On the Trail with Lewis and Clark, part 3 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2007

On the Trail with Lewis and Clark, part 3

By Guy Gertsch

Guest Author

On the website www.lewisandclarktrail.com, Scott Clark, Executive Director of Glore Psychiatric Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri, writes about the medical concerns of the Lewis & Clark expedition. As he puts it, “President Thomas Jefferson knew that no doctors would accompany the expedition and that there were no hospitals to be found once the crew left the St. Louis area. He therefore sent Captain Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia to spend three months learning—not only the scientific subjects of biology, botany, zoology and map making—but how to take care of his expedition’s health needs. Lewis spent three months with Dr. Benjamin Rush learning when and how to bleed, purge, or otherwise treat a variety of conditions he expected to face the Corps of Discovery.”

Regrettably, Guy Gertsch didn’t have his own Captain Lewis as he retraced the Corps’ trail during its 200th anniversary. In this, his final installment, Gertsch’s plans were unexpectedly stymied in Montana.

I had once harbored fantasies of doing this trip in one season, but no more. Once in Helena, the weather was against me, and so was something else: I got sicker than sick and ended up checking into a Veterans Hospital where I learned I was at the end of the season’s trail. An angry gall bladder spoiled my plans and unlike the Corps of Discovery, I had to wait out the winter.

Once on the mend, I repaired to the road in April 2005. I hitched a ride back to Fort Benton and hung around a dock until I found a boatman who was going downriver. This was a must for me, for I wanted to see the White Cliffs and the Missouri Breaks described so awesomely in the journals, and rightfully so. We went to Judith Landing where I stayed for a couple of days exploring the area. This is another place which the centuries haven’t tampered with much, so again I was in the presence of giants, and alone with eidolons (phantoms).

Back in Great Falls, I became discouraged by the erosion of the past but was impressed with the famous Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center. I returned to Helena with some Cody, Wyoming, friends and resumed my trip on April 7, the same day Lewis & Clark left Fort Mandan, North Dakota.

Then, it was on to Three Forks, Montana, where the Corps found the sources of the Missouri River. I climbed the same knoll from which Lewis surveyed the landscape and described in the journals. From there, it was onward to the Beaverhead and the famous Beaverhead Rock. I climbed the fence and bunked under the rock. It’s not far from there to Camp Fortunate, so named because here the Corps bargained with the Shoshone Indians for preciously needed horses. Sacajawea was reunited with her family and served as an invaluable interpreter.

Now we were moving west! The weather was extremely cold and forbidding; the road was under construction; the day was dark and dreary; and for the first time on the whole trip, I started to feel much chagrin and disheartenment. As I sat by the roadside feeling sorry for myself, the only car I’d seen all day drove up and stopped. A young boy popped open the door and asked if I wanted a ride. I told him no—that I was going over Lemhi Pass.

“Lemhi Pass is closed. Under construction,” he told me.

“Well, I’m going over anyway,” I replied.

The boy was Mexican and conferred with the driver in Spanish. Then he spoke to me again.

“My mother thinks you’d better come with us,” he told me.

The driver was a very attractive Mexican lady and there was another, younger child in the back seat. The lady spoke to the older son—whom I later learned was called Carlos—again in Spanish.

“My mother thinks if you go to Lemhi you will freeze. She says you should come home with us,” he said.

I argued in the negative, but the boy—who appeared to be about 13 years old—jumped out of the car, grabbed my pack, and stowed it in the trunk. “Come on,” he ordered and, obligingly, I got into the back seat. Although he spoke perfect English, his mother, whose name was Maria, didn’t speak a word of it. Carlos interpreted for me, but whatever was being said was not acceptable to his mother. The family took me to their home, fed me, and gave me a bed for the night.

“My father will be home in a while,” Carlos told me. “He will drive you to Chief Joseph Pass in the morning.”

The next day, I thanked them much as I prepared to leave, only to find Maria stuffing sacks of food in my pack. Carlos tried to find room in the pack for an oversized blanket which I couldn’t possibly have taken. “We’ll take you to the Lemhi Road,” Carlos told me—which they did—and sure enough the road was closed.

Dropping me off at the road and not a bit happy about it, Maria got out of the car. I bumbled the best Spanish I could muster, “Muchas gracias! Muy simpatica! Muy Bonita!” I did my Ricardo Montalbán imitation, took her hand and kissed it. She smiled warmly as I went my way. Camp Fortunate indeed! This was a “replay!” Lewis & Clark had their interpreter, and I had mine.

Two days later, I was atop Lemhi Pass, where I spent the night freezing. I was in Idaho, and when I descended the pass to Tendoy, I discovered the previous night’s low temperature had been 10 degrees. Following the Lemhi River, I arrived in Salmon, Idaho, and then made my way back into Montana. It was a long, cold hike from there to Lolo, where I headed west again.

After a wet rainy night at Lolo Hot Springs, Montana, I traveled toward the infamous Lolo Pass. My pack was heavier because my tent leaked and everything was wet. Worse yet, it started raining again! The Pass is only five miles long, but it’s straight up. It took me about an hour to go just one mile, and once at the summit, I was back in Idaho. I wasn’t too fond of the Bitterroots! This part of the trip was also the most taxing for Lewis & Clark—coming and going. Corpsman Gass’ journal called them “the most terrible mountains I ever beheld.”

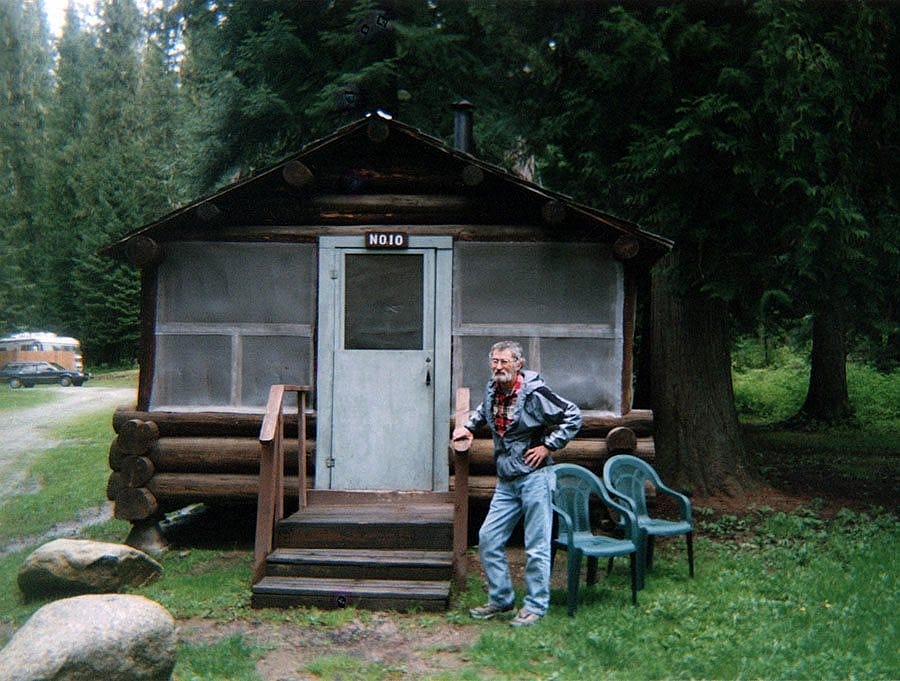

Downhill was definitely better, but there was still a penetrating, cold rain. Searching for anything to serve as an umbrella, I ducked into the Bernard DeVoto Memorial Grove in Idaho, which was well “worth the ducking,” wet or dry. I’ve never found a place more welcome than the Lochsa Lodge there, with its cozy cabins and woodburning stoves. I decided to stay for three days.

The hike along Idaho’s Lochsa River was pure joy—the nights cool, but beautiful. Next, the Clearwater, and then soon into Kooskia and Kamiah, Nez Perce country. I liked it so well, I think I’ll go back there some day. I crossed the bridge over the Snake River into Washington state at Clarkston. A week later, I was on the Columbia and began to smell seawater, fantasizing all the while what the Corps must have been thinking as it navigated the rapids through these gorges.

On the Oregon side of the Columbia between dams, I would catch rides on sailboats, enjoying the scenery, and reveling in where I was. Crossing over into Washington, I found a hiker’s paradise through the gorge, practically all the way to Portland. When I got there, I was far ahead of schedule for I had planned my arrival in Seaside, Oregon—the Corps’ end of the trail—on July 4, which happens to be my birthday. So for the remainder of the trip, I basically “lollygagged along,” singing a song in the sun and in the rain.

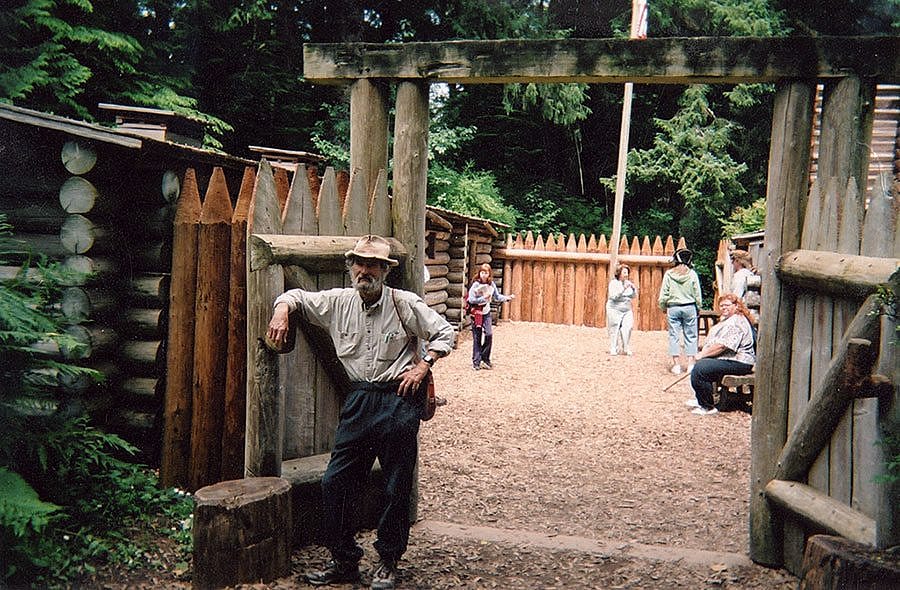

Astoria was great, so I stayed three days. I crossed over Young’s Bay and literally danced on down to Fort Clatsop where Lewis & Clark wintered in 1805. I was a bit of a hero when I got there because my picture had been in several of the area papers. Countless people wanted to talk to me, and I even gave a short presentation at one of the fireside chats. Clatsop was great—nicely reconstructed with excellent interpretations.

I camped that night not far from the Fort. It was exciting because I was so far back in the woods that nobody could see me; it was quiet.

The following night, I stayed at a site on the Lewis & Clark River. I got up the next morning, dressed in my best remaining garb, and polished myself up as best I could. I walked the remaining five miles to Seaside where the July 4 parade was nearly ready to begin. Winding my way down the ultra-crowded street, I could see at the far end of Broadway what I’d been dreaming of for 4,200 miles. When I arrived there, I was pretty much alone as everybody else was watching the parade. There it was: the “End of the Trail” monument that depicts Lewis & Clark facing west toward the ocean.

I dropped my pack at the base of the monument and through my tears, I asked the men frozen in bronze, “How did you do it?” As I reflected, I knew they didn’t do it alone. There were no “supporting players” in the Corps of Discovery. History remembers a few of their names and deeds, but most of them disappeared after 1806, snatched up by winds that blew them into myth.

But I know who they are—all their names and what they did, and the legacy they left behind. I felt them with me at that very moment as I had throughout the adventure. And here I was—Me—a bit player 200 years after the fact.

“I love you guys!” I said aloud. “I wish I could have been with you.”

The parade began. The bands were beating and the marchers were high-stepping.

It was the 4th of July.

“If my health allows,” Gertsch says, “I’m going to do the Appalachian Trail starting in May [2007]. It should take me 4–5 months.”

Post 157

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.