We Are a Dancing People – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2017

We Are a Dancing People

By Majel Boxer

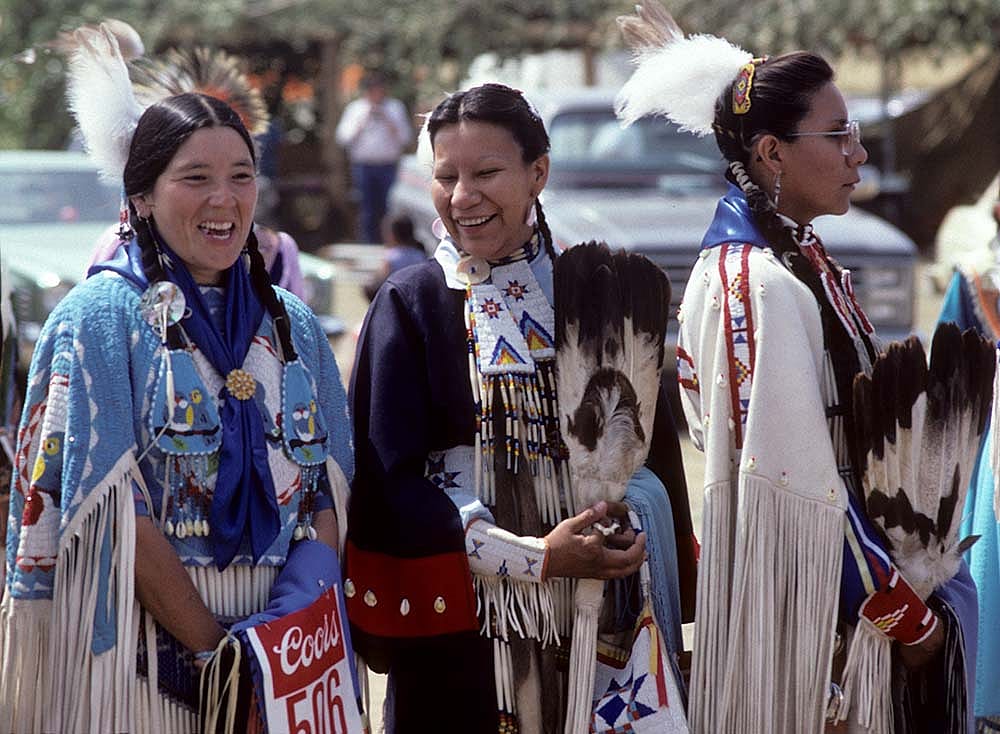

Dancing plays an integral role in the spiritual and social lives of Native peoples. This article examines contemporary powwows of the Northern Plains and a brief history of dancing among Dakota peoples. Prior to sustained Euro-American contact and coerced assimilation, Dakota peoples freely participated in a number of cultural practices where ceremony, honoring relatives, and socializing among one’s peers incorporated some form of dancing. Even today, many Dakota communities continue to refer to the “powwow” in the Dakota language as oskate (oh-SH’KAH-teh) “celebration,” or wacipi (wah-CHEE-pee) “dance.” The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (oh-YAH-tey), “people,” Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, University of South Dakota, and the Dakota peoples of the Fort Peck Indian reservation—to name only a few—all have annual celebrations that include wacipi or oskate in their titles.

Powwow

The word itself, powwow, has meaning and linguistic roots among the Narragansett peoples of the Northeast. Originally a word used to refer to holy men, the term changed and over time became synonymous with any gathering of Native people. Native peoples themselves use this term for their annual celebrations.

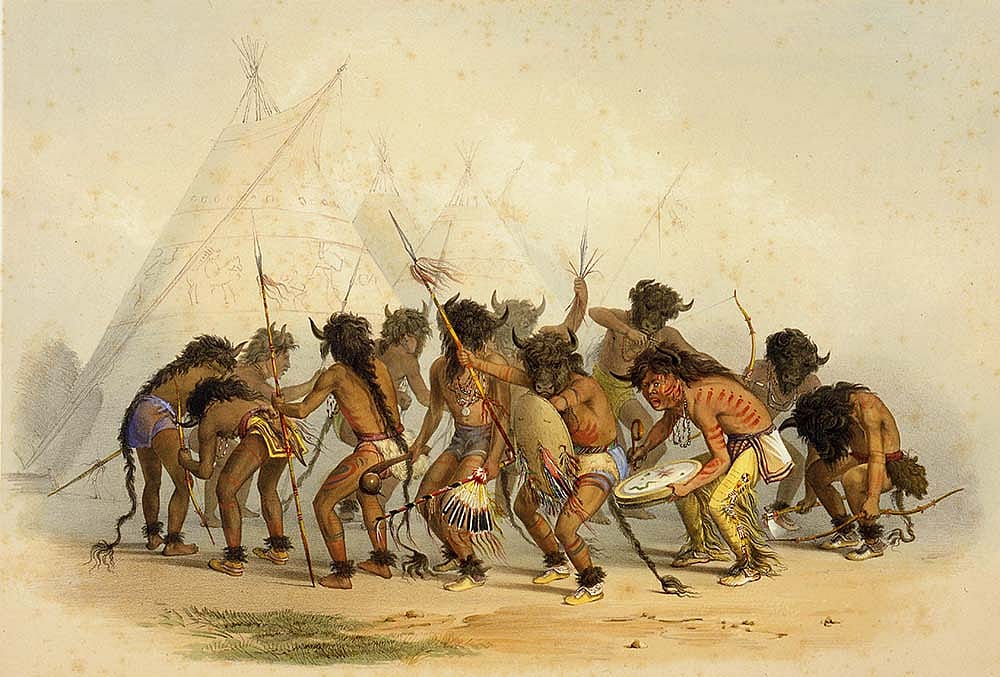

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, dancing could be found in both ceremonial and social settings. Honor was bestowed upon Dakota men through their participation in iwakci wacipi (e-WOK-chee wah-CHEE-pee) “scalp” dance. This dance is included among the numerous types of war dances; iwakci wacipi was a way for mothers and sisters to participate and sing songs of honor for their sons and brothers.

Social dances played an important role as they provided opportunities for young men and women to meet under the supervising eyes of older relatives. Today, many of these social dances continue as owl, rabbit, kahomani (gah-HOME-mahnee) “to turn,” and round dances. However, the practice of dancing is not just relegated to social gatherings; for many Dakota peoples, the Sun Dance (which will not be described here because of its sacred nature) continues to be practiced among many Dakota families and communities.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, off-reservation boarding schools and the policy of allotment were enforced as measures to assimilate Native peoples into American society. School officials replaced the social and cultural lessons of Native dance and ceremony with practices and values of the dominant society. By 1883, the United States government established Courts of Indian Offenses. These special courts targeted Native peoples who continued to participate in spiritual and cultural practices that stood in contrast to the practices of Christianity.

Eventually, authorities outlawed dances like the Sun Dance, and those who practiced them risked being charged and jailed. Wounded Knee, South Dakota, was one such case. Soldiers planned to disarm the Lakota there on December 29, 1890, before transporting them by train to the Pine Ridge Agency. Weapons fire erupted, and scores of innocent Lakota died in the wake of the attack on their culture and spiritual life—in particular, the Ghost Dance.

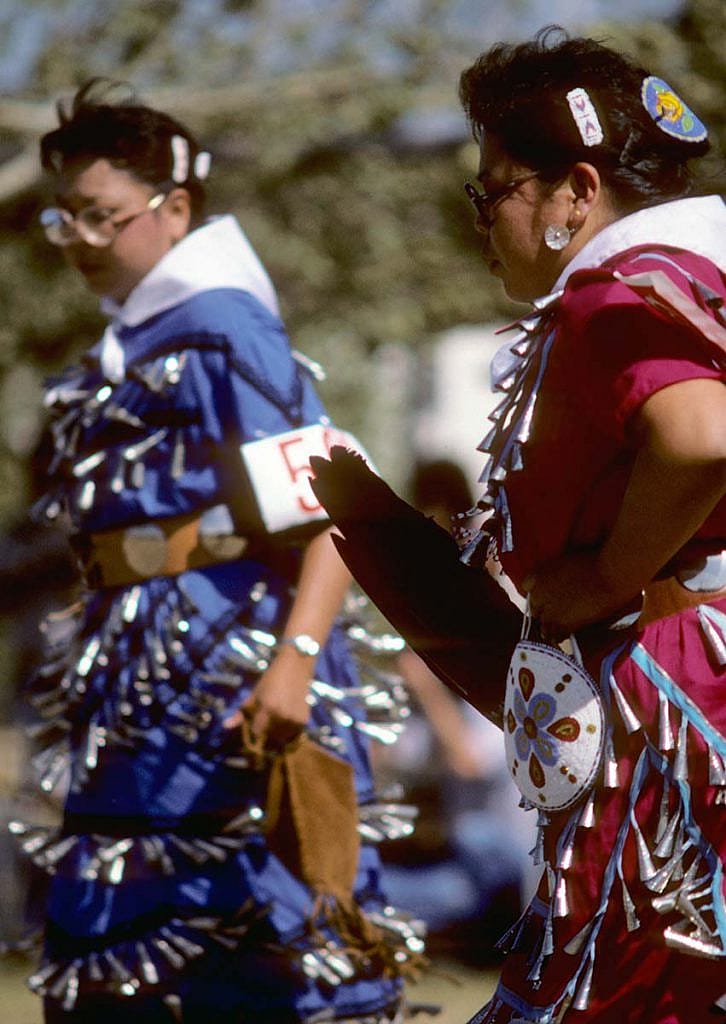

The massacre at Wounded Knee did not accomplish what it intended; Lakota and their Dakota allies continued their spiritual and cultural practices into the new century. Pre-reservation forms of dancing carried on, and new dances, like women’s jingle dress dance, were introduced to Dakota peoples. A holy man among the Mille Lacs band of Ojibway received the jingle dress and its accompanying dance in a dream. By the 1920s, the Annishinabe peoples at the White Earth reservation “gave” knowledge of the dress and dance to the Sisseton Sioux (Dakota), and from there it spread across Indian country. Today, numerous tribes across the U.S. and Canada participate in the jingle dress dance.

Cultural revitalization in the twentieth century

In the 1950s, tribal nations witnessed an era of federal policies that aimed to “terminate” their status as “domestic dependent nations.” Tribal nations like the Menominee (Wisconsin) and the Klamath (Oregon) became targets as officials deemed their abundant natural resources as evidence of their ability to join the market economy.

Alongside this policy of termination, the Bureau of Indian Affairs promoted a voluntary relocation program. This program sought to assist Native Americans in moving from rural and economically depressed reservation communities to cities and abundant job opportunities. Thus, individuals and entire families would live and grow up in urban cities that were far removed, both physically and culturally, from their tribal community.

Many criticized both the policy and program for their attempt to, on the one hand, circumvent treaty obligations, and on the other hand, remove Native Americans from their cultural moorings. However, relocation did not completely sever Native American cultural practices. A second, unintended outcome of relocation was that Native Americans began to socialize with each other. They gathered at Native American centers for social and cultural celebrations, creating unique intertribal communities and spaces.

As a result, Native American communities brought together their own specific tribal dances and practices. These social and intertribal dances are the foundation of the contemporary powwow. Many well-regarded powwows trace their origins to this era of revitalization: for example, the 1968 University of Montana’s Kyiyo Powwow in Missoula, Montana, and the Denver March Powwow, in Denver, Colorado, which began in 1974. Still, many places continued as before and strengthened their longstanding dance traditions in places like Sisseton, South Dakota, and among the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, whose annual celebrations can be traced back to the late 1860s.

The contemporary contest powwow

Many of today’s cultural celebrations take the form of contest powwows. These powwows, offering prize money, can draw anywhere from several dozen to several hundred dancers competing in numerous dance categories based on age and dance style. Large contest powwows—to name but a few—include, Crow Fair Powwow in Crow Agency, Montana; Northern Cheyenne 4th of July Powwow in Lame Deer, Montana; Mandaree Celebration in Manderee, North Dakota, and the annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow in Cody, Wyoming. All are well-known and well-regarded celebrations, and each draws hundreds of dancers and singers from across the United States and Canada.

In duration, a contest powwow can last all weekend. Typically most begin on Friday evening and continue through Sunday evening with the results of the contest winners being announced shortly upon the completion of the dance competition. The powwow weekend is organized around several “starts,” also known as Grand Entries, that signal the beginning of a dance session lasting several hours. Friday evening has a single Grand Entry, with Saturday separated into an afternoon Grand Entry, meal break, and evening Grand Entry. Depending on the organizing committee, Sunday can consist of one or two Grand Entries.

With each Grand Entry, a Native American veteran carries an eagle staff and leads into the arena a color guard of other Native Veterans or noted dignitaries each carrying flags of the United States; host tribal nation and state flags; and other significant flags, for example, flags representing veteran societies and organizations. Many Northern Plains powwows also include the flag of Canada, in acknowledgement of the many First Nations people who travel from their homes to participate in the celebration and those tribal nations whose ancestral homelands are divided by the U.S.-Canada international boundary line.

Following the color guard, powwow “royalty” enters the dance arena. Through a separate competition, these young women—and at times young men—have earned the right to represent their respective powwow and tribal communities, both while at home in their daily conduct, and while traveling to other powwows. Many of these young ambassadors have spent years honing their dance skills and cultural knowledge so that they can find success in the pageant competition. Their reign as an ambassador lasts only a single year before they pass on the title to the succeeding pageant winner.

Once the royalty has entered the arena, all participating dancers follow in order of their respective dance category. In general, the categories for men include northern traditional, southern straight, grass dance, and fancy feather while women’s categories include northern and southern traditional (at especially large powwows women in these two categories may be further divided into a cloth and buckskin subcategory), jingle dress, and fancy shawl. These dance categories are further separated by age groups to include golden age, senior, adult, teen, junior, and tiny tots.

Subsequently, during one or two powwow sessions, these dance categories and age brackets must dance an appropriate song or set of songs. This is also why it is not unusual for the gathering to end at midnight or in the early morning hours. Even large contest powwows are not solely focused on contest dancing. Throughout the powwow session, “intertribal” songs are meant for all to participate and dance. The announcer declares an intertribal dance and encourages spectators to come to the arena.

Organizers cannot hold a celebration if there are no drum groups in attendance. Each powwow committee secures a “host drum”—or even several host drums—to sing contest and intertribal songs throughout the entire weekend. For those unfamiliar with powwow music, it is worth noting that men engage in singing using specific Native words or “vocables” in which there are no words but sounds; never do these men chant. The difference between hearing selections sung rather than chanted is a matter of understanding Native music on Native terms versus western perceptions which can mischaracterize and misunderstand this cultural practice.

Singers and the drum are the backbone of any successful powwow. Oftentimes, there is a separate drum contest simultaneously judged using the songs sung for the dance contest. In this way, dancers are provided exceptional singing and songs appropriate to their dance style. The drum at the center of each group of singers is significant as it has its own spirit, and the beats it produces mirror that of a heartbeat calling on all to dance.

Powwow etiquette

Whether you are a first-time visitor or regular attendee of powwow celebrations, it is worth knowing or revisiting powwowing etiquette. Established powwows often have policies in place about commercial photography; it is important to check their website or poster for more information. If a policy is in place, the organizers of the powwow may require you to check in and register. All photographers, amateur or professional, who capture close-ups or body-length photos of individual dancers should ask and receive permission from the dancer before taking a photo. Images of participants dancing in large numbers or dancing in Grand Entry do not require permission from each individual dancer.

Throughout a powwow session, spectators and participants are asked periodically to stand and show respect for a flag or honor song. The announcer provides directions to the audience when these songs occur. For flag songs, men should also remove their hats. In addition, intertribal songs—many of which use vocables—are also an opportunity for spectators to participate in the powwow. Again, the announcer conveys to the audience when these intertribal songs occur and encourages everyone to join in. You do not need regalia (ceremonial clothing) to dance, nor do you need to be Native American to participate during these intertribal songs.

The immediate area surrounding the dance arena is reserved for tribal elders, dancers, singers, and their families. If you bring your chair, be mindful that the space around the arena is reserved for these individuals and empty chairs hold the place for powwow participants who come and go throughout the event.

Vendors are a key component of contemporary powwows; purchasing directly from powwow vendors supports Native American artists and Native-made artwork, and contributes to the overall success of the powwow. Contemporary powwows—for example, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow—even have specific guidelines for vendors to ensure that items sold are created by Native American artisans enrolled in a North American Indian tribal nation.

To be sure, dancing continues to play an important cultural and spiritual role in the lives of many Native Americans, and contemporary powwows are but one way that tribal nations express diversity, intertribalism, and innovation to the public.

About the author

An enrolled Dakota member of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, Dr. Majel Boxer is Associate Professor in the Department of Native American & Indigenous Studies at Fort Lewis College, Durango, Colorado. She received her doctorate in ethnic studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and in 2012, she was named one of 12 Emerging Scholars by Diverse: Issues in Higher Education magazine. In October 2016, Boxer received one of the Center’s Research Fellowships, working with Rebecca West, Curator of Plains Indian Cultures and the Plains Indian Museum. Boxer continues research on the “indigenization of the museum,” a historically western institution that Native American people have increasingly embraced in the last century.

Post 235

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.