New Adventures with Birds of Prey – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2012

New Adventures with Birds of Prey

By Charles R. Preston, PhD

Willis McDonald, IV Senior Curator of Natural Science and Founding Curator-in-Charge of the Draper Natural History Museum

National Geographic magazine has played an important role in many a budding explorer’s life and career. It certainly played a big role in mine. Both of my parents were stationed with the U.S. Army at Ft. Chaffee, Arkansas, and I spent a good deal of after-school and summer time doing chores for my grandmother in her old Victorian-style boarding house in nearby Ft. Smith, Arkansas. Western history buffs know Ft. Smith as Judge Isaac Parker’s “Hell on the Border” town. It was made famous in the book and movies True Grit, as the western seat of law and order bordering the wild and wooly Oklahoma Territory in the late nineteenth century.

It still inspired a frontier spirit in me and my childhood friends growing up in Ft. Smith in the 1950s. My particular brand of frontier spirit was directed toward exploring nature and all things wild. So, when I discovered the great cache of National Geographic magazines tucked away in the attic by one of my grandmother’s boarders, I was ecstatic! I felt like I had discovered a magic carpet that would take me to exotic, dangerous, and mysterious places around the world. Despite being explicitly forbidden from climbing up to the dingy, spider-filled attic, I snuck up there at every opportunity with a candle or flashlight to pour through the boxes of National Geographic magazine. In the autumn of my eighth year, I stumbled on an issue that has helped guide my life’s work in wildlife ecology, and especially raptor biology and ecology, ever since.

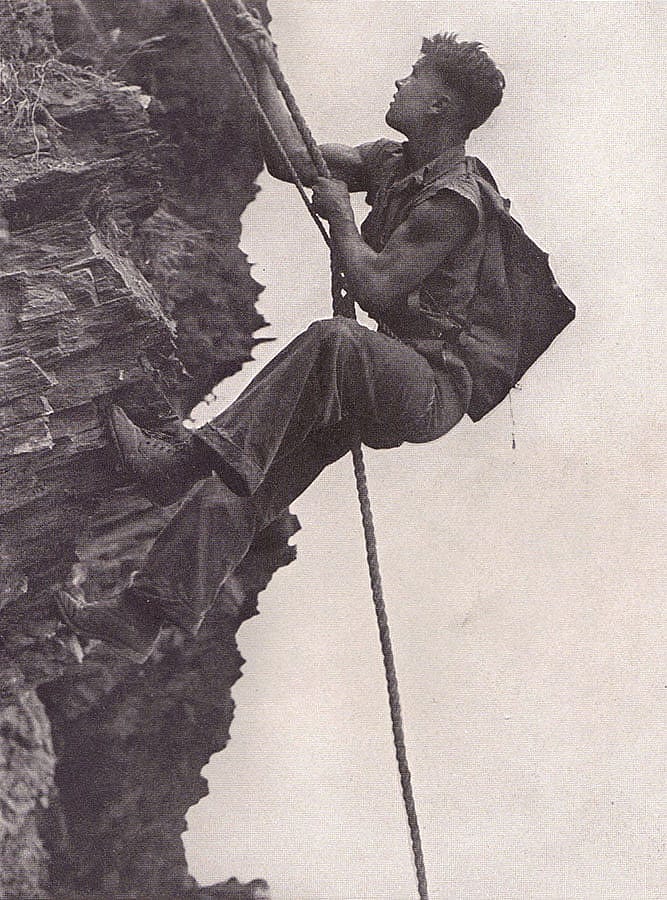

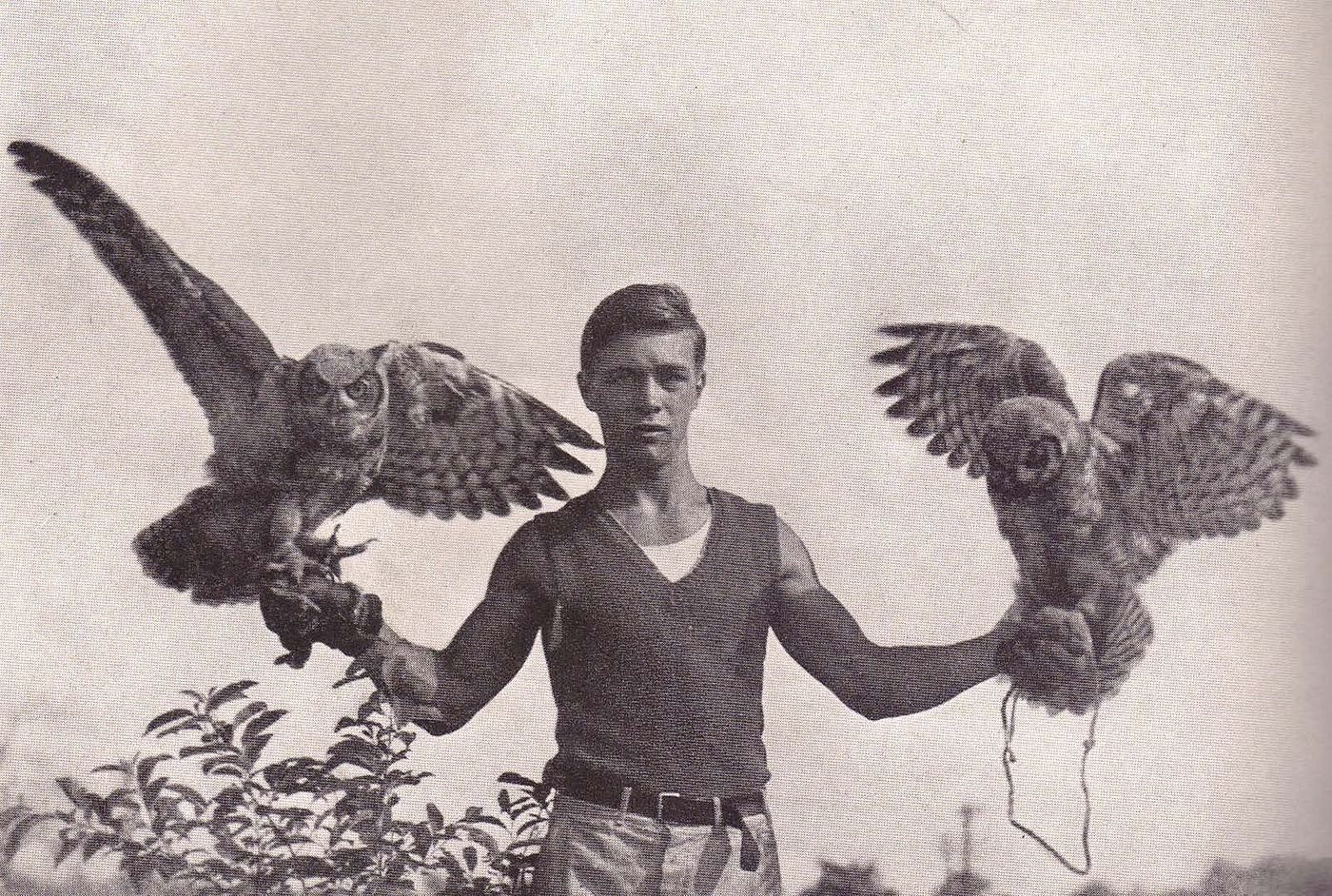

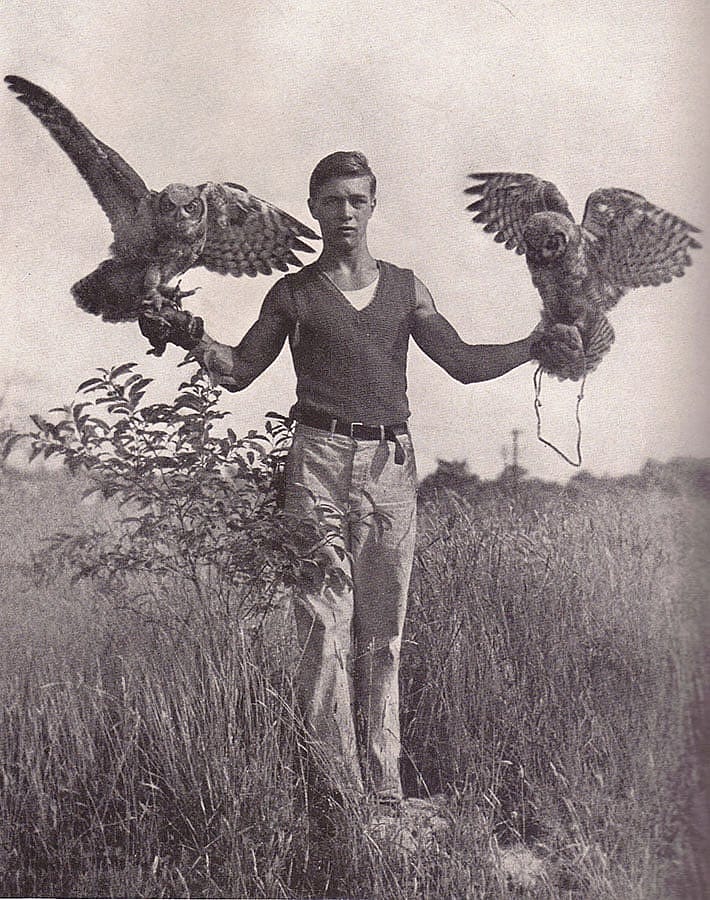

The issue was published in July 1937, and contained an article and series of dramatic black-and-white photographs telling the story of two teenaged twin boys and their friends as they studied, photographed, captured, and trained birds of prey mostly in and around Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. I was especially enthralled with the photographs of powerful birds of prey perched on the boys’ gloved hands. I’d never thought of Washington, D.C. as exotic, but this article opened my eyes to the awe and mystery of nature that surrounds us everywhere. Birds of prey provide the perfect eye-openers. Some youngsters are first lured into a life of science by dinosaurs, faraway planets, or volcanoes, but for me it was those magnificent birds with talons as sharp as needles, flesh-tearing beaks, and huge eyes positioned like ours in the front of the face.

The article was titled “Adventures with Birds of Prey,” and it was authored by the twin teenagers, Frank and John Craighead. This was the Craigheads’ first published article, but not their last by a long shot! These two explorers, scientists, educators, and conservationists became world famous—largely for their pioneering work on eagles and grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone region. We present an overview of the Craigheads’ careers and accomplishments in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s new Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame exhibition and in our recent book An Expedition Guide to the Nature of Yellowstone and the Draper Museum of Natural History.

Of all the places they could have lived, John and Frank Craighead chose to live, work, and study most of their adult lives here in the Greater Yellowstone region. Frank died a few years ago, but John, now in his nineties, resides in Montana. I’ve been lucky enough to explore and conduct research in many of those exotic places I first saw in National Geographic—the Galapagos Islands, Belize, Ecuador, etc. But, like the Craigheads, I chose the Greater Yellowstone region above all others. Although I’ve studied a broad range of species and ecological topics, birds of prey have remained at the forefront of my scientific research program. In addition to being interesting in and of themselves, raptors are especially good barometers of environmental health and good models to explore broader ecological topics, such as predator-prey dynamics and habitat selection and use.

Birds of prey somehow connect in an emotional, even spiritual way with people across cultures and age groups. The ancient Egyptians considered Horus, the falcon-headed god of the sky, as one of the most important animal-gods. In one Egyptian temple, archaeologists have discovered the mummies of more than 800,000 falcons! Raptors have played a profound role in American Indian life in both religion and art. A casual glance at the Center’s Plains Indian Museum collections reveals a wide variety of garments and other materials adorned with feathers from many species of raptors. Eagle feathers, and to a lesser extent, red-tailed hawk feathers are among the most prized.

Among Plains Indian cultures, the golden eagle eclipses all other raptors as a symbol of spiritual power. Eagles and other raptors have been chosen as national symbols by many countries across the world, including the United States (American bald eagle) and Mexico (golden eagle). Sports teams and multinational corporations also use raptors to symbolize their power, speed, and proficiency, and falconry continues to be among the most popular outdoor avocations across the world. There is something magical that happens when someone, youth or adult, is introduced to a live raptor. It defies description, but it is undeniable that people are attracted to and mesmerized by an encounter with a live bird of prey. For some, it is truly a life-changing experience.

Over the last several years, we have incorporated birds of prey into the Center in various ways. For example, we have been engaged in a long-term study of golden eagle nesting ecology in the Bighorn Basin and other areas of the Greater Yellowstone region since 2009, incorporated various raptors into each of the four life zones presented in the Draper Natural History Museum exhibits, displayed interpretations of birds of prey in the Whitney Western Art Museum, and as noted above, showcased raptor feathers and other elements in our Plains Indian Museum galleries. Since coming to the Center, I’ve authored two books on raptors, along with several scientific and popular raptor articles. We’re currently developing a grant proposal for the National Science Foundation to use our golden eagle research, and Plains Indian collections and expertise, as a foundation for an engaging suite of informal and formal educational experiences directed to audiences across the nation. Following in this path, we’ve embarked on an exciting new initiative—a live raptor education program titled the Greater Yellowstone Raptor Experience.

When we were first developing the vision and exhibits for the Draper Natural History Museum between 1998 and 2002, we envisioned that the Draper would help the Center expand our walls and move beyond traditional museum boundaries in many ways. One concept that kept rising to the top—in part buoyed by that profound National Geographic moment so long ago in my grandmother’s attic—was the development of a live raptor program that would help us provide our audiences with engaging and even inspirational experiences with birds of prey in the West. We could think of no better way to fulfill the Draper Museum’s mission to increase understanding and appreciation for the relationships binding humans and nature and emotionally connect people with nature.

With so much else to accomplish, however, the idea of a live raptor program was placed on a backburner until early 2008. The Center’s new Executive Director and CEO, Bruce Eldredge, had only been on board for a few months when we had the chance to talk casually about future programming initiatives. When I described a live raptor education program, Bruce was immediately enthusiastic and supportive. He knew how popular live raptor programs were in other venues and encouraged me to pursue the concept. After some additional discussions and research, we submitted grant proposals to the W.H. Donner Foundation and Donner Canadian Foundation (the latter in partnership with University of Wyoming’s Berry Biodiversity Conservation Center) to establish the Greater Yellowstone Raptor Experience and fund operations for up to three years. Late in 2010 we received notice that our proposals were approved for funding!

Our first order of business was to recruit a dynamic, experienced, and highly skilled professional to come to Cody, Wyoming, and the Center to become our first “Raptor Wrangler” and establish the new program. “Walking on water” was only left out of the job description at the insistence of Chris Searles, the Center’s Human Resources Manager. We embarked on a national search, hoping to attract at least a couple of strong applicants for this highly specialized position. We advertised in several national raptor-related venues, and I contacted dozens of my colleagues in the raptor research and education field to spread the word.

To our delight, we received more than two dozen applications, including many highly-qualified candidates. One person stood out, though, when we began interviewing the top tier of candidates. She was highly personable, dedicated to quality education and the highest level of bird care, and possessed many years of experience in first-rate organizations. There was one problem, however; she was currently employed by my close and highly respected friend, master falconer Kin Quituqua. I even sit on the advisory board of the amazing organization, HawkQuest, that Kin operates in Colorado, and he has presented programs at the Center in past years, helping us test the waters for a live raptor program.

Kin brought a golden eagle to help celebrate the Draper Natural History Museum’s grand opening in 2002. I knew Kin valued our top candidate highly, and she had great respect for Kin. But she was also at a point in her career when she was prepared and anxious for this new challenge, and she loved Cody. So, we offered her the job, and I put in a courtesy call to Kin to give him a heads up. Fortunately, Kin was gracious, and Melissa Hill accepted our job offer. Of course, I have to find some way to make this up to Kin, and he calls to remind me of that from time to time. From my perspective, that’s fair trade!

Melissa started her job at the Center in February 2011, and has been a whirlwind since. I haven’t seen her walk on water yet, but she has certainly fulfilled our grandest expectations thus far. Even Melissa couldn’t have anticipated all the challenges of establishing a live raptor program from scratch—securing permits, acquiring birds, overseeing design and construction of raptor housing, recruiting and training volunteers, and so on. I had contacted both federal and state agencies to begin the permitting process, but it was left for Melissa to follow through and work directly with these agencies. We have a team to help Melissa, but she has ably shouldered the eagle’s share of the challenge and has already thrilled audiences with our new stable of raptors.

In [next week’s] article, Melissa will tell you in her own words what she has accomplished to date and what we’re planning for the future. This is an exciting time for the Center, and I hope we can help infuse our audiences with the spirit of exploration and the sense of awe and mystery I felt so many years ago when I was first exposed to “Adventures with Birds of Prey!”

Post 186

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.