A New Exhibit Takes Flight in the Draper Natural History Museum – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2018

Monarch of the Skies: The Golden Eagle in Greater Yellowstone and the American West

By Charles R. Preston, PhD, and Bonnie Lawrence-Smith

It was truly a dark and stormy night. The storm brought torrential rain, sleet, snow, golf-ball-sized hail, and wind—Wyoming-level wind! It had driven us from the field the afternoon before, and now we were back to discover the storm’s effects on the newly-hatched golden eagles we had documented in several nests the previous week. The morning was cool and damp, and the sky was still drenched with gray clouds. The first nest we checked left us worried for the rest of the nesting population. We scrambled, slipped, and scrambled again up a nearby hill overlooking the nest site. After focusing our powerful spotting scope on the distant nest, it became clear that the two downy eagle nestlings we had seen the day before were now missing.

Neither was there any sign of the parents, and a portion of the nest had broken away from the cliff face. This nest site was particularly vulnerable to weather because there was only a small rock outcrop to protect it from above. After observing the nest for a few hours without detecting any activity, we searched the muddy area below the nest. Nothing. We presumed the nestlings dead and the nest abandoned for this breeding season.

We moved on with a growing sense of gloom that matched the sky. As we approached the next site, we observed one adult eagle flying just below the clouds nearly a mile away from the nest that had been home to two eagle nestlings a few days earlier. We placed our scope several hundred yards away for a good view into it without disturbing any eagles that might be nearby. At first, the nest appeared empty. But, as we watched in dread, we detected a distinct movement at the very back of the nest. Soon, two white, downy eaglets came into view! They were alive, but looked weak and a little ragged. We could not see any prey remains in the nest and worried that the parents may have abandoned the nest in the aftermath of the storm.

Suddenly the big, adult female appeared from the low-hanging clouds and perched on a nearby limber pine snag. She had brought a freshly killed cottontail for breakfast! We watched as she delivered the rabbit to the nest and began tearing bits of flesh from the carcass to feed her little offspring. It turned out that most of the nests and eagle nestlings we surveyed that day had survived the freak June storm—a testimony to well-placed nests; dedicated, attentive parents; and eons of natural selection.

This is only one of countless dramas that members of our Draper Natural History Museum research team have experienced since 2009 when we began the long-term golden eagle/sagebrush-steppe ecology study we’ve reported on in past issues of Points West. The golden eagle is an apex predator in the Bighorn Basin and other sagebrush-dominated landscapes that have been disappearing, shrinking, and changing during the last several decades. Unfortunately, this iconic western landscape that once dominated much of the American West is often overlooked and undervalued in the shadow of the dramatic heights and gaudy majesty of the Rocky Mountains. But when you work daily in the sagebrush landscape—if you’re paying attention—you can’t help becoming enchanted by its dynamic nature, unexpected beauty, and the complex stories and mysteries it reveals.

And the golden eagle is the fascinating and charismatic celebrity of this place. It is also ecologically significant, providing a barometer for detecting environmental integrity and changes. Recent studies have indicated that while golden eagle populations in some areas of western North America are declining, others are stable. Wildlife managers and scientists are concerned, however, that even this stability will be short-lived with the rapid loss of habitat and increasing sources of mortality. To help prevent significant population declines and crisis management in the future, it is important to document and better evaluate the status, population dynamics, and ecological role of the golden eagle in local study areas across the species’ range.

The saga we began unraveling in the Bighorn Basin went far beyond the golden eagle; it encompassed the complex interactions among predator, prey, and environment, and the influence of human land use changes on these interactions. Early in our study, it became clear that we had a compelling story to tell. We now had an exceptional opportunity to share our field-based experiences and discoveries to the public through field tours, programs, publications, and possibly an exhibition.

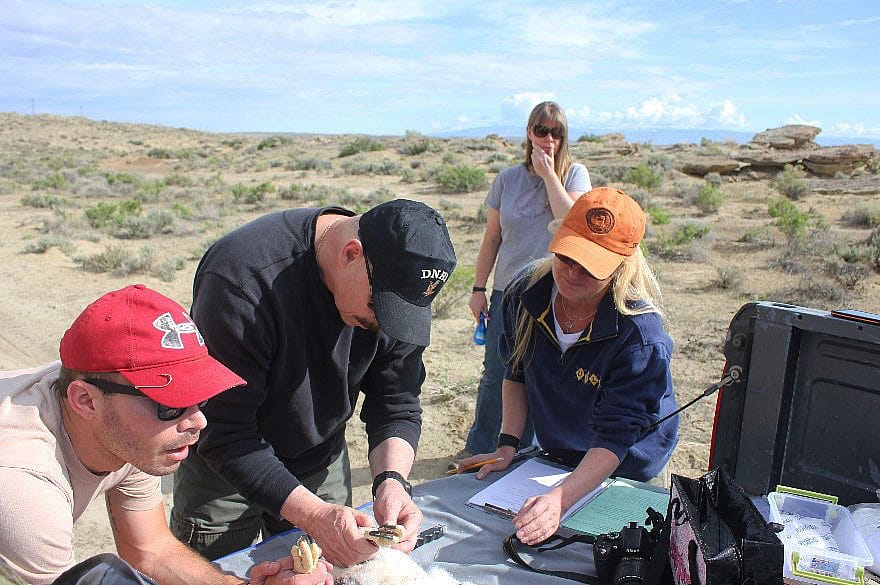

While many museums traditionally build exhibitions focused on artwork, artifacts, and other materials, natural history museums typically create exhibitions around stories or ideas using specimens and other materials to help illustrate the stories. When research assistant and photographer Nick Ciaravella (aka Moosejaw Bravo Photography) joined the Draper Museum field crew in 2015, we asked him to use much of his time and his exceptional photographic skills to help document the subjects of our research and our work in the field. Initially, we thought we could tell our story exclusively through photographs. But, as national interest grew, and we strengthened existing partnerships and established new collaborative relationships with all levels of government agencies and other researchers, we realized this story warranted a more robust and lasting vehicle.

By the end of the 2013 season, we had decided to create a major, interdisciplinary, and multidimensional exhibition to extend the Alpine-to-Plains Trail exhibits in the Draper. The gallery adjacent to the Draper’s popular tile map of Greater Yellowstone, just outside our Draper Museum Discovery Laboratory, is the perfect setting for this new exhibition. Its location, down the ramp from the Plains/Basin exhibit environment and outside our laboratory, makes it ideal to showcase the Draper’s own golden eagle research conducted in the shrub-steppe country of the Bighorn Basin.

The initial concept took on a new, exciting dimension, when we recognized that we had a unique opportunity to partner with the Center’s Plains Indian Museum. The plan would enrich our story with the addition of eagle-related ethnographic materials and insights of Plains Indian cultural associations with the golden eagle and its environment. Plains Indian Museum Curator, Rebecca West, became a key member of our exhibit development team. By early 2016, we were ready to contact an external exhibit design and fabrication studio.

We had been working very closely with Chase Studio, Inc. for several years to enhance and update our natural history exhibits annually. The firm’s principal, Dr. Terry Chase, is world-renowned for his exhibit design and fabrication skills, and he knows the Center and Draper audiences, physical layout, and facilities intimately. Chase Studio, working closely with our team, completed the exhibit design drawings and plan in early 2017 and began fabricating key exhibit elements in their extensive facilities in Cedar Creek, Missouri. With the completed design renderings in hand, we began writing grant proposals for the exhibition. And, we decided on a title—Monarch of the Skies: The Golden Eagle in Greater Yellowstone and the American West.

As you descend the ramp from the Draper’s Plains/Basin exhibit environment, you encounter Monarch. The gateway section of the exhibition immerses you in the Bighorn Basin as two large sandstone cliffs and a breathtaking video presentation introduce you to our study area, the wildlife that inhabits it, and our research team in action. One of the cliffs features a large golden eagle nest, and two golden eagles greet you from above, one perched and one flying toward the nest.

Beyond the introductory area, the exhibition features sections highlighting golden eagle ecology and natural history, sagebrush-steppe distribution, and changes in Greater Yellowstone. It also includes Plains Indian associations with eagles; the adventure, excitement, and trials of field exploration and discovery; and conservation challenges and innovative, new opportunities emerging to help protect golden eagles and associated wildlife.

One theme woven through the exhibition is the importance of scientific research to wildlife conservation and management. To that end, we present some of the key adventures and results from our own study on reproduction and diet of golden eagles in the Bighorn Basin compared with a network of similar studies across Greater Yellowstone and the American West.

Additionally, families can “visit” distant sites and learn about studies and research teams in Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Yellowstone National Park, and other key locations. We enhance the exhibition’s rich stories with natural history specimens (including actual prey remains recovered from golden eagle nests and an articulated golden eagle skeleton cast); Plains Indian materials including a feather bonnet, talon necklace, and wing fan; interactive touch screens and audiovisual presentations; large, colorful graphic panels, and a large selection of stunning, color photographs of wildlife, including golden eagles, pronghorn, burrowing owls, badgers, and other species in the dramatic landscapes where we encountered them.

The exhibition is designed to engage, satisfy, and excite curious minds of all ages. One of the simplest and most popular elements of the exhibition is sure to be a life-sized silhouette of a soaring golden eagle positioned so that you can compare your “wing-span” to that of this magnificent aerial predator. This and other elements in the exhibition provide splendid photo opportunities. We’re also adding a new station with a soaring eagle to emboss the Draper Museum passports as a lasting memento.

To extend and expand the experience of the exhibition, we are creating a Monarch website with “Dig Deeper” pages containing more photographs, video clips, interviews, and information related to each of the content areas of the exhibition. Draper and Plains Indian Museum staff, together with the Center’s Interpretive Education Department, are also developing online classroom modules and a suite of educational programming launched from the Monarch of the Skies platform.

The exhibition is a wonderful connections to our highly popular Draper Museum Raptor Experience, too. We now feature ten live raptors—including Kateri, our own golden eagle—in both in-house and outreach programs managed by Melissa Hill and Brandon Lewis, and supported by nearly twenty volunteers. And because the exhibition remains in the Draper far into the future, we can update and enhance the experience for years to come. For example, we’re exploring technologies that provide visitors with opportunities to experience simulated eagle flight across a North American migration route and to detect an eagle approaching a wind farm with a challenge to shut down one or more turbines to prevent a deadly collision.

Monarch of the Skies is a natural addition to the Draper Museum, highlighting our own original research in the broader context of exploring and celebrating the profound relationships binding people with nature in Greater Yellowstone and the American West. Following Members and Partners opening events on June 8–9, 2018, the exhibition opens to the public. Keep up with exhibition progress here.

Dr. Charles R. Preston is the Willis McDonald, IV Senior Curator of Natural Science and Founding Curator-in-Charge of the Draper Natural History Museum.

A Flash of Lightning and a Clap of Thunder

By Bonnie Lawrence-Smith

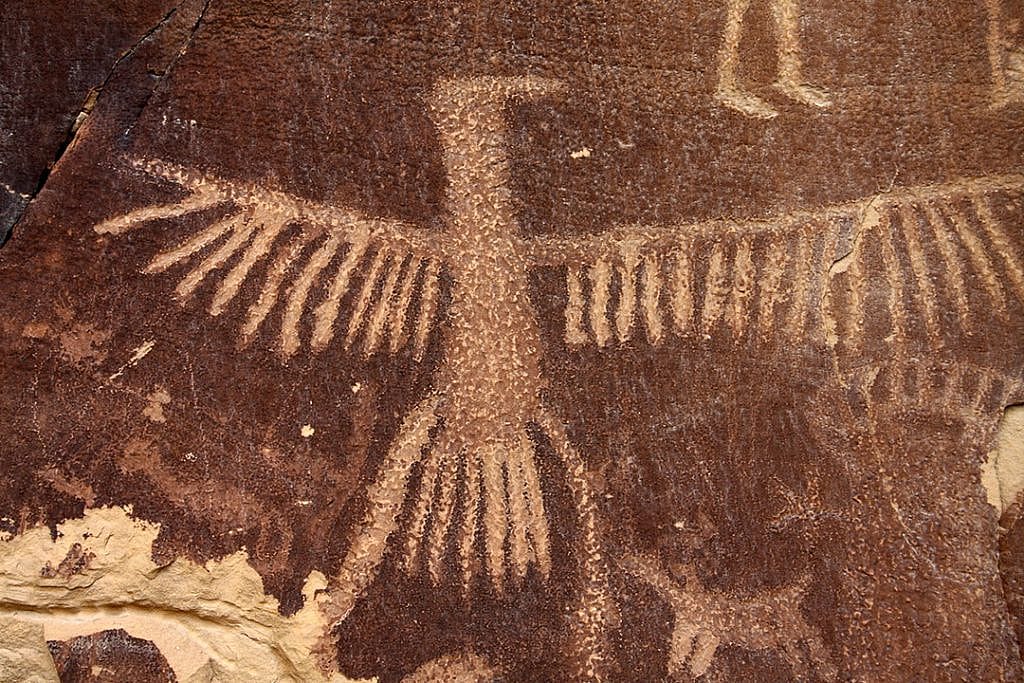

I remember clearly the first time the idea came to me: Was it possible there was a correlation or relationship between golden eagle nesting locations and Native American rock art—thundrebird figures specifically? For these peoples, thunderbirds are known to be messengers tot he Creator. The flapping of their wings creates thunder, and as the opening of their mouth and eyes generates lighting, the term “thunderbird” originated.

It was my first adventure in the field with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Draper Natural History Museum crew of staff and volunteers in 2013. Bundled up that chilly October morning, we piled into our field vehicle, “Old Blue,” ready to see some birds—specifically raptors. Loaded with several cups of coffee and my Nikon camera, I had no idea where the day would take us with Dr. Preston (chuck) leading the charge. We drove south toward Meeteetse first where Chuck pointed to the rough-legged hawks (Buteo lagopus). The telephone poles and irrigation wheel lines were littered with them.

Then, we turned east toward Burlington, and the fun really began. Golden eagles were everywhere! Eventually, turning back toward town, we came to a gate adjacent to YU Bench Road, and Chuck announced, “Just over there are three nests.”

“All together?” I asked.

“Yep, and there are some petroglyphs out here, too,” he replied. I remember thinking, “Isn’t that interesting?” We returned to the Center where I searched out then Plains Indian Museum Curator Emma Hansen. I asked her if she knew of any research that had been done on golden eagle nest sites and Native American rock art. She said no, but agreed that it could be interesting. The connection seemed so obvious—so much so, that I found it hard to believe that modern scholars hadn’t made the same connection sooner.

I spent four years researching this idea. In 2015, I began using Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office site forms to identify possible rock art sites that may or may not support my hypothesis. Some scholars have suggested site location was incidental. Some data indicate, however, that these locations may have been carefully chosen for landscape features, spiritual significance, and available resources that are site specific, such as water and white clay.

I have identified more than fifty archaeological sites in the Bighorn Basin that could offer evidence to support my hypothesis. I suggest that Native peoples were seeking out specific locations—where golden eagles nested—to leave their messages to the Creator or Great Spirit.

In Rupert Weeks’s book Pachee Goyo: History and Legends from the Shoshone, 1981, the main character, Pachee, must ritualistically purify himself in a lake (water) and cover his entire body in white clay to demonstrate that his heart and soul are clean and ready to obtain his “medicine.” Pachee describes the animals and fantastic creatures carved into the rock face of this spiritually significant place. His grandfather told him that “whenever you see a drawing high on the face of steep cliffs, you will know that is where the Great Spirit dwells.” These are the places to go to acquire one’s “medicine,” i.e., the power to heal. As Pachee sleeps that night, he dreams of a radiant figure holding a golden eagle and singing a medicine song of healing. In this dream, the figure plucks one feather from the golden eagle’s wing and gifts it to Pachee. Upon waking, he finds a single golden eagle feather, an act representing his receipt and acceptance of his “medicine,” bestowed upon him by the Great Spirit.

I have researched nesting locations, archaeological sites, and the material record; read the legends and myths of Plains Indian people; and interviewed living Native Americans. As a result, it’s clear to me that the golden eagle, or “thunderbird,” has always held, and continues to hold, a revered status among Native people of the Plains. I believe it deserves our protection.

Bonnie Lawrence-Smith was formerly the Curatorial Assistant of the Draper Natural History Museum.

Post 197

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.