On the heels of Lewis and Clark – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2009

On the heels of Lewis and Clark: Charles Fritz follows the inspiring visions of western artist-explorers

By Christine C. Brindza

Former Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

The work we are now doing is, I trust, done for posterity, in such a way that they need not repeat it. We shall delineate with correctness the great arteries of this great country: those who come after us will…fill up the canvas we begin. —Thomas Jefferson, May 25, 1805

It was the desire of artist Charles Fritz to fulfill the wish of Jefferson, and he adopted these words as his personal mission. The culmination of this effort was a temporary special exhibition at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in 2009. Here’s a look back at Fritz’s work for that exhibition, An Artist with the Corps of Discovery: One Hundred Paintings Illustrating the Journals of Lewis and Clark.

When Fritz took on the monumental task of illustrating the journals of Captains Lewis and Clark and their Corps of Discovery (1804–1806), he looked to artist-explorers and their works of art from their travels into the “far West,” the land beyond St. Louis, Missouri. These artists explored the uncharted and newly acquired Louisiana Territory and documented what they saw in various art forms. Though separated from the Lewis and Clark expedition by decades, these artist-explorers often saw the same sites and indigenous cultures of the land. They were among the first to depict the wildlife, the topography, and the people of the region.

The artist-explorers

Karl Bodmer, Carl Wimar, George Catlin, William Jacob Hays Sr., John Mix Stanley, and other early nineteenth-century artists ventured into the lands surrounding the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. They pursued personal or patron interests, or commissions from businesses or government entities. The artists were needed to document the West, as no other imagery existed at the time. When these artists returned from their explorations, the public saw their drawings, paintings, and prints, satisfying curiosities and spurring on imaginations about the great western frontier.

On their heels, though roughly 150–200 years later, Fritz follows his roots as an artist, rendering the same landmarks, but portraying his own experiences of the rich history and landscape of the Rocky Mountain West. He conducted extensive research about the journals of Lewis and Clark, the people they met, and the places they visited. Fritz traveled along the route of the Corps of Discovery at least twice, capturing what natural sites still existed the same way that Lewis and Clark viewed them. Many waterfalls and rivers had long been dammed, and towns had sprung from uninhabited lands and early settlements. However, Fritz had access to the works of artist-explorers to see “through their eyes.”

The Missouri River served as the primary thoroughfare into the northern Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. It is the longest river in the United States, spanning the country from St. Louis, Missouri, to western Montana. This river defined the boundary of the American frontier in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. St. Louis would eventually mark the beginning point for various migratory crossings, such as the Oregon and Santa Fe trails in years to come. Railroads originated along this river, often commissioning artists to portray the extraordinary sites for mapping potential routes.

Karl Bodmer’s two-year trip through North America

At the time of Karl Bodmer’s explorations in the 1830s, the Missouri River was still wild and the land around it uncultivated. Not only did Bodmer travel into the “uncharted” West, but also recorded the landscape, clothing, ornamentation, and traditions of the Indian peoples he and his patron, Prince Maximilian of Pied, encountered during their twenty-eight-month trip throughout North America. Fritz carefully examined these artistic documents and incorporated parts of them into his paintings. Not many native artifacts remain from the early-to-mid 1800s, so Bodmer’s renderings are among the most reliable in terms of historical accuracy.

Prince Maximilian and Bodmer traveled from Germany with the purpose of documenting the search of the “natural countenance of North America.” Bodmer, a young, successful landscape painter, found the opportunity an adventure of a lifetime. Among his requirements for taking the trip was to convey the plants, animals, and peoples with the greatest possible accuracy. Maximilian, who believed the Native peoples that inhabited North America were going to disappear, later published the works of art created on this journey. To the prince, Bodmer recorded civilizations on the verge of extinction.

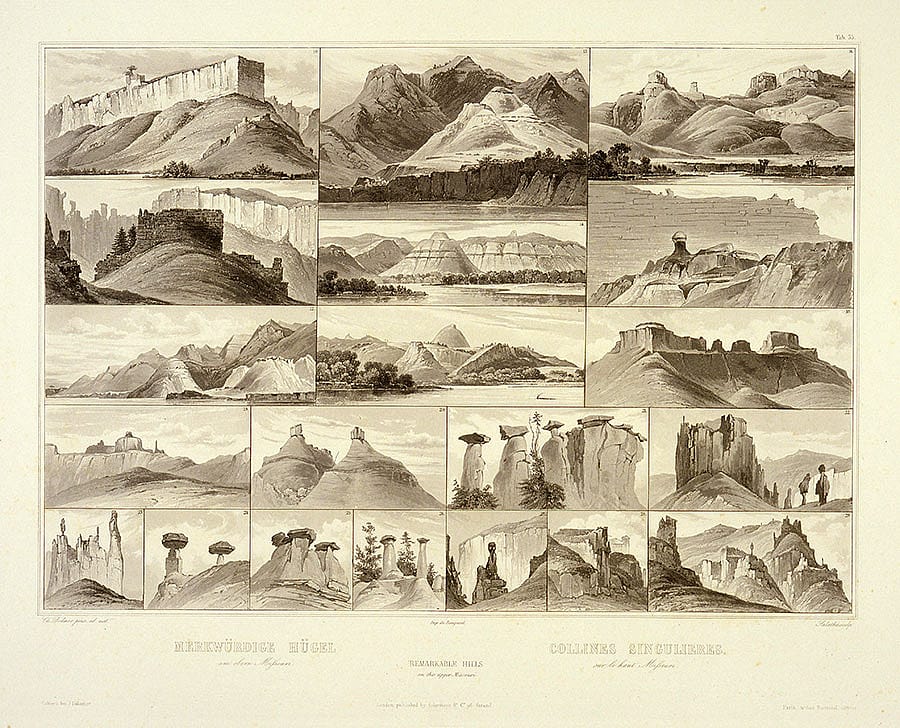

Bodmer was not only intrigued by the people of the West, but with western landscapes as well. After viewing the White Cliffs of the Missouri River, Bodmer created several depictions, including Remarkable Hills on the Upper Missouri. Bodmer also came to the junction of the Yellowstone and the Missouri Rivers and had to capture the grand vistas of the landscape, filled with abundant wildlife and plant life. In his Junction of the Yellow Stone River with the Missouri, he attempted to convey the awesome space, mountains, and expansive rivers. Though he may have romanticized the scene slightly, it is thought to be an accurate representation of how it looked in the 1830s.

Fritz visited the White Cliffs and the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers as part of his journey along the route of Lewis and Clark. He was enchanted by the sunlight’s effect on the cliffs and painted their brilliance in works like Canoes at White Cliffs. In his version of the river junction, The River Rochejhone—April 25, 1804, he placed a delighted Lewis and Clark at the forefront bluffs of the Rochejhone (Yellowstone) River at its confluence with the Missouri. The attention is not on the broad landscape, but the unique geology of the land.

Bodmer paid particular attention to the dress and adornments of the Indian people he encountered while on his journey along the Missouri. In his Missouri Indian, Oto Indian, Chief of the Poncas, for example, he brings awareness to the distinctive dress of these men. Fritz examined such details from Bodmer’s work and incorporated them into his portrayals of Indians. The clothing of the Missouri people in his Addressing the Oto and Missouri at Council Bluffs—August 3, 1804, derived partially from Bodmer’s work.

And there were others…

There were other artists who served as explorers of the great Missouri River. Carl Wimar, a German-American artist, witnessed the “far West” firsthand. He became one of the last artists to depict the Indians and the landscape as Lewis and Clark would have recognized them. Living in St. Louis beginning in the mid-1840s, he took multiple trips along the Missouri by steamboat. In 1858 and 1859, he journeyed almost 2,500 miles upriver, gaining access to Indians and landscapes, which he drew in sketchbooks. With the onset of the American Civil War, the westward migration of Anglo-Americans, and the reservation period to come, the West would never be the same. Wimar conveyed what he saw along the wide Missouri, recording the geography as he traveled.

Wimar’s work includes significant depictions of the American frontier, revealing both mythical and truthful conceptions of the region. Fritz, while compiling his research for the Lewis and Clark series, discovered a Wimar sketchbook in an archive and knew he’d struck gold. Though Fritz’s style is more realistic than Wimar’s more romantic and theatrical one, as seen with On Pursuit, Fritz strongly referenced Wimar’s sketch of the Missouri River in Midday View Over the Big Bend because of the distinctive features the artist-explorer had drawn. Today, Big Bend is a large reservoir, much different than its view in 1804. It was only natural that Fritz looked to the work of an artist-explorer for historical accuracy.

Though he was not directly influenced by the work of George Catlin, Fritz did carry on the conventions of this artist-explorer. Catlin’s mission was to chronicle the West in the early 1830s from an anthropological perspective. According to Catlin, his task was to paint “faithful portraits of their principal personages, both men and women, from each tribe…and [to keep] full notes on their character and history…for the instruction of all ages.”

Catlin heard of Lewis and Clark’s adventures into the North American continent and was captivated by them. The artist actually sought out the expertise of William Clark, who was the Superintendent of Indian Affairs and Governor of the Missouri Territory at the time, about his impressions of the Indians.

During his visit in the 1830s, Catlin was especially enamored with the Mandan Indians, capturing their customs, ceremonies, living habits, and their portraits in paintings. Unfortunately, these people suffered from smallpox and other deadly epidemics, nearly decimating them. These depictions from their way of life remain for historians and artists alike to study. Though his style is naïve, Catlin’s images are counted among the best representations of Native American tribes of that period.

During the winter of 1804–1805, the Corps of Discovery saw the Mandan’s living quarters and recorded their appreciation for them. Years later, Catlin discovered these fascinating structures as well, and considered the earth lodge a center of Mandan culture. Catlin’s The Last Race, Mandan records a major religious ceremony, the O-kee-pa, which was a test of manhood and a fertility rite. He found the circular, earth-covered lodges of the Mandan people very pleasing and included them in several of his works. Though Fritz did not paint a ceremony such as this, as one was not recorded in the journals of the Corps, he did represent a traditional Mandan village of the period. In Nightfall in a Mandan Village, true to entries in the journals, he depicted a wintry evening when the Mandan people brought their best horses into stalls inside the lodges to keep them safe, an essential part of Mandan life.

Fritz relied on historical documentation, art history, and his own imagination in his Lewis and Clark series. He created history paintings from a contemporary perspective, looking back on these historic events. The magnificent herds of bison, for example, are no longer rulers of the Plains. The destruction of bison is viewed much differently now than in the nineteenth century. Fritz could not accurately render from experience what artist William Jacob Hays Sr. encountered when he descended the Missouri River. Hays’s Herd of Bison Crossing the Missouri, painted in 1863, is the result of numerous field studies created while he took a steamboat trip along the Missouri three years prior.

After returning from his voyage west to his home in New York, Hays—known as a painter of animals—could not resist depicting the Herd of Bison Crossing the Missouri. He conveyed a grand landscape from a high vantage point, showing brilliant sunlight on the river, just as Fritz does in his work The Ancient River. As a painter that follows in the tradition of the Impressionists and their philosophy of capturing natural light, Fritz also pays homage to artists such as Hays in his romantic rendition of the Missouri.

Though the Missouri River was still considered the “far West,” it was not the farthest point reached by explorers and artist-explorers of the nineteenth century. In their journey to the Pacific, Lewis and Clark traveled past the headwaters of the Missouri River, taking notes on specific landmarks and geographical features along the way. As the Corps of Discovery moved closer to the Pacific Ocean, they relied on the Columbia River, the largest waterway in the Pacific Northwest. It stretches from today’s British Columbia through Washington state before emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

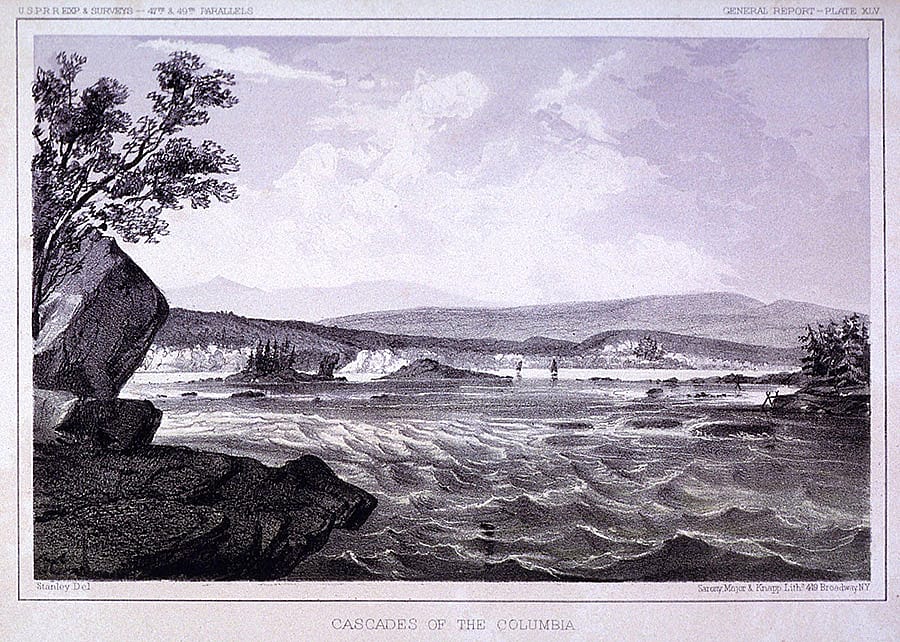

John Mix Stanley embarked on a challenging thousand-mile journey down the Columbia River in 1847, reaching what was then known as the Oregon Territory. Although there were Anglo-American settlements emerging as a result of Oregon Trail migration, overall, the landscape had not changed too dramatically since the Corps of Discovery’s travels. Stanley created illustrations for the United States publication Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economic Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, a twelve-volume series published between 1855 and 1861. Stanley embraced a newer, more progressive doctrine of the time that needed the expertise of artist-explorers: the Westward expansion of “civilization.” However, he believed that the Plains Indian tribes would eventually be pushed to the end of the continent and destroyed. He undertook the same mission as Bodmer and Catlin: to paint the Indian people and their societies before they were gone forever.

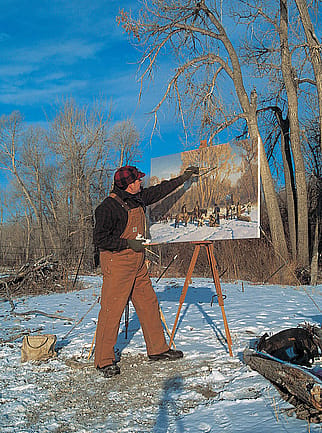

In the twenty-first century, Fritz visited the great Columbia River and painted several versions of it for his Lewis and Clark series. The journals of the Corps of Discovery mention the raging rapids and dangerous falls they encountered as they attempted to reach the Pacific Ocean faster. The Columbia, an immense and powerful waterway, was yet to be tamed in 1805, but Fritz was determined to portray the falls and rapids as accurately as possible. He concentrated on the journal entries and set up his easel along the shores of the Columbia River, analyzing the time of day, weather conditions, locations, and other specifications mentioned in the journals. His Descending the Grand Falls of the Columbia is a faithful depiction of the perils the Corps of Discovery constantly faced along the Columbia River.

More than 150 years before Fritz held brush to canvas, John Mix Stanley traveled the Columbia River and executed images such as Cascades of the Columbia. Stanley, an adventurer, canoed down the river, just as Lewis and Clark had decades before. He viewed other interesting landmarks, such as the volcanic peak of Mount Hood in northern Oregon, a sight the Corps beheld with awe and wonder. Fritz’s Headwinds on the Columbia and The Wishram Land at Sunrise show how he took on the challenge of illustrating these key places.

The land of the Corps today

The creations of these artist-explorers shaped public perceptions of the West, from as early as the 1830s through today. Our ideas of how people of that era lived, as well as the distinctive features of the land, were formed from viewing the artwork of those artists who traveled there. Fritz, an artist of today, experienced a West unimaginable to the artist-explorers of the nineteenth century. He traveled the route of Lewis and Clark and artist-explorers by automobile, rather than by foot, horse, keelboat, or steamboat. The great Missouri and Columbia Rivers are now controlled by dams and traveled by fuel-powered boats or crossed by steel bridges.

Charles Fritz succeeds in his personal mission to “fill the canvas…,” adopted from Thomas Jefferson. He took this charge literally and figuratively, continuing the task started by the great artist-explorers of the North American continent. He is grateful to these travelers of the grand Missouri and Columbia rivers, using their images to support his own twenty-first century views of the “far West” of Lewis and Clark. Though there are drastic differences between the work of Fritz and artist-explorers Karl Bodmer, Carl Wimar, George Catlin, William Jacob Hays, and John Mix Stanley, the overall messages are similar: Capture for posterity a time and a place important to American history. In this extraordinary effort, Fritz has continued the tradition of the artist-explorers.

Post 208

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.