![(Fig. 1, L–R) Note the various locales providing plant materials used in these baskets. NA.106.800, split yucca (Pueblo, southwest U.S., ca. 1930). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harris A. Thompson. | NA.106.463, cedar (Salish, Pacific Northwest, ca. 1900). | NA.106.464, birch (Ojibway [Chippewa], Great Lakes and southeast Canada, ca. 1920). | NA.106.597, willow (Iñupiat, Arctic Alaska, 20th century). Simplot Collection. Gift of J.R. Simplot. | NA.506.54, split sedge root and split bracken fern or bulrush root (Pomo, California, undated). Dr. Robert L. Anderson Collection.](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=800,height=184,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PW216_basketmontage.png)

Examining Native American Basketry in the Studio Collections of Three Artists – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2014

Authenticity in Western American Paintings: Examining Native American Basketry in the Studio Collections of Three Artists

By Bryn Barabas Potter

Former Center of the West Research Fellow (2013)

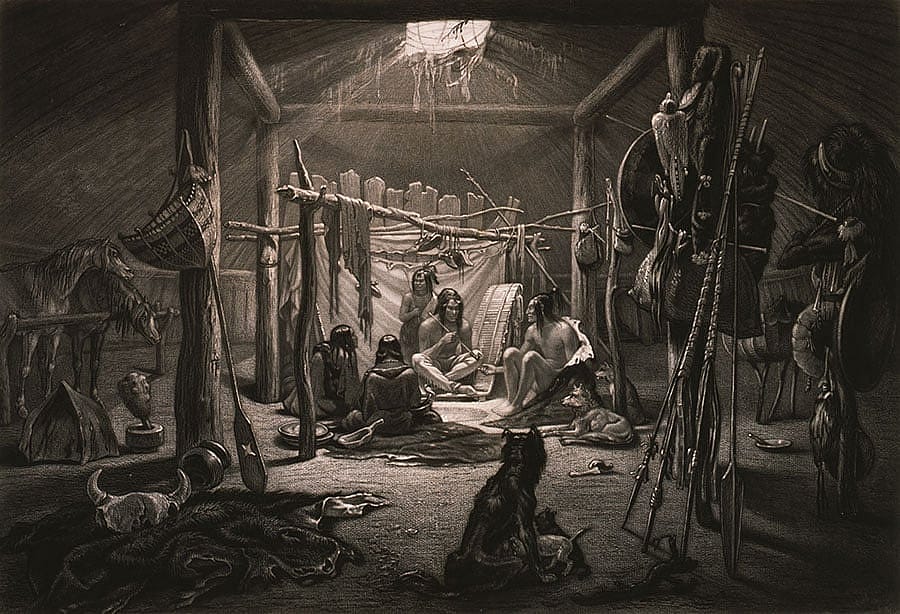

Examining the Karl Bodmer print here, you can see several baskets in the scene. But, did the artist capture the right baskets within the right context of people, place, and time? Specialist Bryn Potter asked herself that question as she studied the collections of three other artists at the Center of the West in 2013.

Arrows, baskets, moccasins—when you look at an American Indian object in a western painting, do you expect it to be accurate? Artists’ studios often included objects used as models in their artworks. Three noted artists—W.H.D. Koerner, Frederic Remington, and Joseph Henry Sharp—each owned American Indian items that are now in the collections of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. These tools of daily life, transformed into painters’ props, present a view of Indian life to the world. But, are they correct?

Basketry collections in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West

As a recipient of a Buffalo Bill Center of the West Research Fellowship, I began an exploration of the Center’s basketry collection in summer 2013 to determine if the baskets in the studio collections of artists Koerner, Remington, and Sharp could be identified in any of their works. Then, I analyzed whether their use of baskets was “authentic,” i.e. culturally correct within their context. It led to some interesting discoveries and ongoing research.

There are eighty-two baskets in the Koerner, Remington, and Sharp collections within the Whitney Western Art Museum. Over the course of a week, the Center’s Registrar Ann Marie Donoghue [now retired] and I examined and analyzed the baskets. One of our first decisions in this study was to dismiss Koerner from the group. The four baskets in his studio collection seemed more like average household items than “Indian props,” such as a splint basket used as a trash can. A limited survey of Koerner’s paintings did not reveal any images of basketry.

American Indian basketry—a functional art

Baskets form part of the larger web of Native artifacts that helped shape the global image of the American West. Most cultures made or used baskets. Basketry was used less in the Great Plains than in other parts of North America as parfleches (containers made from buffalo hide) or cooking vessels made from buffalo stomachs were easier to obtain. Gambling trays, usually coiled of willow stems, are an exception. The Cheyenne, Hidatsa, and Pawnee were a few of the tribes that made these objects.

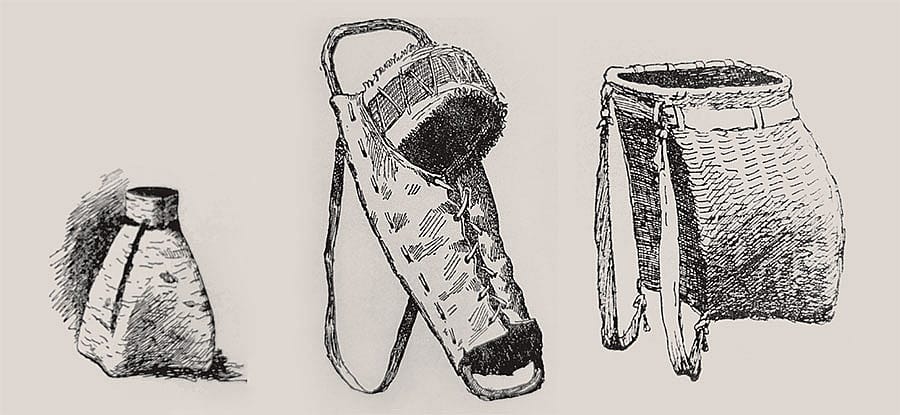

Basketry materials originated from local plant resources determined by the environment (Fig. 1). Birch bark or hickory splints harvested from a tree could be laced together into cylindrical containers or plaited in a basic over-under weave. Willow from the Plains and desert Southwest was a tough material that could be split and bent, suitable for both twining and coiling, the two main techniques of basketry. Amid the thick forests of northwestern California, thin maidenhair and woodwardia ferns lent themselves to tiny stitches and extremely fine weaving.

Baskets had a multitude of purposes, also influenced by the environment. For example, individuals created clam baskets for harvesting shellfish along the coast; they wore wide-brimmed cedar bark hats in the rainy Northwest Coast; and they carried large burden baskets to collect acorns or pine nuts for food. Indeed, the people’s primary use of baskets was in the gathering, preparing, and storing of food. Their basketry hats protected their heads, and their cradle-baskets carefully held their babies. Some baskets were used in ceremonies—from gifts to infants to mourning ceremonies, and from marriage dowries to the ornate regalia worn by dancers.

Most generally consider the period 1880–1930 as the height of Indian basketry. Collecting became a hobby for rich men and fashionable women. As anthropologists worked diligently to save baskets and record the passing of this utilitarian art form, prominent artists did their share of collecting too. Baskets joined the ranks of Indian items that littered their studios—ready at a moment’s notice to serve as models, adding touches of “authenticity” to a painting and setting the stage for a real or imagined view of Indian life in the American West. Let’s examine the studio collections of two of these artists

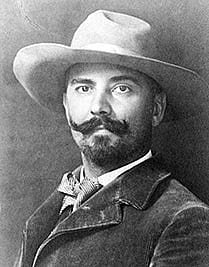

Frederic Remington (1861–1909)

Originally from upstate New York, Frederic Remington’s romance with the West began in 1881 when he first vacationed in Montana Territory. Trained as an artist at Yale College School of Art, he was attracted to the region and sketched cowboys, Indians, and western scenes for magazine and book illustrations, paintings, and bronze sculptures. Remington took many trips exploring the West—from Wyoming and Kansas through New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Mexico. His artifact-collecting activities took place during his early travel years. Peter Hassrick, Director Emeritus at the Center of the West and Remington scholar, told me that “after about 1900, he [Remington] stops so much collecting of objects and goes out West to collect color and light with his sketches.”

Remington was continually drawn to his beloved Adirondack Mountains and frequently visited Cranberry Lake, New York. A plethora of pen and ink sketches illustrate the 1891 edition of The Song of Hiawatha (Fig. 2), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem about an Indian hero set in the woodlands near Lake Superior. Remington’s sketches include a plaited wood splint pack basket and a mocock, or maple sugar basket, made of birch bark. Both baskets are of the type made by the Mic’maq, Passamaquoddy, and other northeastern tribes.

Remington draws from farther afield for his other illustrations, including a cradle basket next to Longfellow’s description of Hiawatha’s cradle in the book, “…He it was who carved the cradle of the little Hiawatha, carved its frame out of linden, bound it strong with reindeer sinews.”

Humorously, Remington’s illustration lacks both linden wood and reindeer sinew as it depicts an Apache cradle. The back is made of wooden slats on a curved wooden frame covered with rawhide, and a sunshade of willow woven in open twining. Not at all what Longfellow described!

These objects sketched by Remington for The Song of Hiawatha do not appear to be in the Center’s collection. Their appearance supports the idea that this artist was not a purist when it came to matching object with tribe. However, there is one extraordinary Apache olla basket from The Song of Hiawatha that is in the Whitney’s collection; I’ll discuss that later.

Illustrating tribally-affiliated baskets in Remington sketches

Tribal affiliation fares better with a trio of southwestern illustrations. Remington’s “Woman Grinding on the Metate,” an 1889 sketch for Harper’s Monthly, is a scene of a woman grinding food on a metate, or grinding stone (Fig. 3 & 4). The weaver would have coiled willow or cottonwood for the basket tray, with a black design in devil’s claw. Many southwestern tribes used the so-called “lightning” pattern. The basket in this sketch is similar to Remington’s Apache tray in the Whitney collection.

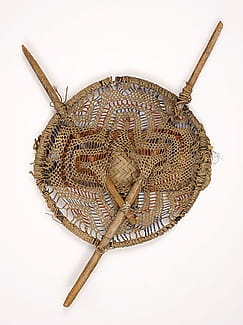

A kiaha is a knotted gathering net on a ring suspended from large crossed sticks, with a back pad plaited of yucca leaves. Remington drew a woman carrying a water jar on her back with one of these unusual devices used by several Arizona tribes. It is a detail in Sketches Among the Papago of San Xavier (Fig. 5 & 6), which appeared in the April 2, 1887, edition of Harper’s Weekly. There is a kiaha in Remington’s collection. Although records identify it as from the nearby Maricopa tribe, it is possible that it could have been the model for the drawing.

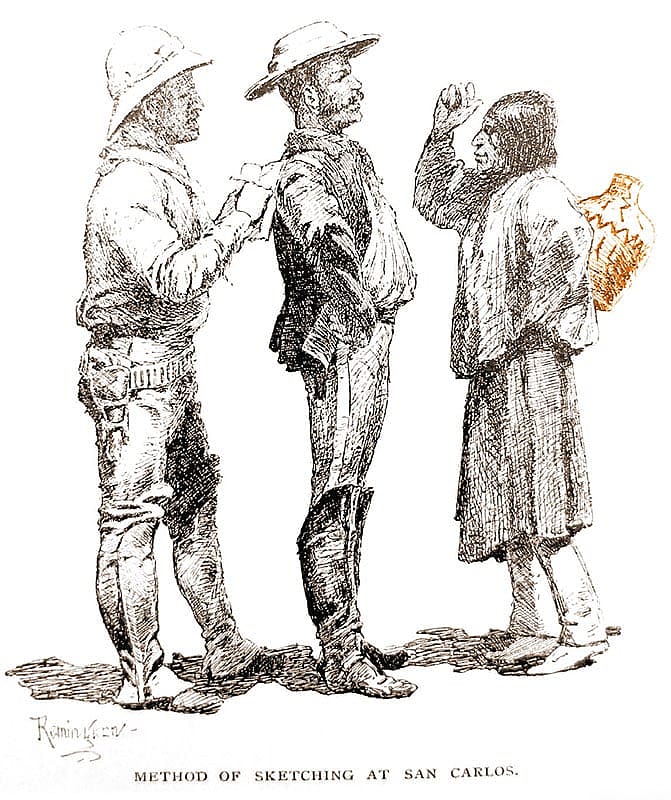

Remington’s self-portrait Method of Sketching at San Carlos appeared in Century Magazine in 1889. He shows himself cowering behind a soldier as he draws an angry Apache woman (Fig. 7 & 8). In this instance, the basket jar, or olla, carried on her back is a match between basketry type and tribal affiliation.

As a model for this drawing, Remington may have borrowed the shape and design from a basket in his collection mentioned above, and now housed in the Whitney. That same year, he used this basket for “Wicker Olla, Apache” in The Song of Hiawatha. Here, Remington demonstrated a lack of concern in his use of a southwestern basket to illustrate a northeastern story.

An extraordinary Apache olla basket

This outstanding basket, the Apache olla (Fig. 9), could be considered one of the Center’s masterpieces. The basket, 18 in. tall x 15 in. wide, is coiled of black devil’s claw with white lightning designs woven with either willow or cottonwood. The black seedpods of the devil’s claw plant (Proboscidea parviflora) used in this basket are 3–5 inches long. An inch of stitching to make coils of this size requires about a foot of raw material; consequently, this particular basket represents a huge amount of time to collect all of the necessary seedpods, and then strip them down to size for proper weaving material. Because of the investment of time for baskets of this sort, the so-called “negative-design” baskets are a rarity.

This basket is in pristine condition. It looks as if it were made yesterday, rather than more than a century ago. Interestingly, the handles on each side of the basket are of tooled leather and could very well be two sections of a belt. The curved design on the leather serves as a nice foil to the angular pattern on the basket’s body.

Joseph Henry Sharp (1859–1953)

Artist Joseph Henry Sharp was born in Ohio, attended art classes at Cincinnati’s McMicken University, and never outgrew his childhood fascination with American Indians. He first went West in 1883, traveling to New Mexican pueblos and the West Coast. Sharp spent time in Montana painting portraits of Plains Indians. In the early twentieth century, he collected Native items and lived and painted in his “Absarokee Hut,” a cabin on the Crow Indian Reservation. (This cabin is now part of the Center, located in one of the gardens.) In 1909, Sharp established a studio in Taos, New Mexico, and relocated there in 1912 where he played an active part in the Taos Society of Painters.

As with Remington’s collection, Sharp’s twenty-one baskets echo his travels. However, his collection seems a bit more eclectic. For instance, several Yu’pik baskets from western Alaska are exhibited in the Absarokee Hut, and one basket is possibly Egyptian. An African attribution is even possible, as upon surveying Sharp’s paintings, a Tunisian street scene came to light. (Sidi-bou-Said, [Tunisia], n.d., Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art). Most of Sharp’s baskets are from the Southwest, California, Alaska, and Africa.

Sharp’s depiction of baskets in his paintings are less definitive than Remington’s line drawings. Thus far, I’ve not been able to link any of Sharp’s own baskets to basket images in his works. He correctly portrays a group of Plains men in two works: using a gambling basket in The Stick Game (1906; Texas Christian University), and another basket to hold items in The Medicine Man (1948, The Gilcrease Museum). Pueblo basketry is properly portrayed in Sunset Dance—Ceremony to the Evening Sun (1924, Smithsonian American Art Museum), and Shelling Corn (n.d., Gerald Peters Gallery).

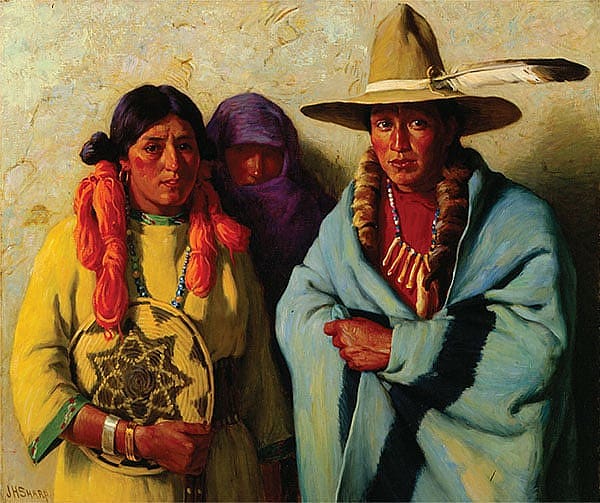

Sharp uses a very clear basket image in the Phoenix Art Museum’s Untitled (Three Indians), 1930 (Fig. 10). It is a coiled tray and would have been made of devil’s claw, willow, and perhaps cottonwood. One can find this type of basket among the Apache, Havasupai, and O’odham tribes. What it does not appear to be, however, is Pueblo. As a matter of fact, in surveying Sharp’s catalog of works, his Taos paintings often include Indians in Plains dress, with Navajo rugs and other non-Pueblo accoutrements, inside a Pueblo setting!

Conclusion

Based on the travels and subsequent object collecting by Remington and Sharp, one might conclude that they certainly understood the use of different materials and objects among the many Native American peoples they encountered. But when it came to their artworks, they seemed less inclined to maintain cultural authenticity and more likely to use items whose shape or design fit their needs. Simply put, they looked upon baskets through the eye of an artist.

Bryn Barabas Potter, M.A., BBP Museum Consulting, specializes in American Indian basketry. She is the former Curator of Basketry for the Southwest Museum of the American Indian—Autry National Center, and is currently Adjunct Curator of Anthropology at the Riverside Metropolitan Museum, Riverside, California.

Potter writes, “I conducted a non-exhaustive search of collections online for works of Koerner, Remington, and Sharp that included representations of baskets. I also reviewed the archives and photographs from the McCracken Research Library for this project. The parameters of the Fellowship did not allow for a more extensive search, although I plan to continue looking for baskets in the works of Remington and Sharp as opportunity allows. Many thanks to [now-retired] Registrar Ann Marie Donoghue for her assistance.”

Post 216

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.