Riding the Radio Range – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2003

Riding the Radio Range

By Lillian Turner

Former Director of Public Programs

In this age of satellite television and internet radio with the world’s programming available at the click of a remote or a mouse, it is hard to imagine a time when radio was rural America’s lifeline to music, news, and sports.

Radio was in its infancy when World War I began. Young David Sarnoff, who would become a powerful figure in the development of the broadcast industry, as early as 1916 wrote a memo to his boss at the Marconi Company suggesting the use of radio as entertainment: “I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a household utility in the same sense as the piano or phonograph….” Little did he realize how prophetic was this statement.

However, radio’s development was slowed by America’s entry into World War I at which time all commercial and amateur use of radio was halted. For the duration of the war, the use of radio was reserved for the war effort.

When civilian radio restrictions were lifted in 1919, the pioneer broadcast industry could not have anticipated the rapid growth that would occur over the next 20 years. By 1924 it was already ranked 34th on the list of all industries in the United States. In the post-war years America prospered, especially its middle class. Americans enjoyed the highest national average income in the world. The boom was evident in America’s buying into the new technology. There were nine million automobiles in the United States when the census was taken in 1920. By 1928 the number had risen to 26 million. In 1930, for the first time, the census included the question: “Does this household have a radio?” The prosperity of the 1920s insured that half of America’s homes had a radio by 1930 (12 million Americans had access to radios).

The rapidly growing industry needed a wide variety of programming. England’s successful broadcast of opera star Nellie Melba’s June 15, 1920 concert was considered a “stunt” at the time, but it awakened Americans to the possibilities radio offered. As producers sought to find the perfect format for each new radio station, many chose programs to appeal to the country’s large rural population. Fifty percent of America’s population was rural—farm and non-farm. This number would drop slightly to 45 percent during the 1930s.

Although radio stations experimented with a range of programming which included sports events, sermons, news, presidential addresses, and comedy, music played a large role in most stations’ daily schedules. Many performers and musical groups filled daily program slots, offering everything from barbershop to hillbilly, dance music to gospel, along with traditional and original cowboy songs.

A classic example is station WLS in Chicago. Sears-Roebuck and Company was intrigued by the potential offered by this new medium for reaching the lucrative farming market. Having first toyed with the idea of buying time on radio stations, Sears chose instead to invest in its own broadcast facility. Sears signed on the air on 500 watt WES (World’s Economy Store) on April 9, 1924, and continued running test programs for the next two nights. The listeners lit up the switchboard after hearing the broadcasts. The station officially went on the air on April 12, changing its call letters to WLS (World’s Largest Store). Among the performers on opening night were Grace Wilson singing “At the End of the Sunset Trail” and movie cowboy hero William S. Hart reciting “Invictus.”

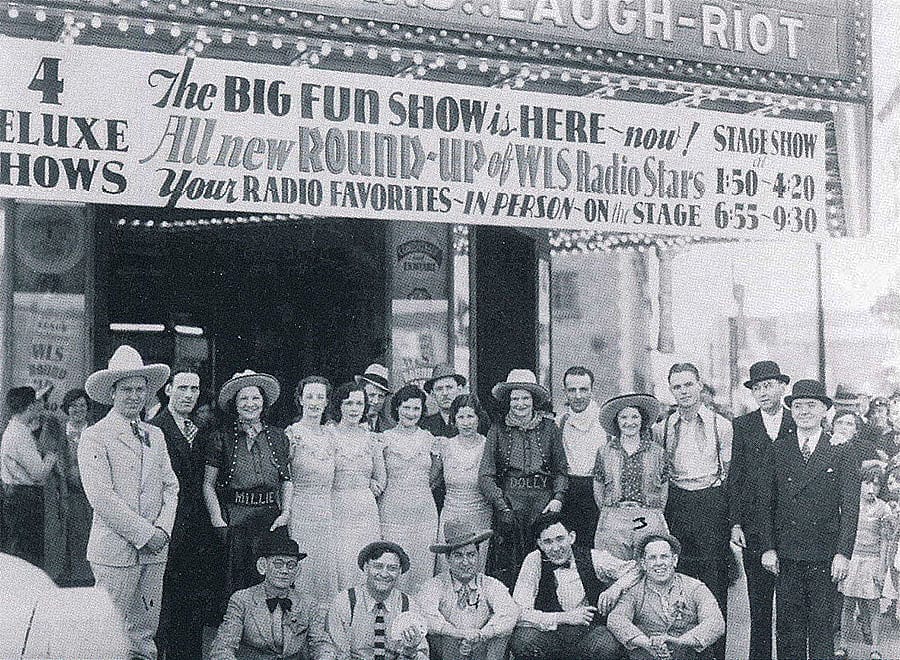

Sears was in on the ground floor of radio, offering programming and selling radios and their accessories. Attuned to the needs of its rural audience, it stated in its 1925 Sears Catalogue: “WLS was conceived in your interests, is operated in your behalf and is dedicated to your service. It is your station.” Growing from an obscure local signal to a Midwestern powerhouse in a little more than four years, WLS reached out to its rural audience with farm news, comedies, radio serials, civic programming, and a wide variety of music. Over 130 musical acts regularly performed for free and nearly 60 different bands made WLS their radio home! Included in the programming was cowboy and western music.

On April 19, 1924, WLS premiered the National Barn Dance which became one of the longest-running and most popular western and country shows in radio history. Its four-hour (later two-hour) format delighted listeners whose response by telegrams on opening night insured the program’s future. The National Barn Dance appealed not only to the rural audience but also to those nostalgic for their rural roots or just for programming that reflected a simpler era instead of the frenetic Jazz Age in which listeners found themselves.

Although Sears sold WLS to Prairie Farmer Magazine in 1928, National Barn Dance remained popular until the station was sold to ABC in 1959. Western musicians whose careers were launched by regular appearances on WLS included Gene Autry, Rex Allen, Pat Buttram, Patsy Montana and the Prairie Ramblers, Eddie Dean, the Girls of the Golden West, and Louise Massey and the Westerners. The popularity of National Barn Dance resulted in similar programs appearing on other radio stations from New York to Hollywood.

The success of such programs as National Barn Dance helped popularize traditional cowboy music and the western music written and performed during the 1930s and 1940s. In addition to the large productions, radio stations also began to feature individual performers who soon developed into popular radio personalities. Two of these were John I. White and George B. German.

John I. White was a performer who developed an interest in traditional cowboy music. Although not a musician by profession, when first given the opportunity to perform on New York radio station WEAF in 1926, White began a music career which lasted until 1936 when he retired from music. His best-known years were those from 1930 to 1936 when he performed as “the Lonesome Cowboy” on Pacific Coast Borax’s Death Valley Days on network radio helping create the public’s image of the singing cowboy. White was among the first of the radio personalities to publish and distribute a folio of cowboy songs, an idea that would catch on with the public and would be copied by other performers. Although the folios were a significant contribution to the preservation of cowboy music, White’s collection of the histories of cowboy songs—information he used in his programs—ultimately resulted in the publication of an important work on that genre, Git Along, Little Dogies (University of Illinois Press, 1975).

George B. German began performing on radio station WNAX in Yankton, South Dakota, in 1928, a station which reached farming and ranching country from western Minnesota and Iowa through the Dakotas and Nebraska into eastern Montana. Like White, German sold hundreds of folios of cowboy songs over the air. Glenn Ohrlin, noted singer and collector of cowboy songs, states in his book, The Hell-Bound Train (University of Illinois Press, 1973): “My own earliest interest in cowboy songs was probably directly sparked by one of his [German’s] folios, which had a bucking horse photo in it, and my aunt Irene’s bag of cowboy and hillbilly songs, which she learned from both the folio and the radio program….”

By the 1930s, in order to capitalize on the increasing popularity of cowboy and western music on the radio, Gerald King, then program director at KFWB in Los Angeles, started a new transcription company, Standard Radio, the purpose of which was to make recordings and to sell or lease these to stations in need of programming. Among the performers making transcriptions for King was the increasingly popular western music group, the Sons of the Pioneers, even prior to their involvement in movies. King would eventually produce a general music library which could be leased to radio stations, but the Sons of the Pioneers’ transcriptions were sold to radio stations. Some of their transcriptions were still being played well into the 1950s.

Radio was playing a significant role in the preservation and promotion of cowboy songs. Live performances whetted the public’s appetite for this musical genre, while the folios and recorded transcriptions kept the music on the air and in the homes for decades to come.

Post 172

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.