James Bama’s Portraits of a People – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2015

James Bama’s Portraits of a People

By E. Crawford Wilson

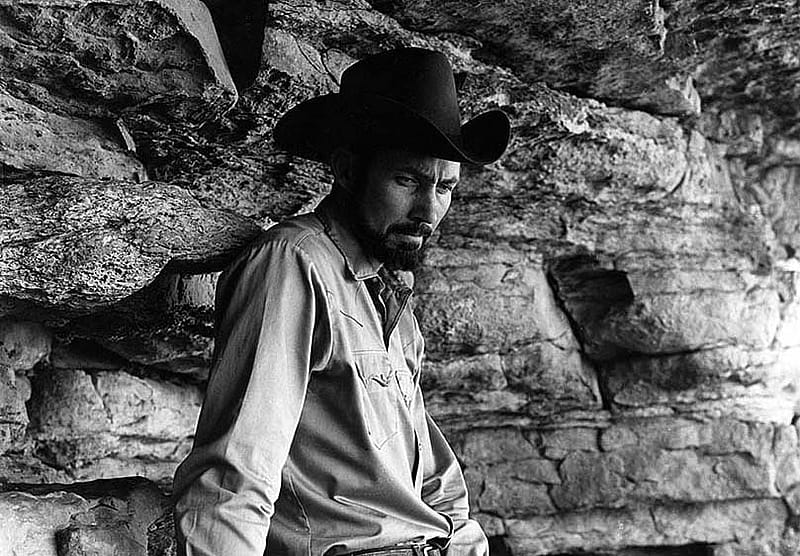

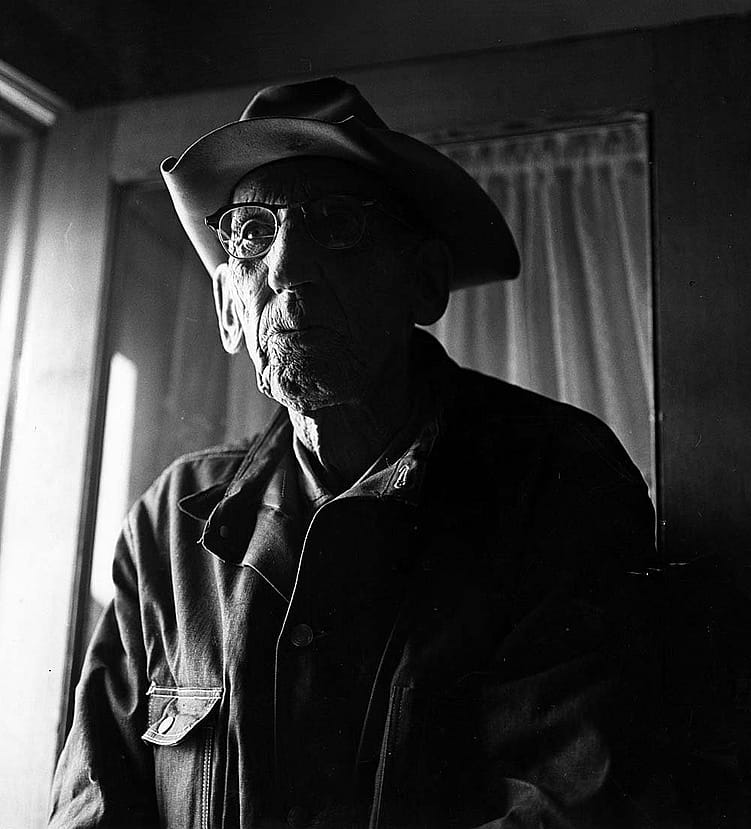

A myth of the West is that living here is eminently more real, gritty, and rugged than anywhere else in America. It is this myth that has regionalized a lifestyle—a lifestyle born of the open range, natural elements, and the hardscrabble people that built up the reputation of Wyoming. This is a land rooted in the “Forever West” of the American imagination. It was this West, and the people who populated it, that drew artist James Bama all the way out to Cody, Wyoming, in 1968, where his artistic wanderlust drove him to paint Wyoming’s history through the lens of its people.

James Bama made his reputation as a painter and illustrator, but he is equally as adept as a photographer, with a natural eye toward composition, technique, and capturing emotion. While shooting in the West, Bama’s exposure to his models ranged from brief encounters to prolonged photo shoots with a single subject for more than a decade. Having pored over hundreds of his photographs while putting together the second installment of Developing Stories: The Photography of James Bama, an [former] exhibition here at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, I have an untold appreciation for the skill with which he captures both the personality and human dignity of his subjects.

Bama photographed a wide variety of people as studies for his paintings—from rodeo clowns to cowboys, American Indians, and mountain man—but his favorite subject to capture was old timers. “I always wanted to paint old people, like Norman Rockwell did. Here I had this gold mine…all my childhood reminiscences of the history of the West,” he explained in his 2012 book with John Fleskes, James Bama: Personal Works.

This was a history, like all histories, that would slowly vanish into artifacts and books as generations of people came and went. Like many artists before him, Bama was determined to capture this older generation on canvas—and in photographs—as a way to document their lives and Wyoming’s state history before it too passed on.

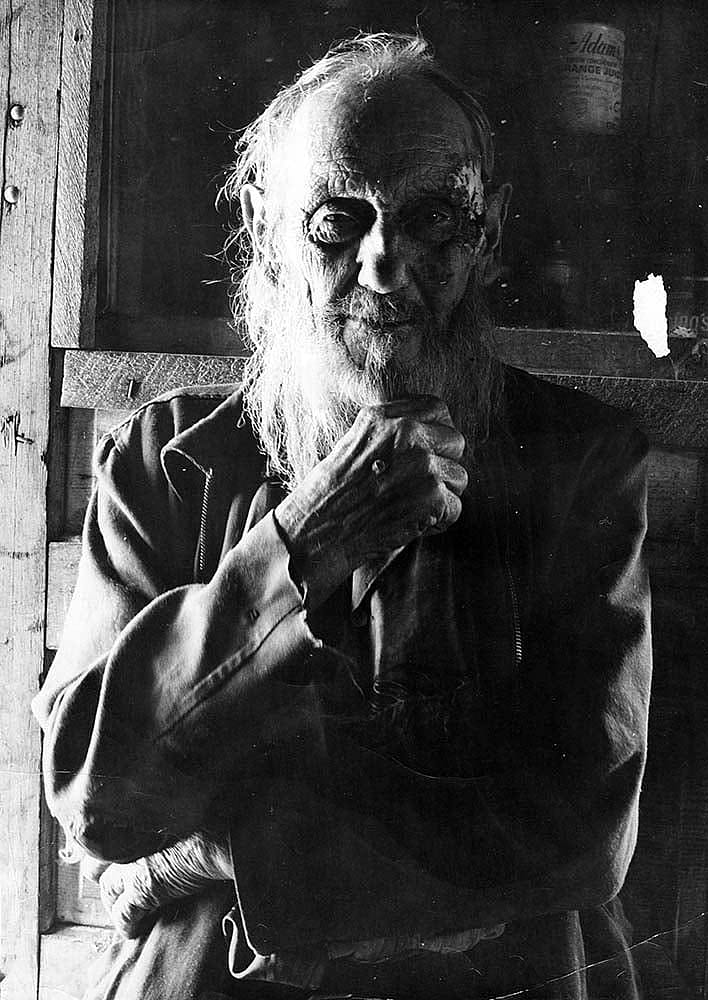

“Older people are almost like objects or still lifes. You can prop them up, but what can you do with a 94-year-old man? You can’t move him; you just can’t do very much with him. It is just enough to be able to sit up,” Bama told western art scholar and then Center of the West Director Peter Hassrick in 1976.

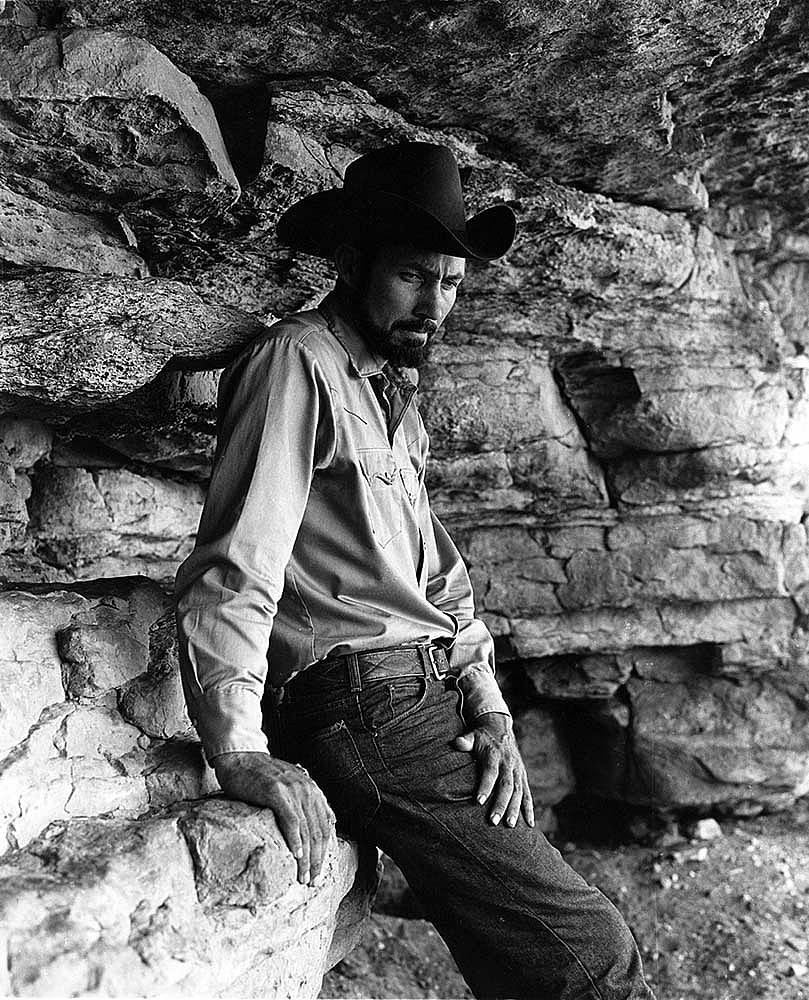

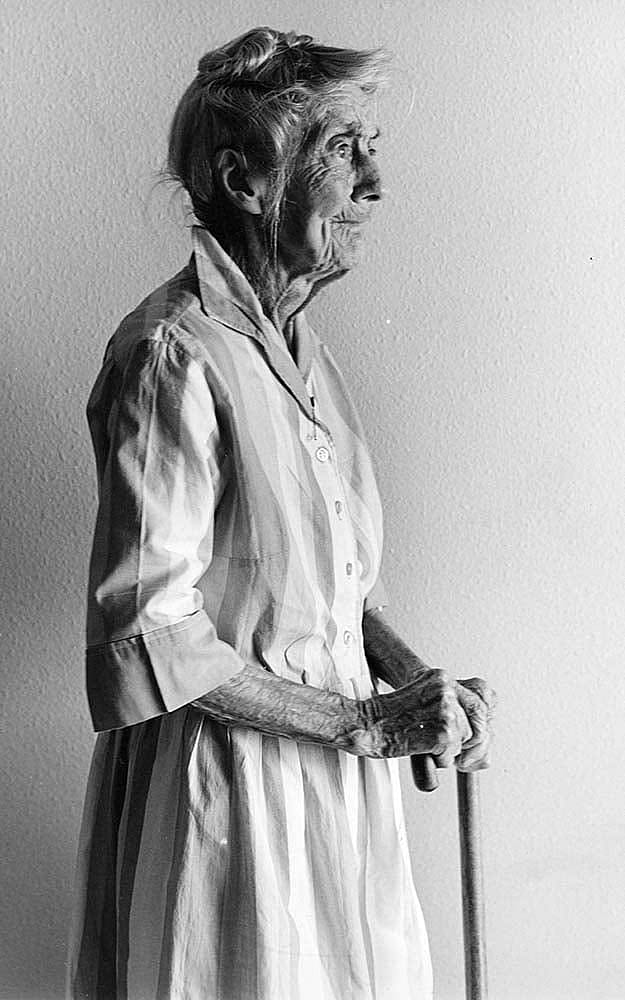

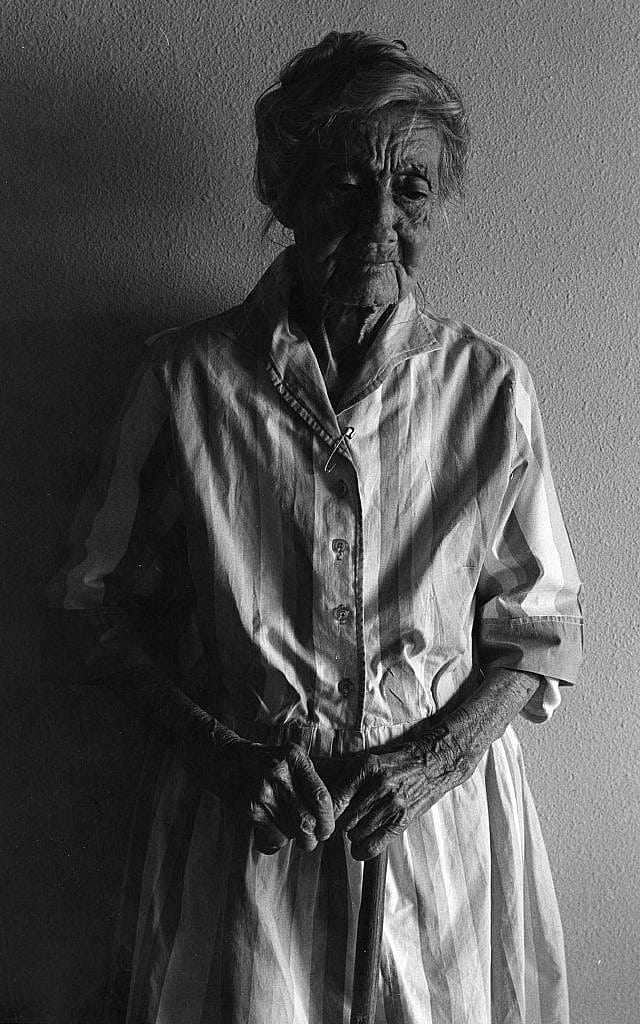

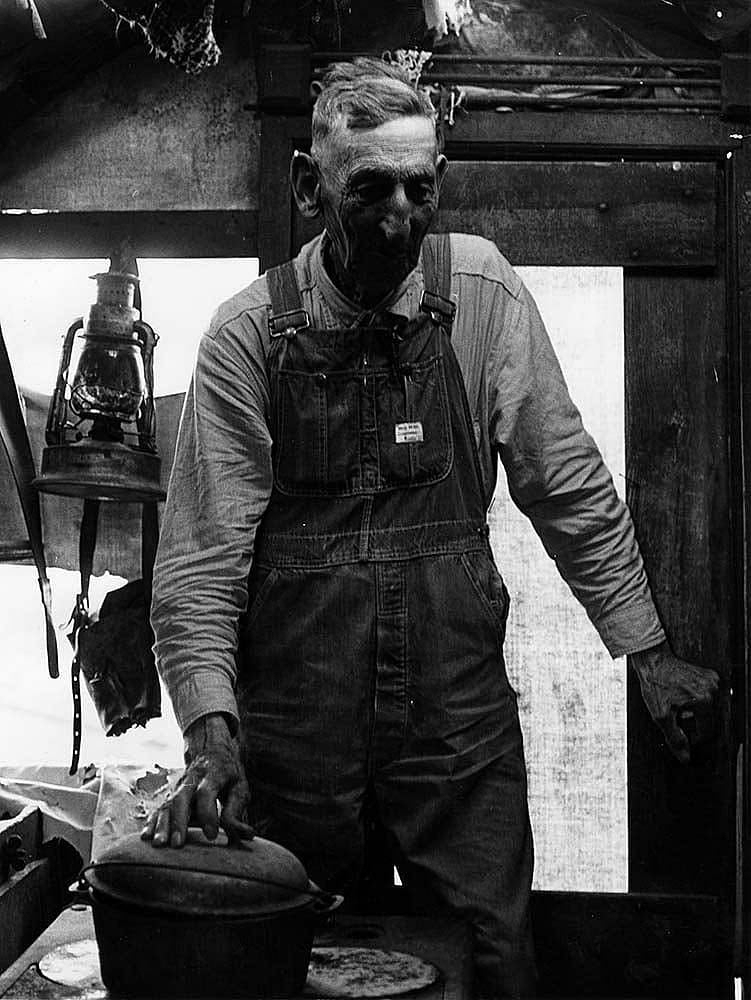

Having looked closely at Bama’s photographic series of portraits, I find that two images stand out. Echoes of one another in their artistic fingerprint, the photographs of Grandma “Emma” Slack, August 1971, and Roy Bezona, March 1970 are masterful examples of Bama’s ability to capture the delicate balance between the strength of character and the fragility of old age.

Bama captured the portraits of Slack in April and August of 1971, just two years before she died. Slack was born in 1875 on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, growing up in the shadow of the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 and the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. At seventeen, she fell in love with a stagecoach driver, married, and moved with him to the newly established Cody area.

Bama took the portraits of Roy Bezona in March of 1970 and 1971. Bezona was born the same day Wyoming became a state, July 10, 1890. He led a colorful life, full of odd jobs, from sheepherding to helping build the East Gate road into Yellowstone National Park.

Although, for Bama, older subjects offered less opportunity to give artistic direction, the simplicity of their poses allowed for a powerful transference of emotion. Bama captures the beautiful articulation of such emotion in the photographs of Slack and Bezona. They are perfect complements to one another in pose and sentiment. In these images, Bama masters the task of harnessing the formal elements of photography to evoke the stories of hardship, grit, and forbearance that come with old age and pioneering the settling of the West.

The play of light and shadow creates an ambiance of introspection and loneliness in the bodies of Slack and Bezona. Deepened shadows along each of their faces provide an air of mystery, hiding the wrinkles etched in their skin and recalling both the obscurity of memory and the fate of the aged. In Slack’s photograph, the dual lighting creates a softened profile, giving her a more delicate look, while the harsh light that frames Bezona’s body generates a sharp contrast, allowing him to stand out among the numerous objects interspersed within the background.

Bama’s careful consideration of lighting and pose allowed him to imbue both subjects with dignity and the appearance of strength. His use of shadow, not only creates atmosphere, but functions to mask the show of effort required for Slack and Bezona to pose. By placing Slack against a wall, Bama straightens her posture, which allows for a looser grip on her cane. He achieved Bezona’s confident pose through the counterbalance created between opposite sides of his body. A loose right arm and a light touch on the cast iron pot provide the perfect foil to a tension-filled left side, a balance that allows Bezona to stand without his customary cane.

The achievement of simplicity in these images is due to Bama’s artistry and direction, as much as it is a reflection of the demeanor of his subjects. As models, Slack and Bezona presented themselves in true form. Their modest dress and clean appearance are hallmarks of the simple lifestyles they led as early western settlers and continued to lead in contemporary times. Bama’s ability to suggest and present all these elements of his sitters’ personalities on film is not only a testament to his skill as an artist, but to his innate understanding of people.

Renowned nineteenth-century portrait photographer Nadar (the pseudonym of Gaspar-Félix Tournachon) once declared, “one [cannot] be taught how to grasp the personality of the sitter. To produce an intimate likeness rather than a banal portrait…you must put yourself at once in communion with the sitter, size up his thoughts and his very character.” This sentiment courses through all of Bama’s portraits, and even the untrained eye can discern it—from the simple strength and tired eyes of the worn-out cowboys to the eager joy of children on parade.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.