Tips from Our Conservator – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2010

Don’t Lather That Leather: Tips from Our Conservator

By Beverly Nadeen Perkins

With hunting season virtually past, it’s time to treat—or not—leather tack, saddles, scabbards, and the like, and to decide how best to store leather materials until next spring. But, in the museum setting, leather may be treated in an entirely different manner. Buffalo Bill Center of the West Conservator Beverly Perkins tells how treatment and storage of leather in a museum collection is often in contrast with how leather objects are handled at home.

Years ago, a donor came to the front door of the Center of the West sitting on his donation. The beautiful presentation saddle was sandwiched between the rump of the horse and the rump of the donor. There was much fanfare over this important donation. The museum staff accepted the donation wearing white gloves and gently placed the saddle on a padded cart. (Read more in this Treasures blog post.)

This story illustrates an interesting dilemma facing museums: Many objects found in museum collections are similar to those still in use in home kitchens, garages, or workplaces. People generally understand that objects in a museum are not handled in the same manner as those they live with out in the “real” world. Surely, they’d be horrified if museums placed a Ming vase in the dishwasher or drove sculptures through the car wash. The general public even has a sense that sending the family Ottoman carpet to the dry cleaner may not be the best course of action.

Works of art such as paintings are always given special treatment whether they are hanging in the living room or the art gallery. In other words, it is common practice for individuals to apply museum standards to the care of paintings and fine drawings. That is not always the case for other cherished objects.

Materials such as guns and leather are usually passed down to the next generation with specific, and often personal, methods of care. When your grandfather’s grandfather passes down his secrets for keeping leather supple and firearms in good working order, these guidelines are retained and shared with the utmost respect and authority. This type of information was invaluable for the success of your ancestor’s survival, and it’s still vital information to pass on today.

To feed or not to feed: leather

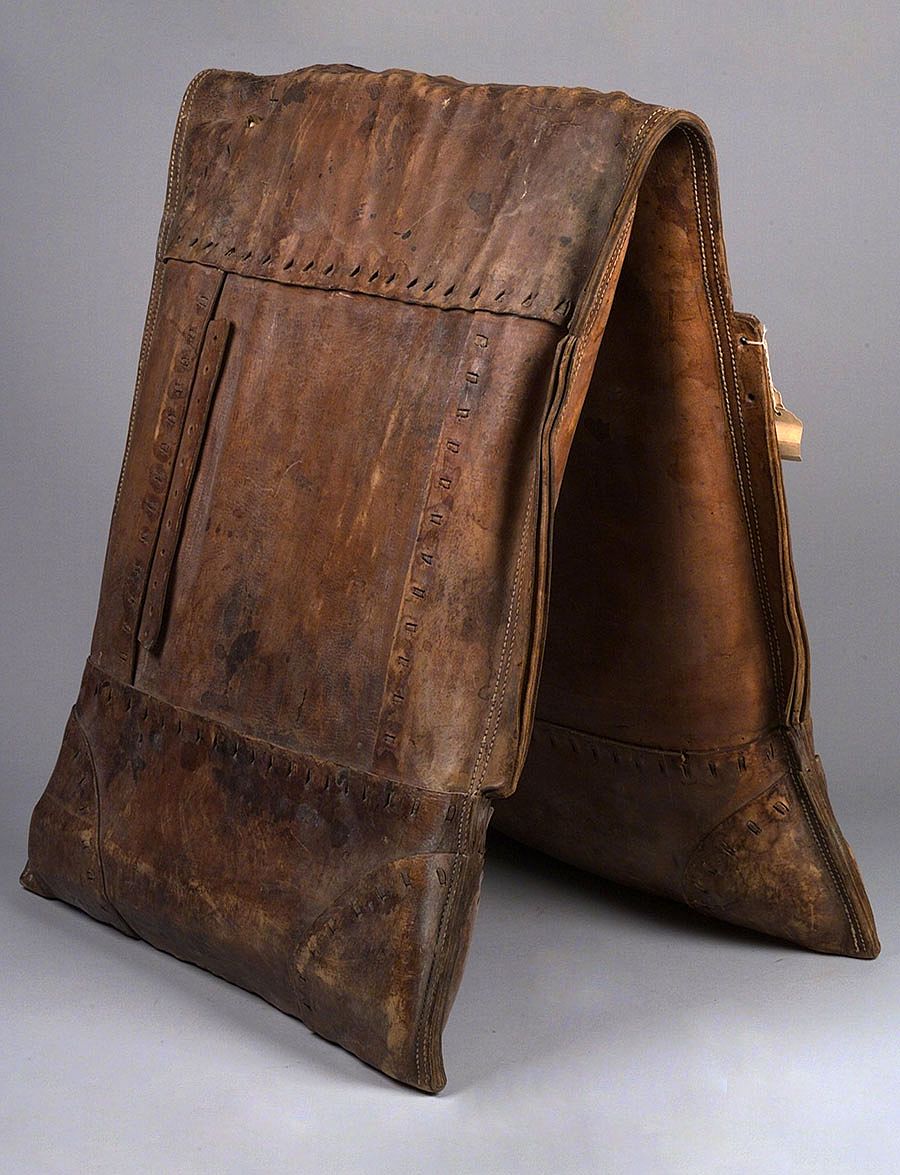

As far as leather is concerned, there are fundamental differences between the leather used on a horse or foot, and the leather of horse tack or boots in a museum collection. The leather used to restrain a horse or protect your feet must remain supple, withstand strenuous cleaning, and be impervious to the elements. The leather in a museum should be in a stable environment with minimal changes in temperature and relative humidity, and with low light levels. There’s no longer a need for the leather to remain supple. It needs only to remain flexible in order to gently move it or place it on a mount.

Instead of “feeding” leather to protect it, museums exhibit and store leather in a stable environment where it will remain clean and suffer minimal exposure to large amounts of light and wide swings in relative humidity or temperature. Museums don’t use leather dressings, oils, waxes, or silicone oils on leather; these materials aren’t needed in a stable environment. If used, these substances would eventually break down, and become dirty and difficult to remove.

Some visitors to museums are troubled by a white “bloom” they see on leather such as shoes, saddles, and tack. They’ll often alert staff that they’ve seen mold on the leather displayed in exhibits. This white matter is generally not mold but old leather dressing that is breaking down. It could also be evidence of past use, such as residual salt from horse sweat.

What is that “bloomin'” stuff?

If you want to determine the nature of the bloom, use magnification such as a head loupe, strong reading glasses, or a magnifying glass. If it is mold, it will have some dimension to it, like broccoli—not like a flat drawing of broccoli. If it is active mold, it will smear when touched with a tiny artist’s brush; an inactive mold will powder and blow away when touched with the brush. If the substance doesn’t smear or powder, it’s probably not mold.

Once you have determined the bloom isn’t mold, you may try to reduce its appearance. Warm air from a hair dryer (not a heat gun) can reform the bloom material. Then, you can use a soft, cotton rag to gently remove it. It’s likely that this bloom will become visible again if the object is placed back into a cool or cold room. Repeat warming and wiping if the bloom reappears.

You can clean leather best by brushing it with a clean, dry brush. If there is a great deal of dust to remove, hold the nozzle of a vacuum cleaner in one hand and brush the dust in the direction of the vacuum nozzle. You can use a soft, dry cotton rag cut from an old t-shirt to wipe off light dirt. The use of water and/or solvents is not recommended for the cleaning of leather.

The rest of the story

You should monitor your leather objects every few months to check for insect activity. If you suspect insect activity, place the object in a plastic bag to more easily keep an eye on the piece to see if there are insects or vermin present. If so, you may need to place the piece in a freezer. At this point, it is best to call your local conservator for more information.

If at all possible, do not fold objects. If there is a fold, pad it with a small amount of tissue or unbleached cotton formed into a roll. Don’t place leather and other textiles on forms or mannequins that are too large. It’s better to underpad an object rather than to overstuff the form. Leather should not be hung from metal hangars or nails; padded surfaces and slanting mounts are a better way to show and store objects. To reduce permanent creases, take the time every year to unfold your object and refold it in a different way. Finally, leather shouldn’t remain on display for more than a few months at a time. When removed from view, place your leather objects in dark storage.

You can find more information about the care of leather through the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works at www.conservation-us.org.

Beverly Perkins is the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s conservator. She holds both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in art history along with a master’s degree in art conservation from the Cooperstown Conservation Program at the State University College at Buffalo, New York. She has expertise in ceramics, wood, metal, glass, leather, feathers, plant fibers, taxidermy, painted surfaces, bone, and ivory. Before arriving at the Center in 2008, she was the Western Field Service Officer for the Balboa Art Conservation Center in San Diego, California.

Post 205

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.