Roosevelt’s Presidential Tour of Yellowstone National Park – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2006

Roosevelt’s Presidential Tour of Yellowstone National Park

By Jeremy Johnston

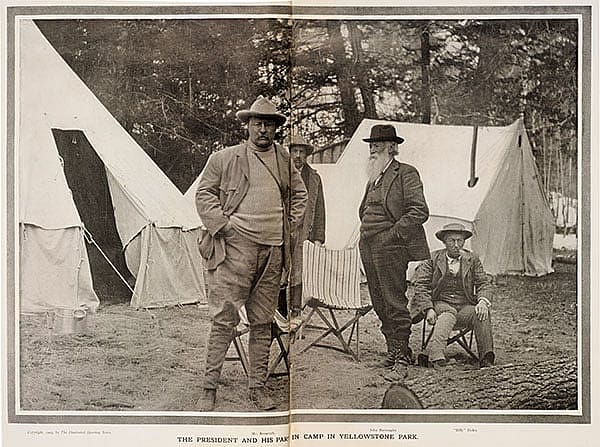

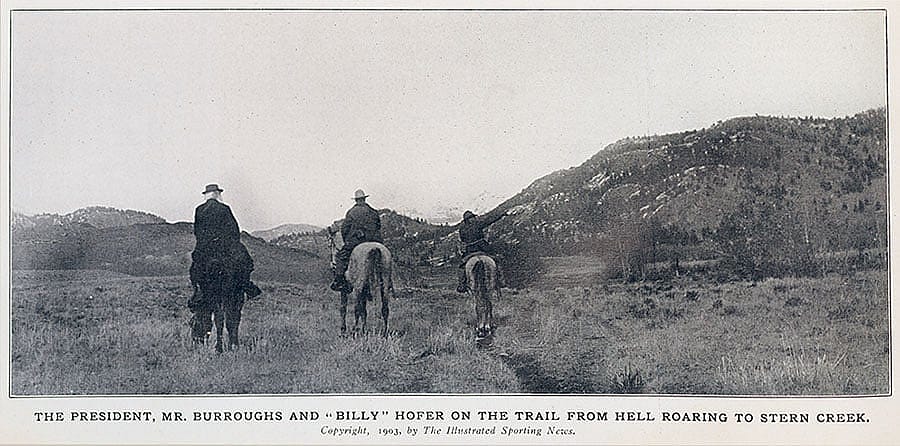

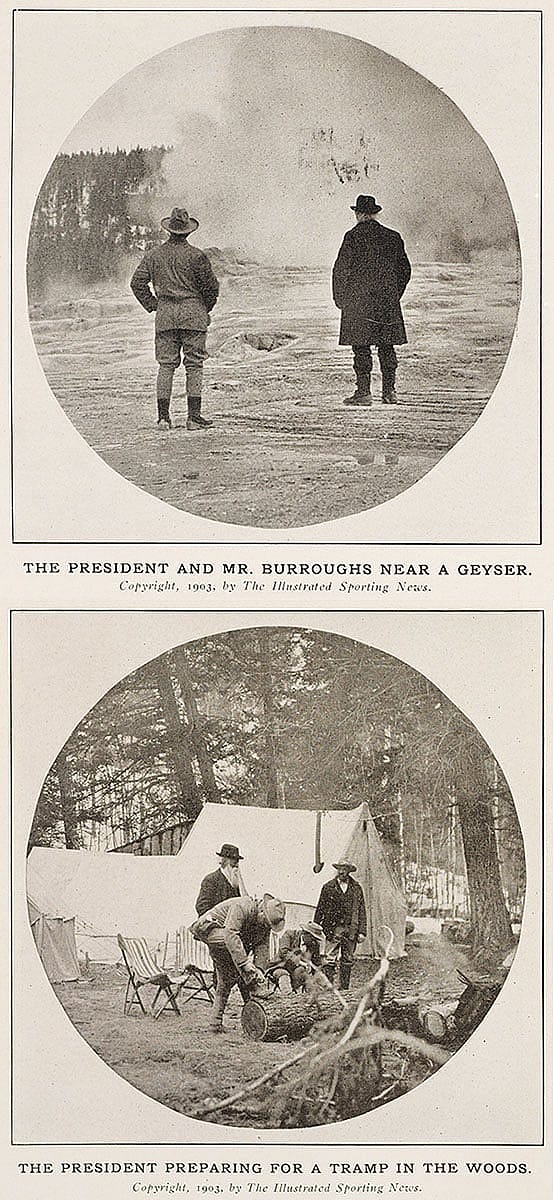

All images are courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt collection at the Harvard College Library.

Although Theodore Roosevelt was the second U.S. President to visit Yellowstone National Park, his two-week vacation marked the most extensive presidential visit in Yellowstone to date. Roosevelt thoroughly explored the Park and, as a result, forever linked his image with Yellowstone’s historic legacy.

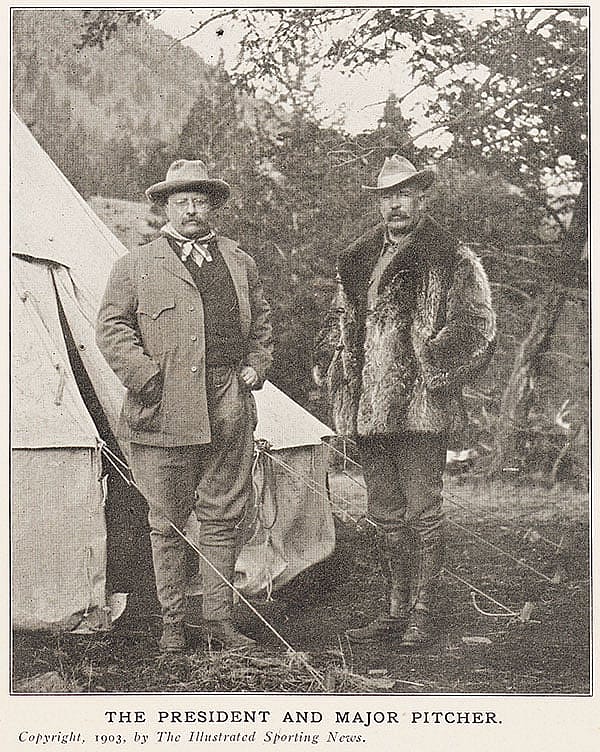

Theodore Roosevelt and his companion, famed naturalist writer John Burroughs, arrived at Gardiner, Montana by train on April 8, 1903. The two men were greeted by their host, acting-superintendent Major John Pitcher. Before they departed for Yellowstone Park, a number of Gardiner’s residents swarmed around the President, while the elderly Burroughs quietly climbed aboard a wagon. When Roosevelt rode off on horseback, leaving Burroughs behind, the eager wagon driver hurried the team along to catch up—unfortunately, with horses running out of control. Burroughs’s wagon forced the Presidential escort off the road. According to his written account of the trip, Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt, Burroughs exclaimed, “This is indeed a novel ride; for once in my life I have sidetracked the President of the United States!”

While Burroughs raced off to the first destination in the Park, Fort Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs, Roosevelt and his entourage observed a variety of wild animals. The apparent tameness of Yellowstone’s wildlife greatly impressed the President, and he attempted a number of times to see how close he could approach various wild creatures. Roosevelt spent his first evening in the Park observing deer on the Fort Yellowstone parade grounds. He wrote his daughter, Ethel, “I wish you could be here and see how tame all the wild creatures are. As I write, a dozen deer have come down to the parade grounds…they are all looking at the bugler, who has begun to play the ‘retreat.'”

The following morning, the presidential party set out for their camp located near the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone River. Burroughs was to remain at the fort until Roosevelt and his entourage established a comfortable camp. To ensure privacy, Major Pitcher sealed off areas where the President would camp to prevent hordes of curious spectators from bothering Roosevelt. One reporter ignored Pitcher’s order and set out, accompanied by his dog, to find Roosevelt’s camp for an exclusive interview. A cavalry patrol caught the reporter, however, shot his dog, and then escorted him outside of the Park boundaries with orders not to return.

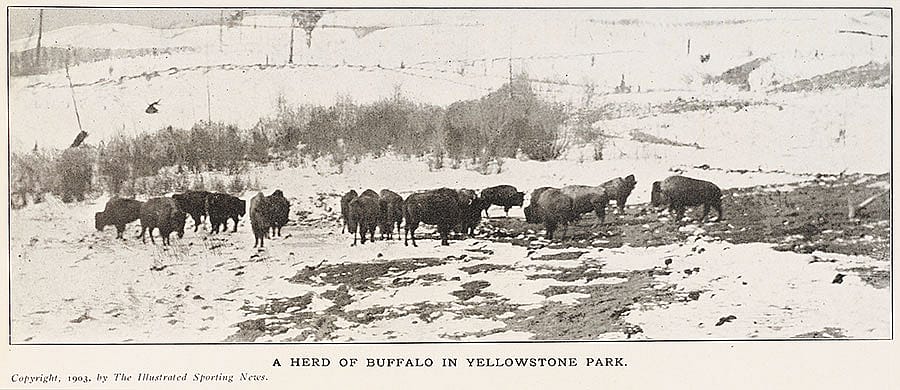

Roosevelt viewed many elk along his way to the first campsite on the Yellowstone River. “They were certainly more numerous than when I was last through the Park twelve years before,” he recalled in his account, “The Wilderness Reserves,” which was reprinted in his book, Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter. In one sitting, the President—with the aid of Pitcher and Elwood Hofer, one of their guides—counted 3,000 head of elk. Roosevelt also noticed many elk carcasses and he paid close attention as to what caused their deaths. Two were killed by scab; some were killed by cougars; but the majority was killed by winter starvation.

Roosevelt did not attempt to kill any predators during his trip through the Park, although he had originally planned to turn this visit into a hunt with his former guide and mountain lion hunter, John B. Goff. Roosevelt decided against hunting in Yellowstone, fearing the non-hunting public and his public opponents would severely criticize him for killing an animal in a federal reserve closed to hunting. Buffalo Jones, a game warden and self-proclaimed friend of Roosevelt, was unaware of the President’s final decision not to hunt. He determined to entertain Roosevelt by taking him to hunt a cougar using a pack of dogs. When the excited Jones reached the camp, Roosevelt quickly ordered both the dogs and Jones back to Fort Yellowstone.

After the fourth day out, Burroughs joined the party and was surprised to find Roosevelt had gone on a hike by himself. Burroughs noted Major Pitcher seemed nervous about his famous guest setting off on his own, but the President was eager to get away by himself to pursue some elk seen the previous day. Roosevelt soon located the elk and spent the day pursuing them for a closer view. After spending an hour observing the elk herd at a range of 50 yards, Roosevelt returned to camp completing an 18-mile hike. Upon his return, he eagerly described all of the animals he viewed on his solitary trip.

The following day, the men broke camp and set out for Slough Creek. Burroughs attempted to fish the stream, but ice prevented him from doing so. Burroughs instead studied bird calls with Roosevelt. After hearing one strange call, the men followed the source of the sound to find a pygmy owl. “I think the President was as pleased as if we had bagged some big game,” Burroughs recorded in his account. “He had never seen the bird before.”

While en route to their next campsite near Tower Falls, Roosevelt spied elk and signaled for Burroughs to follow. Burroughs ambled along at a slow pace due to the rough terrain and lost sight of the President until he climbed over a hill. There he saw the President standing 50 yards from an elk herd. “The President laughed like a boy,” Burroughs recalled. He and Roosevelt then proceeded to a plateau where they could continue to view the elk. “And then the President did an unusual thing,” Burroughs noticed. “He loafed for nearly an hour.”

The next afternoon at their new camp, Roosevelt was shaving when someone informed him a herd of bighorn sheep was approaching. Roosevelt, with his face half covered with shaving soap and a towel draped around his neck, decided to postpone his shave and view the sheep instead. Roosevelt remained oblivious to his comic and half-dressed appearance until Burroughs sent an aid to retrieve the President’s coat and hat.

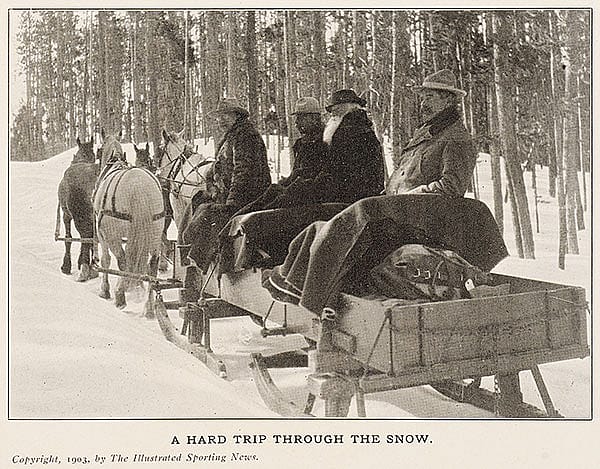

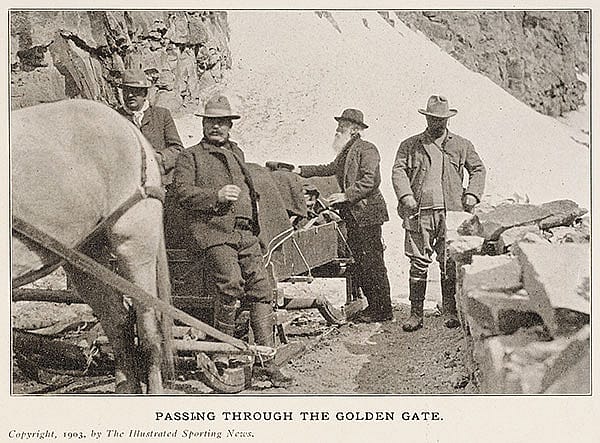

On April 16, the presidential party again packed up the camp and returned to Fort Yellowstone. The day after, Roosevelt, Burroughs, and Pitcher traveled to Yellowstone’s famed geyser basins in a horse-drawn sleigh, accompanied by Park concessionaire Harry Childs. Snow in this area of the Park reached levels ranging from four to five feet in depth; thus, Pitcher ordered the roads to be “cleared and packed.” Roosevelt rode up front with the driver until they encountered a bare patch of ground when Roosevelt and his companions had to walk alongside the sleigh. “Walking at that altitude is no fun,” Burroughs recalled, “especially if you try to keep pace with such a walker as the President is.”

The sleds eventually reached their destination, the Norris Geyser Basin, where the party spent the night at the Norris Hotel. That evening, the President and Burroughs—who shared a single room—decided the room’s temperature was too hot. Roosevelt then opened the window, cooling the room with the fresh night air. The next morning, Burroughs recorded the hotel caretaker’s surprise: “There was the President of the United States sleeping in that room, with the window open to the floor, and not so much as one soldier outside on guard.”

After a cold night’s sleep, the President continued traveling to the Fountain Hotel, located near the Lower Geyser Basin. As they were riding along, Roosevelt suddenly jumped down from the sled and captured a mouse under his hat. While the others went fishing in the heated waters of the Firehole River, Roosevelt skinned the mouse and saved the pelt, erroneously believing he discovered a new species. Burroughs later told this story to a newspaper writer, but after telling the anecdote, a disturbing thought occurred to him. “Suppose [the writer] changes that u to an o and makes the President capture a moose,” pondered Burroughs. “What a pickle I shall be in!”

From the Fountain Hotel, Roosevelt traveled to the Upper Geyser Basin where he watched the eruption of Yellowstone’s most famous geyser, Old Faithful. Unfortunately, Roosevelt did not record his opinions of any of Yellowstone’s geysers in his account. Burroughs, however, felt the geysers were a waste of energy. “One disliked to see so much good steam and hot water going to waste; whole towns might be warmed by them, and big wheels made to go round,” Burroughs recalled. “I wondered that they had not piped them into the big hotels which they opened for us, and which were warmed by wood fires.”

After viewing the famous geysers in the Upper Geyser Basin, Roosevelt returned to the Norris Hotel for another night’s stay. Unfortunately, upon their return, tragedy struck the presidential party. The sleigh driver, George Marvin, died suddenly of a heart attack. Burroughs mourned his passing and praised the man’s skills as a sleigh driver. He also recalled Roosevelt hurrying to the barn, where Marvin’s corpse lay, to pay his last respects to the man. When he returned to Mammoth, Roosevelt looked up Marvin’s fiancée to express his sympathy.

Roosevelt and his colleagues worked their way from Norris Geyser Basin to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Beginning from the Canyon Hotel, Roosevelt and Burroughs strapped on skis and proceeded over shoveled paths to scenic vistas of the Canyon. Burroughs believed this to be the grandest spectacle of the entire Park. An ice bridge spanning the brink of the falls fascinated him, especially when he learned coyotes traversed this precarious crossing. After he viewed the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, Roosevelt visited with a squadron of soldiers in their winter quarters and inquired about their tour of duty guarding Yellowstone National Park. Roosevelt and Burroughs later enjoyed downhill skiing on the low hills near the Canyon Hotel. In their merriment, Roosevelt tumbled into the snow causing Burroughs to laughingly remark about the “downfall of the administration.”

As the trip ended, Roosevelt returned to Mammoth Hot Springs, where he agreed to speak at the Masonic cornerstone-laying ceremony for the future archway located at the northern entrance to Yellowstone, which would later bear his name. In his speech dedicating the arch, Roosevelt praised Yellowstone. “The geysers, the extraordinary hot springs, the lakes, the mountains, the canyons, and cataracts unite to make this region something not wholly to be paralleled elsewhere on the globe,” Roosevelt proclaimed. “It must be kept for the benefit and enjoyment of all of us.”

Ed. note: At the time this article was first published, Jeremy Johnston was a professor of history at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming. He is now the Hal & Naoma Tate Endowed Chair and Curator Western American History; the Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum, as well as the Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody. Johnston earned his doctorate from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2017.

Jeremy Johnston is a descendant of John B. Goff, the Roosevelt hunting guide who was to have helped President Teddy Roosevelt pursue a few mountain lions on his Yellowstone Park vacation. In 1905, Roosevelt arranged for Goff to replace Buffalo Jones as game warden in Yellowstone. “I grew up listening to family tales of Goff and Roosevelt,” Johnston explained. “Naturally, this contributed to my great interest in western history and I managed to establish a professional career in the field. So in many ways, this story is a reflection of both my personal and professional interests.”

The photographs of the expedition were taken by Major John Pitcher during the trip. “Due to Pitcher’s orders to isolate the public and newspaper writers away from the president, these photos offer a rare informal perspective of the visit,” Johnston said. “The photos were printed in Illustrated Sporting News in 1903, a short-lived sporting periodical. According to a letter in the Theodore Roosevelt collection at the Harvard College Library, copies of the photos were distributed to each member of the President’s party and then the negatives were destroyed. A few of the images have been reprinted since; however, the majority still have not been seen since the article covering Roosevelt’s trip appeared in Illustrated Sporting News over one-hundred years ago.” Johnston wrote an article about the photographs themselves for Yellowstone Science.

While a graduate student at the University of Wyoming, Johnston wrote his master’s thesis titled, “Presidential Preservation: Theodore Roosevelt and Yellowstone National Park.” Johnston continues to research Theodore Roosevelt’s connections to Yellowstone and the West as he writes and speaks about Wyoming and the American West.

Post 204

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.