Times to Try a Soul, William F. Cody in 1876: Remembering Kit Carson Cody – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2003

Times to Try a Soul, William F. Cody in 1876

Remembering Kit Carson Cody

By Juti A. Winchester

Former Curator, Buffalo Bill Museum

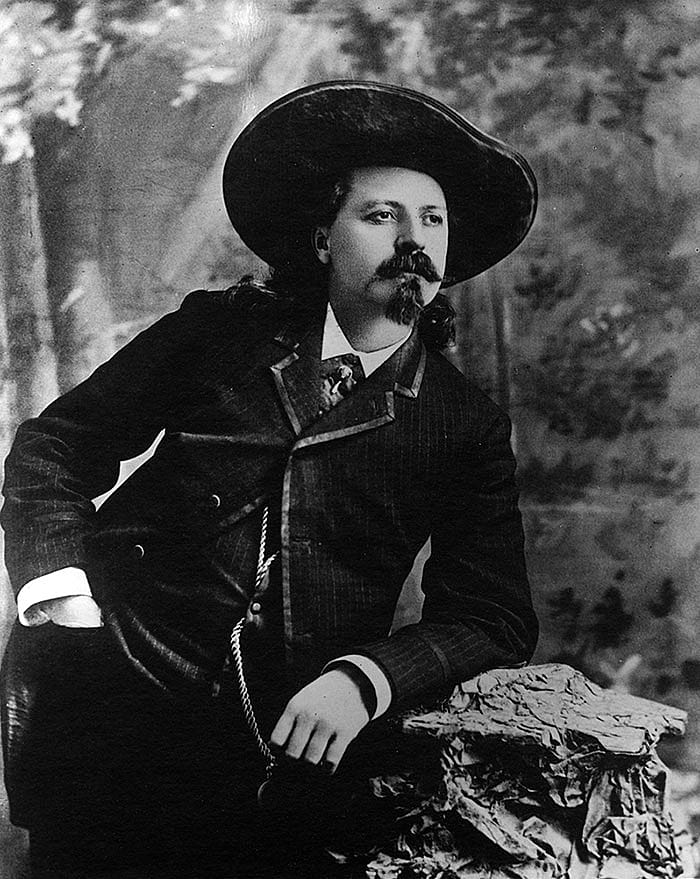

Buffalo Bill was a darned good scout. Recognized by frontier soldiers around the plains as a reliable man to have when danger threatened, Cody was in his twenties when he was made chief scout for the Fifth Cavalry in 1868. In summer 1876, he was designated chief scout of the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, drawing $150 a month for pay, which is approximately $2,500 per month in today’s money. Within a few months, he was paid even more for carrying dispatches through territory still held by Indians. He was young, strong, and at the height of his career. However, at the end of that summer in 1876, Buffalo Bill threw it all away. What could have induced him to turn aside from a sure thing, leave the plains behind, and head in a new direction?

The nation’s centennial year began for Cody much as the previous few years had begun. During the winters since 1872, he had been traveling around the east, portraying himself in a series of border dramas for enthusiastic audiences. During the summers, Buffalo Bill had continued to serve as a civilian scout for the frontier army, gaining a reputation and collecting his share of glory and attention to take back and use to thrill the crowds who would pay, not to see the play, but to see the handsome, magnetic Cody in person. In 1875, however, the army did not need Cody and he was able to spend the summer at home with his wife Louisa and their young family, who were then living in Rochester, New York.

A loving father, Cody treasured his two daughters, Arta and Orra, but he absolutely doted on his only son. Born in 1870 and the youngest child, Kit Carson Cody was named for a scout from an earlier era. As a very young man, Buffalo Bill had once met the original Kit Carson. Impressed with the soft-spoken old Indian fighter, Cody named his son after Carson in the fashion of the time. By 1875, the five-year-old boy could talk and play, and that golden summer was no doubt was filled with laughing children and smiling parents. One can imagine the heavy heart with which Buffalo Bill returned to the thespian life in September, but many of the Combination’s engagements were not far away and he was able to return to visit “Kitty” and his girls regularly.

Winter passed and spring returned in 1876. Buffalo Bill was enjoying success with his Combination, and the troupe played to packed houses in Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and even in Ontario, Canada. They were scheduled to tour eastern cities until July, and the season looked like it would be a lucrative one. On April 21, only days after playing in Rochester and while the actors were busy putting a show together in Springfield, Massachusetts, Louisa Cody telegraphed her husband that their son Kit was seriously ill with scarlet fever. Buffalo Bill finished the first act of the play and then caught the train to Rochester, only to have the joy of his heart silenced by the death of his son in his arms later that night.

“He was to [sic] good for this world. We loved him to [sic] dearly he could not stay, ” Cody wrote to his sister Julia in the early hours of the morning. “And now his place is vacant and can never be filled, for he has gone to be a beautiful Angel in that better world, where he will wait for us. ” The grieving father wrote as he watched over his two daughters, also sick with the same fever and while Louisa slept, overcome with grief and exhaustion from nursing her three children. Kit’s death was a blow to Cody, but he returned to the stage immediately after his child’s funeral.[1]

Buffalo Bill’s heart was no longer with his theatrical career. He ended the season earlier than anticipated, disbanded the company, and answered the army’s call. The summer of 1876 was winding up to be one of the most hotly fought of the Indian Wars, and Cody’s old friends in the Fifth Cavalry needed his expert help. Crook surely could have used Cody on June 17 in his fight at the Rosebud, but Buffalo Bill had not yet made his way west. Buffalo Bill was warmly welcomed when he finally joined the troops, and one man later wrote about seeing him there for the first time since 1869. “There is very little change in his appearance… except that he looks a little worn, probably caused by his vocation in the East not agreeing with him.”[2]

In early July while out on a scout, news reached the soldiers about the battle at the Little Big Horn River. Each man could imagine in grisly detail the fates of their comrades, many of whom they had fought with and camped with. Some of those who had met their end at the Greasy Grass had entertained their fellows with music, and others by forming “nines,” base-ball being the rage on the frontier at the time. Feelings ran high, and some swore bloody revenge on the Indians who had merely been fighting for their lives and homes in that desperate summer. Evening campfires must have been morose affairs, with boast of who would perform what depredation on any Indians that crossed their path.

Anger was in the air when the Fifth Cavalry engaged the Cheyennes at Hat Creek on July 17. Historians still argue about the particulars of Buffalo Bill’s fight with Yellow Hair, but however it happened, Cody took the man’s scalp, probably amid the cheers of the other soldiers. “No doubt you will read of it in the papers,” he wrote to his wife later, in a letter that bragged of the incident.[3] The newspapers did indeed trumpet the deed, and for years afterward Cody himself told different versions of the story to journalists as well as friends. But, what kind of satisfaction could Buffalo Bill honestly have felt as he found himself covered with the blood of someone who was simply defending his home, his family, and his way of life? Later in life, Cody expressed regret at his act, and occasionally denied that it ever happened. But in the furious summer of 1876, he evidenced no remorse.

Only a few weeks after the battle at Warbonnet Creek, word reached Cody of the unfortunate death of his friend and former scouting pard, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. Wild Bill was only thirty-nine years old and had been recently married when Jack McCall shot him in the back on that hot August night. Friends since Cody’s youth, the two men had scouted together, hunted together, and acted together on the stage and the news must have hit Buffalo Bill hard. Citing the reason as the campaign against the Indians being over, Cody quit his position as chief of scouts for the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition. Despite being wounded soon after, he continued to accept difficult and dangerous assignments for a few weeks. In September, Buffalo Bill finally walked away from his scouting career for good.

Cody himself later claimed that he quit the army for the more lucrative acting profession. He never gave any other explanation for taking up a less violent life than to pursue a career on the stage. Buffalo Bill hoped to eventually make enough money to be able to retire from the traveling life and become a cattle baron at his ranch in North Platte near Fort McPherson, Nebraska. There, he could rest on the laurels of his scouting career as well as on his theatrical fame, and enjoy his family and children. Did Cody look back on the events of 1876 with sorrow, regret and a resolve to make a new start? We can only guess, but a series of events such as Buffalo Bill experienced in a few short months would have been enough to break any man’s heart. He never forgot Kitty, Wild Bill, or any of his friends, but the world was watching, and the show must go on.

Notes:

1. Letter from William F. Cody to Julia Cody, April 22, 1876. MS 6 William F. Cody Collection, Series I:B Box 1 folder 5. Spelling has been retained from the original.

2. Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 220.

3. Letter from William F. Cody to Louisa Cody, July 18, 1876. MS 6 William F. Cody Collection, Series I:B Box 1 folder 5.

Post 174

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.