Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists of the West? – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 2003

Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists of the West? Or, Rephrased, Why Is There No Woman Who Is the Equivalent of Frederic Remington or Charles M. Russell?

By Sarah E. Boehme

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

This question can seem startling, because, as a rhetorical device, it brings unstated issues into a forum for examination. It is actually a variation on a question posed over thirty years ago by art historian Linda Nochlin. In a groundbreaking essay, Nochlin asked, “Why have there been no great women artists?”[1] She took the lead in boldly presenting a question, in writing, in a national art magazine, which usually only surfaced in late-night talk sessions and verbal sparring matches on gender issues. Nochlin acknowledged the efforts to research neglected women artists of the past, but noted that there was no woman who could be considered the equivalent of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, or Picasso.

In examining the question, Nochlin revealed assumptions that governed the study of art. She pointed out a prevailing viewpoint—that art is a form of personal expression that comes forth from a genius, and thus she confronted the assumption, lurking behind the question, that women must not be capable of artistic greatness, or else some genius would have emerged. Nochlin asserted that instead of accepting the assumptions behind this question, we should examine the conditions and institutions necessary for the producing art and succeeding with it, such as study and apprenticeship.

Her powerful essay influenced the way art history has been written in the subsequent decades, yet the issues raised by Nochlin have not yet been exhausted and continue to resurface.[2] Since some conditions that produced Western American art are different from those of the European past, it is illuminating to examine Nochlin’s argument and apply it to Western art.

Nochlin drew attention to the types of education necessary for becoming an artist from the period of the Renaissance through the nineteenth century. Drawing from the nude (especially the male nude) was an essential part of artistic training, but was an experience considered inappropriate for women. Therefore, women did not have the opportunity to use a model to understand human anatomy and the postures of a figure. Nochlin pointed out that art develops through a professional system, and in the social conditions of the past, women did not have professions. They were unlikely to gain admittance to the academies or be accepted into the circles of influence that brought awards and patronage.

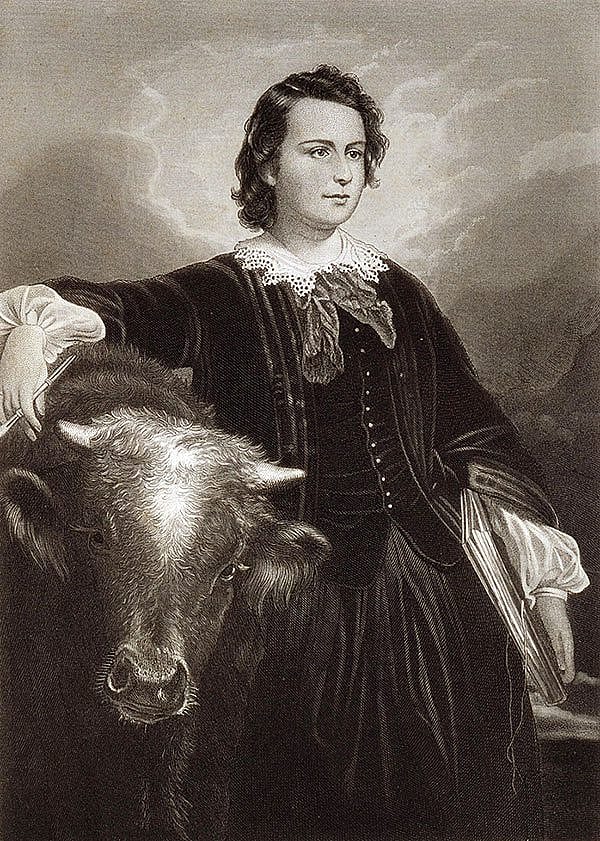

Looking at the careers of the small number of women who did become artists reveals the importance of education and access. Almost all were daughters of artist-fathers (or, in the nineteenth century, had some close connection to an artist). With a father who was an artist, a young woman could learn about artistic materials and processes and she would have an opportunity to train as an apprentice without venturing outside the family. As an example, Nochlin looked at Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), a successful and accomplished French artist of the late nineteenth century “in whom all the various conflicts, all the internal and external contradictions and struggles, typical of her sex and profession, stand out in sharp relief.”[3]

Rosa Bonheur was the daughter of an artist, Raimond Bonheur, and sister of another artist, Isidore Bonheur. Her family situation was influential in other ways; her father was a member of the Saint-Simonian community, a socialist faction that espoused the equality of women. Rosa Bonheur chose to specialize in animal paintings, thus she concentrated on animal anatomy. Instead of drawing the male human nude, she honed her graphic skills by assiduous study in slaughterhouses and livestock sales—unconventional settings for a woman. Bonheur obtained permission from the Parisian Prefect of Police to wear trousers, clothing which she explained did not hamper her work as traditionally female clothing did. Yet she still found it necessary to assert her femininity. Nochlin saw the conflicts in Bonheur’s psyche as factors that subverted her confidence.

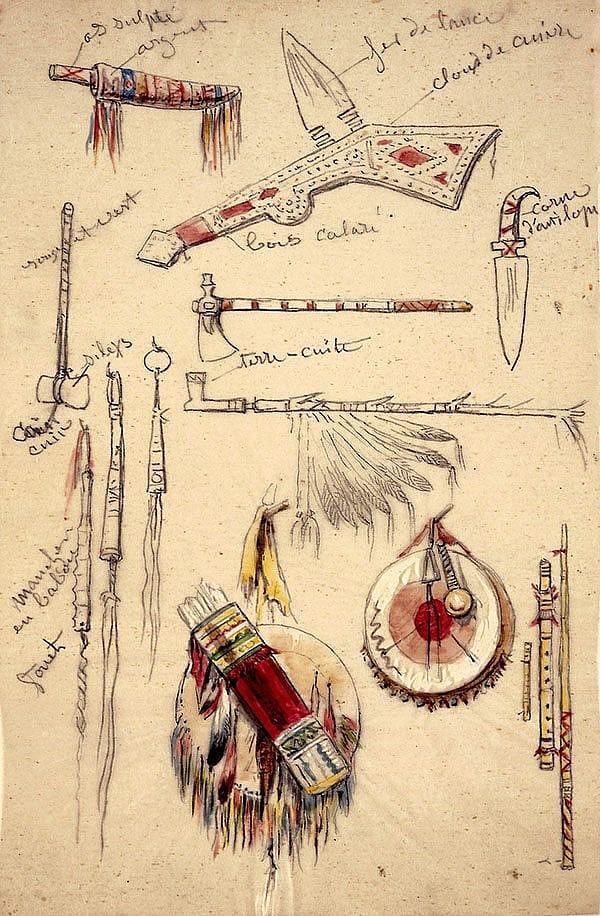

Rosa Bonheur’s unconventionality brought her into contact with the American West, as exemplified by that most famous of Americans, Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, whose portrait she painted. Author Dore Ashton describes Bonheur as an “…Americanophile. She identified America with the liberation of women and with a progressive attitude that conformed to the Saint-Simonian principles of her youth.”[4] Entranced with American Indians as examples of the concept of the “noble savage,” Bonheur had studied the works of George Catlin, carefully copying drawings of Indian implements from his published books. When the Wild West came to Paris in 1889, Rosa Bonheur obtained permission from Buffalo Bill to sketch daily at the encampment, as Bonheur described, “I was thus able to examine their tents at my ease. I was present at family scenes. I conversed as best I could with warriors and their wives and children. I made studies of the bisons, horses, and arms. I have a veritable passion, you know, for this unfortunate race and I deplore that it is disappearing before the White usurpers.”[5] Bonheur was able to tramp among the tents of the Wild West performers, but only in her imagination could she experience the West the way her artistic model, George Catlin, had.

Travel in the West, rather than drawing from the nude or admission into academies, became a factor essential for the artists of the American West, because it supplied firsthand knowledge and the land and its people. Catlin journeyed thousands of miles, visiting over fifty Indian tribes, as he said, “alone, unaided and unadvised.”[6] Alfred Jacob Miller was hired to by Captain William Drummond Stewart to record his adventures in the Rocky Mountains and they traveled with a caravan taking supplies to trade with mountain men. Thomas Moran was able to visit the site that would become Yellowstone National Park because he joined Ferdinand Hayden’s government exploring party. Frederic Remington reported on conditions in the West by traveling with the U.S. Army. Social circumstances in the nineteenth century made it highly unlikely that a woman could attempt such experiences alone or be accepted into the company of traders, explorers or the military.

The type of academic training required in Europe was not easily available in America. Although some self-taught artists, like George Catlin, could achieve success, rudimentary learning was necessary. Painter Seth Eastman, an officer in the United States Army, received his artistic training in drawing classes at the United States Military Academy at West Point. When he was stationed on the frontier at Fort Snelling, he was accompanied by his wife, Mary Henderson Eastman. She had creative aspirations, but channeled those by writing, an art that can be approached without the importance of learning techniques such as perspective and mixing colors on a palette.

Perhaps the most anti-institutional artist, Charles M. Russell built his identity around his experiences as a cowboy, but he really only succeeded with art as a profession after he married Nancy Cooper. Her management of his career prodded the artist to go east, where he learned from other painters, obtained commissions for illustrations, and exhibited his works publicly. That encouragement and access to national exposure took Russell beyond the status of being a Montana folk artist.

By contrast, the effects of the absence of encouragement experienced can be seen in the career of the painter Fra Dana (1874–1948), a woman who sought to reconcile her dream of being an artist with the reality of living in the West.[7] Fra Broadwell Dinwiddie attended art school in Cincinnati, where she met Joseph Henry Sharp, with whom she would continue to have contact throughout her life.

Even though there were women students at the Academy, they were often regarded as “fashionable” young ladies rather than serious students. The women on the faculty were given the introductory classes, not the advanced ones. When Fra Dinwiddie married Edwin L. Dana, a Wyoming rancher, she forged an agreement with him whereby she would be able to travel each year and continue her artistic studies. Fra Dana sought to balance the artist’s life with the domestic life, but in the end she did not maintain this ambitious plan. Although she produced a small body of interesting paintings, she did not develop a career in the way that Joseph Henry Sharp did. Her marriage and the demands of ranch work became distractions from her goals, whereas Sharp’s marriage to Addie Byram provided domestic comfort and promotion for his goals.

Artists like Fra Dana are being rediscovered [See two of Fra Dana’s works in the collection of the Montana Museum of Art & Culture: “On the Windowsill” and “Ah Lach Chee A Koos“]. Their art provides aesthetic enrichment and their biographies give life stories against which we can measure our own. Even the stories of disappointments and discouragement provide instruction when seen against a backdrop not just of personal experience but also of the cultural factors that influence success and accomplishments. Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay reminds us that art is not merely talent, but is work that must be nurtured.[8] The West, which can be inhospitable and harsh in climate and culture, has been an especially unpromising environment for women artists in the past. Perhaps only time will tell if, or how, the situation has changed.

Notes:

1. Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” first published in Art News, Vol. 69, No. 9, (January 1971). Reprinted in Linda Nochlin, Women, Art and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988).

2. In its March 2003 issue, Art News published an article “Who Are the Great Women Artists” with the introduction, “Thirty years ago Artnews published an essay arguing that social forces had impeded women artists from becoming as great as the male masters. We asked experts if the consensus has changed—and how.”

3. Nochlin, Women, Art and Power and Other Essays, 170.

4. Rosa Bonheur: A Life and a Legend, text by Dore Ashton, illustrations and captions by Denise Browne Hare (New York: The Viking Press, 1981), 144.

5. Ashton, 155.

6. George Catlin, Catlin’s Indian Collection, (London: George Catlin, 1848), 2.

7. Dennis Kern, The Fra Dana Collection from the University of Montana Museum of Fine Arts, (Billings: Yellowstone Art Center, 1992). Exhibition pamphlet, also published by University of Montana.

8. See, for example Phil Kovinick and Marian Yoshiki-Kovinick, An Encyclopedia of Women Artists of the American West (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998).

Post 159

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.