Build It and They Will Come – the Center’s evolving facility – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine Spring 2006

Build It and They Will Come—The Center’s evolving facility

By Phil Anthony

Operating Engineer

One of the great challenges faced by nearly all new employees, volunteers, or board members of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West is finding one’s way through all the strange subterranean passages, bare concrete hallways, and weird little office or vault areas which link the building together in places visitors never see.

Like a medieval castle or palace in Europe, the building has evolved over time. Unlike many of those palaces or castles—at least from what I’ve read about them—every space in this building still has a function; and however confusing the bowels of the building might seem, there is cohesiveness and unity to the structure.

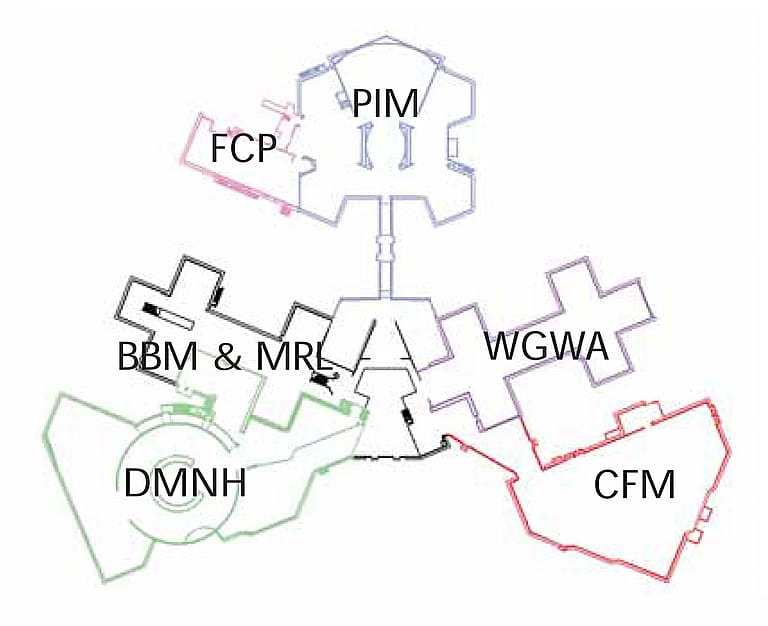

The concept of “five museums under one roof” links together such diverse disciplines as the life of Buffalo Bill, Western Art, Plains Indian culture, historic firearms, and the natural history of the Greater Yellowstone Area in order to create a unified whole in western American studies. In the same way, those efforts toward unity are reflected in the building itself.

Today’s Center is the result of six major construction projects. The first, the Whitney Gallery of Western Art [now the Whitney Western Art Museum], was built in 1959 with its stone façade and peaked roofline—which basically defined the architectural style for the construction that would follow. Next, in 1969, the Buffalo Bill Museum (a mirror image of the Whitney floor plan) and the center Orientation Gallery were built and took the peaked roofline literally to a whole new level.

Ten years later, in 1979 the Plains Indian Museum was completed, again using the stone façade and soaring roofline seen in the Orientation Gallery. Interestingly, the roof of the Plains Indian Museum reaches even higher into the sky than does that of the Orientation Gallery, but because of its location at the back of the complex, it rarely gets noticed. Fortunately, that high roof lends a better perspective for viewing the buffalo hide tipi seen in the “Seasons of Life” exhibit.

The Cody Firearms Museum was the next major expansion, completed in 1991. While it didn’t have the dramatic rooflines seen in earlier additions to the building, it remained faithful to the “grand concept,” again incorporating the stone façade used in all previous additions. Even the Draper Natural History Museum, completed in 2002 and a radical departure in many respects from the more angular architecture of its predecessors, uses the trademark stone façade of large moss rocks to unite its circular design with the rest of the building.

While it isn’t an expansion of exhibit space, the Facilities/Central Plant (FCP), completed in 2001 is, nevertheless, an important addition to the Center. Sandwiched between the Plains Indian Museum and the Draper Museum, the FCP is often overlooked for a number of reasons. First, its construction took place during the remodeling and reinstallation of the Plains Indian Museum, which commanded the most attention. As noted before, the FCP added no new exhibit space. Finally, it was built in preparation for (and immediately followed by) construction of the Draper. While small in terms of the number of square feet added to the building, the FCP plays a huge role in building operation since it houses the “beating heart” of the climate-control system for nearly the entire building. With its chiller, boilers, emergency generator, and all the machinery, this important addition keeps staff and visitors alike comfortable and maintains a safe environment for our collections.

As difficult as it must have been to connect all the different galleries above ground, the project underground was an even more arduous process of joining the parts of the buildings above to those below with all manner of tunnels and passages. Only when one looks carefully are the seams that connect one building to another apparent. It is remarkable to see that, in spite of the excavation, the concrete-sawing through thick foundation walls, the core-drilling, and all the extensive construction involved with adding new building to old, it’s relatively seamless how one addition is joined to the next. For Center staffers, it’s easy to forget that “it hasn’t always been this way.”

The Plains Indian Museum freight elevator, for example, has always had two doorways to the main floor: one exiting to our loading dock area (south), and the other opening toward the Plains Indian Museum itself (north). Until the FCP was built, however, there was only one door exiting north from the elevator car at the lower level. If Superman, with his X-ray vision, had looked through the concrete south wall of the elevator shaft, he’d have seen nothing but dirt and rock on the other side. These days, a person can now exit from the south side of the elevator into the maintenance storage area of the FCP.

In connecting new and old, the construction crew excavated, built, sliced, and cut foundation walls where necessary, and even added the door to an existing elevator where no door existed before. For staff, it’s now “been that way long enough,” so that no one even thinks about it as they push the elevator button to access maintenance storage.

The Center’s McCracken Research Library contains some of the earliest concept drawings of the Center. While those early drawings bear little likeness to the current facility, the Center’s “founding fathers” did in fact envision many museums, if not under one roof, at least on one site. They used phrases like “Future Location of This or That Museum.” In other words, the idea that the Center itself would be a living, growing, and changing facility predates the groundbreaking of any of the construction projects that created the building we see today. If and when future additions are added to the mix, they will validate the fact that the Buffalo Bill Center of the West remains so much more than just the sum of its parts—in its collections, and in its facility.

Post 200

Phil Anthony is the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Operating Engineer

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.