The Black-Footed Ferret – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2000

Here, Gone, and Back Again: The Black-Footed Ferret

Deborah Deibler Steele

Former Curatorial Assistant, Draper Natural History Museum

Ed. Note, 12.01.2017: Black-footed ferrets and their recovery have been in the news again recently, and even the subject of a documentary, Ferret Town, produced by The Content Lab LLC, with support from the Meeteetse Museum Foundation, the Wyoming Humanities Council, and the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, and with the cooperation of the US Fish & Wildlife Service, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and private landowners. The Center of the West hosted a preview of the documentary in September 2017.

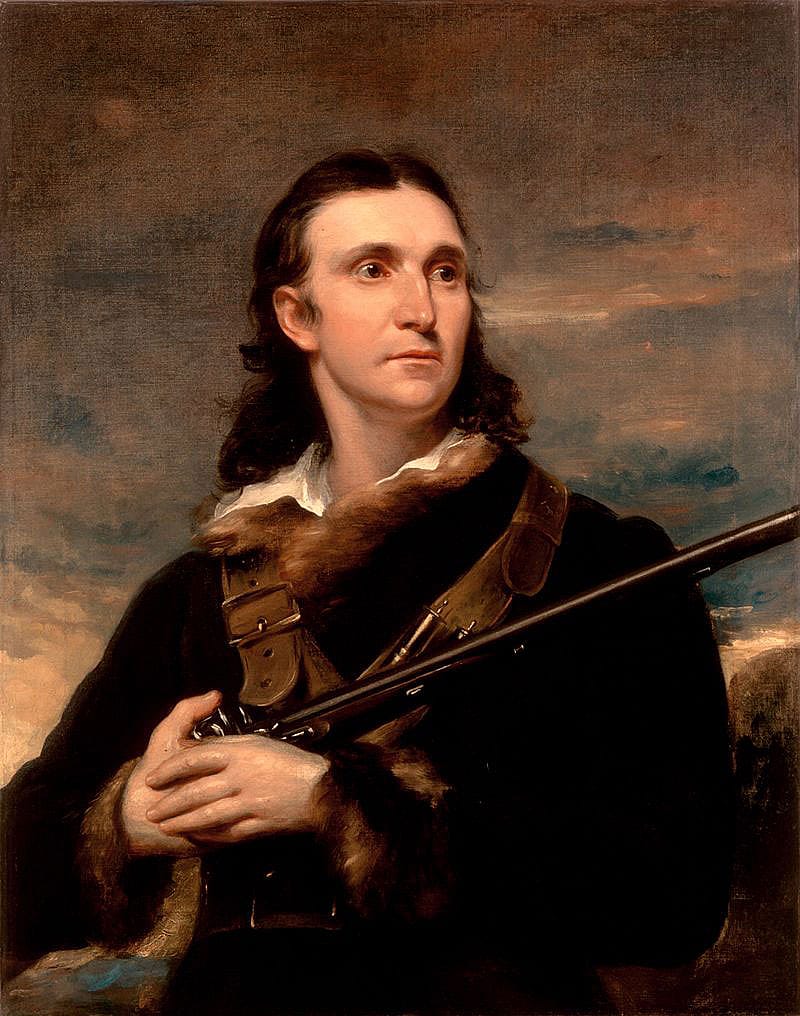

It is with great pleasure that we introduce this handsome new species. —John James Audubon and John Bachman, 1851

John James Audubon and John Bachman published the first scientific description of the black-footed ferret in 1851 in Quadrupeds of North America. Although Audubon’s 1843 expedition collected 23 species of mammals, none were new to science, and none were ferrets. Audubon and Bachman based their description and illustration of the black-footed ferret on a skin forwarded to them by fur trader Alexander Culbertson from the “lower waters of the Platte River” near Fort Laramie, Wyoming.

Apparently, Audubon’s specimen was lost or destroyed because other naturalists questioned whether the animal actually existed. This tarnished Audubon’s reputation. According to Elliott Coues, “Doubt has been cast upon the existence of such an animal, and the describer has even been suspected of inventing it to embellish his work.” Coues vindicated Audubon when he published his 1877 confirmation of the species based on several well-documented specimens.

Audubon did not have the opportunity to observe living black-footed ferrets. He assumed they behaved like European ferrets: “It feeds on birds, small reptiles and animals, eggs, and various insects and is a bold and cunning foe to the rabbits, hares, grouse, and other game of our western regions.” Audubon was wrong and the illustration in Quadrupeds reflects this error, showing a black-footed ferret above ground, raiding a nest of eggs. In reality, black-footed ferrets are extremely specialized predators who live in prairie dog burrows and eat almost nothing but prairie dogs.

The black-footed ferret is a member of the weasel family (Mustelidae), which includes the skunk, badger, fisher, marten, otter, mink, wolverine, and weasel. Black-footed ferrets have a long,g thin body, short legs, and a very flexible spine, allowing them to run through small tunnels and turn in tight spaces. These adaptations allow them to live underground in prairie dog colonies where the temperature is more uniform than on the surface, it is easier to conserve water, and they are protected from surface predators with a taste for ferrets. Potential predators include badgers, coyotes, bobcats, golden eagles, great-horned owls, ferruginous hawks and domestic dogs. Black-footed ferrets are strong and limber, allowing them to catch and kill prey larger than themselves. Adults are 18 to 22 inches long and weigh between one and two-and-a-half pounds. Ferrets live alone except during breeding season. The kits are born in May or June, usually in litters of three or four.

Black-footed ferrets are the only ferrets native to North America. They have lived in North America for at least 30,000 years and have lived everywhere that prairie dogs have lived. At one time black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs ranged throughout the Great Plains and intermountain basins of the Rockies, from Canada to Mexico. When Audubon traveled west in 1843, there were as many as five billion prairie dogs in colonies covering millions of acres of grassland. This vast area of prairie dog colonies provided habitat for 500,000 to 1,000,000 ferrets (Anderson, 1986).

Although Audubon and Bachman were the first to describe black-footed ferrets for science, the ferrets were known to others long before 1851. Black-footed ferret bones have been found in Paleo-Indian archeological sites dating back 10,000 years. Plains Indians used black-footed ferret skins for medicine pouches, headdresses and sacred objects. Juan de Oñate reported seeing ferrets in what is now the southwestern U. S. in 1599. The American Fur Company listed 86 black-footed ferret pelts in their records from 1835–1839 (Anderson, et al., 1986).

As settlers moved west, large areas of the Great Plains were converted to farm- and ranch-land. Prairie dogs were (and often still are) viewed as pests competing with livestock for forage. In 1902, the director of the U.S. Biological Survey, C. H. Merriam, estimated that prairie dogs reduce the productivity of land by 50–75 percent. Unfortunately, he did not base his estimate on scientific data. Although forage is shorter on prairie dog colonies, current research shows the nutrients, digestibility and productivity are enhanced (Miller, et al., 1996).

Beginning in the late 1800s, individual landowners poisoned prairie dogs with strychnine and other agents. Between 1915 and 1939, the U.S. Biological Survey poisoned millions of prairie dogs. The Animal Damage Control Act of 1931 authorized eradication programs still in place. These prairie dog eradication programs, diseases, recreational shooting, habitat fragmentation and habitat destruction due to development have drastically reduced their population. They now inhabit only about 1 percent of their previous range (Anderson, et al., 1986, and Miller, et al., 1996). In 1998, conservation organizations began pressuring the federal government to list the black-tailed prairie dog, one of five species of prairie dog, as an endangered species.

The lives of black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs are so closely intertwined that threats to prairie dogs affect black-footed ferrets. As populations of their prey dropped, so did the population of black-footed ferrets. Other animals dependent on prairie dogs, including burrowing owls, mountain plover, ferruginous hawks, swift foxes, and rattlesnakes, also declined across much of their range.

Black-footed ferrets now have the distinction of being one of the rarest animals in North America. By 1964, the federal government was ready to declare the black-footed ferret extinct, but a small population was discovered in South Dakota. When the Endangered Species Act passed in 1966, the black-footed ferret was one of the first animals listed as endangered. Only eleven litters of kits were produced during the ten years that biologists studied the South Dakota ferrets. Finally, the few survivors were captured for an unsuccessful breeding program. When the last captive South Dakota ferret died in 1979, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service again considered declaring black-footed ferrets extinct.

Then in September 1981, a Wyoming ranch dog killed a ferret near Meeteetse! Federal authorities were notified and black-footed ferrets had another chance for survival of the species. Biologists studied ferrets in the field until 1985, when distemper killed most of the wild ferrets. Six ferrets were captured in the fall of 1985. The last survivors were captured in 1987, bringing the captive population to 18 black-footed ferrets. Those 18 animals were all that remained between black-footed ferrets and extinction.

The ferrets were taken to the Sybille Wildlife Research and Conservation Education Center near Wheatland, Wyoming. Although there has been some contention between wildlife biologists and various government agencies about how to manage black-footed ferrets, the captive population reproduced successfully. As the population grew, the ferrets were distributed to zoos in the United States and Canada. By 1991, the breeding program had been successful enough to begin releasing ferrets into the wild in Shirley Basin, Wyoming. Between 1991 and 1994 almost 230 ferrets were released in Shirley Basin. Releases stopped in 1995 when sylvatic plague decimated the prairie dog population. Against the odds, the feisty ferrets survived in Shirley Basin and a few were sighted again in late 1996. Additional populations of ferrets have been established in Montana’s Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge (about 50 surviving animals) and Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, South Dakota’s Badlands National Park (about 200 ferrets), and in Aubrey Valley, Arizona (a few).

Since Audubon’s description in 1851, black-footed ferrets have been reduced from a population of hundreds of thousands to a remnant teetering on the brink of extinction. Their survival depends on preservation of habitat that ferrets, prairie dogs and an entire prairie ecosystem depend upon. Preservation of that habitat depends on human choices and public policy decisions.

Bibliography

Anderson, Elaine, S.C. Forrest, T.W. Clark and L. Richardson. 1986. Paleobiology, biogeography, and systematics of the black-footed ferret, Mustela nigripes (Audubon and Bachman), 1851: in The Black-Footed Ferret, Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs #8, 11–62.

Audubon, J.J. and J. Bachman. 1851–1854. Quadrupeds of North America: 3 vols., V.G. Audubon, New York.

Coues, Elliott. 1877. Fur-Bearing Animals: A Monograph of North American Mustelidae. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Miller, Brian, R.P. Reading, S. Forrest. 1996. Prairie Night: Black-Footed Ferrets and the Recovery of Endangered Species. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., p. 254.

Wyoming Game and Fish Department. 1997. Black-Footed Ferret: Wild Times, v. 13, n. 8.; (online).

Post 182

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.