Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine Fall/Winter 2017

Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West

By Peter H. Hassrick, PhD

Unless noted otherwise, all works were created by artist Albert Bierstadt, and all paintings are from the collection of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Each painting mentioned was part of the Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West special exhibition at the Center of the West in summer 2018, followed by a tenure at Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

In summer 2018, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West opened an extraordinary exhibition of the works of nineteenth-century artist Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902). Here, in a Points West article from the winter before, western art scholar Dr. Peter H. Hassrick offered a preview of that highly anticipated show.

Through the summer of 1888, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody camped with his Wild West troupe on Staten Island, New York. It was not unusual for artists of all sorts to be wandering the grounds and attending the performances, but that year there was a particularly distinguished painter frequenting the show. His name was Albert Bierstadt, perhaps America’s most celebrated landscape artist. He was there, however, not to refresh the giant landscape backdrops that Cody used to surround his arena, but to gain inspiration for a pair of monumental history paintings symbolizing the demise of the bison and the native cultures of the Plains that depended on them. The resulting works are both titled The Last of the Buffalo [Fig. 1]. Today, one version graces the walls of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the other, belonging to the Center’s Whitney Western Art Museum, is the centerpiece of the first major Bierstadt exhibition and book in more than a quarter century, Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West.

Bierstadt had first seen the Northern Plains Indians during his maiden voyage west in 1859. At age 29, he had recently returned from several years of art studies in Germany where he concentrated on landscape and figure painting. The West offered stunning mountain geography and fascinating indigenous cultures, and in his paintings, the artist relished in combining grand vistas with Native people like Sioux and Shoshone Indians. For excitement, he often introduced a buffalo hunt into his pictures as well [Fig. 2]. His first highly acclaimed canvas of the period, Base of the Rocky Mountains, Laramie Peak (1860, now lost), was such a work. Shown at the National Academy of Design in New York, it was touted as truly remarkable and “the largest and most elaborate picture in the exhibition.” It merged three elements: western mountain majesty, dramatic Plains hunters, and the frontier’s iconic bison.

However, subsequent grand-manner paintings like his masterpiece The Rocky Mountains, Landers Peak, 1863, attracted critical censure [Fig 3]. Denounced for combining two powerful fundamentals into one composition, Indians and mountains, Bierstadt diverted from portraying his beloved Indians and forced himself instead to focus on sublime mountain panoramas like Yosemite, Colorado’s Rockies, and the Yellowstone region.

In addition, as the Indian Wars developed during the 1860s, Indians became less and less viable as subjects. Rather than picturing the Native people of the West in a bad light, Bierstadt turned his artistic attentions to what he considered a fitting surrogate—the buffalo. The Plains people were a buffalo culture. Everything in their world depended on the bison, from their economic and social structure to their spiritual and political life. It was therefore appropriate for Bierstadt to conflate the two [Fig. 4].

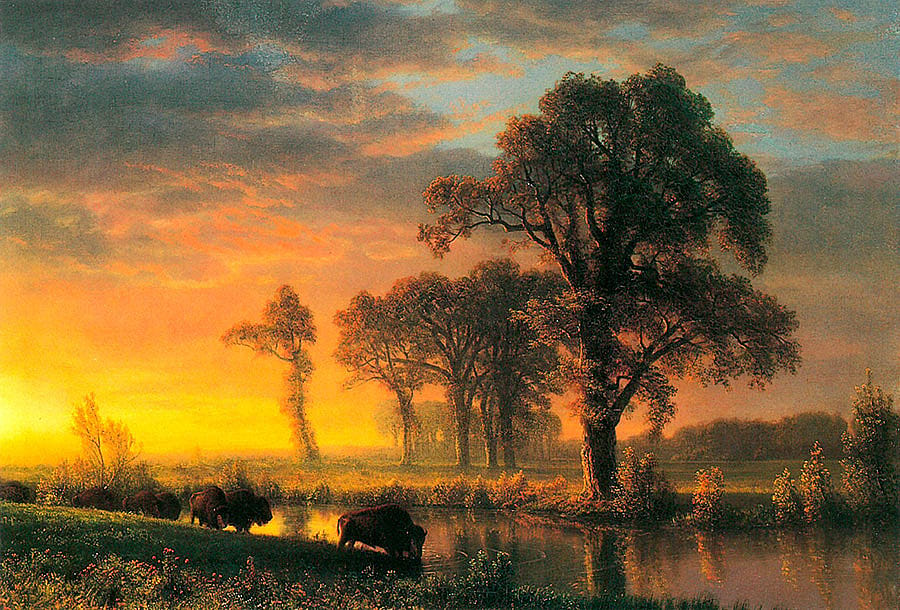

What subsequently began to happen to the buffalo with the hide hunters of the 1870s—devastating the herds to the point of near extinction—could be seen in a collateral way with Native populations. In the late 1860s and throughout the 1870s, as the Indians were relegated to smaller and smaller reservations, and the slaughter of the bison became commonplace, Bierstadt painted a series of three seminal narrative oils to tell the story. His 1867 Buffalo Trail [Fig. 5] spoke of the halcyon days of the buffalo as it showed a healthy herd of bison crossing the Platte River and arriving in a lush meadow of verdant grass. The message was regeneration and promise for the future.

![Fig. 4, "Head of Buffalo and Indian," ca. 1859. Oil on board. Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles, California. 88.108.14 [L.2018.6.1]](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=450,height=327,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PW198_Fig4-HeadOfBuffalo-Autry.jpg)

Bierstadt’s Buffalo Trail: The Impending Storm [Fig. 6] followed in 1869, the year the transcontinental railroad was completed, and divided the western buffalo herds in two. Here the herd is greatly reduced and appears to be in great peril. The distraught animals retreat to the dubious protection of a few trees and rocky cliffs. Then in 1876, in sardonic recognition of the nation’s centennial, he painted a work for a huge, celebratory exhibition in Philadelphia. Instead of exalting the country’s illustrious past, however, Western Kansas [Fig. 7] dramatized its gloomy present.

In this work, the bison follow in somber procession along a darkened stream with an ominous sky in the background. They are like beasts preparing to cross the mythical River Styx on their way to oblivion. The title was appropriate to the moment, too, as the state of Kansas was the center of the western hide trade. In one year alone, 1873, nearly a million hides were shipped from its railheads to the East to be used as the mechanical belts that drove insatiable American industry. His final masterpiece, The Last of the Buffalo [Fig. 1], is emblematic of those continuing tragic times. In the painting, the buffalo and the Indian die together in a heartbreakingly dire pictorial apotheosis.

In the mid-1880s, Buffalo Bill made his voice heard about what was happening. He lamented the shoddy treatment of the Indians by the government and the virtual extinction of the West’s grandest mammal, the bison. There was a small remnant herd of buffalo still alive in Yellowstone National Park, and they were being systematically poached to death. Cody called on Congress and the American people to rally behind these survivors, and to pass laws to protect the animals in this unique natural sanctuary.

By January 1888, a group of conservation-minded gentlemen calling themselves the Boone and Crockett Club formed in New York to press for the same measures. Theodore Roosevelt was the president of the organization and conservationist George Bird Grinnell, an officer. Roosevelt had a strong political voice and Grinnell, as chief editor of Forest and Stream magazine, enjoyed an influential editorial voice. Bierstadt was a charter member of the club as well and, no doubt, wondered what he might do to further the cause. His solution was to paint those two grand-manner history paintings, The Last of the Buffalo [Fig. 1], and bring the issue to the forefront nationally and internationally through art.

One of the two works was shown at New York’s fashionable Union League Club and then in Paris at the 1889 Salon, the same year Buffalo Bill took his Wild West to France in conjunction with the world’s fair, the Exposition Universelle. It received broad press coverage as a result. The other version was displayed three years later in a London sales gallery where it commanded $50,000, the largest price ever paid for an American artwork in the nineteenth century. The works had made a monumental splash and, given their powerful theme, helped the club win a victory in Congress when it passed the Yellowstone Protection Act in 1894, providing legal recourse for Park personnel to handle poachers in proportionate and summary fashion.

The Indians in Buffalo Bill’s troupe had watched Bierstadt make sketches of buffalo [Fig. 8] and themselves during the artist’s 1888 Staten Island summer visits. They also saw both versions of Last of the Buffalo, first in Paris in 1889 and then again in London in 1891. Rocky Bear, the Sioux leader of a troupe of about thirty Oglala, brought a large contingent of his people into Paris on numerous occasions to view the painting there. The assembly had such a presence that a reporter from the New York Times interviewed Rocky Bear. The Sioux leader summed up his impressions by adulating Bierstadt for “giving breath and life to the glorious past of the redskin and to the buffalo, when the Indian was master of all he could survey.” The artist had returned to the theme of his first masterwork, Base of the Rocky Mountains, Laramie Peak, celebrating the union in life and death of the three great forces of the early West—the vast geography, the vibrant Plains people, and the noble bison.

The Exhibition

Comprised of seventy-two objects, Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West is a joint venture with Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The exhibition is on display at the Center of the West, June 8–September 30, 2018, and then at Gilcrease, November 4, 2018–February 10, 2019. In conjunction with the exhibition, the Center of the West and the University of Oklahoma will publish Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West. The book contains essays by Peter H. Hassrick, Karen B. McWhorter, Emily Burns, Dan L. Flores, Laura Fry, Melissa Webster Speidel, and Arthur Amiotte.

A prolific writer and speaker, Peter Hassrick was recently honored by the University of Wyoming with an honorary doctorate degree. He has served as guest curator of numerous exhibits nationally and internationally. He was a former twenty-year Executive Director of the Center of the West and has served tenures directing the Denver Art Museum’s Petrie Institute of Western American Art, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, as well as working as collections curator at the Amon Carter Museum. He is currently Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar for the Center.

Post 198

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.