How the West was Written – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2001

How the West was Written

By Nathan Bender

Former Curator, McCracken Research Library

Writing was an integral part of personal life even in the frontier west. It permitted the keeping of diaries, long distance correspondence and business, and the formal printing of laws, books and newspapers. Despite the stereotype of illiterate frontiersmen and cowboys, reading and writing were essential to the successful exploration and settlement of the west. Western printing presses developed right along with the establishment of towns, reliable transportation and mail delivery. Creative writing was present from the beginning, and poetry was a popular literature. This overview looks at the history of western writing and publishing as seen from the northern Rocky Mountains and northern Great Plains.

Writing with Pictures

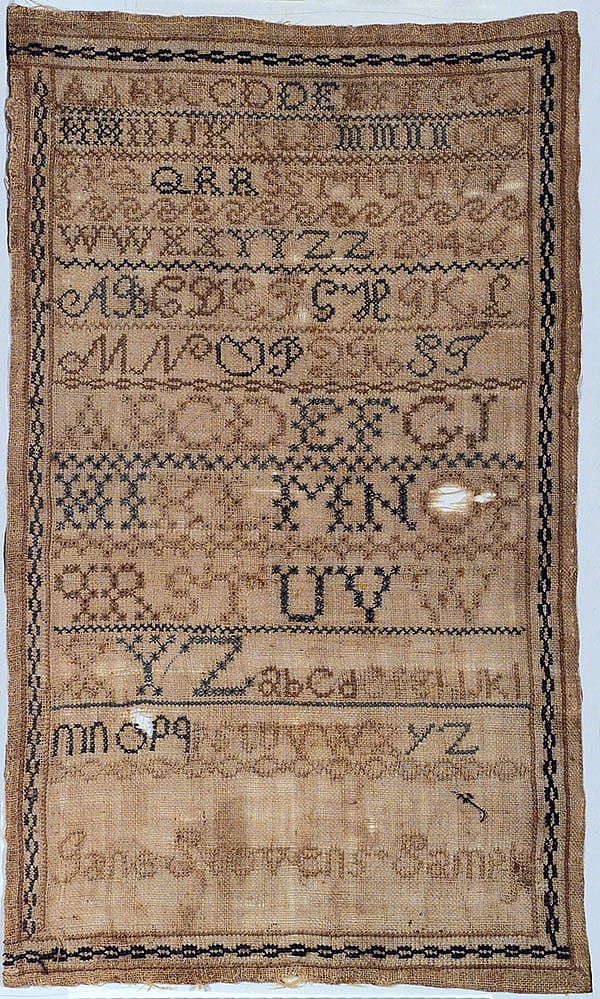

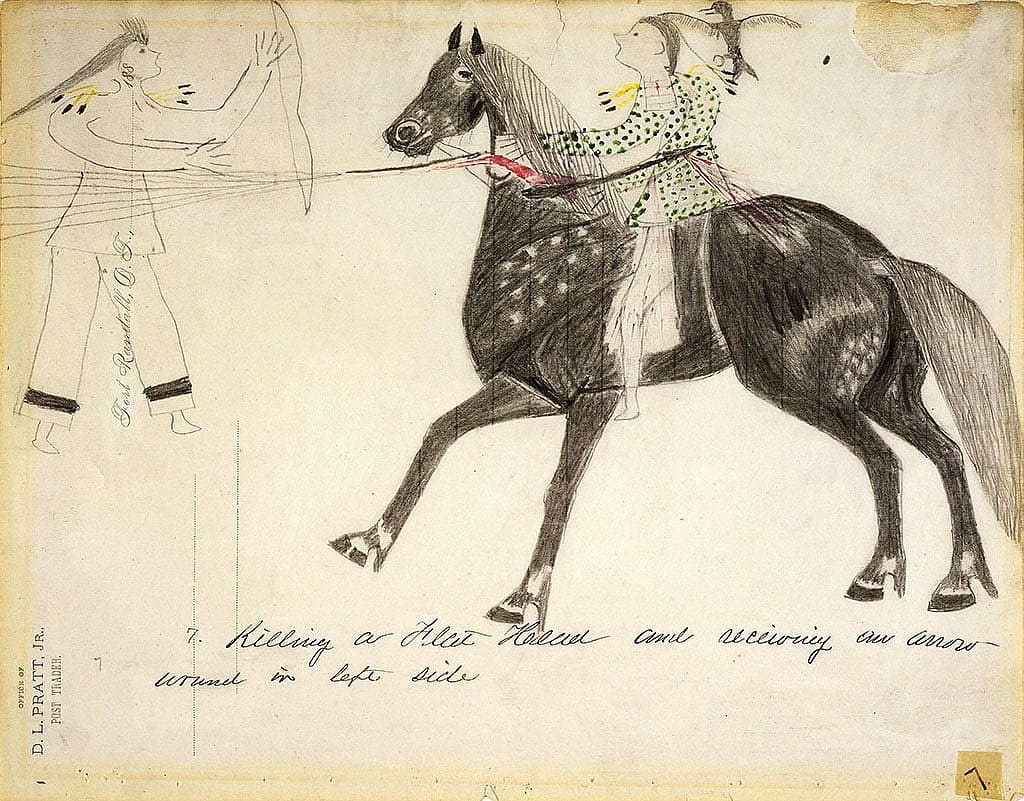

Artistic renderings of deeds and visions served as a traditional writing style for the Plains Indians. Petroglyphs carved into stone, pictographs painted onto hide, and pencil drawings sketched into ledger books are all part of a long tradition of recording meaningful events with representational drawings.

Obviously, not all drawings were intended as “writing,” but painted robes known as “winter counts” that depict annual events in a person’s life, and ledger drawings that depict historical events are able to be “read” by those skilled in their interpretation. Thus, these drawings represented events rather than particular words. Much of the historic ledger book art documents personal deeds of war or of the hunt.

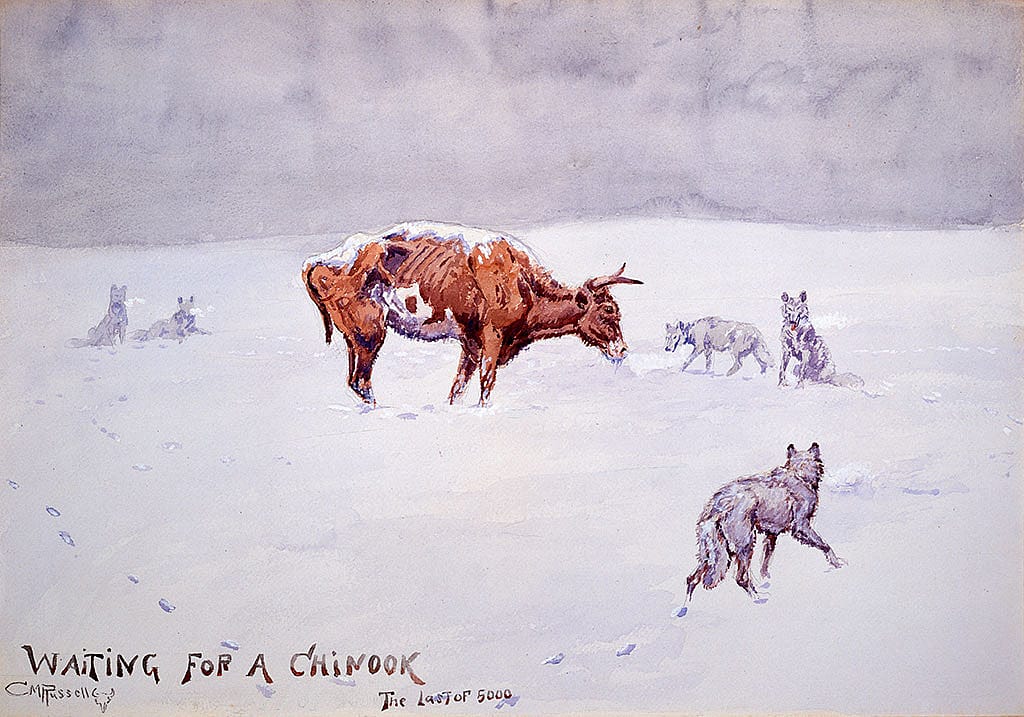

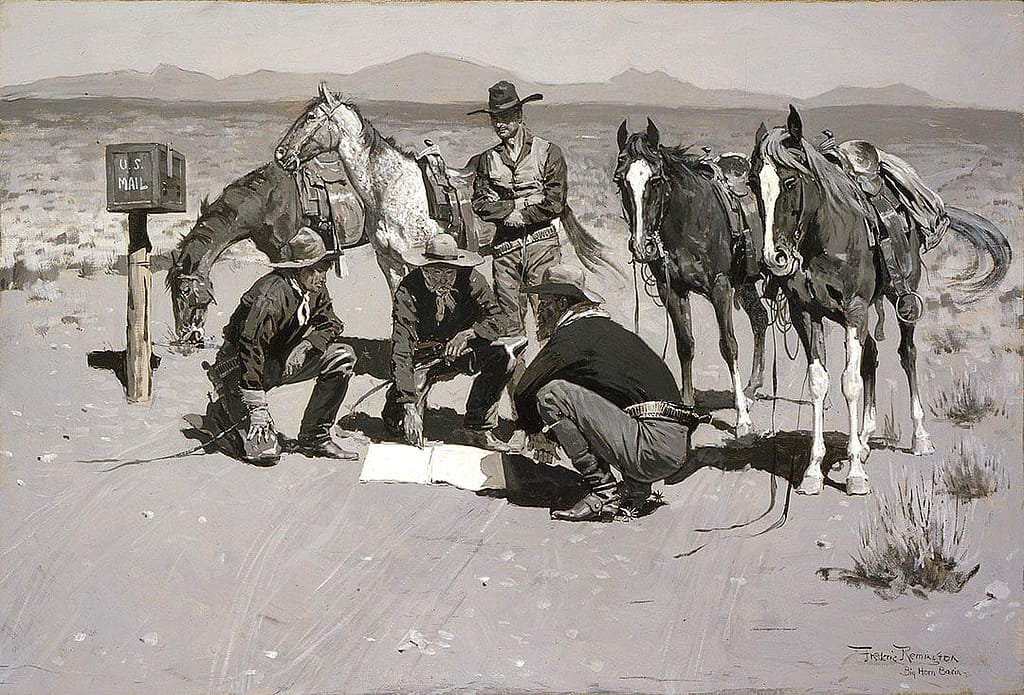

The concept, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” can also be found in Euro-American traditions. Cowboy artist Charlie Russell, when requested by non-resident owners for a report on a herd of 5000 cattle after the deadly winter of 1886–1887 simply drew a starving steer that he titled Waiting for a Chinook. His drawing conveyed the disastrous conditions far more eloquently than any written report.

Cattle brands are also an ancient tradition that were commonly used for western ranching, but are very different from Plains Indian pictographs. Brands are distinctive marks to identify ownership. They have their own rules of literacy, being an odd amalgamation of alpha-numeric characters and pictographic symbols. Public registration regulates their use and prevents confusion that would arise from the same brand being used by different ranches.

Languages and the Written Word

The English language became the dominant language of the West, though Spanish, French, German, Chinese, Swedish and many other languages were present due to America’s colonial history and continuing immigration. Writing in all of these languages was common, and so it is not unusual in western historical archives to find instances of letters or books printed in non-English languages that date from the nineteenth or early twentieth century. The English language was commonly learned by second-generation American children, but that did not preclude bilingual ethnic communities from prospering, especially with the already well-established Spanish language in California and the southwest.

As communication between Indians and non-Indians developed and people took to learning one another’s languages, the need arose for a text written version of the Indian languages. If one looks at the history of printing in the United States, it is soon apparent that among the earliest printings of each state are books published in American Indian languages. These vary greatly from simple though inexact attempts to use European language alphabets to sound out American Indian words, to very sophisticated syllabaries which assign unique characters to individual syllables. Early publications in American Indian languages include word lists for conducting commerce and translations of the Bible and other religious writings for the teachings of Christianity.

Missionaries such as James Evans, Stephen R. Riggs, and Rodolphe Petter devoted their lives to learning Indian languages as a means of spreading the gospel. The creation of word-based writing systems and the consequent production of dictionaries and translations were enormously valuable scholarly undertakings. Their achievements allowed native speakers to read and write in their own languages. A few American Indian nations created their own formal writing systems after understanding the concept as practiced by Euro-Americans. Sequoyah is deservedly famous for developing the Cherokee syllabary in Georgia, but further west in Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska, the Sac and Fox (Meskwaki) also developed their own syllabary, that in turn was adopted by the Kickapoo.

At the end of the frontier era, forced reservation culture and government boarding schools often discouraged or even prevented native language use. Bilingual language programs for American Indians have been supported by the federal government since the early 1970s, though not soon enough to save many of the languages.

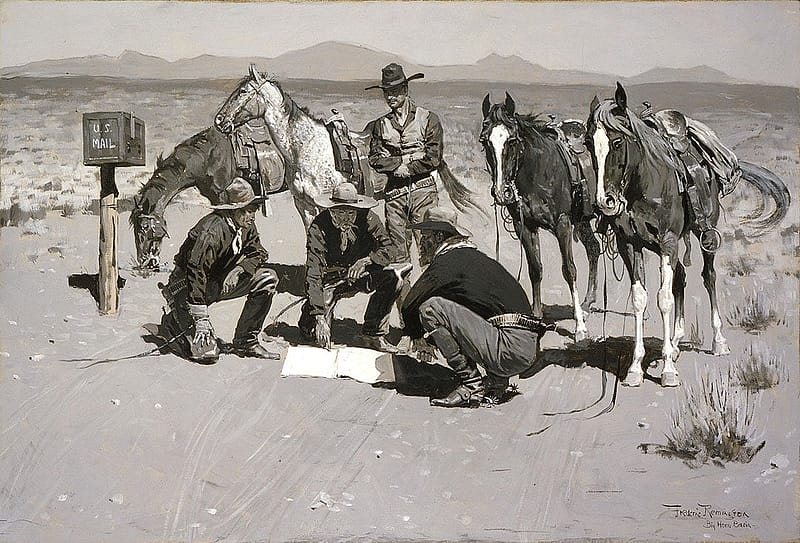

Mail Delivery and the Pony Express

Delivery of private correspondence, business papers and newspapers in the west depended upon reliable and trustworthy transportation. After California was admitted to the union in 1850 a need arose for communication between east and west coasts. Steam ship routes up the Missouri and its tributaries were confined by the Rocky Mountains, and sailing by sea around South America was a long and dangerous voyage. A cross-country land route promised shorter distances and faster delivery time. Overland mail and passenger services by stagecoach were established in the mid-1850s by the freighting firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell and by their rivals, the Overland Mail Company. To increase the speed of delivery, Russell, Majors & Waddell set up a chain of Pony Express relay stations with fast horses and teenage riders, armed with small bibles and Colt revolvers, that stretched from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California, beginning on April 3, 1860. This express mail service succeeded in delivering mail over a distance of 2,000 miles in only 10 days. William F. Cody later highlighted the excitement and adventure of the mail delivery in re-enactments for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

In early 1861 Wells, Fargo & Company and its Overland Mail Company obtained a government contract to continue the Pony Express and stage mail services. However, in October 1861 the Pony Express service was ended with the opening of the final connecting link of telegraph lines between California and Missouri, an electronic mail service that could send messages at nearly the speed of light. The delivery of regular mail was further improved with the building of railroads from the east and west, which joined to form a transcontinental railway in 1869 in Utah at Promontory Point. By the 1870s eastern periodical publications were becoming regularly available in the west. Horses and coaches continued to be used for mail delivery in areas without railways until replaced by automobiles on improved roads.

Early Printing in Wyoming and Montana

The 1860s saw several printing presses and newspapers established in the northern Rocky Mountain territories. At Fort Bridger, Utah Territory (now Wyoming), a small single page newsletter the Daily Telegraph was printed in 1863 by Hiram Brundage. This paper, known from only a single issue, published news reports obtained from telegraph dispatches. In 1864 John Buchanan started the Montana Post that published local and national news in the gold mining camp of Virginia City. The Frontier Index was published by Legh and Fred Freeman from a railroad car that traveled the rails serving railroad construction crews. The Freemans began their paper in 1865 in Nebraska and by 1868 had worked their way across Wyoming.

Montana Territory’s first book was The Vigilantes of Montana by Thomas J. Dimsdale. This title, published in 1866 in Virginia City by the Montana Post Press, became world famous for its exciting and detailed accounts of life in the gold fields and remains one of the most important western titles ever printed. Wyoming’s first book was published at Fort Laramie that same year, when it was still Dakota Territory, being fifty copies of Dictionary of the Sioux Language by Lieuts. Joseph Hyer and William Starring, with compilation aided by Lakota language interpreter Charles Guerreu. The second book was a reprinted edition published by the Freeman brothers’ railroad car press at Green River City, being A Vocabulary of the Snake, or, Sho-sho-nay Dialect by Joseph A. Gebow, in 1868.

Early printing on the western frontier strongly correlates with the establishment of early population centers, such as mining camps, army forts, or railroad towns. Within the 1870s and 1880s most towns of any size were setting up newspapers, and local and state governments were relying on the presses for the publication of their laws. Newspaper editors were not known for timidity, and they made no apologies for trying to influence public opinion. Newspapers were usually a strong asset to a new town, as a good paper could provide a community with a sense of its own identity, promote the town and keep it informed of current events. The establishment of local presses and papers combined with telegraph service, reliable postal delivery, and an east-west railroad connection were a powerful combination that enabled fledgling towns to quickly grow and do business with the rest of America.

Western Poetry

Poetry was quite popular in the nineteenth century. In the gold mining camp of Virginia City in 1864, miners had access to a bookstore with the latest Victorian novels and poetry. The Montana Post routinely printed poetry, both reprinted and original from the miners themselves. The very first issue of August 27, 1864, begins with “The Haunted Palace” by Edgar Allan Poe, which qualifies as the first published poem in the state. The paper’s second issue of September 3 published the first original poem, “The Dying Son—in Montana,” by R.D. Aye. Composed of seven morbid stanzas, it begins:

I am dying, mother, dying, Quoth the feeble, fainting boy, Without thy tender care to sooth Me in this agonizing hour.

Other original poems published by the Post in the next year included verse that was humorous, lovesick, patriotic (the Civil War was going full tilt), and philosophical. New lyrics were presented for popular tunes and a requiem was printed for the death of President Lincoln. All in all it is apparent that the miners were actively engaged in creative writing—especially during the winter months when mining was at its low ebb.

One notable and early western poet was John W. “Captain Jack” Crawford (1847–1917), who had scouted with William F. Cody for the 5th Cavalry in 1876, and then joined with Cody as a member of the 1876–1877 Buffalo Bill Combination theatrical troupe. A native of Ireland, Crawford grew up in Pennsylvania, heading for the Black Hills in the early 1870s where he worked as newspaper reporter, gold miner and U.S. Army scout. A prolific poet and able showman, he published his first book of poetry in 1879 in San Francisco, titled The Poet Scout: Verses and Songs. In 1886, in his second book, The Poet Scout: A Book of Song and Story, he included a poem about Buffalo Bill that he had written August 24, 1876, the day Cody left his position as Chief of Scouts for Gen. Crook’s 5th Cavalry to return east. The first stanza of “Farewell to our Chief” reads:

Farewell! The boys will miss you, Bill; In haste let me express The deep regret we all must feel Since you have left our mess. While down the Yellowstone you glide, Old Pard, you’ll find it true, That there are thousands in the field Whose hearts beat warm for you.

Crawford went on to write several more books of poetry, including some of the earliest known cowboy poems. It is interesting that he also used his verse to promote social causes, and his lifelong interest in mining led to his poem, “Only a Miner Killed,” from his The Poet Scout (1886: p. 74–75). The last verse of this poem reads:

Only a miner killed! Bury him quick, Just write his name on a piece of a stick. No matter how humble Or plain the grave, Beyond all are equal—The master and slave.

Post 177

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.