!["A new scout on the old trail" with "Davy Crockett, Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack [Omohundro], Kit Carson, California Joe, [and] Dan'l Boone," June 5, 1912. LC-DIG-ppmsca-27847](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=800,height=553,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PW213_Puck4-LC-DIG-ppmsca-27847.jpg)

Wit Larded with Malice*: The Satire of “Puck” Magazine – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2015

Wit Larded with Malice*: The Satire of Puck Magazine

*Quote from Shakespeare about satire. Unless otherwise noted, all images are from Puck magazine, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540, USA

By Marguerite House

Media Coordinator

As men neither fear nor respect what has been made contemptible, all honor to him who makes oppression laughable as well as detestable. Armies cannot protect it then; and walls which have remained impenetrable to cannon have fallen before a roar of laughter or a hiss of contempt. —Edwin Percy Whipple (1819–1886), American essayist and critic

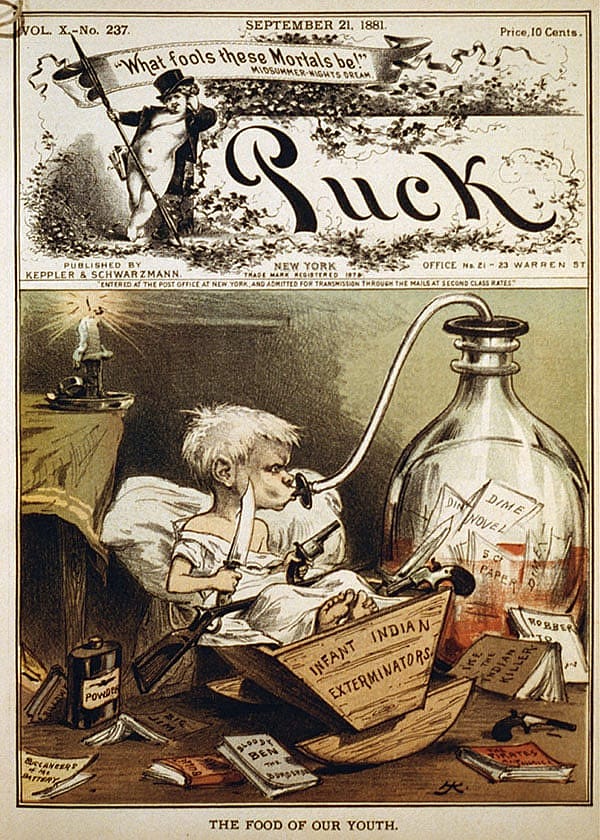

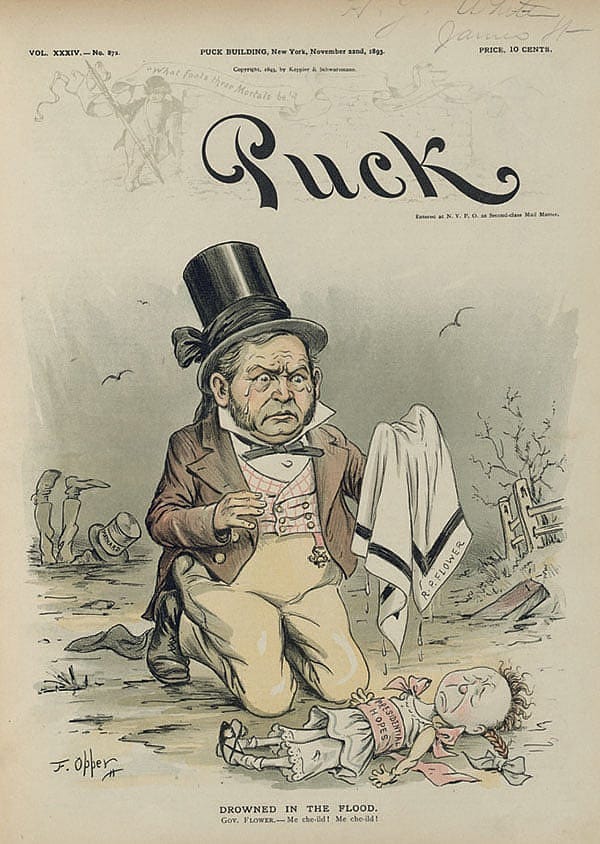

From the English Punch magazine of the mid-1800s to the Harvard Lampoon, Mad magazine, New Yorker, and the Web’s Onion, satire has served the dual purposes of humor and making a point. Poking fun at public policy, society, culture, or politicians is downright amusing—especially from those who do it well. One of the most successful such publications was Puck magazine (1871–1918). Points West readers, as well as visitors to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, have seen Puck a time or two.

Joseph Keppler was a master of satire and not much missed his pen. In 1876, he and his partners created Puck magazine as a German-language publication for German immigrants to America. They named it “Puck” after the mischievous prankster of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and employed one of Puck‘s lines from the play as the magazine’s motto, “What fools these mortals be!” Keppler based the caricature of Puck in each issue on his 2-year-old daughter.

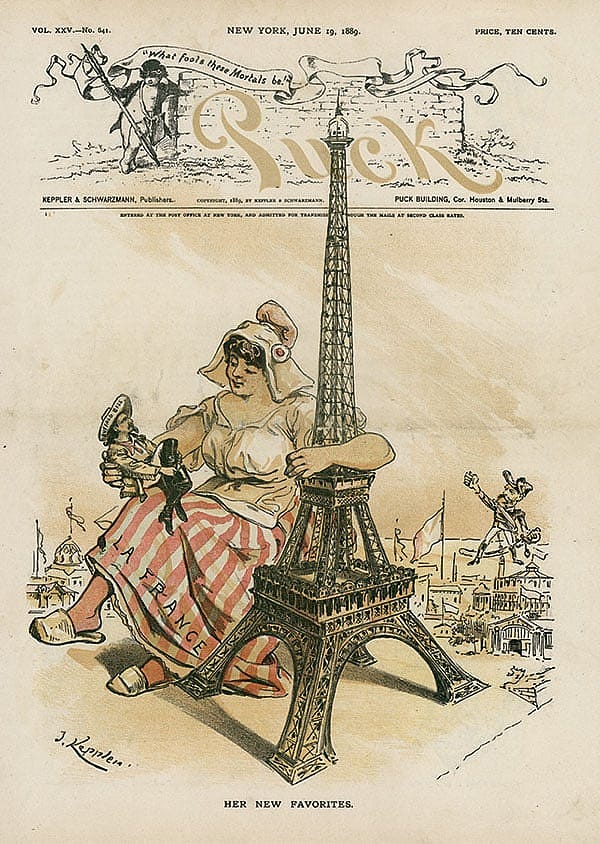

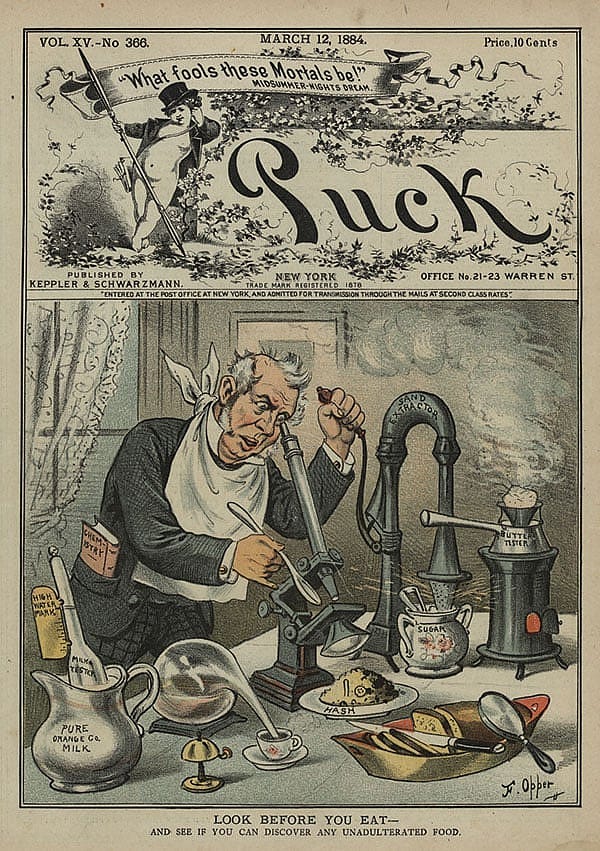

From a technical standpoint, Puck was different than other magazines of the day. It used lithography rather than wood engraving for printing and sported three cartoons rather than the traditional, single drawing. Once it began printing an English edition in 1877—and was the first American magazine printed in color—it became a major competitor of the other news magazines in production at the time. Neither did it hurt that Puck cost 10¢ at the newsstand, while the popular Harper’s Weekly, for instance, sold for 35¢ per copy. At its zenith, Puck had 125,000 subscribers during the 1884 presidential campaign.

!["A new scout on the old trail" with "Davy Crockett, Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack [Omohundro], Kit Carson, California Joe, [and] Dan'l Boone," June 5, 1912. LC-DIG-ppmsca-27847](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=900,height=622,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PW213_Puck4-LC-DIG-ppmsca-27847.jpg)

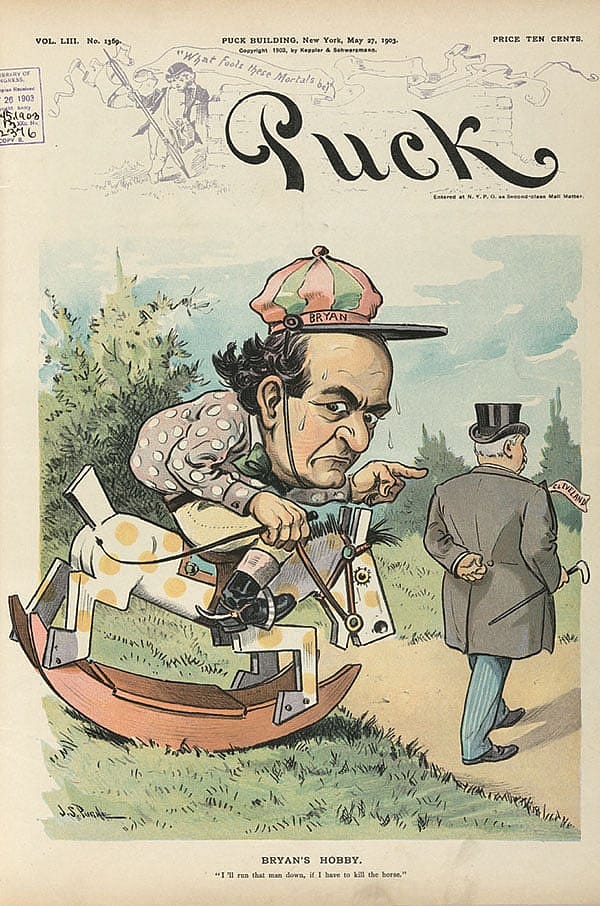

From a content standpoint, Keppler and crew embraced American politics, culture, economics, and social issues, using the mascot Puck as the mouthpiece for the magazine’s comments. They tackled everything from the pope to Tammany Hall, Republicans and Democrats to women—and yes, even Buffalo Bill. Puck cast the homesteader as a scarecrow Trojan horse; John Sherman (senator and presidential candidate from Ohio) as a knife grinder; Teddy Roosevelt as a raven cackling “Nevermore” above President Taft; U.S. Grant as a baby being force fed by his advisors; Joseph Pulitzer as a street musician and a jester (he countered by trying to buy Puck); and William Jennings Bryan as a jockey on a rocking, a.k.a. hobby, horse.

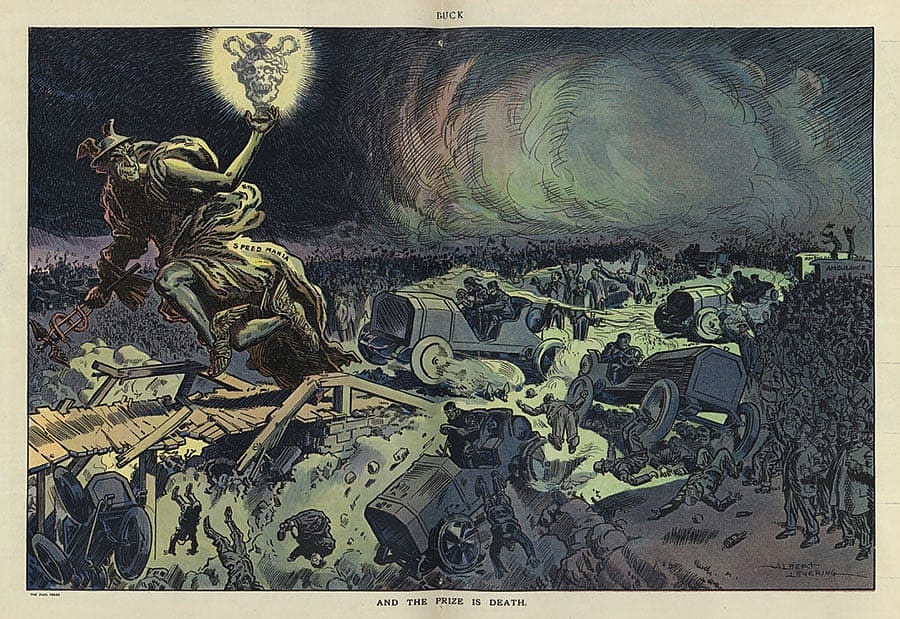

While the issues themselves may be lost on today’s readers, it’s hard to deny that Puck‘s garish cartoons can be downright knee-slappers. Plus, those colorful images paved the way for other publications to draw on color to grab the reader’s attention.

But some of Puck‘s cartoons are timeless, like the one titled, “Preserve Your Forests From Destruction And Protect Your Country From Floods And Drought” in the 1884 issue when Yellowstone National Park—the first national park—was still a pre-teen at twelve years old.

Indeed, there are numerous Puck illustrations that encompass those themes that continue to strike a nerve these many years later. Take a look at the images herein for examples of those which are still relevant today.

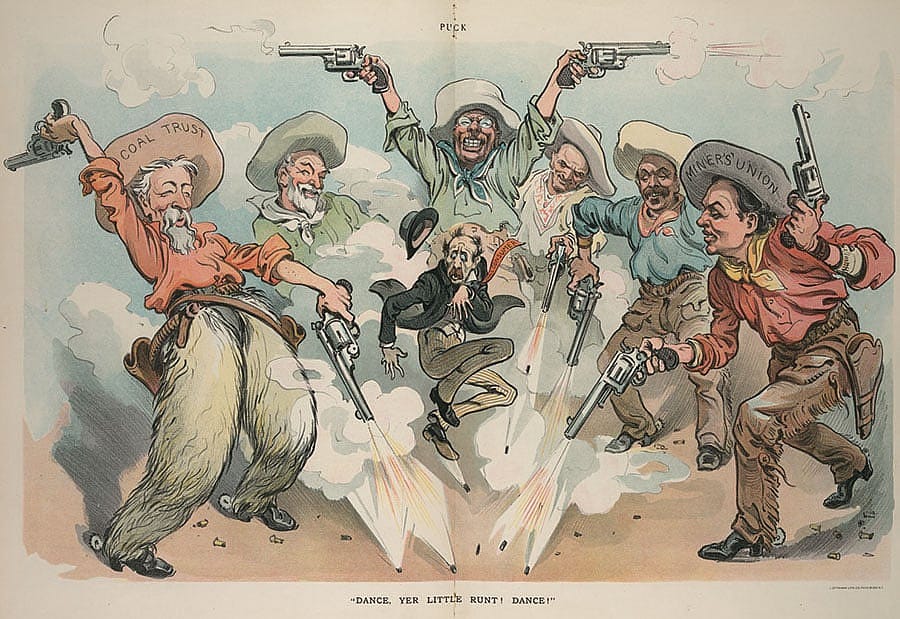

A periodic subject in Puck was the West and everything associated with it. From Native Americans to cowboys, the magazine often appropriated the West’s issues and icons for its satire. For example, with the “Dummy Homesteader or The Winning of the West,” November 24, 1909, Puck decries the corruption associated with claims to public lands. In “Dance, yer little runt! Dance,” cowboys (coal trust and miners’ union) fire shots at the lowly, suffering consumer while Teddy Roosevelt joins the fray with his six-shooters.

One of Puck‘s favorite subjects was President Taft whom the magazine often portrayed with all things western, too—the clothes, the hat, the horse. He’s “Winning the West” with a campaign tour to meet his would-be constituents, and all his gear is tagged with “TR,” Teddy Roosevelt’s initials, implying Roosevelt’s endorsement in the coming 1912 election.

After Taft lost the election, Puck pictures him as a cowboy tossed from his mount, looking considerably worse for the wear, and lamenting, “The Tenderfoot—Ride the beast if you want to. I’m through. Me for a more restful seat.” The invitation next to him says, “Dear William, Come over and have a seat in my Kent Chair of Law. Yours—Yale,” a reference to the position he subsequently accepted at Yale, although he joked that “a sofa of law would fit him better.”

In a comment apparently directed at a mediocre satirist, English aristocrat and writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) dissected the essence of satire:

Satire should, like a polished razor keen,

Wound with a touch that’s scarcely felt or seen.

Thine is an oyster knife that hacks and hews;

The rage but not the talent to abuse.

For more than forty years, the successful Puck appeared to have Lady Montagu’s keen razor edge, but what eventually led to its demise? Richard West, author of the 1988 book Satire on Stone: The Political Cartoons of Joseph Keppler, noted in an interview that, at the time, “Puck had the stage largely to itself, but with the advent of four-color printing and lavish Sunday newspaper editions, not to mention the comic strip, the magazine lost its franchise. Also, with the advent of mass marketing in the 1890s, its format did not lend itself to advertising, and its emphasis on partisan politics scared some advertisers away.”

Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst purchased Puck in 1916 and published it for two more years before the magazine folded on September 5, 1918.

Find out more about the Puck magazine online collection at the Library of Congress with its blog “Picture This” here. In his December 20, 2012, post titled “Puck Cartoons: ‘Launched at Last!’,” Woody Woodis, Cataloging Specialist with the Library’s Prints & Photographs, shares his two-year adventure with Puck, digitizing and cataloging some 2,500 images from issues dated 1882–1915.

About the author

Marguerite House has served as editor of Points West since January 2005. She is the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Acting Director of Public Relations. Since 1999, she has also penned a weekly, general subject column for the Cody Enterprise titled “On the House.”

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.