On the Trail with Lewis and Clark, part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Winter 2006

On the Trail with Lewis and Clark, part 2

By Guy Gertsch

Guest Author

With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Americans began dreaming of the country’s expansion to the West Coast. Once the deal was sealed, President Thomas Jefferson, an advocate of western expansion himself, proposed to send Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on an expedition to “explore even to the Western ocean.” Since 2004, individuals and communities in the U.S. have been commemorating the 200th anniversary of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery—including Guy Gertsch. Part 1 of On the trail with Lewis & Clark told how Gertsch began his journey on May 14, 2004 to follow the trail, “200 years to the day, minute, and place that the Corps began its own trek,” as he put it. In this installment, we catch up with Gertsch on his way to Pierre, South Dakota.

I suppose people who saw me thought I was a bum, albeit a charming bum—a fella just down on his luck, which explains the common offer of money. Even though I was having the time of my life, it was hard to explain to people that I was having fun. I told this one man, who seemed on the verge of offering me his wife, what I was doing. His response was, “Well, maybe people envy you—you’re actually doing it—and wish they were doing it, too. But since they can’t, they still want to be a part of it.” And maybe that really was the case.

The lady in Lower Brule was right about the trip to Pierre, however. Even though I loaded up all my water containers and had enough food, I barely made it. Two days later I came over a bluff and there was Pierre. It looked like an oasis and, in a way, it was. Pierre is a fine place and very hospitable. I spent nearly an entire week there at a long, narrow park located right on the banks of the river. It was a free stay and I was “spent,” so why not?

Moreover, the area is glutted with Lewis and Clark history. This is the place where, at the mouth of the Bad River, an encounter with the Teton Sioux had all the makings of many miseries for the Corps, but which was luckily circumvented. I visited that spot, plus the marvelous State Capitol Building and a cathedral designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and spent a weekend watching water-skiers and boaters up and down the river right by my tent. At last I felt energized enough to move on to Mobridge, where I enjoyed another weekend loitering around the area. While there, I visited Sitting Bull’s gravesite.

The only thing I didn’t like about my South Dakota travel was the myriad of dams. It’s hard to escape the damn dams, but the worst of them, at Great Falls and on the Columbia, were yet to come. I was off to North Dakota, though, crossing the Grand River on July 23. The next day I passed by the site of Fort Manuel Lisa, where most historians believe Sacajawea died and is buried. Visiting the grave monument, a simple stone with a brief history, I dropped my pack and knelt.

Next, I stopped at Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation with its sacred stone. The Corps was there on October 15, 1804. As I was leaving the fort, I noticed a fenced gravesite and so explored: “Sitting Bull.” Sitting Bull? I just gasped! Sitting Bull is in Mobridge! An old Indian man came hobbling by, so I stopped him. “What’s Sitting Bull doing here,” I implored hysterically. He looked down at the grave, then responded in deadpan. “He’s dead!” Like Daniel Boone and Sacajawea, everybody wants Sitting Bull. Associative history!

On July 30, I reached Fort Abraham Lincoln, from where the 7th Cavalry departed on its ill-fated trip to the Little Bighorn River. Then I traveled on to Bismarck, where I stayed a couple of days visiting the State Capitol Building with its magnificent Sacajawea monument.

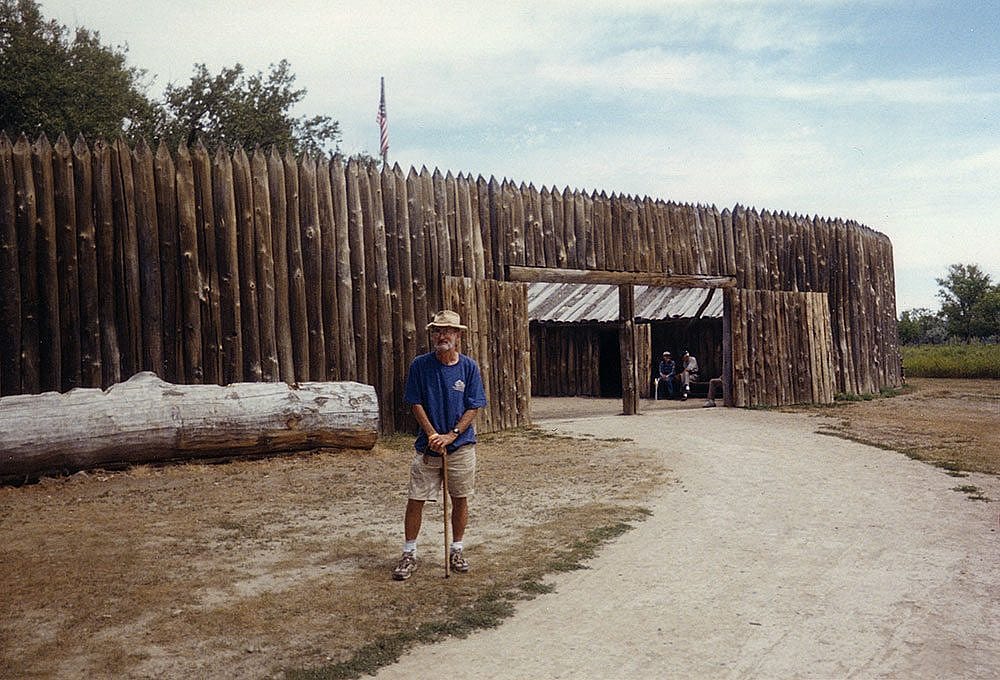

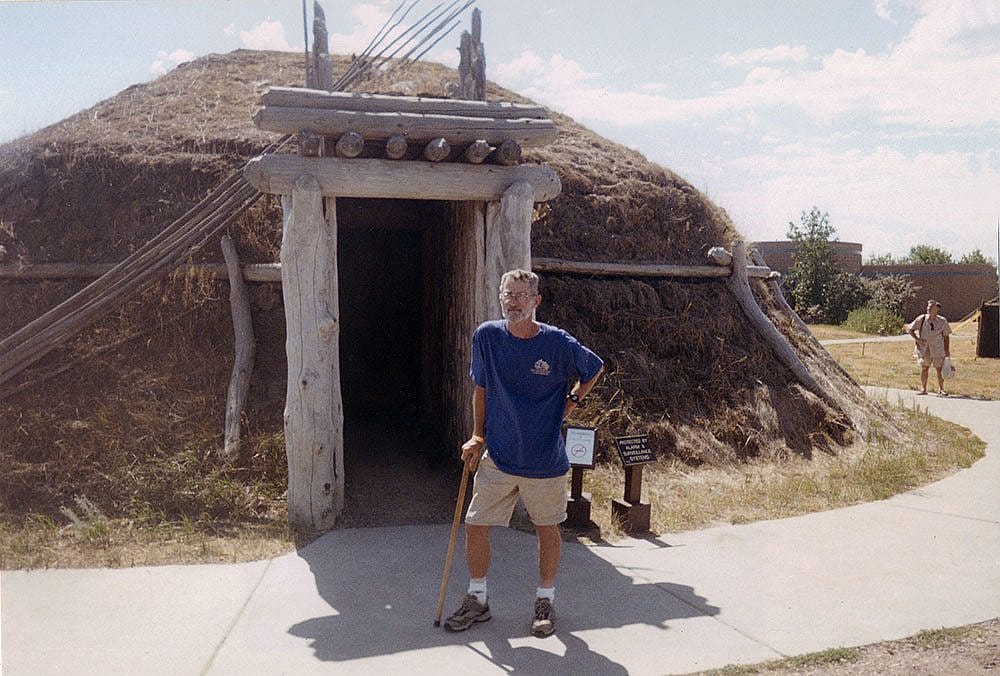

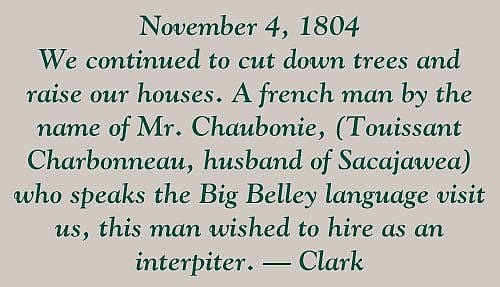

August 6 was a big day for me: Fort Mandan, where the Corps spent its first winter, was in my sights. I was really into some history now! The fort replica has been nicely reconstructed. A journalist there asked me why I was so far ahead of the Corps in travel time. It was simple, really: I just amble along with a backpack, not worried much about encouraging a keelboat or making peace talks with the Indians or plotting the stars for distance traveled. Later I visited the Knife River Village where Lewis and Clark met and recruited Charbonneau and his pregnant wife, Sacajawea—a lucky visit for both them and me.

A few more nights of bunking on the prairie brought me to the Missouri-Yellowstone Rivers confluence. What an adventurous site, and after a visit to Fort Union, I pitched my tent at that confluence. It was getting a little cool, but I hardly noticed. I’d spent many a night on the Yellowstone and there I was again. Something familiar! I was giddy! Fort Union! Yellowstone! Montana!

Damn me if I hadn’t trekked from Illinois to Montana! Eastern Montana was no joy to walk across, but I had been warned. They don’t call it “The Big Sky” for nothing. There were times when I felt myself an ant crawling across a horizon-to-horizon canvas. The place was dwarfing and not a little intimidating—sometimes almost frightening. Walking along the river was impossible, so I took the Highline—and the Highline is interminable. It just disappears into a horizon so far away that it becomes eternity. No wonder so many pioneers “saw the elephant” and took an eastbound egress.

One night my nerves were bothering me so intensely that I was off and “hauling” long before the gray of dawn. Walking across eastern Montana was a fretful experience. The only way to get across was to move as quickly as possible before you became daffy. It was flat and dreary with little villages and sporadic houses miles apart, but close enough that I could stop to fill my canteen. Plus, there was the Milk, “the river that scolds all others,” or so the Mandans told Lewis and Clark, and passed by the Corps on May 8, 1805. That day I literally flew, and made an all time personal best of 42 miles, 31 miles the next day! On September 1, I walked 21 miles along the Milk to Fort Belknap and bunked on the river. I figured 43 miles to Havre where the road turns south to Great Falls, and then I would have done the “Big East.”

From Havre south, the land didn’t change: still flat and dreary. It was getting cold. On the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation, I stopped at a burger joint. I sat down to eat when a young Indian woman asked my destination, and then told me that I wasn’t dressed for the weather. She went to her car and returned with an Old Navy jacket, insisting I take it. I had great hospitality at whatever reservation I traveled through. It seems the less some people have, the more they have to give.

September 6 was memorable; I saw the danger too late. The sky turned black and the wind came out of nowhere. It literally picked me up, pack and all, and tossed me off the road. Then came the rain, and the two of them—the rain and the wind—blasted me for 30 minutes. Lying face down in the dirt and trying to keep from blowing away, I hung on to some brush and braced myself against the onslaught. Both my pack and I were disheveled beyond composure when the vicious intruders began to abate. I couldn’t believe it! Finally, I was able to pick myself up and trudge on to Decision Point where I found a likely spot at the Missouri-Marias confluence, popped up the tent, and tried to sleep, wet as I was.

This was the spot which had so confounded Lewis and Clark: which river to take? The next morning I explored and could imagine their dilemma. In 1805, it must have been an agony. If they chose the wrong one, they would never have gotten across the mountains before the weather got the best of them. I left there and made it to Fort Benton where I dried out.

The next day I was in Great Falls where the Corps made its historic portage, but I didn’t stay there long. It was getting cold and I wanted to make it to Helena. From Great Falls to the Montana capital, there is nothing but a freeway, so I walked along a parallel railroad track and stayed close to the river. A day later brought a blessed sight: the far distant mountain peaks—the Big Belt Mountains were in sight. From Cascade on, I simply walked the river banks. This was Lewis and Clark’s “Gates of the Mountains.” I pulled into Helena on September 10.

Photography courtesy Guy Gertsch.

In the next and final installment, Gertsch arrives at the Pacific Ocean at Seaside, Oregon, the end of the Corps of Discovery’s trip West. If you would like to pose questions to Mr. Gertsch about his trip, send them to the editor.

Post 156

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.