Pearl Harbor Attacked! United States Declares War on Japan!

December 7, 1941, in the early morning hours aboard Ford Island, Hawaii, sailors and Marines stood at morning muster when the buzz of airplanes cut the air. In a blink, confusion turned to horror as the planes were identified as Japanese Zeros and bombs rained from the sky eliminating the few PBY (maritime patrol) planes positioned there as well as much of the airfield.

While the December 7th attack was a surprise for those on Pearl Harbor, the drums of war had been beating closer to America for years. The ink had barely dried on the Versailles Treaty ending the World War I when troubles began festering in Europe and Asia primed to explode into what would be World War II.

Crawling out of the Great Depression, most Americans weren’t focused on international conflicts and reports of atrocities in Europe fell on deaf or unbelieving ears. By 1941, however, the war in the Pacific and Europe had pounded too loud to ignore.

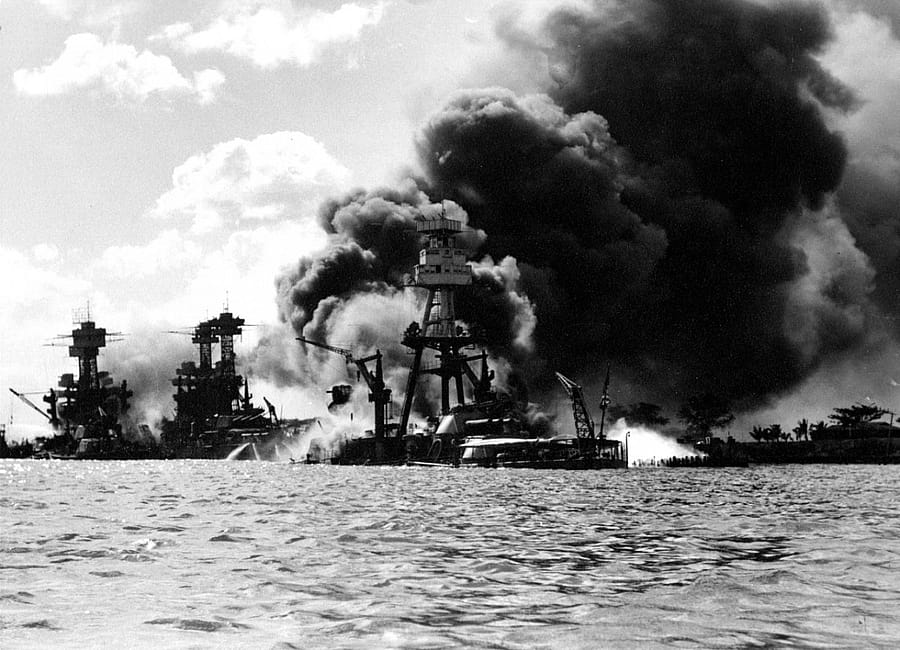

It was not the calls for intervention from British allies however that pulled the United States into the fight: it was Japan’s declaration of war against China in 1937. This action was met with a hail of economic sanctions by the United States against Japan, and by 1941 negotiations between the two countries had all but disintegrated. The U.S. government knew war was inevitable, but never imagined Japanese forces would attack United States’ soil. Most believed the attack would occur into the Indies, Malaya, and probably the Philippines. But in December of 1941, the Japanese Navy sent a force greater than any that had been seen on the world’s oceans, and at 8AM on December 7th Pearl Harbor would be set on fire.

Ford Island, home to Battleship Row, was the epicenter of the attack, and continued to reel with the next wave of bombs aimed at the line of ships: Oklahoma, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, Arizona, Nevada. These were the battleships that suffered the most impact from the torpedoes, high-level bombing, and dive-bombing attacks. Over the course of the attack 40 torpedoes were dropped by Japanese aircraft, approximately 14 of these hit the Oklahoma and West Virginia.

Also, severely damaged on the eastern shore were the USS Pennsylvania, the flagship of the battle fleet, destroyers: USS Cassin, USS Shaw, and USS Downes. The light cruiser, USS Helena, and minelayer USS Oglala were both sunk by Japanese torpedoes.

The soldiers, sailors, and Marines on Pearl Harbor and aboard the ships moored there, while stunned for a moment, soon reacted with what countermeasures they could. Mobilized, these men manned antiaircraft guns, or even their rifles; others took to the skies in what aircraft could be found including a few Army P-40 and P-36 pursuit ships.

Ensign Theodore Wood Marshall, an assistant flight officer, was one of those who took action. When the attack began, he was located in the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters on the opposite side of Ford Island. Commandeering a truck during the height of the attacks, he made numerous trips between the officer’s quarters, enlisted men’s barracks, and squadron area. While shuttling men to their battle stations, his truck was riddled with bomb fragments and bullet holes from not only Japanese fire, but friendly fire in the confusion of the attack.

Ensign Marshall then noticed an unmanned Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighter. He’d never flown that type of plane, but this didn’t stop him. Unfortunately, when he started to taxi this drew the attention of Japanese bombers and in the second wave of bombs the Wildcat was left unfit to fly. But Marshall was unharmed and still determined. He rushed over to a Douglas TBD-1 Devastator, another plane with which Marshall was unfamiliar. This time, he managed to get the Devastator off the ground and chased the retiring Japanese for 150 miles. The Devastator being a slower plane meant Marshall could not catch the enemy and had to return to Oahu. For his actions Marshall received the Silver Star. Marshall continued to serve valiantly in the Navy until he retired in 1959.

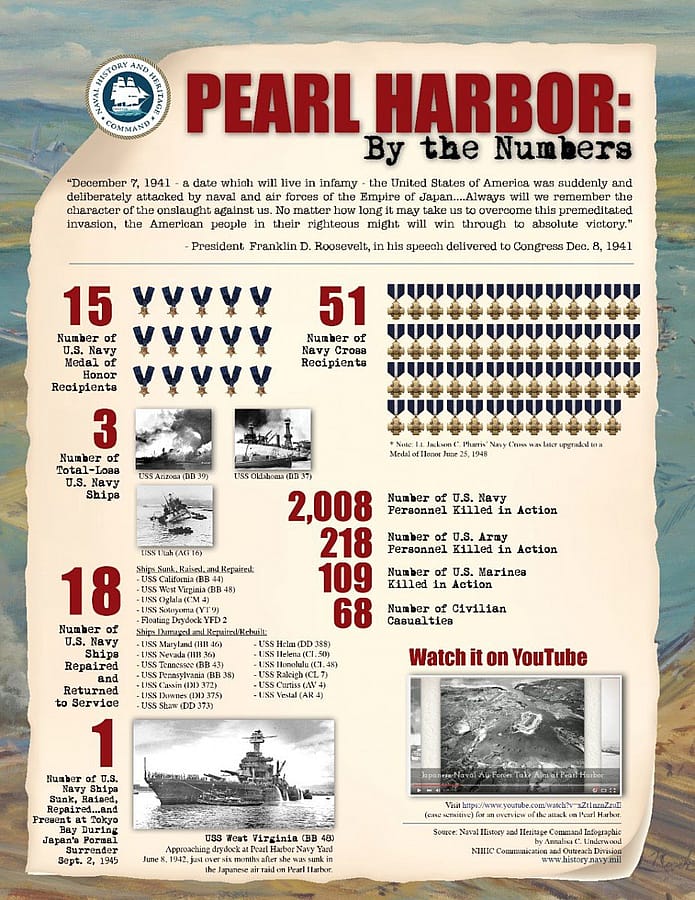

There were many heroes aboard Pearl Harbor that day. Among those heroes, there were 15 Medal of Honor recipients and 51 Navy Cross recipients.

The onslaught lasted two hours. The devastation was great. Oil-soaked survivors walked around in shock until escorted to the tower or Hangar 37 on Ford Island. Hospital ships and the main hospital on Pearl Harbor were overrun with casualties.

The USS Arizona sank with over 1000 men trapped on board. The ocean would remain their final resting place. The USS Oklahoma capsized with men trapped and tapping on pipes, praying for hours, until some could be rescued, while others were forever lost. In fact, all battleships at Pearl Harbor suffered extensive damage. The three total losses were the Arizona, Oklahoma, and Utah. Over 2,400 lives, military and civilian, were lost and over 1,000 more were wounded. Twenty-one ships of the Pacific Fleet were sunk or damaged, though six of the battleships damaged were salvaged and repaired and fought in later battles.

For all the devastation, the attack did not accomplish the objective of destroying the Pacific Fleet as Japan intended. The main targets, the three aircraft carriers; USS Enterprise, USS Lexington, and USS Saratoga were not at Pearl Harbor on December 7th. Also, Japanese bombs did not destroy the oil storage tanks, shipyard and repair shops making it possible for the United States to recover in a quick turn-around. More importantly, the attack did not destroy the spirit or will of the American people and the “day of infamy” galvanized a nation.

With the giant awake, a divided America united in a haze of revenge and instead of keeping the United States out of the war in the Pacific, the U.S. fully committed to a war against Japan in the Pacific. For Great Britain, who by this time was fighting alone in Europe, the Lend-Lease Act, which provided supplies in support of the war effort there was nullified, and the United States joined the fight in Europe, as well.

This war, unlike World War I, would not be a one-year commitment for the forces fighting or those on the Homefront, but would become the largest armed conflict in human history ranging over six continents, all oceans, and costing 50 million lives both military and civilian.

WWII continued with blog, Winchester Goes to War- The M1 Carbine

Sources:

Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C. www.history.navy.mil

Cressman, Robert J. “Pearl Harbor Toughness Takes Flight: Ensign Theodore W. Marshall” The Sextant. http://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2016/12/05/pearl-harbor-toughness-takes-flight-ens-theodore-w-marshall/?fbclid=IwAR1cgmpfNYCa-TuVHGNcLIlK7q8zE2YYggXTFT5LFg-j5Oaj1DBUd-uxOmo

Written By

Kirsten Arnold

After years in Washington, D.C., Kirsten Arnold escaped D.C. traffic and moved back home to Wyoming where she can enjoy the mountains and open spaces. She holds a Master of Arts in Military Studies, Naval Warfare. In 2018, Kirsten assisted the McCracken Library with the Winchester Manuscript Collections.