Finding the Real Frederic Remington – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2013

Finding the Real Frederic Remington

By Peter H. Hassrick

Back in the mid-1980s, the then-named Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, embarked on an ambitious exhibition plan to reveal the hidden talents of American artist Frederic Remington. In his lifetime, Remington was revered mostly as the “pictorial historian of the Great West,” (“Painting the West Many Colors,” New York Sun, December 30, 1892), and well through the next two generations, that label stuck. He was appreciated almost exclusively for the accuracy he supposedly brought to the depiction of the frontier saga.

His actual accomplishments as a painter and sculptor, his aesthetic vision, the evolution of his technique and style, and his contributions to the corpus of American art were all subverted by the public’s expectations of him as a historical literalist. The Cody exhibition was designed as something of a corrective to those entrenched perceptions. It ended up doing even more; it was the impetus for a catalogue raisonné (French, literally, “reasoned catalogue”; i.e. a systematic annotated catalogue) on an artist who is one of the most imitated and faked in all of American art.

The Center teamed up with the Saint Louis Art Museum, and the resulting exhibition, Frederic Remington: The Masterworks, traveled also to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Among the several chapters in the accompanying catalogue was one by Saint Louis curator Michael Shapiro (now Director of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia) on Remington’s genius as a sculptor. As director of the Center at the time, I also contributed an essay on Remington’s developing talents as a painter.

As I was building the exhibition checklist for the paintings, it occurred to me that it might be a worthy effort to assemble concurrently an illustrated accounting of all Remington’s flatwork—oils, watercolors, and drawings. The Center’s McCracken Research Library had recently acquired an invaluable multi-volume set of scrapbooks, assembled by bibliophile and Remington expert Helen Card and filled with clippings of nearly every known Remington illustration. From that source, it looked as if there might be approximately three thousand such works.

Collating these pieces—and tracking down as many of the originals as possible—would, it seemed, make a valuable contribution to Remington scholarship. It might also aid in better understanding the stylistic and technical progression that was central to the exhibition’s mission. To accomplish this task, I enlisted the assistance of Melissa J. Webster, who soon became a vital part of the vetting process for decisions about the veracity of original works that came to our attention. We considered whether they should be added to what by 1984 was being referred to not simply as a listing, but a veritable Remington catalogue raisonné.

A catalogue raisonné is born

I had started my museum career in 1969 as Curator of Collections for the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Its sizable and vastly important collection of Remington art, combined with the impressive complementary holdings of the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, also in Fort Worth, became the subject of my first book, Frederic Remington: Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture in the Amon Carter Museum and Sid W. Richardson Foundation Collection published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in 1973.

As a result of that publication, and an associated retrospective exhibition that I organized at the museum the same year, I emerged as something of an over-night “expert” on Remington’s art. People began to contact the museum, asking for my opinion on everything from paintings and sculpture to memorabilia and biographical facts. I accepted the role rather reluctantly and quite sporadically, continuing in that vein after I left the Carter Museum in 1976 and became the director of the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] in Cody.

In 1984, with the nascent stirrings of a catalogue raisonné surfacing, I decided to formalize the authentication process. To that end, and after much wrangling with the Center’s legal counsel, the Center’s Board of Trustees approved a uniform “Request for Authentication Form” and “Procedural Guidelines” for the process. Within these contractual documents and logistical imperatives, the following provisions had to be met: 1) The request had to come directly from the current owner of the work (not a dealer or other representative) who was required to sign a declaration of ownership and a waiver of liability; 2) the owner needed to be an active member of the Center’s Patrons Association; and 3) the object had to be personally inspected by me (insured and shipped to and from the museum at the owner’s expense).

Between 1985, when the program was formally initiated, and 1996, when the two-volume Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings was published, 248 works were reviewed. Only fifty-three of those, or slightly less than 20 percent, were deemed to be original works by Remington; these were then added to the catalogue raisonné. The authentication process, now titled Remington “examinations,” has continued with only modest interruptions since then. Once the raisonné was published, the percentage of authentic and inauthentic pieces has remained constant.

In 1996, the Center organized, hosted, and circulated a didactic exhibition about the process of compiling a catalogue raisonné. Titled In Search of Frederic Remington, the show traveled to four museums after its debut in Cody. Central to this exhibition’s purpose were questions of how an authentic work is determined and what sort of inauthentic works existed. Rather than referring to all inauthentic objects as “fakes,” they were categorized according to a carefully considered variety of types. Webster, who contributed two of the four introductory chapters to the catalogue raisonné (which served as the catalogue for the exhibition), wrote on Remington connoisseurship in a chapter called “The Frederic Remington Catalogue Raisonné.”

Webster articulated four types of inauthentic works, categorizing them either as pastiches, copies, fakes, or forgeries. The vetting Remington committee continues to use these terms today. None of these terms, except for forgeries, necessarily implies intent to deceive, that is, until or unless the object’s creator or some subsequent party applied a “Remington” signature. Copies, for instance, may be unsigned, having been painted as an artistic exercise or simply for the pleasure of a Remington-like image on the wall. But when a signature is added, a forgery is created.

Copies

Of all the categories of non-authentic works, copies seem to be the most prevalent. It is probably these pieces that occasioned the Remington scholar R.W.G. Vail of the New York Public Library to exclaim as early as 1929 in the library’s Bulletin, that because of Remington’s popularity, there were probably more inauthentic Remington canvases on the market than by “any other American painter.” Since Remington was an illustrator for most of his career—and even in his later life, when he sought recognition as a painter, most of his paintings were illustrated in popular magazines—his images were ubiquitous and readily available to copy. Approximately 40 percent of all the inauthentic works submitted to the Center’s program since 1985 fall in the category of signed, fraudulent copies.

A prime example of a fraudulent copy is owned by the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York. This color oil derives from a 1910 Collier’s color illustration of a painting titled Pool in the Desert [click here to view], currently in private hands. The Collier’s illustration was cropped for some reason by the magazine’s editor so that the pool is not visible. The signed, fraudulent copy, with the Collier’s reproduction as its model, was manufactured by a painter who was unaware that Remington’s original composition was both more expansive in scale and thematically true to the title.

Copies come in many styles and methods. One of the most prolific copyists—whose name is still unknown—had a propensity for employing underlying pencil gridlines, a technique of “squaring” images for transfer. This technique has been noticed by the vetting committee, which comprises three members in addition to me: Laura Foster, curator of the Remington Art Museum; Dr. Emily Neff, curator of American art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Dr. Sarah Boehme, director of the Stark Museum in Orange, Texas. These experts, representing some of the most distinguished collections of Remington’s art, have looked at a dozen or more copies like this, and, with tongue in cheek, have dubbed their author “master of the grid.”

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston owns one example, a black and white oil on canvas copied from another Collier’s illustration, The Grass Fire [click here to view]. The original [click here to view] is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum. Another copy, Indians on Horseback, relates similarly to an original work in the Remington Art Museum titled The Snow Trail. The originator of both these copies evidenced a crudity of paint handling, brushwork, and figural treatment—definitely not the work of Remington.

The style of another copyist, a man who generally worked in watercolor, has been ascribed to Harry Sickles, who is thought to have practiced his craft in Chicago and Minneapolis. Sickles was famous for translating known Remington images into rudimentary, miniature watercolor vignettes that decorated the pages of books, many in first edition volumes that Remington had written. He also produced independent artworks and is thought to have been the creator of what has come to be known as the fake “kicking horse signature.” These phony signatures appear with many of these images and as ersatz inscriptions on title pages of some Remington books.

Fakes

Fakes constitute the second largest category, approximately 23 percent of inauthentic works submitted to the Remington certification program. For our purposes, a fake is described as a painting or drawing that does not relate to any known original work by Remington, but is given a fraudulent signature and is generally of a subject in which the artist might conceivably have had an interest. Fakes are more difficult to discern and require more connoisseurship than copies since a copy can be placed next to the original (or an illustration of the original) to compare technique. Fakes, as defined above, have no point of comparison, so years of experienced work with Remington’s body of work must be brought to bear to render a valid opinion.

A representative example of a fake, brought forward in 1995, is an untitled oil on canvas depicting two Indians on horseback working to rope a third horse. Remington was known to have painted several compositions of this sort, including a Harper’s Weekly ink wash illustration, Two Ghosts I Saw from 1891, and an oil titled The Ceremony of the Fastest Horse of 1900, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The untitled fake borrowed galloping horses in profile across the picture plane, but the underlying drawing, the anatomical rendering, and the paint handling in the fake are noticeably unsophisticated and not reminiscent of Remington’s hand. The fake is signed “Remington,” but the letters are labored rather than fluid, as we would expect with any authentic signature. In addition, the artist’s materials are not those typically used by Remington. He uniformly employed F.W. Devoe & Co. canvases and metal, 1888 patented stretcher devises. The fake painting was on an unmarked canvas and used simple wooden stretcher keys.

Forgeries

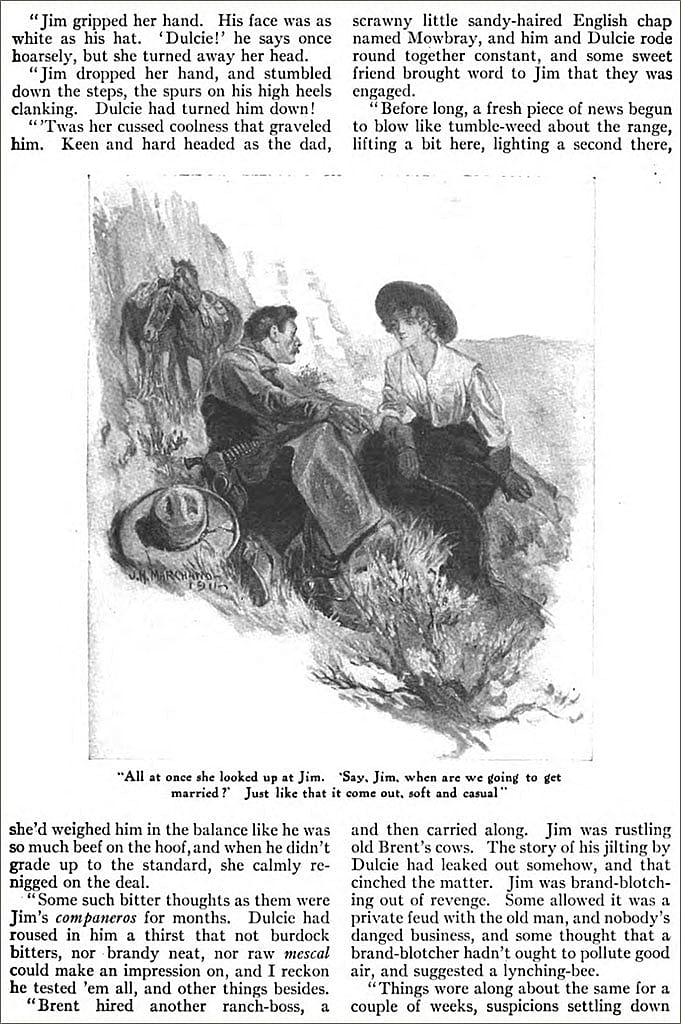

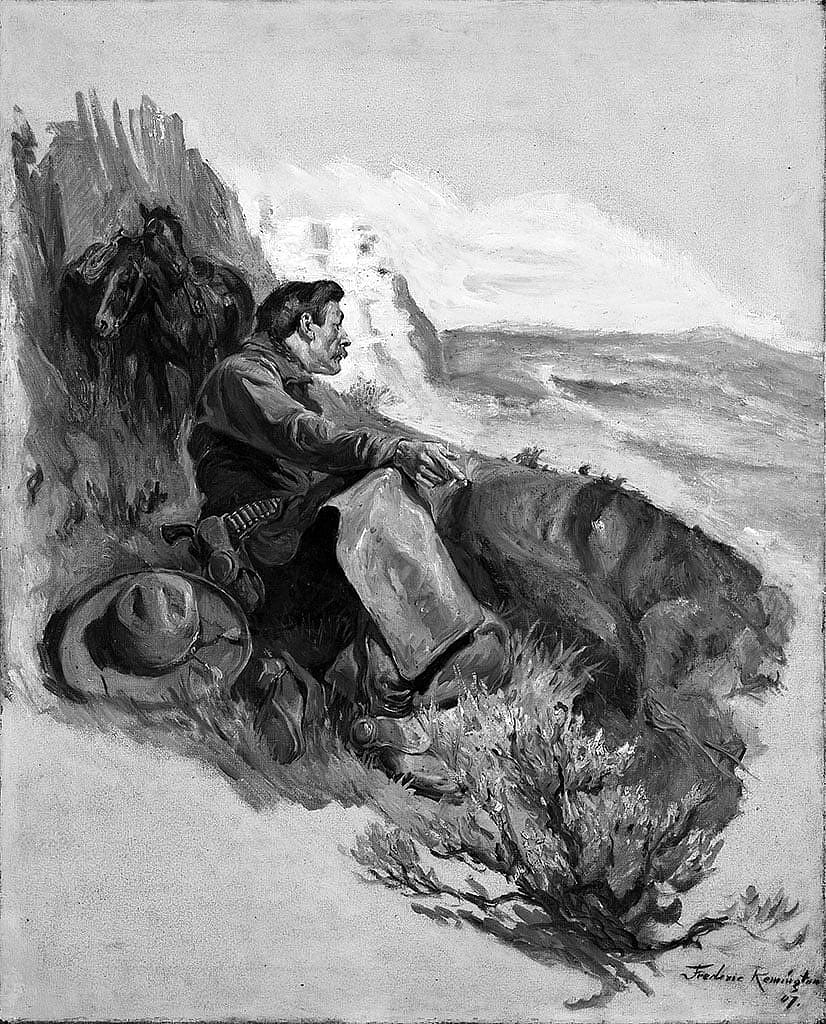

About 16 percent of all non-original items presented to the vetting program have been forgeries. These are typically paintings and drawings by a recognized artist whose signature has either been painted out or cut off, and replaced by “Frederic Remington.” Sometimes the authorship of the painting is readily recognized, as in the case of the famous set of black and white oils collected by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks for their Los Angeles home and known widely as the “Pickfair Remingtons.” As it turned out, these works were created by the hand of a somewhat less-renowned New York illustrator, John Marchand, and had appeared as plates for stories published in popular American magazines during the teens and 1920s.

An example of a forgery is an untitled work that was submitted in 2004. It had illustrated Elizabeth Frazer’s story, “The Brand-Blotter,” under the title of “All at Once She Looked Up at Jim” in Cosmopolitan Magazine, in 1911. The forger not only signed the work as Remington’s and re-dated it to 1907, but altered the composition to illuminate the story’s heroine, since Remington was known to have rarely painted women. Other noted American artists whose works have been re-ascribed to Remington over the years include Harvey Dunn, Herbert Dunton, and Gilbert Gaul. It was assumed that these alterations were carried out because Remington’s market was stronger than some of his colleagues.

Pastiches

Pastiches are works that copy elements of two or more known Remington paintings or drawings, and are signed with the intent to deceive. This category of inauthentic pieces is the smallest. Only twelve pastiches have been submitted, or slightly more than 2 percent of all works brought before the Remington vetting committee.

In summary…

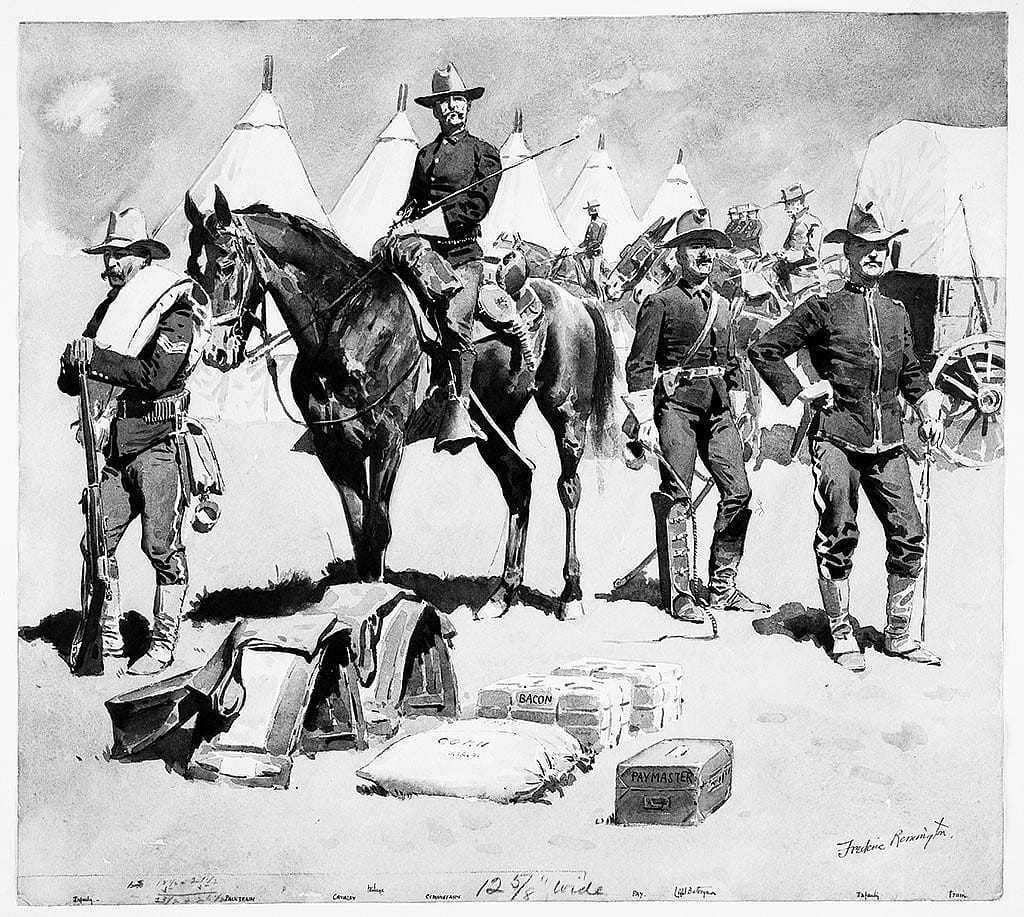

These four categories, then, are representative of several types of inauthentic flatworks that have been submitted since the Remington examination program was formalized in 1985. All tallied, 497 two-dimensional works have come forward and official opinions rendered. Of those 497 pieces, 109 (22 percent) have been determined to be original, such as the untitled 1894 ink wash drawing (opposite) of infantry and cavalry assembled in camp during the Spanish-American War that came before the committee in 2004; it was not known to exist before that date. Another 384 pieces (77 percent) were determined not to be original, and four works (1 percent) were issued an inconclusive opinion.

The Center maintains records of all opinions, and by contract with the owners can publish or use for research any results of the committee’s findings. The group assembles in Cody annually to do its review of works recently submitted. Generally. about twenty to twenty-five pieces are inspected at each meeting. Newly-discovered original works are incorporated into the files for the Remington catalogue raisonné, which will be republished in electronic form to complement the 1996 two-volume printed set.

I am most grateful to the Center and its director [at the time this article was written] Bruce Eldredge, for their support in the development of this article. Special thanks also go to Laura Fry, now of Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for researching and collating the statistics for this piece, and for tracking down many of the images used here, and to Laura Foster of the Remington Art Museum for her assistance with the preparation of this article.

About author Peter Hassrick

Peter H. Hassrick was a writer and independent American art scholar who focuses on the West. Before his death in 2018, he served as Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He was also the Director Emeritus of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum, Founding Director Emeritus of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma, and founding Director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Before that, Hassrick served for twenty years as the Director of the Center. He held the post of Curator of Collections at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth for five years.

Hassrick was born in Philadelphia and raised in Denver. He earned a BA in History, University of Colorado and a MA in Art History, University of Denver. Selected books include Frederic Remington (Abrams, 1973), The Way West (Abrams, 1977), The Rocky Mountains: A Vision for Artists in the 19th Century (U of Oklahoma Press, 1983) with Patricia Trenton, Treasures of the Old West (Abrams, 1984), Charles Russell (Abrams/Smithsonian, 1989), Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné (BBHC, 1996) with Melissa Webster, Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor (Amon Carter Museum, 2003), In Contemporary Rhythm: The Art of Ernest L. Blumenschein (U of Oklahoma Press, 2008) with Elizabeth Cunningham, The American West in Bronze (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013) with others, Painted Journeys: The Art of John Mix Stanley (U of Oklahoma Press, 2015) with Mindy Besaw, Drawn to Yellowstone: Artists in America’s First National Park (WordsWorth / Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 2016), and The Best of Proctor’s West: An In-depth Study of Eleven of Proctor’s Bronzes (Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 2017) with others. At the time this article was written, he had recently completed an updated edition and digital component of Frederic Remington Catalogue Raisonné.

Post 222

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.