A Mysterious Pair of Outlaws, “Escape,” Charles M. Russell – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2002

A Mysterious Pair of Outlaws, “Escape,” Charles M. Russell

Edith Jacobsen

Former Intern, Whitney Western Art Museum

The painting hung on the wall accompanied by a label bearing only the title, artist, and donor. Its file in the vault remained practically empty. Why was this painting created and why was it never listed among the rows of books by and about the famous cowboy artist? The case would eventually lead from books and scholars to archives and galleries, and finally come down to a pair of outlaws.

At the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West], the files on Charles M. Russell’s Escape reveal only a sliver of information. They show that the painting was in the estate of Nancy C. Russell at the time of her death (which helps to verify its authenticity). Later William E. Weiss bought Escape from the Knoedler Gallery in New York and donated it to the BBHC in 1973. The remaining information about the painting comes from the painting itself. Below his signature, Russell scripted 1908. Also, the medium of the painting is black and white oil. This choice of colors implies that Escape was probably created as an illustration. Since most publications at that time did not use color, it made sense to paint the original illustration in black and white thus helping to better maintain the painting’s original color and shading.

With this base of information about Escape, research turned to books written about Russell and his art. One book in particular (Renner and Yost’s A Bibliography of the Published Works of Charles M. Russell) seemed promising because it has attempted to catalogue the titles of all published Russell works, but Escape was not listed.[1] In fact, despite the massive amount of research and scholarship on Russell, a listing of Russell’s painting, Escape, was not found in any of these books.

With little help from books about Russell’s art, the research turns to books about Russell’s life. When this painting was created in 1908, Charlie Russell was on his way to becoming the famed “cowboy artist,” but he was not yet widely accepted. From the time of his arrival in Montana in 1880 at the age of 16, Russell had gradually gained notoriety throughout Montana for his art, but it was not until he married Nancy Cooper in 1896 that his career really began to develop. She helped Charlie to progress from just another talented artist in Montana to a nationally known and respected artist. She began to demand higher prices for his art, put his work in art galleries outside of Montana, and correspond with publishers about her husband’s illustrating abilities.

These efforts eventually led the Russells to New York in 1903 where Charlie was able to learn from other artists, develop his style, and most importantly, introduce his name among the big city art circles. Immediately following their return to Montana in the spring of 1904, Nancy began to correspond with publishers in New York to actively seek out illustrating commissions for Charlie. The Russells were well aware that one way for an artist to become better known was by illustrating in the widely circulated magazines such as Collier’s and Harper’s. It was during this illustrating period that Russell created Escape.

However, knowing that Escape was most likely an illustration does not explain why it was never listed in among Russell’s illustrations. Perhaps Escape was prepared but never actually published. Another possibility is that it was published, but under a different title. Sometimes a publisher would supply his own title if the illustration had no title, or he would change the artist’s title to suit his purposes. One of Russell’s paintings has been published under 22 different titles.[2] Maybe the image of Escape could be found in one of the over 50 books and 100 stories and articles that Russell illustrated.[3]

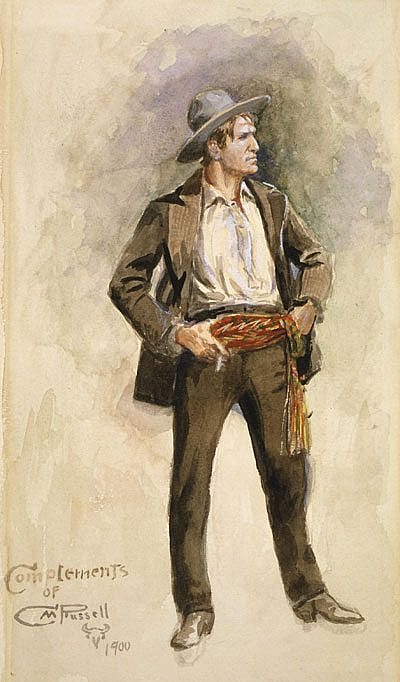

An image strikingly similar to Escape appeared in Russell’s own collection of short stories, Trails Plowed Under, compiled just before his death. I’m Scareder of Him Than I am of the Injuns [click here to view in the Montana Historical Society’s online collection] illustrates the story, “A Pair of Outlaws.” Like Escape, this illustration shows the same cowboy on a bucking horse, gripping the saddle horn, clenching a rope, about to lose his hat. Both cowboys are below an embankment. Both are pursued by Indians on horses.

The short story accompanying the illustration reveals more about both images. In “A Pair of Outlaws,” a man called Bowlegs finds trouble in a saloon, shoots a man, and leaves town on the run. After two days of hard riding, his horse is practically lame, and Bowlegs is anxious to find a new mount. He is in luck when he spots a herd of horses. “One big, high-headed roan” catches Bowlegs’ eye. He corners the roan in a wash and then notices the horse has brand marks all over his hide signaling to Bowlegs that this horse “changed hands a lot of times an’ none of his owners loved him.” Back then, a bad horse was known as an outlaw, so that made for a pair of outlaws. In spite of the horse’s bad marks, Bowlegs recognizes that the horse will be strong and fast, so after a lot of trouble, he succeeds in saddling the bronc. Just then, he notices a group of war-painted Cheyenne Indians heading his way, and reasons, “It’s a sure case of hurry up.” But “The minnit he [the horse] feels my weight, the ball opens.” And Bowlegs begins to describe in great detail the kicking and bucking of “Mister Outlaw.” When the bucking finally stops, the roan takes off “bustin’ a hole in the breeze” and the pair safely escapes.[4]

It is during this description of bucking that a few key clues are dropped. One observer of Escape speculated that the man in the painting was not a real cowboy because a real cowboy would not be hanging on to the saddle horn. Surely Russell would have been aware of this obvious fact after all his cowboy years in Montana. This line from “A Pair of Outlaws” explains: “I’ve made my brags before this that nothin’ that wore hair could make me go to leather [hang on to the saddle horn], but this time I damn near pull the horn out by the roots, an’ it’s a Visalia steel fork at that.”[5] Visalia is a type of saddle and the steel fork is the front part of the saddle that connects the horn to the rest of the saddle.[6] Another line is directly reflected in both illustrations: “Finally he kicks my hat off—either that or he makes me kick it off.” The saddle horn and hat elements find their way into both illustrations and come directly from the narration in the story leading to the conclusion that both Escape and I’m Scareder of Him Than I am of the Injuns were created to illustrate “A Pair of Outlaws.”

Despite the striking similarities of the two paintings and their undeniable connection to “A Pair of Outlaws,” they cannot be the same illustration. The image in the book is a watercolor gouache. Its composition is horizontal, not vertical, and it includes the herd of horses in the background. Also, the horse in the book has his head bowed the opposite direction of the horse in Escape.

Looking further into the origins of Trails Plowed Under and “A Pair of Outlaws” provides clues about the reasons Russell apparently created another very similar illustration for the same story. In the new Bison Books Edition of Trails Plowed Under, Russell authority Brian Dippie explains that the book is a 1926 compilation of short stories Russell wrote throughout his life. Included are four stories that Russell originally wrote and illustrated for the Outing Magazine from 1907 to 1908. Dippie discovered that Russell prepared “A Pair of Outlaws” with an illustration for the magazine, but Outing hit financial problems, so “A Pair of Outlaws” and its accompanying illustration were not bought and published as Russell had planned. Later Collier’s bought the story with the potential of publishing the story without the illustration. But Nancy does not forget the painting. In a letter to one of Collier’s editors, she writes, “He [Charles] has a dandy drawing that goes with it [the story] and it would be to[o] bad to think it could never be used with the story it was made for.”[7] Finally in 1926, the story was resurrected and used for Trails Plowed Under, but Escape did not accompany it.[8]

The new illustration that Russell created for Trails Plowed Under may have been done at the request of the publisher. The watercolor gouache is similar to the other illustrations, mainly watercolor or pen and ink, and the style and medium of the oil painting may have been out of place in the book. Perhaps a horizontal composition was more appropriate for what the publisher wanted for the book. And maybe after 18 years, Russell decided he wanted a different style. Regardless of the reasons, Escape would never be published with “A Pair of Outlaws.”

Just who gave the painting the title, Escape, is still a mystery. In the correspondence between Nancy Russell and the editor of the Outing Magazine, the illustration’s title is never mentioned. However, an art dealer with no idea of its origin would probably give it some sort of title about a cowboy on a bronc being chased by Indians, so it is likely that whoever titled the painting knew its connection to “A Pair of Outlaws.” And considering its complete lack of publicity, it seems likely that as time went on, only the Russells would know the connection, which implies that Escape is the authentic title.

Although it was never published, Escape reminds viewers not only of Charlie Russell’s great career as an artist, but also of his career as an illustrator and author. Whether it was a grand gallery painting, an illustration for a magazine, or a short story, Russell used his talents to preserve the old West with its cowboys, Indians, and sometimes even a pair of outlaws.

Notes:

1. Yost, Karl and Frederic G. Renner, A Bibliography of the Published Works of Charles M. Russell (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971).

2. Lewis and Clark Meeting Indians at Ross’ Hole. Yost, Karl and Frederic G. Renner, A Bibliography of the Published Works of Charles M. Russell (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971),

3. Renner, Frederic G., Charles M. Russell Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture in the Amon G. Carter Collection (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1966), 73.

4. Russell, Charles M., Trails Plowed Under (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927), 85-90.

5. Ibid, 89.

(6) Ward, Fay E., The Working Cowboy’s Manual (New York: Bonanza Books, 1983), 206, 208, 213.

7. Britzman Collection, Accession Number C.6.222, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Nancy C. Russell to Caspar Whitney, 1 March 1909.

8. Russell, Charles M., Trails Plowed Under (Bison Books Edition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), introduction by Brian W. Dippie, viii.

Post 165

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.