Miles himself arrived there.

Besides the celebrity that came to Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody, both were formally recognized for their contributions. Yale bestowed on Twain an honorary Master’s degree; the University of Missouri made him a Doctor of Letters; and Oxford University also granted a prestigious doctoral degree. He was so proud of the distinctions that he wore Oxford’s university gown at his daughter Clara’s wedding. Buffalo Bill was awarded the Medal of Honor for his courage in Indian battles. In 1872, without his campaigning for the office, voters elected him to the Nebraska legislature. The election was contested and he never took his seat, but was proud of the victory and used the title Honorable ever after.

In their later years, no doubt aggravated by worries over money, Cody and Twain both had their share of health problems. Cody wrote to his sister, “Am trying to fight that terrible disease Worry. If I can master that, My health would improve right along.” Unfortunately, not only mental stress was responsible for his failing health. Uremic poisoning caused a deterioration of his kidneys and heart, and his ailing prostate put him in considerable pain. Eventually, he could no longer sit in a saddle and rode around the show arena in a buggy.

Twain’s bane was rheumatism which caused him such pain in his right arm and shoulder that he could hardly hold a pen. He tried dictating into a phonograph but found it not nearly as satisfactory as writing. “I filled four dozen cylinders in two sittings, then I found I could have said it about as easy with the pen, and said it a deal better. Then I resigned.”

Mark Twain’s last years were filled alternately with sorrow and joy. He fought with his daughter Clara when she objected to his secretary, Isabel Lyon, whom Twain considered almost a member of the family. When Olivia Clemens died, Miss Lyon assumed many of Olivia’s roles as household manager and commentator on Clemens’ writings. Clara also opposed her father’s relationship with his young “angelfish.” These were the girls between the ages of 10 and 16 with whom he corresponded and who seemingly filled a void when his own daughters were no longer children. He was proud of his home Stormfield, but his delight at having his daughter Jean move back home after years away was cut short when she died on Christmas Eve in 1909. The house became unbearably sad for him, so Twain traveled to Bermuda where he had always found happiness. When he began to suffer from angina pectoris, A.B. Paine, his biographer, brought him home again.

Early in his career, Twain had written: “A distinguished man should be as particular about his last words as he is about his last breath. He should write them out on a slip of paper and take the judgment of his friends on them. He should never leave such a thing to the last hour of his life, and trust to an intellectual spurt at the last moment to enable him to say something smart with his latest gasp and launch into eternity with grandeur.” For all that, Twain only managed a soft “Goodbye” to Clara who was at his bedside at the end. The doctor in attendance thought Twain added “If we meet…” but the sentence wasn’t finished. Samuel Langhorne Clemens, Mark Twain, died April 21, 1910, at age 74.

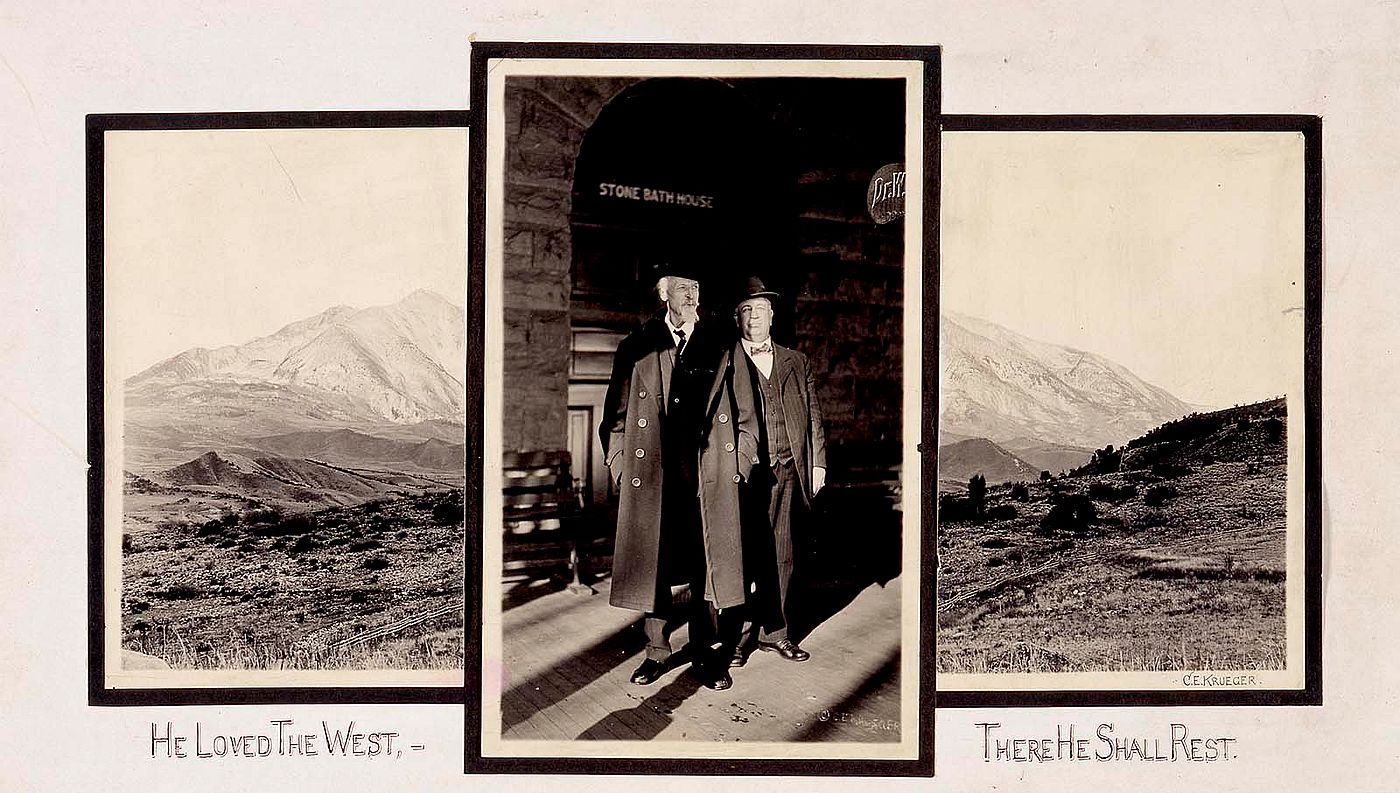

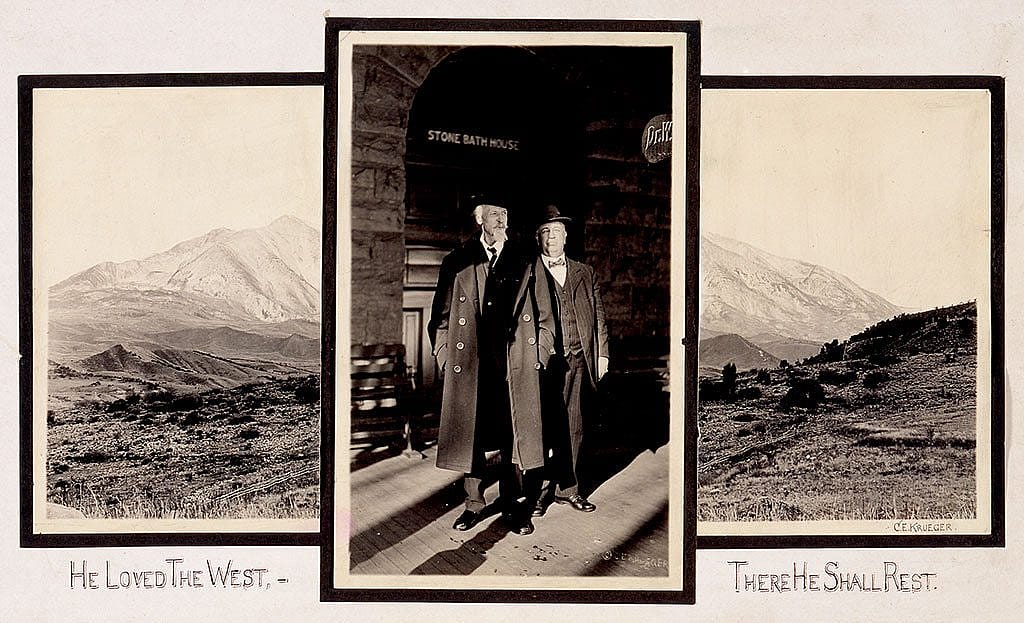

Six years later, November 11, 1916, Portsmouth, Virginia, marked the last performance of the grand showman Buffalo Bill. Following the final bow, Cody headed for his ranch in Cody, Wyoming. Around Christmas time, he traveled to Denver to prepare for the 1917 season. By the time he reached his sister May’s house there, he was physically exhausted. After a while, he seemed a little better and told his wife, with whom he had reconciled, “I’ve still got my boots on. I’ll be alright.” However, by January 5, the Denver press reported the old scout was dying. Cody’s last days were peaceful. Speaking with a reporter, he reminisced about old times on the plains and old friends. On January 10, 1917, with his wife Louisa and his family beside him, William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody died at age 70.

The deaths of both men were major public events and millions of Americans felt a personal loss. Thousands of mourners filed past their coffins. Twain was buried in Elmira, New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery, 100 miles from Mt. Hope Cemetery in Rochester where Cody’s children are buried. Buffalo Bill’s grave overlooks the city of Denver.

When Samuel Clemens was born, Halley’s Comet was visible in the heavens. As 1910 drew near and the comet was due to return, Twain predicted that since he had come in with it, he would go out with it as well, a prediction that proved true. Returning to Nebraska after his first season onstage, Buffalo Bill had boasted to the Omaha Daily Herald: “I’m no d——d scout now; I’m a first-class star.” Indeed, Sam Clemens and Bill Cody can be likened to heavenly bodies, far above ordinary folks, inspiring awe, appreciation, and esteem.

“There are no buffaloes in America now, except Buffalo Bill…. I can remember the time when I was a boy, when buffaloes were plentiful in America. You had only to step off the road to meet a buffalo. But now they have all been killed off. Great pity it is so. I don’t like to see the distinctive animals of a country killed off.” —Mark Twain, quoted in Melbourne Herald, September 26, 1895.

About the author

Sandra K. Sagala has written Buffalo Bill, Actor: A Chronicle of Cody’s Theatrical Career and has co-authored Alias Smith and Jones: The Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men (BearManor Media 2005). She did much of her research about Buffalo Bill through a Garlow Fellowship at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] in Cody, Wyoming. She lives in Erie, Pennsylvania, and works at the Erie County Public Library.

Post 152

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.