The Bell Family Collection – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine Spring 2006

The Bell Family Collection: A Hair-Raising Tale from the Archives

By Juti A. Winchester, PhD

All photographs are gifts in memory of William A. Bell and Leonard Cody Bell by Frances Slattery and Guilbert.

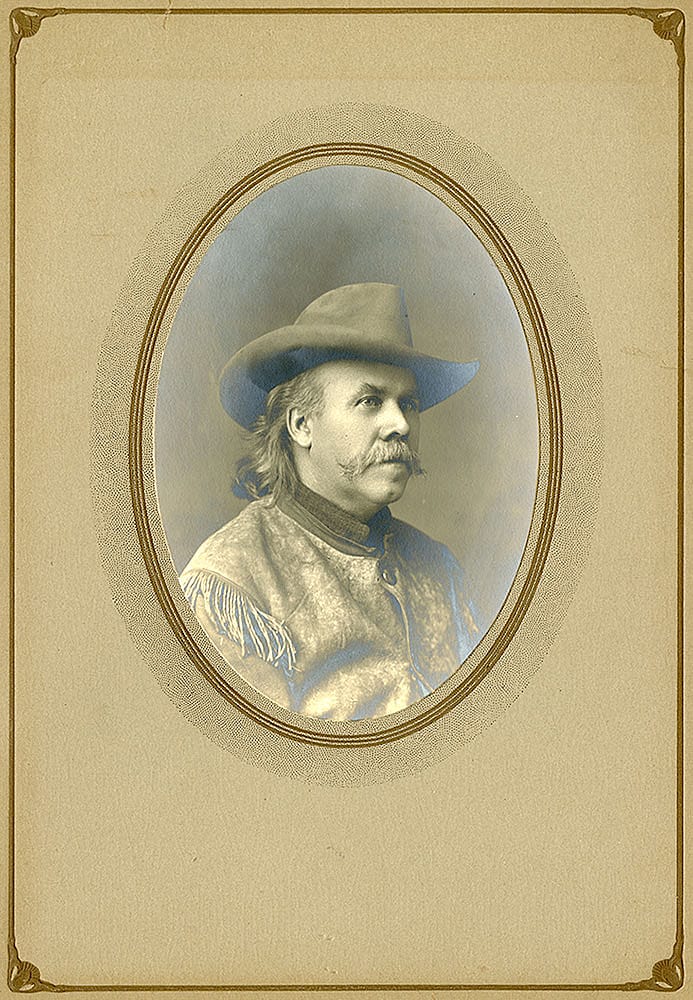

An archive is one of my favorite places. A person can spend days transported into the past simply by opening a box, which is what happened to me when I studied a collection in the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West]. These materials had once belonged to William A. Bell and his son, Leonard. The elder Bell was a friend of William F. Cody and the collection included several letters between the two men. Named after his father’s friend, Leonard Cody Bell (known as Cody to his friends and “Code” among his sisters) had also been a favorite of Buffalo Bill. He even traveled with the Wild West in 1912 and, along with the letters, a pile of photographs, and a scrapbook, the collection included the silver cornet Cody Bell played while with the show.

Despite all of the materials in this fine collection, we are still not sure how William Bell and William Cody first met. Born in Scotland in 1855, Bell immigrated to the United States with his family in 1861. By the 1870s, he had a patent office in San Francisco and worked at this trade for some years. Bell eventually settled near his parents in Iowa, where he started his own family and operated a show printing business. Somewhere along the line, Bell came to personally know some of the famous figures in western lore, including Jack Crawford the “Poet Scout” and W.F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

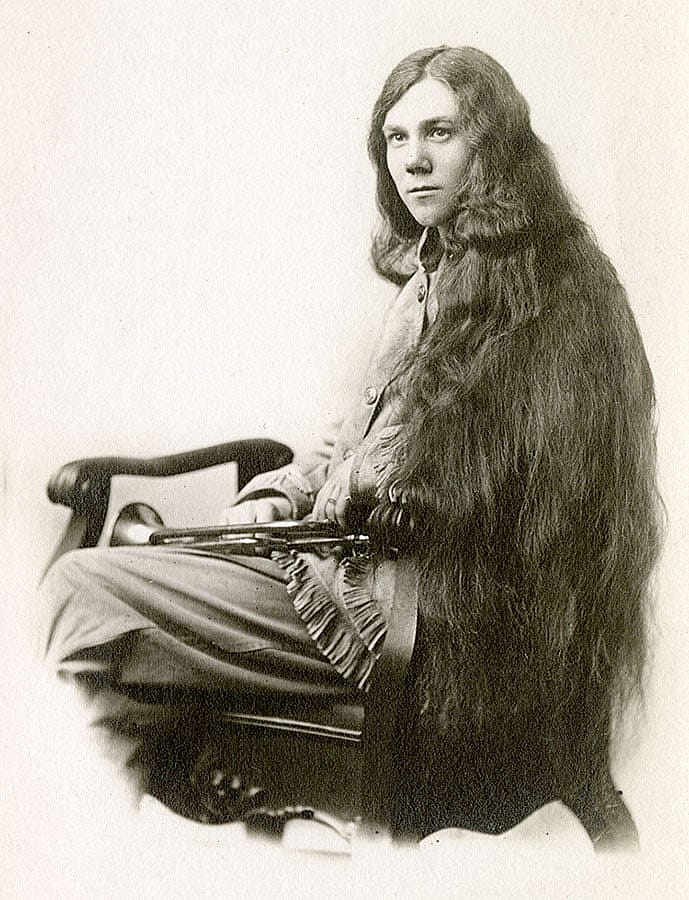

Among the usual snippets of poetry and family photographs that one would expect to find in a nineteenth century man’s scrapbook, Bell kept news-paper articles about the Poet Scout and Buffalo Bill. He clipped a number of American patriotic essays and poems interspersed with articles of interest about Scotland. While there isn’t much about Mrs. Bell, there are some clippings about his daughters, May and June. Much of the scrapbook is related to the Bells’ son Cody, who had a knack for attracting attention by virtue of his beautiful hair. You probably have pictures like these in your own family collections—photographs of your grandfather or another relative wearing short pants and hair arranged in long curls. Around 1885, the velvet and lace suits and sausage curls of the “Fauntleroy” style became popular with the parents of young boys, and remained fashionable into the early twentieth century. A handsome child born in 1894, Cody Bell wore the Fauntleroy suit and curls and carried them off charmingly.

At some point, William F. Cody made a deal with William Bell. Placing a large sum of money in the bank, Buffalo Bill challenged him to keep his son’s hair uncut until he was eighteen years old, and if he did, Cody Bell could claim the money. Mrs. Frances Guilbert, who donated the Bell Family Collection to the [then] Buffalo Bill Historical Center in 2004, remembered that the amount of money promised to her “Uncle Code” was $10,000.

Cody Bell kept his end of the bargain, despite complications presented by his unusual looks. When he was a teenager, a friend measured Cody’s hair at 58 inches long! By all accounts, Cody was unhampered by his ponytail and even went on to do well in military school, winding his locks into a large bun pinned under his hat to get into uniform. On his way to participate in a series of National Guard encampments in 1910, Cody Bell was arrested three different times by police, who mistook him for a girl in boy’s clothing. Each time, they released him when he demonstrated that he really was a boy, and no further questions were asked when Cody explained that Buffalo Bill had asked him to grow his hair long. “Bell likes soldier life,” the newspaper observed. “Among the soldiers he is called ‘The Daughter of the Regiment.'”

One journalist described the scene when Cody let his hair down to show someone how long it was. “In five minutes the store was packed with a curious, admiring crowd and they had to lock the door to keep the crowd back from the sidewalk. It required the services of two police officers to clear the sidewalk.” The writer went on to note that Cody had “captured a score of hearts of the young ladies as well as the older ones.”

Most of the photographs in the collection show Cody Bell as a young man with a winning smile, and he seemed to be popular with everyone whom he met. At one point, he and his sisters sat for a portrait session with an unknown photographer, and for one picture Cody borrowed his mother’s elaborate hat and muff. We can only guess how much of a prankster he must have been.

Did Buffalo Bill keep his end of the bargain? We don’t know for sure, since no written record of a large withdrawal of money came with the collection, but the families remained friendly for years beyond the end of the agreement. When Cody Bell was 17 years old and had just graduated from high school, Buffalo Bill invited him to realize his lifelong ambition to join the Wild West and to bring his cornet. Proudly, William Bell printed stationery for his son’s use proclaiming “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 1912 Season.” Cody’s hair became an attraction in itself as he played in the sideshow band.

Time marched on, and the world changed for everyone. The United States entered World War I and in 1918 Cody Bell finally cut his hair and joined the Army. Sergeant Bell served honorably with a medical detachment in France, and later in the band. After the war, Cody returned to his home in Sigourney, Iowa, for a few years before moving to Baltimore, Maryland, to pursue business interests. He died only a few months after his father’s passing in 1934, but the Bell Family Collection records his remarkable story. It is only one of the hundreds of fascinating tales to be discovered in the archives at the McCracken Research Library.

Juti Winchester, PhD, was formerly the Ernest J. Goppert Curator of Western American History at the Buffalo Bill Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Post 199

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.