Art of the Battle of Little Bighorn – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2010

Truth, Myth, and Imagination: Art of the Battle of Little Bighorn

By Christine C. Brindza

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum’s collection contains work depicting the Battle of Little Bighorn—several paintings, prints, and sketches offer a glimpse into those fateful days in the summer of 1876. Here, former Whitney Curatorial Christine Brindza conveys some of the ways the battle has been interpreted through art.

Variously called the Battle of Little Bighorn, the Battle of Greasy Grass, Custer’s Last Stand, Custer’s Last Fight, and several other names depending on cultural and historical perspective, the Battle of Little Bighorn remains shrouded in mystery. Since the date of the battle, June 25–26, 1876, this event in U.S. history has captivated the American public. More than 263 members of the United States Seventh Cavalry, under the leadership of George Armstrong Custer, fought Lakota and Cheyenne Native Americans in southeast Montana and perished. As early as two weeks after the battle, artists attempted to recreate the mysteries of the battle in newspaper illustrations and major-scale works on canvas.

Some of these early artists served as historians, whether intentionally or not, revealing details of the battle in their work. Others merely created a work of art based on imagination. Regardless, as the public saw these early images, their views of the battle were shaped by the artwork, and therefore, helped create myths and legends that resonate even today.

Historical accuracy has plagued the Battle of Little Bighorn for well over a century. Numerous accounts from all sides of the battle were recorded, including warriors involved, soldiers first at the scene after the battle, and witnesses of the battle. Research continues to develop new accounts of what really happened that summer in 1876, but no one can be certain. Artists choose their own version of history to create in their work.

The public sees the first images of the battle

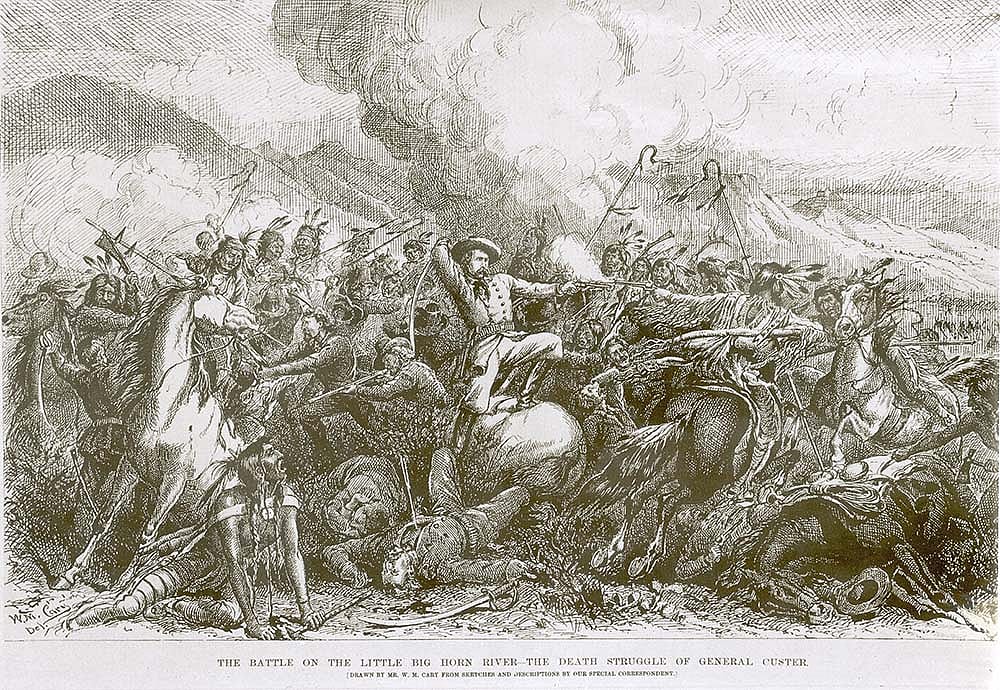

Artists provided incorrect information about the battle that was sometimes mistaken for truth. For example, William de la Montagne Cary (1840–1922), captured the imagination of the public in his The Battle on the Little Big Horn River—The Death Struggle of General Custer, which appeared in the New York Daily Graphic and Illustrated Evening Newspaper on July 19, 1876. This was among the first renditions of the event seen by the general masses.

Cary’s work aided in establishing the image of a heroic “last stand” which the public believed. Here, Custer is the central figure with a saber in his right hand, a revolver in his left. Actually, there were no sabers carried by Custer or his men at the battlefield that day. Interestingly, the original caption under the image reads that it was drawn “from sketches and description by our special correspondent.” This illustration, inaccuracies included, set the standard of images to follow.

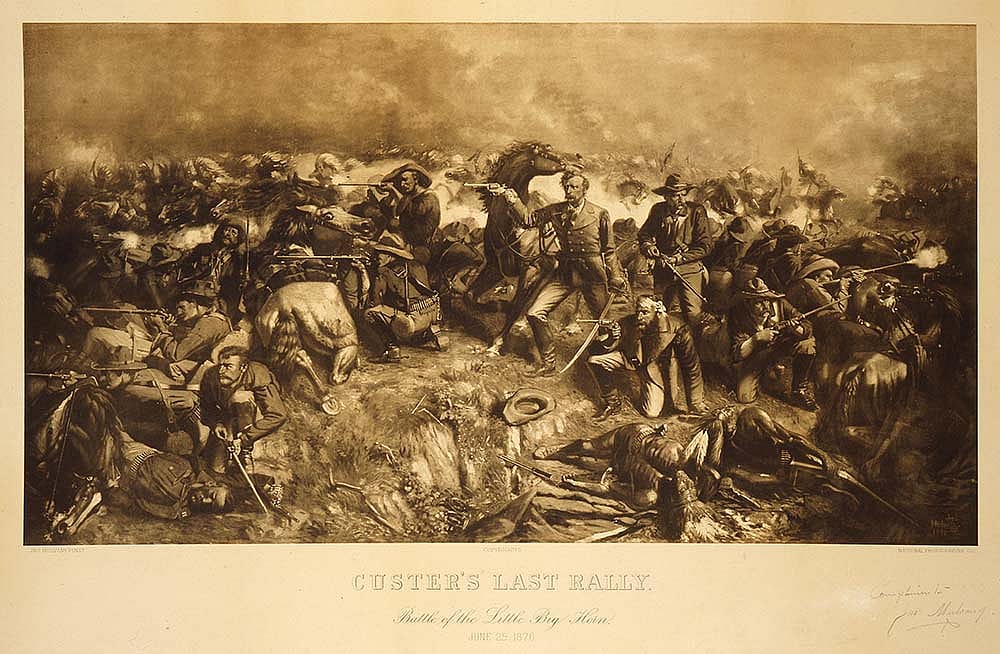

At the end of the nineteenth century, John Mulvany (1844–1906) portrayed Custer as the focal point in Custer’s Last Rally. The artist visited the battle site in 1879, made sketches of the terrain, and visited the Lakota on the reservation. He created a painting measuring twenty by eleven feet, taking two years to complete it. Mulvany’s work received much praise. A review from poet Walt Whitman stated, “…the whole scene, inexpressible, dreadful, yet with an attraction and beauty that will remain forever in my memory.” Later Mulvany painted a smaller version, which was reproduced as a photogravure, or print, one of which is in the collection of the Buffalo Center of the West.

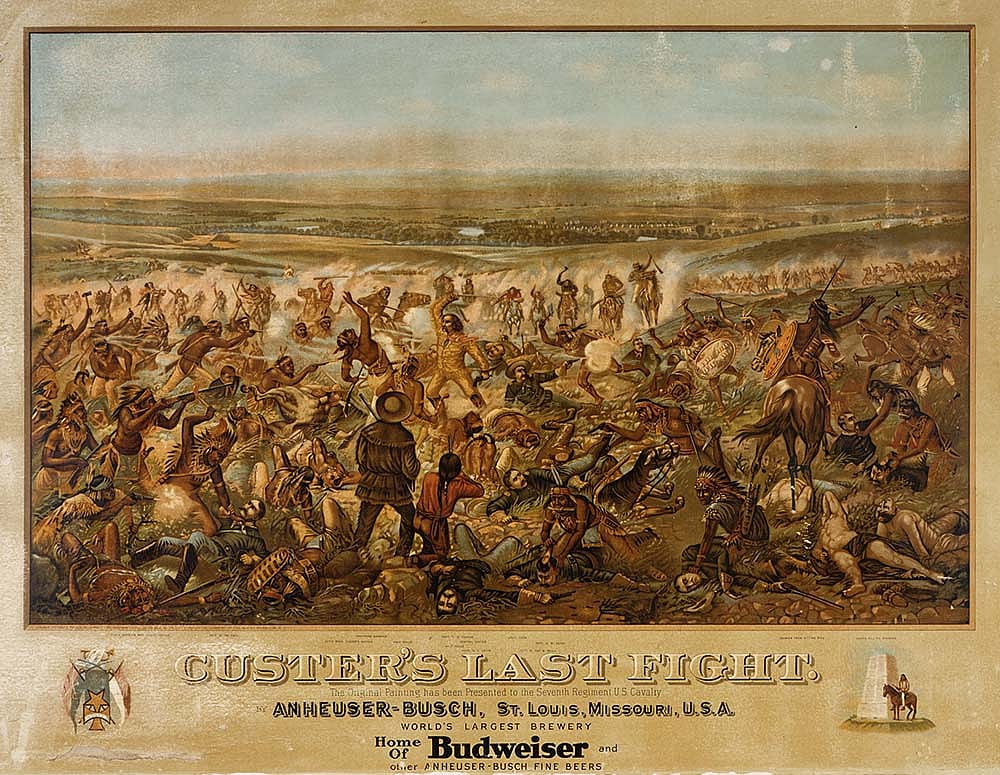

Cassily Adams (1843-1921), artist. Otto Becker (1854-1945), lithographer. Custer’s Last Fight, 1896. colored lithograph, 31.125 x 41.75 inches. Gift of The Coe Foundation. 1.69.420B

John Mulvany (1844-1906). Custer’s Last Rally, 1881. Sepia toned photogravure, 20.5 x 32.375 inches. Museum Purchase. 149.69

One of the first depictions of the battle was William de la Montagne Cary’s, “The Battle on the Little Big Horn River–The Death Struggle of General Custer,” Daily Graphic and Illustrated Evening Newspaper, New York, New York, July 19, 1876. Don Russell Collection. MS62.1.O.3.27.01

Another unlikely source promoted the imagery of the Battle of Little Bighorn: the Anheuser-Busch Company in St. Louis, Missouri. This company produced a lithograph of Custer’s Last Fight, credited to Cassilly Adams, artist (1843–1921) and Otto Becker, lithographer (1854–1945).

Adams first painted the original work in 1885. He used Lakota Indians as models in battle dress and U.S. cavalrymen in uniforms of the period, and based his image on the accounts available at the time. The painting originally included two side panels depicting fictional events in Custer’s life, but those are now lost. The artist wanted to present the painting to the U.S. government as a historical record after the work toured the country, but that never occurred.

Adams’s painting was sold to a bar owner who displayed the work until one of his creditors, the Anheuser-Busch Company, obtained the painting as debt settlement. Adolphus Busch was interested in the subject of the Battle of Little Bighorn and found the painting intriguing. Thinking he could market the image, he hired Otto Becker’s Lithographic and Engraving Firm of Milwaukee to create a version of Adams’s painting. Becker reworked the composition, making some changes in scenery, and the figures of Native Americans and cavalry. The lithograph was given to every bar that sold Bock beer, but even bars that did not sell the product obtained copies because of its growing popularity. It is estimated that 150,000 copies of the lithograph were distributed across the country during its first runs.

In 1895, the Seventh Cavalry possessed the original work by Adams. Unfortunately, the painting was moved from fort to fort, and all the while was severely neglected. The painting found a more permanent home in the Seventh Cavalry officer’s club building at Fort Bliss, Texas, from 1938 until 1946, where, sadly, it was destroyed by fire. The lithograph went on to become among the most recognizable of Battle of Little Bighorn depictions.

Native American painted hide

The Battle of Little Bighorn is viewed differently by Native Americans than by Euro-Americans. The most popular battle depictions were usually by male Euro-Americans. Recently, however, artwork based on Native American accounts has gained more recognition. Artistic representations from Native American people show a distinctive angle of the event never before explored—or previously ignored.

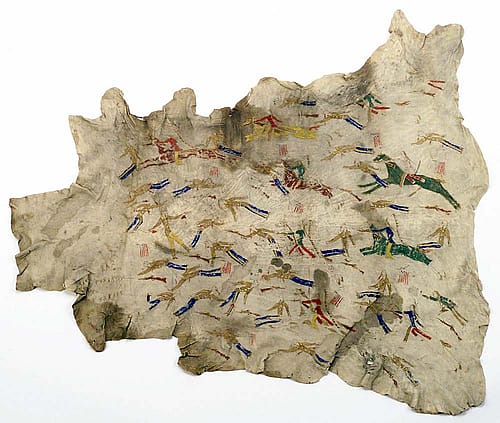

Native American Plains Indians painted hides, often made of deer or bison, with natural pigments found from the environment. In her book Memory and Vision, Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian Peoples, Buffalo Bill Center of the West Plains Indian Museum Curator Emerita Emma I. Hansen wrote, “Men recorded their accomplishments in hunting and warfare through paintings on hides, tipi liners, tipi covers, and their own shirts and leggings.” Such paintings were accompanied by storytelling of oral histories. The hides, tipis, and clothing sometimes depicted warriors engaged in battle or a particular event of the tribe. Individuals represented can be identified through specific clothing or features such as hairstyles or accessories; some remain anonymous.

A tanned deer hide from the Plains Indian Museum collection, dating to the late nineteenth century, shows a battle scene between Native Americans and U.S. Army soldiers—an account of Custer’s famous Last Stand. The painted hide is of Lakota origin. Warriors are both on foot and on horseback; the soldiers are dressed in blue and yellow uniforms. Custer, a soldier with yellow hair and wearing buckskin, stands armed with two revolvers at center left.

Depictions by Plains Indians from following the Battle of Little Bighorn were not published or as widely available as the Euro-American accounts. More recently, these views have gained more attention because of the vital perspective presented. Accounts of the battle recorded on hides are thought to be truer records of history, though the oral histories were sometimes lost or misinterpreted over time.

Paxson’s version

Edgar S. Paxson’s Custer’s Last Stand, finished in 1899, became one of the best-known images of the event, both glorifying the battle and creating a so-called martyred Custer. The oil on canvas is a large-scale history painting, a narrative of the event thoroughly researched.

Born in East Hamburg, New York, Paxson (1852–1919) moved to Montana about a year after the Battle of Little Bighorn. The artist was engrossed by the event and decided that someday “‘I will paint that scene…’ during my leisure hours. I kept dabbling with brush. Each day I saw some improvement.” He was determined to paint the scene as accurately as possible and said that he, “…for twenty years gathered data, sifted and resifted it, conversed with participants on either side, visited the scene and became as familiar with the ground and the circumstances as with my own home.”

Paxson also interviewed ninety-six soldiers from the related campaign and contacted Edward S. Godfrey, a Lieutenant in Captain Benteen’s force who saw the scene after the battle. In addition, Paxson interviewed Plains Indian leaders involved with the confrontation and visited the battle site several times. Among his friends were Rain-In-the-Face, Gall, and Sitting Bull.

Creating many preliminary sketches for his Custer’s Last Stand, Paxson worked and reworked the figures he incorporated into his final canvas. The Whitney Western Art Museum collection has several of these sketches on display throughout the summer, along with some personal items that belonged to Paxson, such as paint brushes and other artist tools.

The final version of Custer’s Last Stand is a densely-packed canvas that shows action and drama—much derived from the artist’s imagination. It includes more than two hundred figures and at least twenty-five portraits. The painting traveled to numerous places for display and resided in Montana before it found a permanent home at the Center in 1969. It has fascinated viewers from its first debut to the present, where it is on display in the Whitney Western Art Museum.

Battle of Greasy Grass

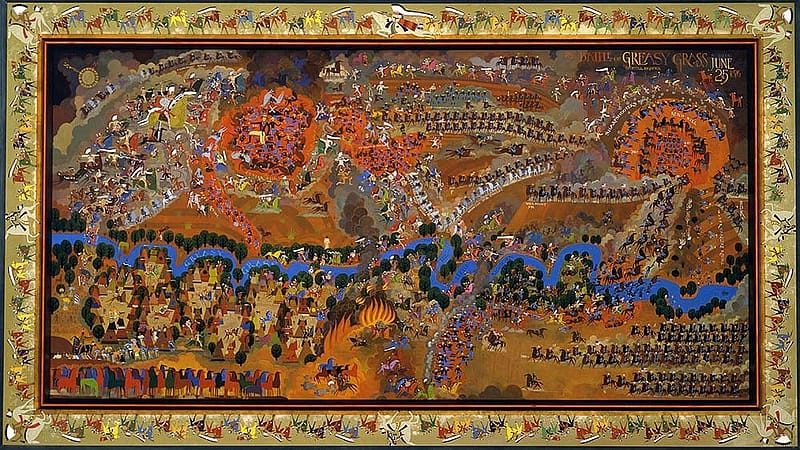

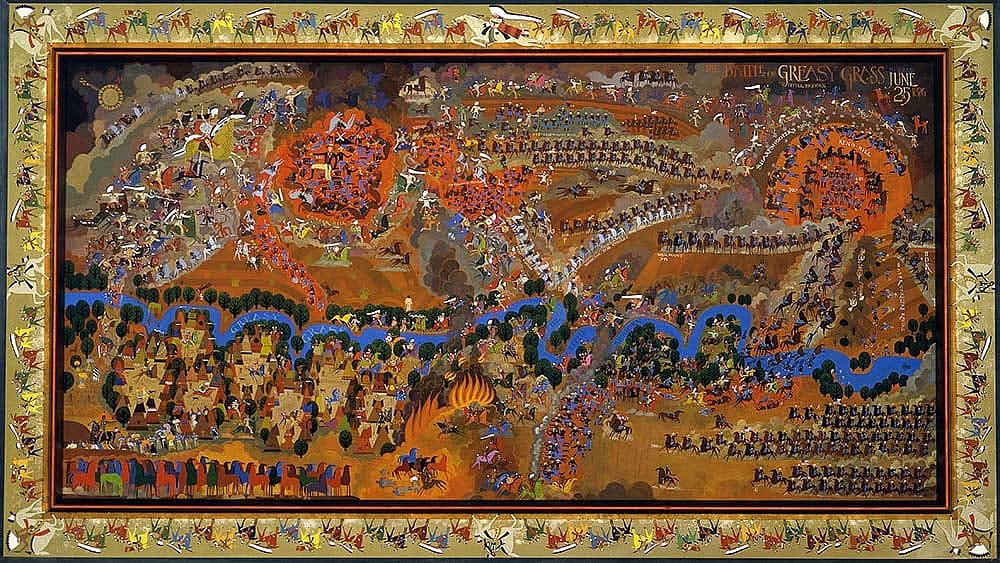

Allan Mardon (b. 1931) completed The Battle of Greasy Grass in 1996, portraying Custer’s “last stand” from a contemporary context, using Native American accounts of the battle. Mardon, a non-Native American, created his work to be “historically accurate,” but in accordance with a modern, Native American perspective.

Mardon chose a significant title for his work. The Battle of Greasy Grass is the Lakota title for the famous battle named after the waters by the battle site—the Greasy Grass. It is also known as the Little Bighorn River. Using the Native American name for the battle clearly demonstrates what account the artist followed. Mardon incorporated a twenty-four hour period onto one painting, giving hourly accounts of points during the battle, beginning at 3 p.m. June 25 until 3 p.m. June 26, when Sitting Bull called back his warriors. It took one year for Mardon to research the battle and one year to paint the large scale oil on linen. He also created the intricate frame for the piece.

Using the directions given by the battle’s participants and witnesses, Mardon inserted locations of specific events related to the conflict. After the battle, there were problems in determining locations and directions from both soldier and Native American accounts. Mardon addressed this issue by placing a compass in the upper left corner of the painting, signaling two Norths. The Native American warriors guided themselves by the position of the sun, moon, and the stars; soldiers judged direction by magnetism of the North and South Poles.

In The Battle of Greasy Grass, Mardon included individuals mostly ignored or unheard of in other battle representations. Though he did paint Custer and other well known people, Mardon incorporated others such as Kate Bighead, a Cheyenne woman who witnessed the battle from a distance. He also included Mark Kellogg, a reporter from the Bismarck Tribune, who was killed during the battle. Kellogg is shown with scattered papers alongside his body, symbolizing how the account he may have written was forever lost. An African American present at the battle is in Mardon’s work as well—the scout, Isaiah Dorman, who also perished at the scene. Mardon broke away from the accepted ideology of the Battle of Little Bighorn, shedding new light on an old story.

Contemporary Native American artists

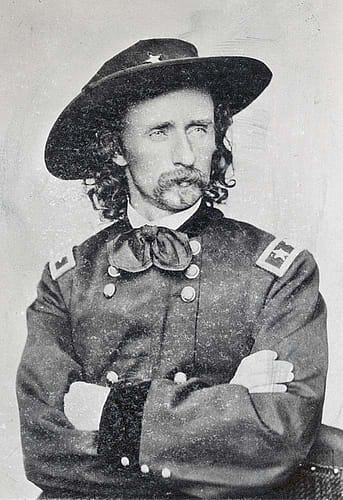

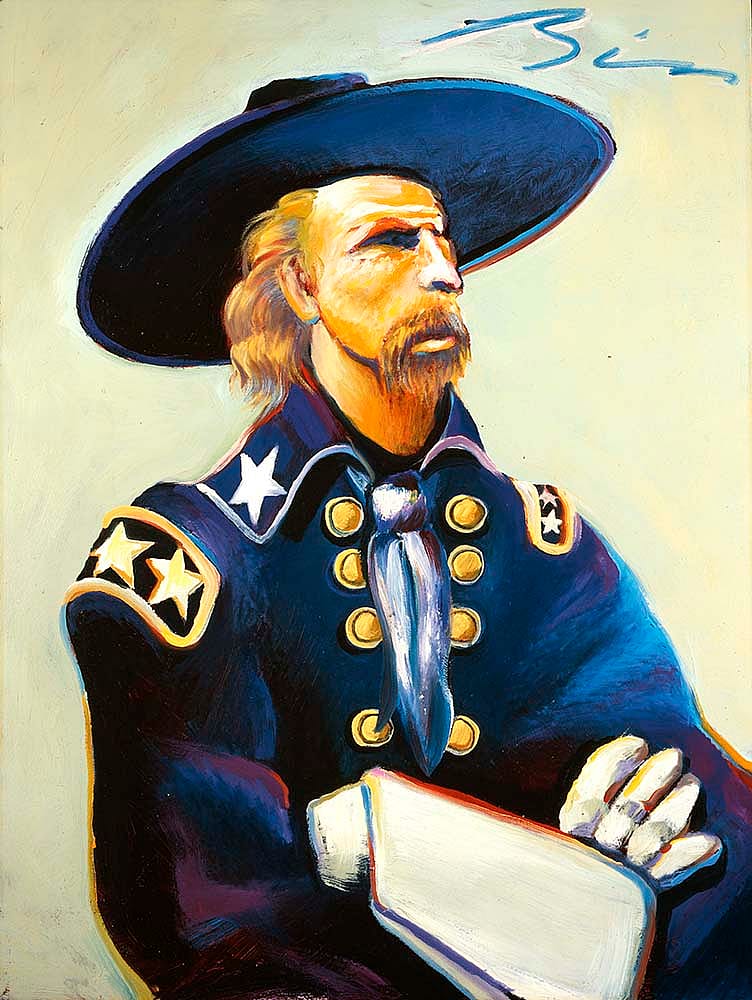

Earl Biss (1947–1998), artist and member of the Crow nation, focused not on the battle, but on the most well-known individual from the battle, George Armstrong Custer. Biss, a renowned abstract expressionist, conveyed emotion through color and line in the portrait General Custer in Blue and Green, 1996, using strengths from both his cultural background and artistic training. He looked for inspiration from the past and his cultural experience, but brought it into a contemporary context.

Fritz Scholder (1937-2005). Custer and 20,000 Indians, 1969. Oil on canvas, 29.75 x 40 inches. Gift of Janis and Wiley T. Buchannan III. 7.08

Fritz Scholder. American Landscape, 1976. Lithograph on paper, 30 x 22.5 inches. Gift of Jack and Carol O’Grady. 10.00.4

Earl Biss (1947-1998). General Custer in Blue and Green, 1996. Oil on canvas, 39.875 x 30 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Israel of Aspen, Colorado. 18.00

Biss was the great grandson of White Man Runs Him, a Crow who was hired to track the Lakota for Custer. Therefore, the artist had a personal connection with those he painted. Biss was strongly influenced by the photograph of Custer taken by Matthew Brady on May 23, 1865, known to be Custer’s favorite portrait of himself. The Battle of Little Bighorn is not the subject of this painting; it is of Custer alone, who for years was involved in the lives of Biss’s people. Biss feeds into the myth of the Battle of Little Bighorn through the man whose actions during the battle are still controversial.

Luiseño artist Fritz Scholder (1937–2005), combined two famous Battle of Little Bighorn images and made significant commentary to deep-seated historical views. In his Custer and 20,000 Indians, completed in 1969, Scholder referenced the early historic newspaper illustration by William de la Montagne Cary, The Death Struggle of General Custer, and took it a step further. The central figure in Cary’s image was of Custer, and to emphasize that focus, Scholder eliminated any other figures surrounding Custer in his work. The field of black with scarlet slashes in the background represents a mass of Native American warriors. Custer appears to be combating them single-handedly, enhancing the perception of Custer’s martyrdom. Scholder gave a modern, satirical twist to the event, meant to provoke thought.

In 1976, the centennial anniversary of the Battle of Little Bighorn and the bicentennial of the United States, Scholder created his own version of Paxson’s Custer’s Last Stand. He understood the popularity and significance of this painting and produced his own rendering of it titled American Landscape. As a counterpoint to Paxson’s famous painting, Scholder reversed and distorted the original Paxson scene, recreating it in black and white, thereby altering the myth surrounding the event itself. Scholder wanted to draw attention to how the battle and Custer have been permanently affixed to the American psyche and the American landscape.

The Battle of Little Bighorn today

From William de la Montagne Cary and Edgar S. Paxson to Fritz Scholder and Allan Mardon, art representing the Battle of Little Bighorn evolved in many forms. When news of the event first reached the public in 1876, the emphasis was on getting imagery to the masses, often at the expense of accuracy. The conflict and persons involved were viewed much differently than today. In contemporary times, though, artists are able to develop a more comprehensive perspective, tapping into well-established historical resources from multiple viewpoints.

Clearly, the Battle of Little Bighorn still resides in American public consciousness. When one examines the numerous perspectives of this event, both past and present, it can be better understood. In the same way, if we can better comprehend our past, we may learn and understand more about each other.

About the author

At the time this article was written, Christine C. Brindza served as the Acting Curator of the Whitney Western Art Museum. She curated the exhibition Curator’s Choice: The Art of Frederic Remington. She completed work with the curator on the Whitney’s 50th Anniversary Celebration in June 2009 which included a full reinstallation, publication, and celebratory events. At the same time, she spearheaded two special exhibitions: An Artist with the Corps of Discovery: One Hundred Paintings Illustrating the Journals of Lewis and Clark, Featuring the Artwork of Charles Fritz and To the Western Ocean: Paintings Depicting the Members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In 2008, Brindza shared her research in a presentation to the Custer Battlefield Historical Museum Association Symposium in Hardin, Montana. She has a Master of Arts degree in Archival, Museum, and Editing Studies and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Art History from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Post 242

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.