The Cody Art Colony – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2003

Working with Camera, Canvas, and Brush: The Cody Art Colony

By Julie Coleman

Former Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

“An artist cannot catch the spirit of the West unless he actually stays, lives in the West; becomes in fact a part of it.”[1]

Mary Jester Allen, niece of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, espoused this view concerning the importance of place. Taking such advice to heart, painter Edward Grigware and photographer Stanley Kershaw moved from Chicago to Cody, Wyoming, in 1936. Beyond merely relocating, they had a particular goal in mind: to help establish an artists’ colony. They reasoned that with an artists’ colony, Cody would quickly become a leading center of western American art.

Founding an art colony was not an unusual concept. In fact, art colonies had sprung up throughout the United States in the early 1900s, especially in the Midwest and along the East Coast. Many of the artists who identified themselves with the colonies lived in urban areas. They found inspiration in the rural settings of the art colonies where they could work on a regular basis in the company of other creative people. Colonies, and their members, often brought public interest and recognition to the area in which they resided. The Taos Society of Artists, for example, made Taos, New Mexico, nationally famous as an art colony.[2]

The initial idea of developing an artists’ colony in Cody appears to have been the vision of Mary Jester Allen. A driven, ambitious lady, Allen has been instrumental in the founding of the Buffalo Bill Museum in 1927. As an active and informed member of society, along with her passion for art, Allen was well aware of art colonies and their significance. She was the prime candidate to spearhead the project. In a January 2, 1936, letter to Juliana Force, then director of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, Allen voiced her plans to establish an art institute and an artists’ colony. Six artists would be invited to move to Cody, set up their own home studios, and “do their work in their own way in their own setting.”[3]

Grigware and Kershaw were the first artists associated with Cody’s art colony. Both had successful careers in their respective fields of painting and photography. In June of 1936, the artists were officially introduced to the Cody public when the men and their wives were in town for several weeks while their paintings and photographs were on display at the Molesworth furniture store. During their stay, the Cody Enterprise featured several articles on the guests, who were touted as “two of the nation’s most prominent artists.”[4] By the end of July, news circulated about Grigware’s plans to relocate to Cody. In December, the first tangible step in the development of Cody’s art colony occurred when Grigware and Kershaw built two log studio homes on the rim of Shoshone Canyon near Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s statue of Buffalo Bill. Unlike many artists who often only summered at the art colonies, Grigware and Kershaw made Cody their permanent home, a move no doubt encouraged by Allen, who believed that it was vital for the artists to live in Cody. Once settled, it was hoped that the artists’ presence would provide encouragement, hospitality, stability, and continuity for the young, aspiring colony.

The exact circumstances surrounding Grigware and Kershaw’s invitation to join the art colony are not entirely clear. The artists did know people living in Cody with connections to Chicago, such as craftsman and designer Thomas Molesworth and businessman James Calvin “Kid” Nichols. It is probable that communications about the art colony took place with these individuals, the artists, and Mary Jester Allen. According to Nichols’ daughter, historians Lucille Nichols Patrick, her father’s glowing accounts of the country” prompted Grigware to move from Chicago to Cody.[5] Grigware had joined Nichols on a pack trip through the wilderness of the Thorofare country west of Cody in order to pint the country. He was an established painter of landscapes who had received numerous awards and recognition both in the United States and in Europe. The beauty of the land undoubtedly played a role in his decision to relocate.

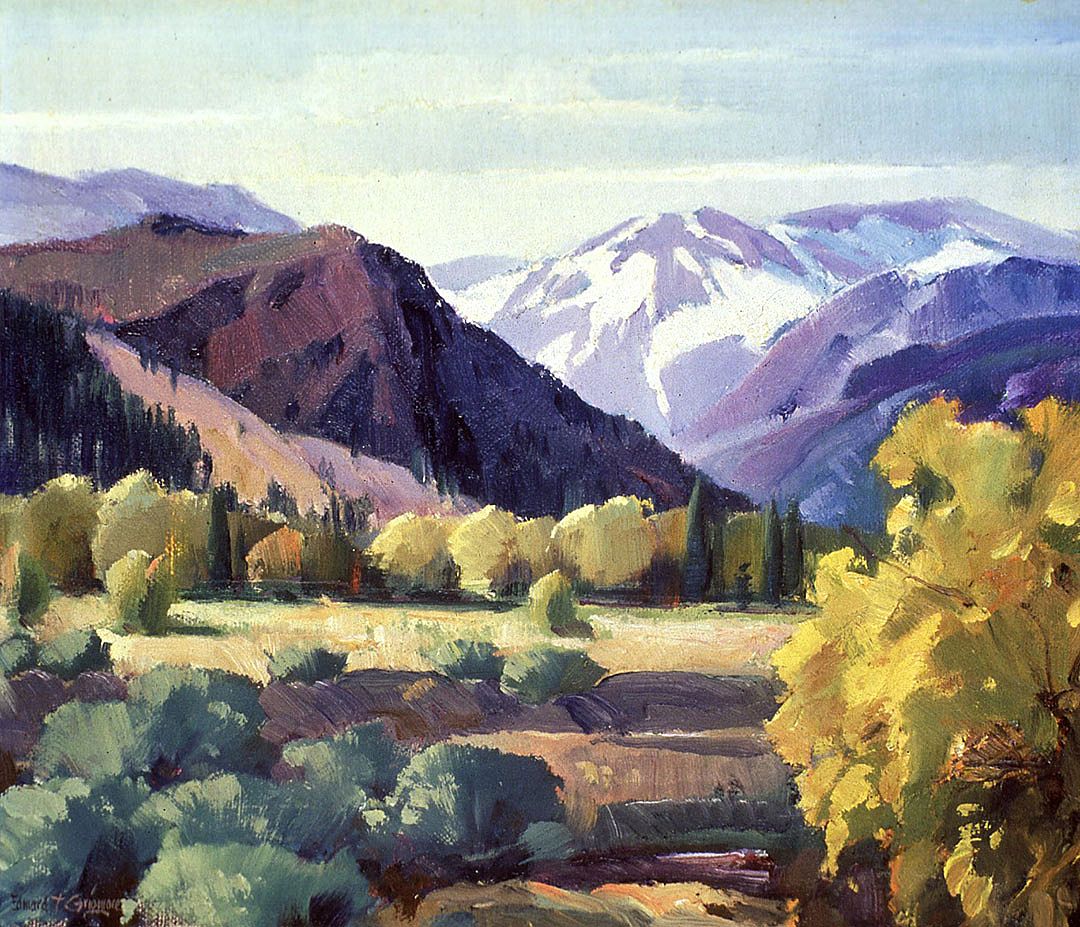

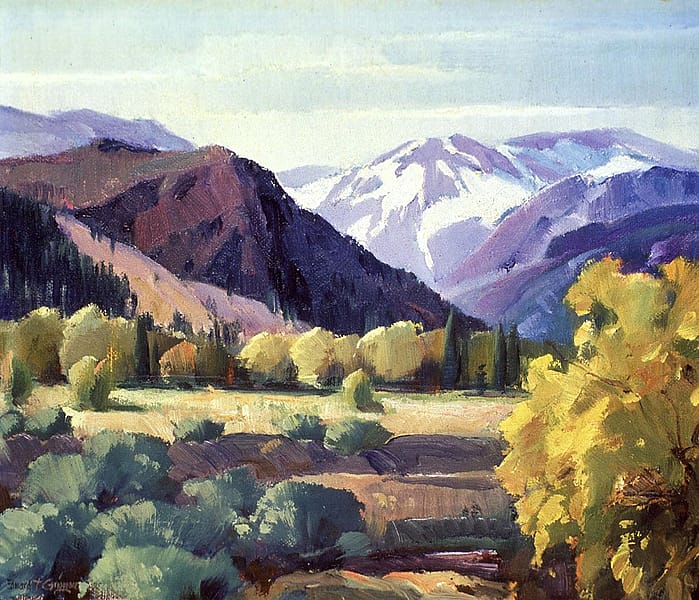

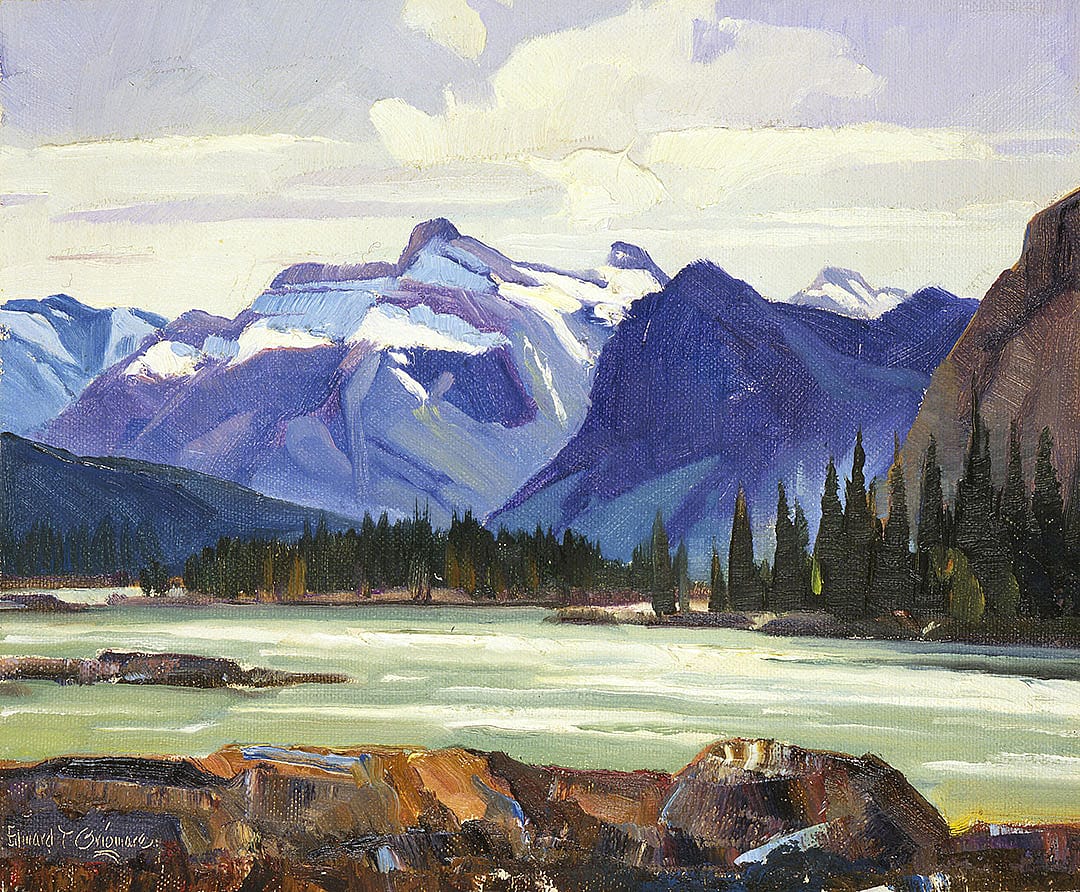

Although at first skeptical about an artist’s chances of making a living in Cody, Grigware soon grew to love both the country and the people. “I’ve painted all through the East. In Canada and Florida, I’ve painted all over. There are prettier countries than this (Wyoming). But here you find a beauty of a majestic nature. It is the beauty you see in an old face that has lived. It makes other countries seem sort of sweet and trivial to me.”[6] His admiration for the country was most evident in his work, which soon took on a western flair. Critics of the time found his rich colors, broad brush strokes, and simplified forms refreshing, and his quickness of brush full of vigor. The recent emergence of modern art, of which Grigware was not a strong advocate, and Cody’s relative isolation from the rest of the art world, may have been other contributing factors to his decision to move west. “I love this big country,” he said, “I’ve gotten away from the ists and isms—the artificial. Here one can find peace of soul, and you can think things out for yourself.”[7] He enjoyed the challenge of the wide, open country and the sharp colors it displayed. His western landscapes, such as Wyoming, are crisp and vibrant. They convey enthusiasm and evoke the serenity of which he spoke.

In addition to easel painting, Grigware received numerous commissions from around the state and country for murals in public spaces. In Cody, he is probably best known for his murals depicting Mormon history in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Grigware was also a friend of Thomas Molesworth, and the two men often collaborated on designs, dioramas, and roomscapes. Appointed a Naval painter in 1935, Grigware was called to do war record painting during World War II. After the war, Grigware returned to Cody where he continued to be an active and involved artist and community member until his death on January 9, 1960.

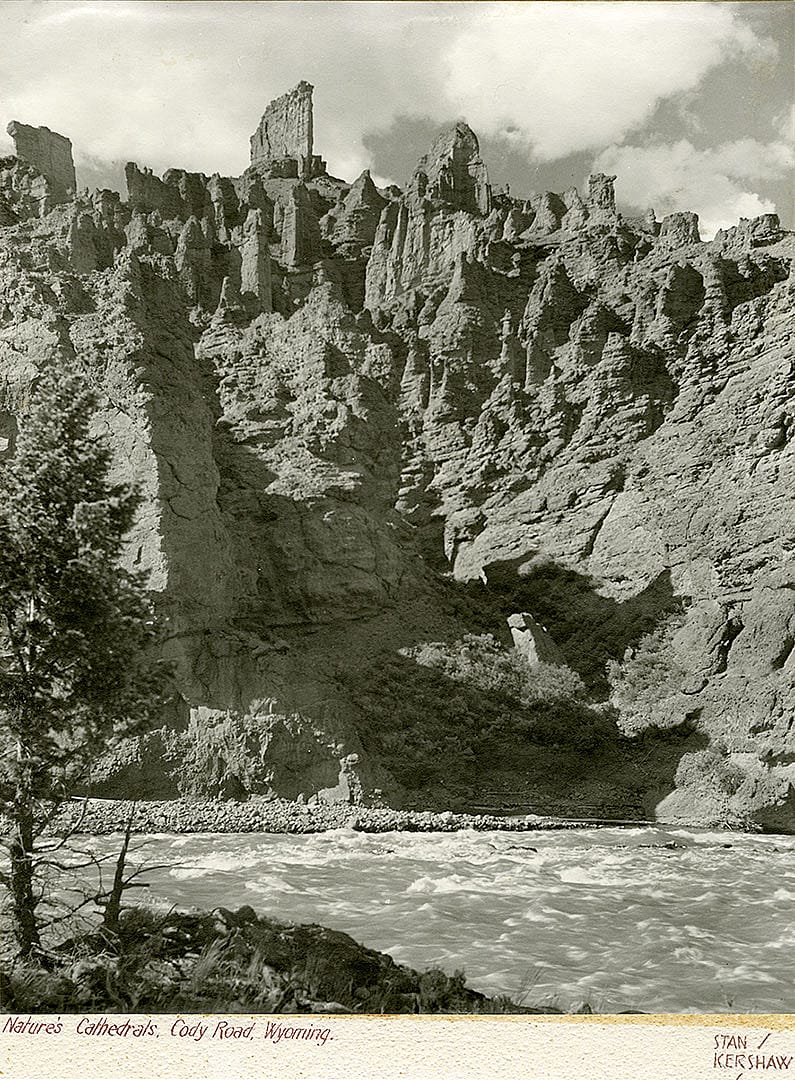

Kershaw, a distinguished photographer, specialized in landscape and cloud effects. He worked mainly with black and white photography but also experimented with color. Many of his images were taken along Wyoming roads, as noted in his titles. In his black and white prints, such as Nature’s Cathedrals, Cody Road, Wyoming, Kershaw utilized line and shape in his compositions and created drama through shadow and light. Most importantly, his images give a sense of the land; it is barren, rugged, and, to those unfamiliar with the area, foreign in its forms. The diverse palette Kershaw employed in his color prints appears exaggerated at first but in reality is comparable to the natural colors of Cody’s western landscape. Kershaw was also a precise recorder of his process when capturing images on film, at times even noting the aperture and time of exposure on the verso of printed photographs.

While Grigware entered his paintings in national exhibitions, Kershaw’s work appeared in the scenic color series distributed by the Standard Oil Company of California; on the cover of National History Magazine; in magazines such as Holiday and Vogue; on the Wyoming highway map; and in Union Pacific Railroad literature advertising the West. Several of his photomurals were also on view in Cody’s Coe Hospital. In addition, Kershaw produced commercial photography for Sunlight and Valley ranches in Cody and the Eaton Ranch near Sheridan, Wyoming. During World War II, Kershaw worked for the National Safety Council and the War Department doing administrative work. He returned to Cody in 1946 and built a home on the Northfork. He died in Floarida in July 1963.

Grigware and Kershaw, working with camera, canvas, and brush, recorded the unrivaled scenic beauty and unique historic background of the region. Cody was an ideal setting for inspiration and artistic expression, and by exhibiting their images in, around, and beyond the region, they helped contribute to Cody’s recognition and popularity as a center for western American art.

In addition to helping establish the art colony, the two artists also assisted with other aspects of Allen’s vision. In the summer of 1937, the Cody Summer School of Art opened, a program sponsored by the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association as an addition to the Buffalo Bill Museum. Dubbed the Frontier School of Western Art, the school’s faculty consisted of Elmer Forsberg, a portrait, landscape, and mural painter who offered to teach classes in composition, landscape, and figure painting; Grigware, who taught drawing and painting; and Oscar Havisson, who provided instruction on sculpture. A plan was also announced for a frontier village that would house an art gallery and school, an arts and crafts building, an open-air theater, and an Indian village.

The entire complex would be built near the Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney statue of Buffalo Bill as a scout and would be directed by Kershaw. In addition, four studio homes would be built that summer. However, by 1939, Grigware and Kershaw’s studios were still the only two buildings at the colony. They claimed they were anxious to be joined by other artists, for “the more Cody became an art center, the more work there would be and the greater the need for a variety of talent to draw upon.”[8] Despite their high hopes, the envisioned art colony did not materialize. In a 1939 Cody Enterprise article, it was reasoned that the slow establishment was due in part to the fact that “it takes time for successful artists to decide to break away from business and social connections and move to a new location.”[9] However, their highly selective, slow, and hesitant approach may have contributed to the eventual dissolution of the art colony.

Although the colony did not flourish as intended, artistic opportunities and experiences continued to develop in Cody. By 1940, the Frontier School of Western Art had seen a steady growth in enrollment, and three of its students had gone on to continue their art studies in Chicago: Betty Phelps, Cherry Sue Orr, and Jess Frost. With World War II on the horizon, a large enrollment was not expected for 1941. The number of students from eastern states, however, increased. Obviously, word about Cody as a viable center for art was spreading. But in that same year, Grigware and Kershaw were called to service in the war effort. In their absence, the school foundered and eventually disbanded.

Grigware and Kershaw came to Cody to be inspired and to interpret the land and people around them. Although an official, organized art colony may not have come to fruition, they influenced another generation of artists, such as internationally acclaimed sculptor and painter Harry Jackson, and helped create the artistic community that is still very much in existence today. Together, highly trained and skilled artisans and craftspeople, local art galleries, organizations such as the Cody Country Art League and the Whitney Western Art Museum, and events like the Buffalo Bill Art Show & Sale continue to make Cody, as these early leaders envisioned, a leading center of western American art.

Notes:

1. Mary Jester Allen to Juliana Force, 2 January 1936, Whitney Museum Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, microfilm reel N588.

2. Six painters established the Taos Society of Artists in July 1915 to expose and sell their work through traveling exhibitions. They were later joined by fifteen other members. Success of the society was immediate, bringing critical recognition for the artist and the town of Taos. See Robert R. White, ed., The Taos Society of Artists (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press in cooperation with the Historical Society of New Mexico, 1983).

3. Allen to Force, 2 January 1936, Whitney Museum Papers.

4. “Chicago Artists Display Pictures Here,” Cody Enterprise, June 24, 1936; “Chicago Artist Plans Building at Museum,” Cody Enterprise, July 29, 1936.

5. Lucille Nichols Patrick, The Candy Kid: James Calvin “Kid” Nichols, 1883–1962 (Cheyenne, Wyoming: Flintlock Publishing Company, 1969), p. 139.

6. Mike Leon, editor and publisher, “Ed Grigware’s Art,” Wyoming, The Feature and Discussion Magazine of the Equality State, Vol. I, No. 5 (1957), pp. 14–19.

7. “Edward Thomas Grigware: 1889–1960,” Cody Enterprise, February 22, 1939.

9. Ibid.

Post 175

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.