Water, the Wellspring of Life…and Lawsuits – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2005

Water, the Wellspring of Life…and Lawsuits

By Tom Sansonetti

Guest Author

They say water is the wellspring of life. Lately, though, water might just as easily be called the wellspring of lawsuits. Nowhere is that more true than in some of the key water-related litigation and attempts at settlement that occurred during the first term of the Bush Administration.

Lawsuits over water used to be filed primarily in the fourteen western states where the federal Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) had constructed dams and diversion projects. This is no longer the case. Litigation now rages from the Florida Everglades at one end of our country to California at the other. While many of the battles directly involve water allocation, as in straightforward ownership claims, other disputes do so indirectly. Increasing numbers of landowners, justifiably worried about their livelihoods, are concerned when the federal government’s responsibility to protect various threatened or endangered species—especially fish—diminishes the amount of water available to them.

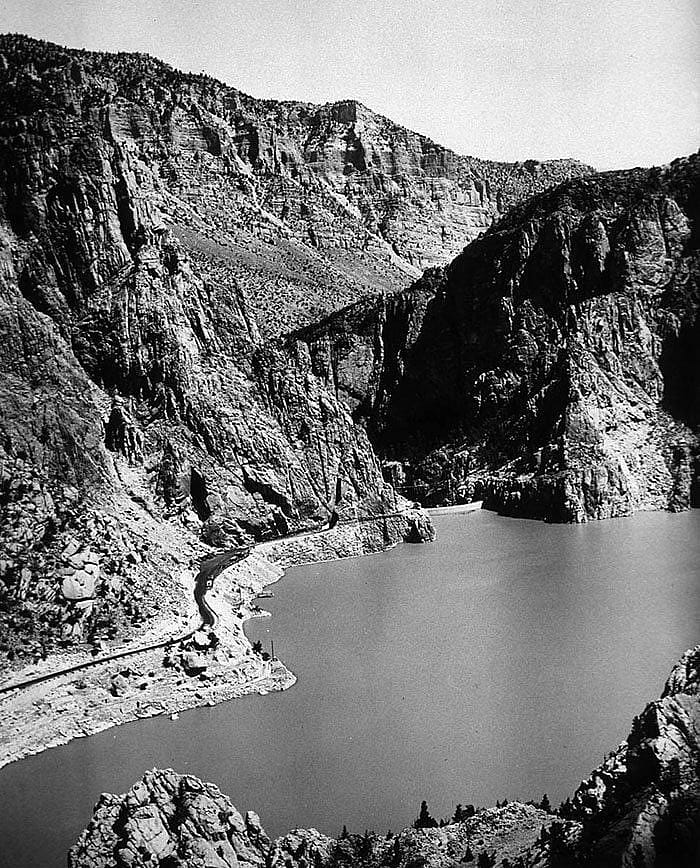

More and more disputes about instream flows to protect fish and their habitat are resulting in lawsuits. These days, the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) federal reclamation program has grown to be the nation’s largest wholesale water supplier. In other words, the DOI administers hundreds of reservoirs and many millions of acre-feet of water in the U.S. Likewise, the BOR often remains a key player in the litigation and related settlement discussions. Much of this water is still delivered for agricultural purposes. However, as western cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix continue to grow rapidly, concerns for a long-term, guaranteed supply of water increase exponentially.

One of the key cases dealing with the legal effects of dedicating water for preservation of ecosystems concerned the 2002 Rio Grande Silvery Minnow lawsuit. Environmental groups sued the DOI in a New Mexico federal district court claiming that federal agencies were not complying with their Endangered Species Act (ESA) obligations. They believed the ESA had the responsibility to protect this particular minnow species from the effects of federal dams being used for water storage and diversion.

The State of New Mexico and the City of Albuquerque got involved in the case on the side of the DOI. It seems the City had already paid to store water for times of drought in the BOR reservoir. In September 2002, however, the federal district judge entered an injunction on behalf of the plaintiff environmental groups. This required the BOR, when necessary, to release the stored water from its upstream reservoirs to meet flow requirements to protect the silvery minnow. The fact that the minnows’ needs were in a stretch of the river below Albuquerque meant the City’s populace would have to watch its prepaid water flow south, unconsumed as the water passed through the City’s boundaries on its way to the fish.

It wasn’t long before the United States appealed the injunction to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver. In a 2-to-1 opinion, the Tenth Circuit upheld the injunction. It maintained that the BOR had sufficient discretion and authority to be required under the ESA to release the water to avoid jeopardy to the minnow. Never mind the fact that the BOR had entered into contracts with several cities—including Albuquerque—to store and deliver water when a need arose.

This “back and forth” continued when, in December 2003, Congress passed an appropriations rider prohibiting the DOI from expending funds to use federal water in New Mexico for the benefit of the silvery minnow. It reasoned that compliance with an earlier March 2003 biological opinion satisfied the ESA. By January 2004, with the DOI’s petition for rehearing in full court pending, the Tenth Circuit, on its own initiative, dismissed the appeal as moot. It said that, on the basis of what amounted to a congressional override of the ESA in its December 2003 action, and the fact that 2003 had turned into a wet year in New Mexico, there was sufficient water for both the cities and the minnows. While the Tenth Circuit additionally vacated its June 2003 opinion, the legal issue of contractual water rights versus the ESA is bound to return to the courts with the arrival of the next drought.

The ESA has also figured prominently in cases being filed by landowners and water districts. Each suit alleges the taking of private property under the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution whenever the federal government curtails water deliveries to comply with the ESA. Essentially, landowners and water districts contend the water in question actually belongs to them like any other asset they might own. One of the most important decisions from those cases was rendered in 2004 by a Court of Federal Claims judge in Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District v. United States.

In that case, the water curtailment was made by the State of California in response to biological opinions issued by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. The judge ruled that withholding water from California farmers, in order to protect the delta smelt and Chinook salmon, constituted a physical taking of the water by the government. The judge stated in his opinion that the federal government “is free to preserve the fish [under the dictates of the ESA]; it must simply pay for the water it takes to do so.”

After a trial on damages, the federal government—and the taxpayers that fund it—were ordered to pay over $24 million, plus interest, and $1.7 million in attorney fees. Faced with this adverse and precedent-setting decision, the United States decided to settle the case for $16.7 million. The settlement, while significantly reducing the trial court’s monetary award, specifically noted that the United States was not conceding liability in this or any other future cases.

The federal government continues to defend similar lawsuits, and the underlying conflict between the ESA and private property rights is not going away any time soon. To the contrary, we are likely to see the ESA amended in Congress by the end of this decade due in large part to the ESA’s impacts on landowners. In June 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court decided a key jurisdictional question about who can sue the U.S. government. The case, Orff v. United States, arose out of the BOR’s Central Valley Project in California. Due to ESA compliance issues on behalf of two species of fish, circumstances once again centered on non-delivery of water under a contract between the BOR and a water district.

The central issue was this: Could member landowners within a water district that was a party to a contract, sue the BOR on their own if the water district decided not to bring suit? This could happen if some of the members of the water district had received all of their expected water and had no reason to file suit. The U.S. Supreme Court resolved the matter in favor of the United States, stating that only the water district itself, and not the individual water users, had standing to sue.

No major river in the United States spawns more expensive, time-consuming litigation than the Colorado River. Fortunately, the news of late has been encouraging due to two key settlements reached by some of the states along the river and the DOI. The case of the Imperial Irrigation District v. United States arose over California’s excessive use of Colorado River water. This 2003 settlement resulted in an agreement that allows California to honor the promise it made in 1929 to live within its basic allocation of 4.4 million acre feet of water, instead of the 5.2 million acre feet it was consuming. The agreement also acknowledged the Interior Secretary’s role as watermaster.

A second beneficial settlement was filed with the U.S. Supreme Court in February 2005 in the case of Arizona v. California. When this suit was filed in 1952, it stood as the oldest original action jurisdiction case before the Court. Parties included California water districts, the states of California and Arizona, Indian tribes, and the United States. The California side of the settlement approves transfer of water from the Metropolitan Water District to the Quechan Tribe in settlement of the Tribe’s and the United States’ reserved water rights claims. The Arizona side of the settlement calls for the additional transfer of water from Arizona to the Quechan Tribe in settlement of similar claims.

These settlements are representative of the positive results that can be accomplished outside the courtroom by skilled negotiators acting on behalf of the Executive Branch of government. The Legislative Branch can also resolve water disputes through acts of Congress. However, when Congress intervenes, the price tag to the American taxpayer is usually quite substantial. With scarce water resources now occurring all over the United States, and ever-increasing populations that place demands on those limited resources, the Judicial Branch will remain the focal point of conflict…and the wellspring of water lawsuits continues!

About the author

Tom Sansonetti served as the Solicitor at the U.S. Department of the Interior from 1990–1993 and as the Assistant Attorney General for Environment and Natural Resources at the U.S. Department of Justice from 2001–2005. He recently returned to Wyoming to practice law with the firm of Holland & Hart LLP in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Post 158

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.