Separating Women’s and Men’s Roles on the Oregon Frontier – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 2003

When the Wagons Came to a Halt: Separating Women’s and Men’s Roles on the Oregon Frontier

Cynthia D. Culver, Guest Author

The promise of free land lured thousands of white Americans to travel 2,000 miles in covered wagons along the Oregon Trail between 1843 and 1860. They left family and friends behind on farms in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Missouri to seek financial opportunity in Oregon’s 6,000 square-mile Willamette Valley. Life on the Oregon frontier was challenging. However, generous portions of free land in the Willamette Valley’s fertile soil and mild climate enabled many settlers to experience living conditions superior to what they had left behind “back East.” Not only did they succeed economically, but these Oregon settlers also succeeded in structuring the family in a way that more closely met their ideals than was the case before.

Nineteenth-century Americans believed in distinct social roles for women and men. For the developing middle class in cities like New York, this meant that men should go to work each day in a business or trade, and wives should remain at home, managing the domestic work and raising children. Such role distinctions, however, were not possible for urban laboring classes, not for rural families. Even so, rural women in the East and Midwest did seek to focus their attention on domestic labor, and masculinity for rural men depended on their ability to free their wives from field labor to focus on this domestic work. But this goal of separate work roles remained a far-off dream for many farming families, particularly on the Midwestern and far Western frontiers. Nonetheless, even as women worked in the field and men helped with domestic tasks, they looked forward to a time when these gender role crossings would not be necessary.

Favorable economic conditions in the Willamette Valley enabled many rural families to gradually free women from field labor and men from domestic work. Even as husbands and wives worked together to build successful farms, their work roles became increasingly more gender defined, ultimately becoming clearly differentiated. But this ideal was achieved only with time.

Upon reaching Oregon, settlers sought to reestablish the separate gender roles they had known back east. However, during their first years there, it was a struggle to separate the work roles of men and women. The first few years of farming in the new land required intensive labor to clear, fence and plow the soil. Labor was scarce, forcing women and children to assist men with the field work. Men did the heaviest work, such as harvesting and hauling the cut wheat, but their wives with strenuous domestic work such as laundry and churning butter. To protect their distinct identities as men and women, settlers referred to women’s field labor and men’s domestic work as “helping” their respective spouses. A man’s masculinity or a woman’s femininity was not questioned so long as they were only helping with tasks that were clearly not their own.

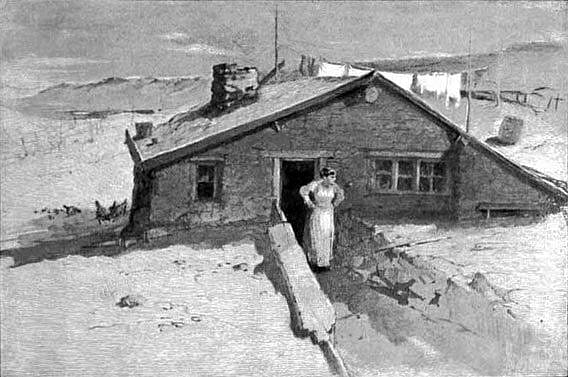

In time, male hired hands became more available, and women gradually withdrew from field labor and focused their attention on domestic work. Men and women divided their responsibilities on the farm roughly based on geography. Men were responsible for work outdoors in the barn and fields, where they plowed, planted and harvested crops such as wheat and hay. Women did work inside the house, including cooking, cleaning and providing childcare. Men produced grain crops and tended and slaughtered livestock, which their wives processed and used to feed their families. One woman who had settled in the Willamette Valley described a typical workday:

Got up at five and got breakfast. Went into the sitting-room and assisted at family prayers. Prepared the little boy’s dinner, washed him and made him ready for school (his mother is away) on their homestead. Skimmed and strained the milk. Went to the henhouse to feed my setting-hens, swept and dusted the sitting-room. Washed the break-fast dishes. Then ironed till eleven Got dinner, rested for an hour Made the beds, worked at mending or some other necessary work for an hour or two, then got supper, washed dishes again etc. This is about a sample, with a change of sometimes instead of ironing I put in the time washing, house-cleaning, gardening etc. with many occasional stoppages and sidetracks.

Men often devoted full days or labor to a single, physically challenging task in the fields such as plowing. In contrast, as this journal entry reveals, women’s lives were filled with a variety of small tasks in and around the home.

As additional male field hands freed Oregon women from field labor, the women were able to focus on domestic work, thus freeing their husbands from “women’s work.”

Withdrawing into the confines of their domestic space, women began to mold their daily lives to conform to the feminine ideal. But rural families could not afford to have women be merely ornamental. They believed that women should be homemakers first and foremost. As one woman explained to her daughter, “of course it is onely right that you should do your share in building up the home + making it a pleasant one for your husband.” Although fathers taught male work roles to their sons, mothers were primarily responsible for their children’s practical and moral education. Settlers believed that women should create a comfortable home to which their husbands would eagerly return after long days of toil in the fields.

Even the most successful farmers relied on a partnership between themselves and their wives to make their farms run smoothly. Yet Oregonians expected men at least to appear to provide for their families without assistance from their wives, and they were highly critical of men who failed to do so. They expected men to support their families with their field labor, allowing their wives to focus on their domestic role. Men who failed to provide for their families were subject to strong criticism, and some even faced divorce proceedings. Over time, Willamette Valley settlers were able to live out their ideal gender roles more fully than they had done in the Midwest, men and women both contributing to the household economy within those roles.

With advancing age, however, farm couples were forced once again to redefine boundaries between men’s and women’s roles. Physical impairments forced those who lived past age sixty to withdraw from the more strenuous aspects of their work. Older women gradually turned from physically demanding household chores to higher-status domestic work, such as decorative needlework or attending to other’s emotional and spiritual needs. And as husbands lost their ability to engage in field labor, they returned to assisting their wives with housework. Thus, while women did work that enhanced their status as proper women; elderly men did domestic tasks that challenged their masculinity. The boundaries that had been constructed to define masculine and feminine roles were being challenged.

And so it happened, that from the time of settlement in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, when men and women frequently assisted one another with whatever needed doing, to well-defined borders between male and female roles, and back again to the blurring of boundaries in old age, the working out of men’s and women’s roles had come full circle. Throughout their lives, settlers continued to negotiate the boundaries of men’s and women’s roles, adapting them to the realities of rural life in nineteenth-century Oregon.

Notes:

1. Maria Locey married in Oregon City in 1860, then later moved from the Willamette Valley to eastern Oregon with her husband and children. She made this record in 1909 while living east of the Cascade Mountains, but her daily routine varied little from that of her fellow settlers who remained in the Willamette Valley. Locey Family Papers 1858–1924, Oregon Historical Society Library, Portland, MSS 2968.

2. Lavina Clingman to Ellenora Crewse, April 4, 1912. Clingman-Crewse Family Papers, Oregon Historical Society Library, Portland, MSS 2645.

Post 154

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.