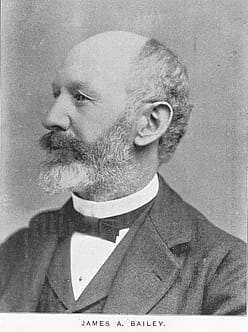

This is Not a Circus!: James A. Bailey Redefines Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show

The “Little Napoleon of Show Business”

When you think of the Wild West, it is not likely that James A. Bailey is a name that comes to your mind. As one of the main partners of Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth, it seems he has largely been left out of the limelight. While the lesser known name, Bailey’s is arguably the greater one in show business! Bailey’s understanding of the entertainment industry of his day built and sustained the platform from which the greatest showmen, perhaps of all time, could shine.

Born July 4, 1847, in Detroit Michigan, James Anthony McGinness was destined for an unusual life of adventure. At the age of 10, McGinness left home. For a while, he worked on a rural farm making $3.50 per month then for a hotel in Pontiac, Michigan as a bell-boy. Fred Bailey, the general agent of Lake & Robinson Circus, engaged young McGinness to assist him. It’s from this mentor that McGinness took his name, becoming James A. Bailey. Fred Bailey was supposedly the descendant of famed circus-pioneer Hachaliah Bailey who bought the first elephant in America. Taking his name lent great credibility to James’ own position in the industry.

James A. Bailey had such a reputation in the circus world that he was dubbed, “The Little Napoleon of Show Business”! “When Bailey picked up a newspaper he did not first turn to the baseball score, nor did he stop to read the news of the day until he had first scanned the market reports and ascertained the price of cattle, hogs, flour, potatoes, cotton, tobacco, butter, eggs, etc. that was his barometer to business conditions,” (Griffin, 15).

Rising from billposter to general agent to owner and partner by 1872, Bailey was only 30 years-old. “Cooper and Bailey Great International Shows” was very successful, touring internationally in Australia, New Zealand, South America, and India before returning to the United States in 1878 and consolidating with “Howe’s Great London Shows”. In 1880, a baby elephant was born to the Cooper, Bailey, and Co.’s circus. P.T. Barnum sent a telegram to Bailey offering $100,000 for the baby elephant. Instead, Bailey used the telegram to widely publicize his own circus. It was at this time that Barnum decided to join forces with Bailey officially forming “Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth”. It should be noted that while Barnum was the Showman, Bailey was the businessman who made the show possible. Barnum became well known for “The Greatest Show on Earth” near the end of his life, while Bailey had grown up in show business. It was under Bailey’s management that The Greatest Show on Earth acquired the Forpaugh and Sells Bros. Circus in 1890. P.T. Barnum passed away April 7, 1891, leaving Bailey the sole proprietor of the Barnum and Bailey Greatest Show on Earth along with all its assets. The pattern of the businessman behind the showman would continue in a surprising way in 1895!

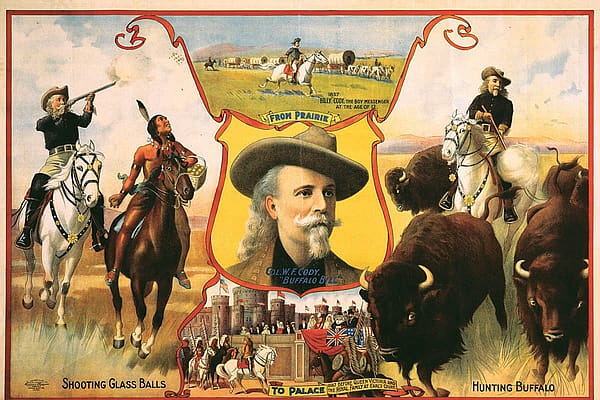

Buffalo Bill Partners with James A. Bailey

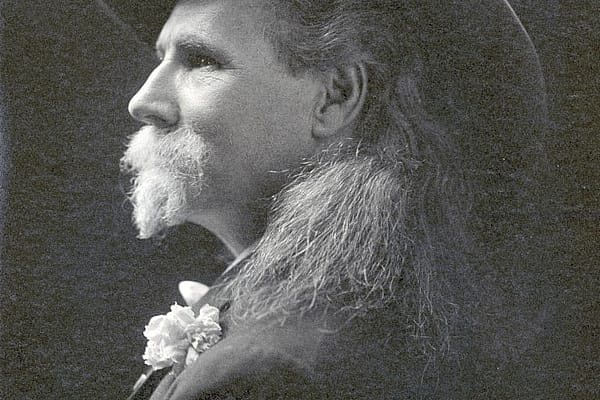

In 1895, there were very few competitors to Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth. Bailey’s greatest competitor was the Five Ringling Brother’s Circus followed by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Unfortunately for Buffalo Bill, his Wild West show was once again facing financial peril. Following the Chicago World Exhibition season in 1893, Buffalo Bill went into debt keeping the show open for the 1894 season at Ambrose Park in New York City. “With expenses averaging $4,000 a day, attendance was not large enough. By mid-July, only a year after his most profitable season, Cody was complaining that he was in the tightest squeeze of his life. In January 1895, he asked Nate Salsbury, his business partner and show manager, to go on his note for $5,000,” (Russell, 378).

Salsbury became ill at the end of the 1894 season. “To fill the gap caused by his (Nate Salsbury) absence from active management, Salsbury and Cody signed an agreement with James Bailey of the Barnum and Bailey Circus. Bailey was to provide transportation and touring expenses in return for a share in the profits” (Blackstone, 27). Effectively, this made James A. Bailey the active manager of the show and he was billed as such in the 1895 season program. This arrangement between The Greatest Show on Earth and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show may seem arbitrary at first but it was excellent business sense!

Redefining Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show

In the early years of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, “tours were made in a train of 18 cars and aboard a Mississippi steamboat that was abandoned at Rodney’s Landing. The show was still fairly small (about 300 people), and performances were given in baseball fields, race tracks, and driving parks that already had some seating… Touring proved expensive and exhausting for a group this much larger than a melodrama troupe, and Nate Salsbury instituted the idea of the long run in 1886. He would rent a large piece of ground near a big city, usually, New York and the Wild West would set up a semi-permanent camp there, staying four to six months” (Blackstone, 37).

This was fairly successful through the summer of 1893 at the World Exhibition in Chicago. Unfortunately, the following season at Ambrose Park in New York was financially devastating for Buffalo Bill. Bailey revolutionized the show’s performance style and schedule. Instead of staying in a major city for the season, the Wild West show would now travel by train throughout the small towns of the United States stopping for one-day “stands”.

Traveling by rail in 1895, they performed in 131 stands, in 190 days, and traversed over 9,000 miles. The show used 52 rail cars which was more than both The Greatest Show on Earth and the Ringling Bros. Circus. Meanwhile, Nate Salsbury gathered a break-away Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show that was marketed specifically to the Deep South and the African American community there. This show ultimately failed. However, the 1895 season, though considered as brainstorming tours, proved to be highly profitable.

The following year, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show played at 132 stands over the course of 104 cities and a route of 10,000 miles. Bailey also was responsible for including advertisements in the programs adding an extra layer of profit to the show.

This was an interesting time in the life of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show! In 1896, military parades and drills of every kind became a very popular addition to their acts. 1898, the show added a “Bevy of Rancheras” otherwise known as cowgirls who turned out to be extremely popular. Buffalo Bill’s influence and national acclaim added to James A. Bailey’s business acumen made the Wild West a household topic across the nation. From 1900-1902, the show became a loud advocate on the side of various important historical events including the Spanish American War and the Boxer Rebellion in China. Many thought Buffalo Bill himself would take his rough riders to fight in the Spanish American War but the conflict ended before he had the opportunity to leave the States.

Some scholars argue that Bailey’s influence cheapened the quality of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West by adding more circus-like events, sideshows, and the intense travel schedule that took a major toll on the entire crew including Buffalo Bill. It is likely that even if Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had not continued past the 1894 season, he would have been remembered for his role in shaping the legend of the American West.

Bailey receded from his very public association with the show after 1895 although he continued to manage Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show until his death in 1906. It was on his direction and financial support that the Wild West show toured Europe from 1902-1906.

“It has been said that Bailey kept the Wild West in Europe for four successive seasons to keep it out of competition with his circuses in the United States. While that may have been a factor in his management, it is not the full story. The success of the Wild West was also in his personal interest, and he may have felt that it was then a better show for Europe than for the United States… He also traded territory with his Barnum and Bailey Circus, which had made a successful tour of Europe from 1897 to 1902” (Russell, 439).

Meanwhile, to keep paying for his various business investments or experiments across the west, Buffalo Bill constantly had to borrow money from his partners for the show to go on. It turns out, “He had sold two-thirds of his show to Bailey and taken out an additional note with him for $12,000, but he had no receipt to prove his claim that the $12,000 had been repaid” (Blackstone, 29).

The Bailey Estate Trust

After Bailey’s death April 11, 1906, his wife Ruth L. Bailey inherited his entire estate. She did not want to remain in the show business and began seeking ways to sell each of her husband’s interests in the industry. Ringling Bros. began negotiations immediately to purchase from her The Greatest Show on Earth. Bailey’s death then began to cause financial concerns for Buffalo Bill when it was discovered that he still supposedly owed Bailey $12,000. Cutting most of the circus, military, and political acts Buffalo Bill brought the Wild West show back to its roots and did so successfully despite his financial difficulties. “With this show, Buffalo Bill opened the 1907 season in Madison Square Garden and toured for two years of numerous one-day stands – the only two years of his life he operated without a partner. He owned only one-third of the show, and that third was heavily mortgaged” (Russell, 445).

The Bailey Estate Trust sought out Gordon W. Lillie (Pawnee Bill) to partner with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

“I was appearing in Wonderland Park Revere Beach, Mass. in 1907, when I received a message from W.W. Stewart, administrator of the Bailey estate, asking me to come to New York at once, as he had a great show proposition to make me that would make me rich. It was the combination of the Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill shows” (Wilson & Martin, 190).

“In June 1908, Lillie broached the subject of the merger to Cody at Keene, New Hampshire, but gave up after Cody flatly refused to consider changing the name of the show to include Pawnee Bill” (Russell, 447). Still, Lillie gave Buffalo Bill some first-rate advice on which route he should take that season which proved both accurate and profitable. “A further incentive was that Cody had been having trouble with Cooke, general manager representing the Bailey estate, and in a fit of temper, had knocked Cooke down. The Bailey heirs threatened to close the show unless Cody apologized. He did,…” (Russell, 447).

“Orders came from headquarters in 28th St. New York City ‘Unless Cody apologizes and begs your pardon close the show at once and ship it back to winter quarters, Bridgeport, Conn.’ The Col. held out till the last moment refusing to so humble himself but when he saw them making actual preparations to close the show, he asceeded [sic] and apologized most humbly” (Wilson & Martin, 192).

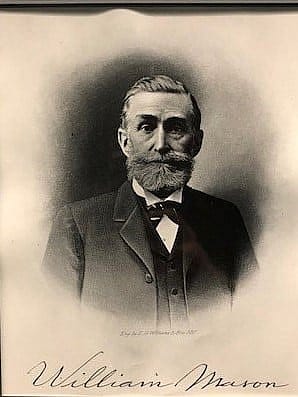

Pawnee Bill subsequently bought the two-thirds of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show from the Bailey Estate Trust and the equipment needed from the Ringling Bros. Circus. The merged shows became known as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West combined with Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East” or the “Two Bills Show”. Realizing that the greatest asset the Wild West show was Buffalo Bill himself, Pawnee Bill treated him as an equal partner and offered him the opportunity to earn back a half interest in the show, which Buffalo Bill finally achieved in 1911.

There is “no business like show business”, but it is a business. Behind the performances and the great stars are the visionaries who manage the promotion of the show and the logistics of making it a reality. Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum Dr. Jeremy Johnston weighs in, “Here you have what one could consider a cut-throat businessman in Bailey and a popular star like Buffalo Bill conflicting with one another. There has always been this tension, even today in Hollywood, does an Oscar make a movie, or is success due to box-office returns?” The dreamers, like P.T. Barnum and Buffalo Bill, are the ones we remember but the realizers of those dreams like Salsbury, James A. Bailey, and Pawnee Bill should not be forgotten.

Bibliography

Blackstone, S. J. (1986). Buckskins, bullets, and business: A history of Buffalo Bills Wild West. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Griffin, C. E., Dixon, C., & King, A. D. (2010). Papers of William F. Buffalo Bill Cody: Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Russell, D. (1982). The lives and legends of Buffalo Bill. Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press.

Wilson, R. L., & Martin, G. (1998). Buffalo Bills Wild West: An American legend: Featuring the Michael del Castello Collection of the American West; with portfolios of treasures from the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming and the Autry Museum of Western Heritage, Los Angeles, California. New York, NY: Random House.

Written By

Liz Bowers

Liz Bowers is a Wyoming college student working with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in summer 2018 to gain experience in Public Relations. This includes activities with social media, review sites, events, writing, and photography. In her spare time, Liz enjoys hiking, trail riding, and stories of all shapes and sizes.