Fiddle in the Camp – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2000

Fiddle in the Camp

By Lillian Turner

Former Director of Public Programs

There they lay beside the trail-Aunt Martha’s spinning wheel, Father’s anvil, Mother’s little trunk filled with the family’s heirlooms-testimony to the difficulty of the road ahead and the need to spare the team any unnecessary weight. This was the fate of many a family’s prized possessions on the trail west.

But there was one family treasure that was never left behind for it took up no space nor added any weight. That was the family’s “songbag,” well-worn from use by generations of their kinfolk, some songbags still bearing traces of their European and African origins.

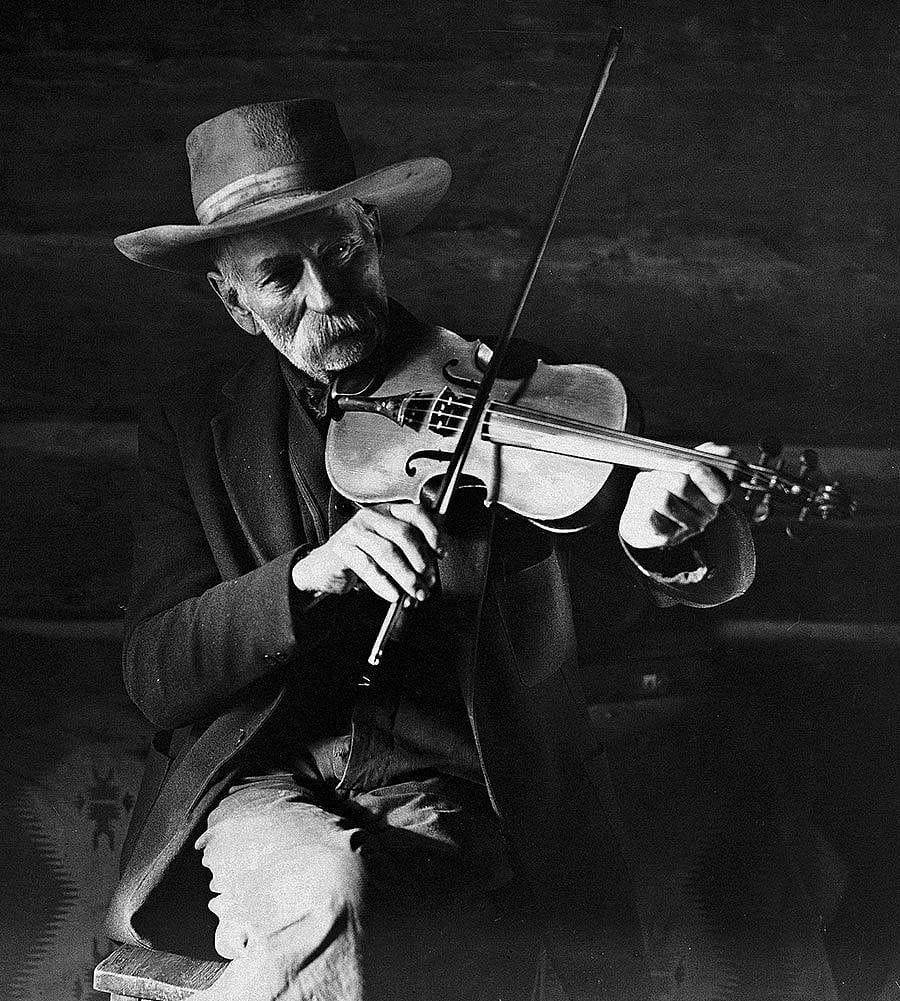

Wherever Americans went, their music traveled with them. Explorers, mountain men, homesteaders, cowboys, loggers, riverboat pilots, teamsters, sailors-music was an integral part of their culture and traveled the rivers, mountain passes, desert crossings, and prairies with them as they sought new land and new adventures.

Songs were born of those adventures and did not always reflect the difficulties of the trek but rather the humor often necessary to cope with the experience. Who doesn’t remember Sweet Betsey from Pike who headed west with her lover Ike and their two yoke of oxen, a large “yaller” dog, a tall shanghai rooster and one spotted hog? Their misadventures enlivened evening campfires and inspired others to tell about

… a pretty little girl in the outfit ahead,

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy,

I wish she was by my side instead,

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy.

Look at her now with a pout on her lips

As daintily with her finger tips

She picks for the fire some buffalo chips.

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy.

But long before covered wagons began their journeys across the plains, music headed west with earlier adventurers. The official baggage list for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804 included a tambourine and a half dozen jaw harps. But packed away in the gear of the Corps of Discovery were two fiddles belonging to Pvts. George Gibson and Pierre (Peter) Cruzatte. On June 9, 1805, they camped on the Missouri River in present-day Montana: “In the evening Cruzatte gave us some music on the violin and the men danced, sang, and were extremely cheerful.” The Corps celebrated the 4th of July: “Our work being completed, we had a drink of spirits-the last of our stock-save a little reserved for sickness. The fiddle was played by Cruzatte, and the men danced until 9 p.m. Festive jokes and songs prevailed, and the men were merry until late at night.”

By mid-October on the Columbia River, there was an exchange of musical cultures: “We halted on a point at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers. There were Indians here and we smoked with them. About two hundred came from their camp, singing and dancing as they came… [Three days later] We landed, and were joined by many natives who brought us some firewood-which was very acceptable, for none is to be found about. Cruzatte and George Gibson played the violins which delighted them greatly.”

Another adventurer was artist George Catlin whose trip to the Pipe Stone Quarry in 1836 was accompanied by music—”the thrilling notes of Mr. Wood’s guitar, and ‘chansons pour rire'” from the boatmen. Catlin’s traveling companion, Mr. Robert Serril Wood, was an Englishman “with fund inexhaustible for amusement and entertainment.” Monsieur La Fromboise, in the employ of the American Fur Company, guided them to their destination.

Catlin recalled: “La Fromboise…has a great relish for songs and stories, of which he gives us many, and much pleasure; and furnishes us one of the most amusing and gentlemanly companions that could possibly be found. My friend Wood sings delightfully, also, and as I cannot sing, but can tell, now and then, a story, with tolerable effect, we manage to pass away our evenings, in our humble bivouack [sic], over our buffalo meat and prairie hens, with much fun and amusement.”

The explorers, artists, and writers who told of their experiences in the West provided an added incentive to those individuals already contemplating a move. Many Americans were seeking change-in occupation, social status, wealth. The West would change their lives, but just as it affected the lives of the people, it also brought changes to their music. But this process had begun long before the music started across the prairies.

Although Oh! Susanna, the song most often associated with the forty-niners and pioneers, was written by a known composer—Stephen Foster, most songs that came west were of unknown origin. There was a sense of the familiar about these songs for many had their roots in Scottish, English, Irish, and Welsh tunes that had been passed on for generations. This is evident as we follow the trail of an English song to the American Southwest.

Just as early explorers searched for the headwaters of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, music historians today backtrack in search of the origins of our songs. Jim Bob Tinsley is one such historian and one of the best at tracing a song along an often-circuitous trail eastward from a version he finds in the West. The following account resulted from his tracking a favorite song of cowboys in the Southwest, The Hills of Mexico, a tale of cattle, storms, stampedes, Indians, and murder. The first and last stanzas set the stage and hint at the outcome:

It was in the town of Griffin in the year of ’83,

When an old cowpuncher stepped up and this he said to me:

“Howdy do, young feller and how’d you like to go

And spend a pleasant summer out in New Mexico?”

And now the drive is over and homeward we are bound

No more in this damned old country will ever I be found.

Back to friends and loved ones and tell them not to go

To the God-forsaken country they call New Mexico.

At the end of his musical sleuthing, Tinsley found that this tale of murder and mayhem began as an old English love song, The Caledonia Garland, which appeared in print in America before 1800. The English themselves adapted that into a sailor’s love song, Canada-I-O, the story of a young woman who followed her lover to sea. The first and last stanzas provide the setting:

There was a gallant lady, all in her tender youth,

She dearly lov’d a sailor, in truth she lov’d him much,

And for to go to sea with him the way she did not know,

She longed to see that pretty place called Canada-I-O.

Come all you pretty fair maids wherever you may be,

You must follow your true lovers when they are gone to sea,

And if the mate prove false to you, the captain he’ll prove true,

You see the honour I have gained by wearing of the blue.

A New England lumberjack encountered this song after having just spent a winter in a Canadian lumber camp. Having found it anything but “that pretty place,” he produced his own version of the song, introducing the first change in tone.

It happened late one season in the fall of ’53,

A preacher of the gospel* one morning came to me. [*a hiring agent]

Said he, “My jolly fellow, how would you like to go

To spend one pleasant winter up in Canaday-I-O?”

To describe what we have suffered is past the art of man,

But to give a fair description, I will do the best I can;

Our food the dogs would snarl at, our beds were on the snow;

We suffered worse than murderers up in Canaday-I-O.

As lumbermen moved west, variants of Ephraim Braley’s song, by now called Michigan-I-O, appeared in lumber camps in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota.

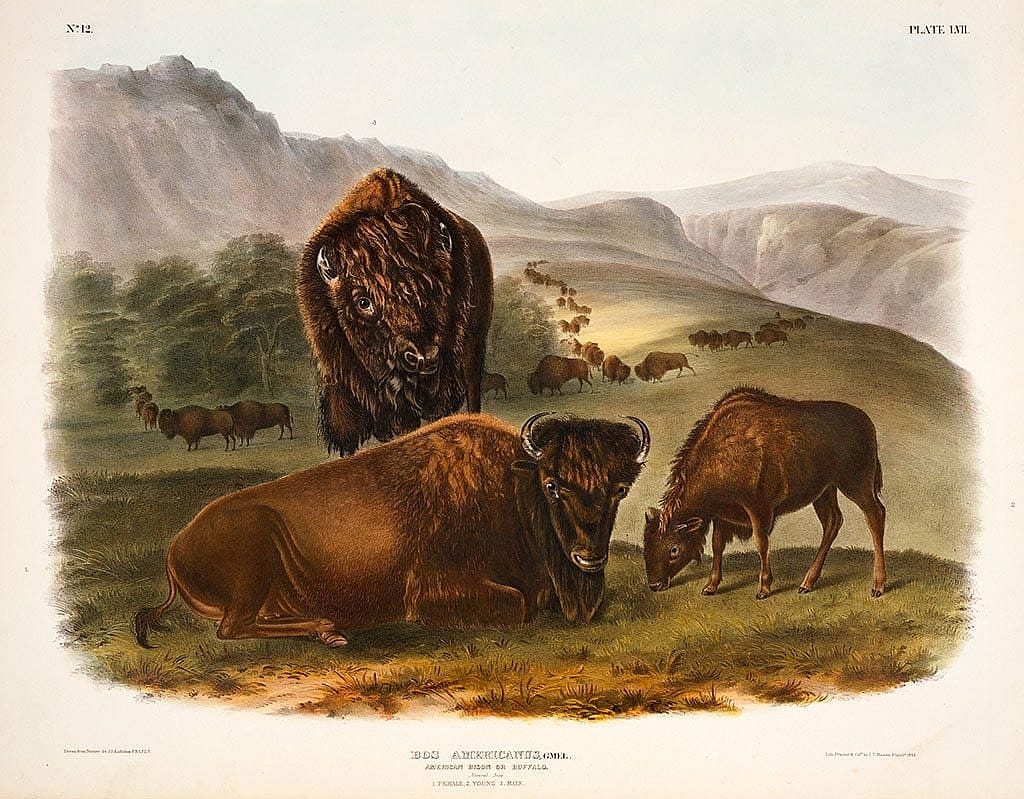

By 1873 the song had moved across country to the plains of Texas and had been adopted by buffalo skinners who added the final twist to the story, the mysterious death of the boss who refused to pay his crew at the end of the season.

It happened in Jacksboro in the year of seventy-three,

A man by the name of Crego came stepping up to me,

Saying, “How do you do, young fellow, and how would you like to go

And spend one summer pleasantly on the range of the buffalo?”

The skinners “left old Crego’s bones to bleach” and told others not to go “for God’s forsaken the buffalo range and the damned old buffalo.” By 1883, the New Mexico cowboys had dealt a similar fate-in song-to their foreman in the hills of Mexico.

The changes in America’s folk music keep it a vital part of our culture. This is evident at the numerous music gatherings across the country each year. Old songs still inspire new ones. Listening to The Leaving of Liverpool, one of the sea songs at the roots of cowboy music, Ed Stabler—musician, singer, songwriter—wrote a cowboy’s version, The Leavin’ of Texas:

“And it’s fare thee well my own true love.

We’ll meet another day, another time.

It’s not the leavin’ of Texas that’s grievin’ me,

But my darlin’ who’s bound to stay behind.”

And the music goes on, growing, adapting, and enriching our culture.

Post 162

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.