Points West Online: Harry Jackson: 2006 Honored Artist – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2006

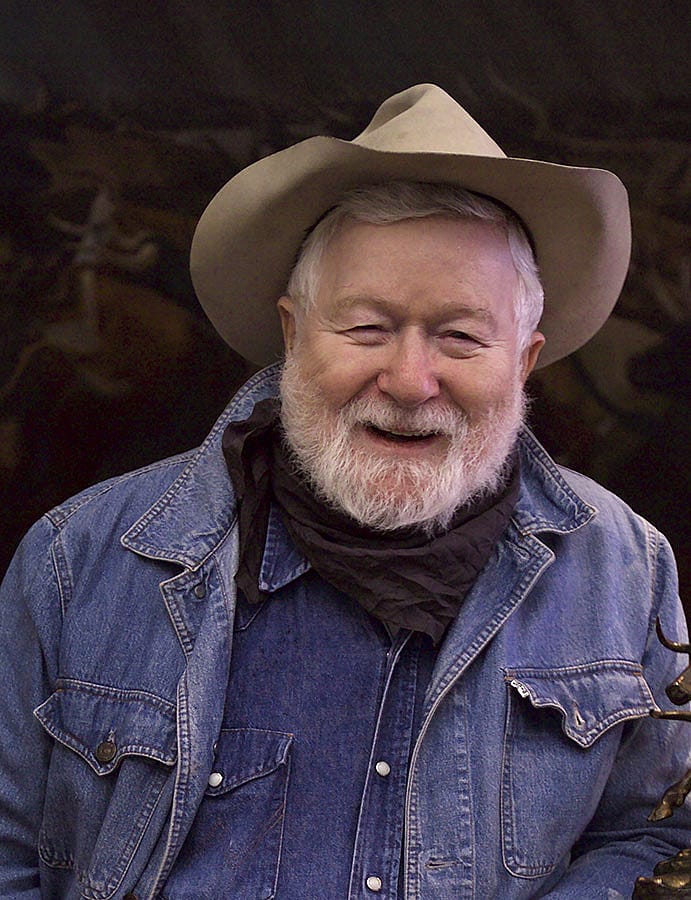

Harry Jackson: 2006 Honored Artist, Buffalo Bill Art Show & Sale

By Marguerite House

Media Coordinator/Editor, Points West

In 2003, the Buffalo Bill Art Show launched the tradition of naming an annual honored artist as a special way to pay tribute to those artists who have made important contributions to Western art. [In 2006], we’re proud to name Harry Jackson as our Silver Anniversary’s honored artist. Jackson’s works are an important part of the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West]’s collections and his fusion of radically abstract work with realistic western and cowboy themes has earned him worldwide recognition. —Deb Stafford, then-Director, Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale

I first met Harry Jackson when I was a seventh-grader in Mr. Gilpin’s art class. Because I grew up in Riverton, Wyoming, this inevitably meant a field trip up north to the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] in Cody—especially if one was enrolled in any art or history class.

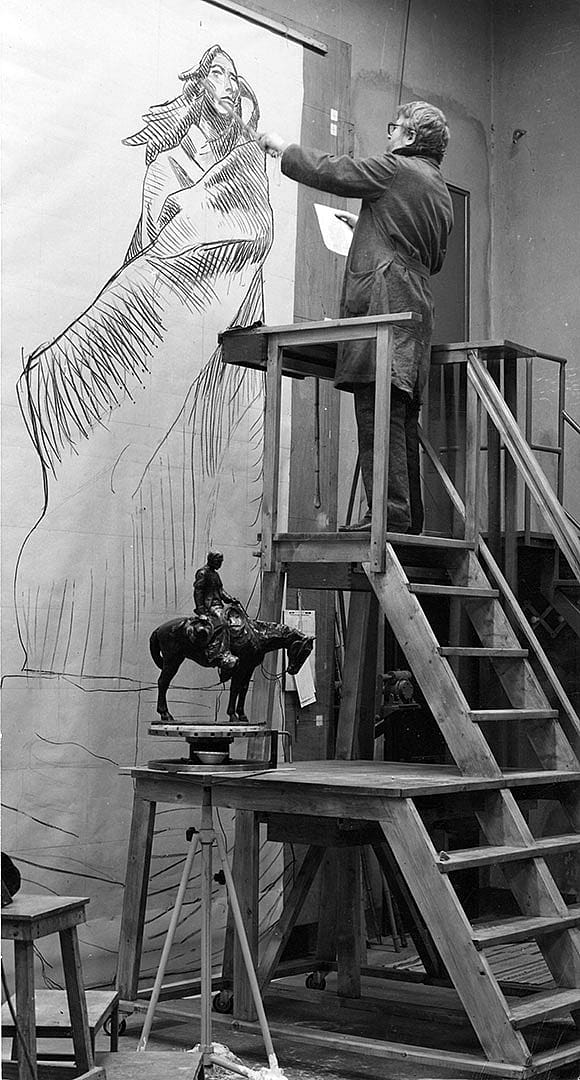

Obviously, I didn’t meet the artist “up close and personal.” I do remember, however, seeing his monumental, sequential paintings Stampede and Range Burial and being totally taken by their enormous size, some 10 feet high and 21 feet long. There were those intricate sculptures of each, too—”complex, but not complicated” as Harry would later say, a distinction he shared with me on numerous subjects. I stared and stared at them from every possible angle, matching up person-by-person and horse-by-horse to the paintings behind them.

Little did I know that a full 40 years later, I’d be writing a story about the 25th Anniversary Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale’s Honored Artist, Harry Jackson. When we met for our first interview, I was that sheepish seventh grader again with questions like: “Is it a stretch to make the leap from bronze to canvas?” “Do your eyes get tired painting something that big?” “Just how many steers are in that sculpture?” (At this last question, he looked at me with a half-wince/half-grin and said, “Hell, I don’t know! They conjure up Hell turned loose!”)

Mystic Bonds

I suppose Harry would call our meeting one of life’s “mystic bonds,” those coincidences, twists of fate, divine interventions, cosmic occurrences, or just plain meant-to-be’s that cause individuals’ paths to cross. One of the most consequential for Harry was his life’s first encounter with abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock who would become his friend and mentor.

Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and in the fall of 1942, Harry and fellow Pitchfork cowboy Cal Todd had volunteered for the Marine Corps in the fall of 1942. While friend Cal was rejected by the Marines and ended up a gunner in the Army Air Corps, Harry entered Marine boot camp in San Diego, California. Later, he became the sole combat sketch artist with the Fifth Amphibious Corps general intelligence section, and at age 19, PFC Jackson was one of the first Marines to land on Japan’s impregnably fortified central Pacific island of Betio, Tarawa, in what has been called the bloodiest amphibious conquest in human history. That 76-hour battle began on November 20, 1943.

That very day, New Yorker magazine’s art reviewer Robert Coates complimented one of Harry’s early combat sketches, Night Patrol on display in New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition Marines at War. And, in that same review, Coates complimented Jackson Pollock’s first one-man show in Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. It would be one year before Harry would consciously realize Pollack’s and his “mystic bond.”

After Harry suffered head wounds at Tarawa in 1943 and leg wounds on Saipan in 1944, he was “shipped stateside,” to Los Angeles, where, at age 20, he was made an Official Marine Corps Artist, the youngest ever. While in Los Angeles, he first saw Pollock’s The Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, which, to Harry, “expressed the bloody madness…of Tarawa better than any combat art I’d ever seen.” Harry was so taken with Pollack’s abstract expressionist painting, that he had to meet “this awesome visionary.” It would be five years before he would finally meet Pollock—the artist whom a 1949 Life magazine article dubbed “Jack the Dripper” because of his technique of dripping paint on to canvases fixed to the floor. It was Pollock who introduced Harry to abstract expressionism which, according to Harry, “notably energized my earlier realistic paintings.”

The Pitchfork Cowboy

In chatting with Harry, it’s hard to imagine he wasn’t born a cowboy. He knows horses; the lion’s share of his artwork includes horses, cowboys, and Indians; he can “spin a yarn” with the best of them; and he was a saddle hand—especially at the legendary Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming, his “place of birth” according to his Marine discharge papers.

But Harry wasn’t born in Wyoming. He was born on Chicago’s south side on April 18, 1924, the only child of Harry Shapiro and Ellen Jackson Shapiro. Ellen chose to name him Harry Jackson after her own father, but, for the most part, most everyone called him “Sunny.” Harry’s kill-for-hire father committed his first murder at age 13 and was subsequently a Mafia hit man who carried out contracts for Al Capone and George “Bugs” Moran. Harry tells how, in April of 1931, his father who had jumped bail from one of his many incarcerations, was captured in Harry’s bedroom. It was his seventh birthday and before four policemen led Shapiro away, he gave his son a fully-loaded Smith & Wesson .45 caliber revolver as a birthday present.

Harry’s mother Ellen was “leased to pedophile clients in order to force her to earn her own keep,” according to Harry, and young Sunny was destined for the same fate. Harry and his parents lived with Ellen’s mother, Grandma Minnie, in Minnie’s lunchroom cum bordello/gambling-house across South Halstead Street from Chicago’s gargantuan Union Stockyards. With cowboys a-plenty herding cattle through the maze of pens, Harry spent hours listening to tales of range life in the West. On many occasions, the cowboys and traders let Harry ride their horses around the stockyards, and it wasn’t long before Harry dreamed of becoming a cowboy himself one day.

As we talked about those early years, Harry abruptly asked if I’d seen the bloody 2002 gangster movie Road to Perdition.” In it, Mafia boss John Rooney (Paul Newman) employs Mike Sullivan (Tom Hanks) as his killer—a kind of archetype of Shapiro. Harry even repeated sizeable portions of the movie’s dialog and finally shuddered as he said, “That was my mobster Old Man.”

Given the violent nature of his home, it’s no wonder Harry became a Dickens-like urchin, roaming the streets of Chicago, “making all kinds of marks and doodles which beat hell out of going to school,” Harry said. When he was eight-years-old, teacher Ann Campaign recognized Harry’s unique gift and secured a scholarship for him in the Chicago Art Institute’s Saturday children’s classes. Harry still displays some of those early works in his studio/museum. I commented on their “sophisticated themes” (at age 13 he’d painted a boxer and a nude), and he responded, “I was as precocious as hell.”

While dodging school and his terrifying home, Harry regularly visited Chicago’s many museums including the Chicago Art Institute, the Field Museum, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the Harding Museum where he was captivated with western artist Frederic Remington’s paintings and sculptures. He also learned to ride lively horses by exercising polo ponies for the 124th Horse Artillery’s polo team near his Chicago home. “All I was good at was drawing, riding, and running away,” Harry explains.

He was determined to be a cowboy illustrator and saved numerous magazine articles as examples. One in particular was the February 8, 1937 issue of Life magazine with the photo essay “Winter Comes to Wyoming,” photographed by Charles Belden on the Pitchfork Ranch—the very one that Harry would later call his birthplace. In Chicago, he’d connected with many a cowboy at the stockyards, ridden fast polo ponies for the polo team, studied the works of western artist Frederic Remington, and was totally enamored of this cattle ranch called Pitchfork. So, just after his fourteenth birthday, Harry ran away from Chicago to the rangeland of Wyoming where, ultimately, he became the globally recognized cowboy artist.

The Seer Artist

Harry calls himself a “seer-artist,” about which “there’s really nothing special,” he says. “It is basic to all humans.” Of course, the difference between the Harry Jacksons of the world and the rest of us is that only a few seer-artists become what Harry calls “celebrators, those few who follow the call, so to speak.”

And my, how Harry followed the call. From his childhood art classes in Chicago to his cowboy escape to Wyoming to his stint in the Marines, Harry always doodled, sketched, or painted. Once he met Jackson Pollock—who, by the way, was born in Cody, Wyoming, in 1912, some 50 miles north of the Pitchfork Ranch—Harry embarked on a period of abstract expressionism as he lived among a number of abstract artists alternately in New York, then Old Mexico, and New York again. Indeed, he was gaining recognition for his abstract work, but, at the same time, was becoming less and less enchanted with modern art dealers who “changed priceless art into a commodity.”

So Harry was drawn to Europe in 1954 where he studied the Venetian painter Titian, as well as other Renaissance artists in Italy, Austria, Germany, France, and Spain. Much to the chagrin of his fellow abstractionists, including Pollock, he returned to painting realism, though “notably energized by his recent years of abstract expressionism,” according to his online biography (www.harryjacksonstudios.com).

Harry’s abandonment of New York’s abstract expressionists was big news in the art world. His life-size painting The Italian Bar was featured in the July 9, 1956, Life magazine photo essay Harry Jackson Takes the Hard Way, in which author Dorothy Seiberling commended Harry for abandoning Pollock’s expressionistic work for those of the great European masters. On the other hand, New York Times art critic Dore Ashton damned Harry for “daring to betray his mentor Pollock’s skyrocketing success.” Another critic at the Times, Hilton Kramer, wrote, “It [Harry’s return to realism] has certainly made Mr. Jackson’s fortune, but it has all but robbed him of his fame…. Most of the cowboy sculptures are unfortunately the sheerest kitsch. Their every gesture is cliché.”

The Philosopher

“Don’t impose your images on the work. Open yourself, and be as neutrally and lovingly receptive as you can be,” Harry advises. “This is the way to look at any work of art, no matter how realistic or abstract it may be. Just let it happen to you.” Even though Harry was willing that I take away whatever I could from his work, I suppose I felt, on some level, unqualified to make any kind of analysis or judgment without consulting “one of those so-called ‘professionals.'”

Once Harry shared with me a lifetime of stories behind the myriad of paintings and sculptures in his studio—The Italian Bar, Two Champs, The Marshal (John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn from the movie True Grit) for the August 8, 1969 cover of Time magazine, a scale model of his circa 22-foot equestrian sculpture The Horseman created for the Great Western Financial Corporation headquarters in Beverly Hills, to name only a fraction—he waxed philosophical, as they say, about life and about art.

The questions I had for Harry came fast and furious. I couldn’t help but ask questions about his life, his relationships (he’s had six wives/significant others), his friends, and his art. When I asked Harry about his talent, he was quick to interrupt as he loathes the word “talent,” “because talent in the Bible means money.” “No, I prefer to call what I and folks like me do—a gift.”

I asked Harry if he felt his gangland father was evil. Harry replied simply and quietly, “He was my father.” (Ironically, Harry was to discover years later that his father had actually enrolled in art classes at the Barnes Foundation in Marion, Pennsylvania about 1946.) Then, I asked how his life might have been different had it not been for his art, a question met with yet another of Harry’s wince/grins. “I don’t know,” he replied. “All those wouldas, shouldas and couldas are a waste of time. One’s life is simply what it is at every eternally here and now moment.”

I was also curious how Harry viewed abstract art and discovered a veritable dichotomy. To Harry, even though a piece of art may look abstract, “it ain’t necessarily so. In fact, it might be quite the opposite. It can be totally not abstract-expressionist, even not non-objective.” He used the work of Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky as an example of what is realistic, by noting the artist’s desire to paint music on a flat surface. “He used colors, lines, and inter-relationships that may look abstract, but are in fact music on a flat surface—a very real, palatable subject.”

However, in the sense that art isn’t truth—one can’t eat the bowl of apples in a still life, for example, or hear the noise of hooves in Harry’s own Stampede—”it’s all basically abstract and non-objective,” in Harry’s view. Oddly enough, it made perfect sense.

Our interview concluded, I looked over my notes and photocopies and realized I could have written volumes more. A story about a life of 82 years is guaranteed to do that, I suppose—especially about an artist as colorful as Harry Jackson. The writing brought me back, full-circle, however, to when I first caught sight of Harry’s Stampede during that seventh-grade art class visit. And that question about the number of longhorn steers in the sculpture? I counted them. There are 30.

In our next post: a look at Harry’s painted bronze, Sacajawea.

Post 195

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.