Celebrating the First 50 Years of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2009

Celebrating the First 50 Years of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art*

*Ed. note: the Whitney Gallery of Western Art was renamed the Whitney Western Art Museum in 2013.

The Whitney was completely redesigned and reinterpreted in 2009, so now in 2019 we share this article from 10 years ago, written just before the new design was unveiled in June 2009.

By Mindy A. Besaw

Fifty years ago, in the winter of 1959, the small town of Cody, Wyoming, buzzed with excitement as it anticipated the opening of the brand-new Whitney Gallery of Western Art. From a distance, and with great curiosity, residents watched the construction of the building on the edge of town near the monumental sculpture Buffalo Bill—The Scout. One March afternoon, they witnessed an eighteen-wheel semi-truck back up to the building’s entrance, and workers unload large crates directly into the gallery. What would the museum be like when it opened? Would it have an impact on Cody? Would it have national and international impact as well?

The Whitney Gallery of Western Art was one of the very first museums to feature art of the American West, and its opening in April 1959 did indeed garner national and international attention. Ever since its inception, the Whitney gallery has led the art world with outstanding collections, cutting-edge scholarship and exhibitions, and topnotch programs. Now, as we look forward to the Whitney Gallery of Western Art’s 50th Anniversary celebration this summer, it is a good time to reflect on and celebrate our first fifty years.

The Whitney gallery opened to the public with much fanfare and excitement on April 25, 1959. Three thousand fascinated, excited people poured through the doors of the Whitney gallery to see for themselves just what had been created—not bad for a town of less than 5,000 residents. Reporters flocked to Cody from the east coast, the west coast, and regions in between. Movie stars, political figures, and artists peppered the crowds, and everyone raved about the success of the opening. The building was constructed from all the best materials including terrazzo flooring, and redwood paneling on the walls, not to mention the finest western American art anyone had ever seen. However, the story of “the Whitney” began decades earlier.

Remarkable patrons…

Long before the Whitney opened, the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association commissioned a New York artist, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, to create a monument to Buffalo Bill. Mrs. Whitney turned out to be the perfect choice: Not only did she create a monumental masterpiece, she also gave generously. In 1924, she donated Buffalo Bill—The Scout, and forty acres of adjacent land, to the memorial association. The town overwhelmingly expressed their appreciation and enthusiasm—its size tripled when an estimated 5,000– 6,000 people attended the dedication of the Scout on July 4, 1924. Mrs. Whitney’s striking monument was only the beginning of the Whitney legacy in Cody.

For thirty years, the Scout remained solitary at the outskirts of town. Then, in 1954, the memorial association’s dreams for a new building moved closer to reality. Five years after his first visit to Cody, Gertrude’s son Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney donated $250,000 to the memorial association in his mother’s memory. Planning for the new building then began in earnest.

The Whitney Gallery of Western Art would be constructed across the street from the existing Buffalo Bill Museum on the land Mrs. Whitney, its namesake, had donated. Since the trustees of the memorial association knew they wanted to enhance the site of Buffalo Bill—The Scout, the plans were drawn with large picture windows facing the memorial. Once the proposal was approved in 1957, construction would begin right away, and before it was finished, Mr. Whitney donated an additional $250,000 to complete the building.

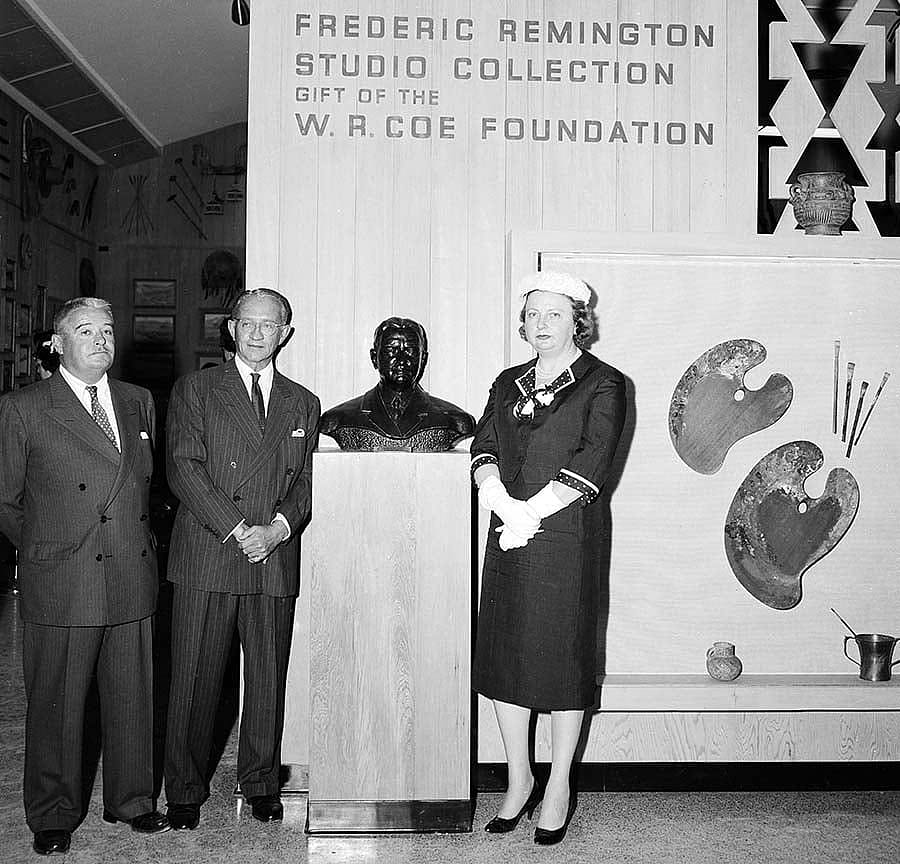

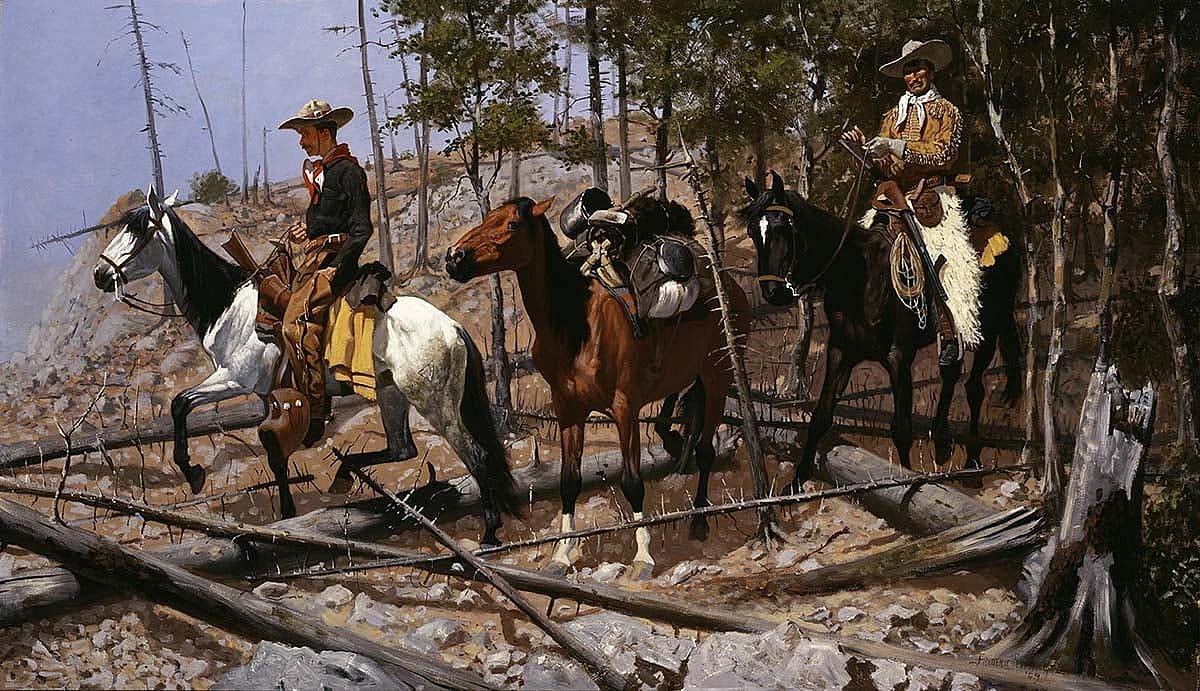

Yet, Mr. Whitney’s generous gift was not the only impetus for a brand new building to house western American art. In 1957, the Honorable Robert Coe, acting for the Coe Foundation, purchased the Frederic Remington studio collection of paintings, sketches, and artifacts, and donated it to the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association. There was only one stipulation: A new building had to be constructed to showcase the collection.

The Coe Foundation purchase of the Remington studio collection was not without notice. In November 1957, the New York Times announced that, “An enormous collection of oil sketches and relics that came out of the last days of the Old West is going to Cody, Wyo., home of the last of the great Western scouts, Buffalo Bill.” They were right—the collection is massive, both in quantity (110 oil sketches and nearly 400 studio objects) and in importance since Remington was one of the greatest artists to depict the American West.

As the Whitney gallery construction neared completion, and some artwork was secured to place inside, the board of trustees recognized that they were still lacking one thing—a new leader for the gallery. To match the high-quality art and ambitious goals of the Whitney, they looked for someone with knowledge of and a reputation in western American art. This was not an easy task. In the 1950s, western American art was still a growing field with very few scholars and specialists, and even fewer enthusiasts and champions of the art, especially in the East.

Dr. Harold McCracken had that good reputation, deep interest and knowledge of the subject, and connections with galleries and collectors that the trustees were seeking. McCracken was an outdoorsman, naturalist, explorer, writer, and, most importantly, a recognized authority on artists of the American West. McCracken had written the definitive biography of Frederic Remington and had published many other books on western American art at a time when no one else was writing about the subject. McCracken led the interest in art of the West on a national scale and was the strongest candidate for founding director of the Whitney gallery.

On January 19, 1959, McCracken’s first day on the job, he faced quite the challenge: an empty gallery and an opening date only four months away. In his autobiography, McCracken described the gallery: “The building was as bare as a railroad tunnel, and its 240-foot long gallery looked as big as Grand Central Station early on a Sunday morning.” Nevertheless, with the assistance of William Davidson from Knoedler Galleries in New York, McCracken assembled a grand opening exhibition worthy of the new museum.

The grand opening…

On April 25, 1959, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney proudly dedicated the new museum in his mother’s name. He declared that the museum “will help swing the tide to a greater appreciation of America’s cultural achievement by presenting western art at its best.” National newspapers echoed Whitney’s enthusiasm. A glowing review in the Los Angeles Times boasted, “The most important exhibition of western art ever to be assembled in one place opened here this afternoon…” The Times predicted the Whitney would achieve international importance, not only as the unique archive of American history, but also as a fine art museum. Further, they encouraged readers to visit, saying, “Anyone planning to travel to Yellowstone Park this summer should not miss a visit to this handsomely housed collection.”

The opening exhibition, The Land of Buffalo Bill, included a who’s who of western American art: George Catlin, Alfred Jacob Miller, Albert Bierstadt, John Mix Stanley, Solon Borglum, Charles M. Russell, and Frederic Remington, to name a few. Most of the artwork was on loan, but McCracken worked hard over the next several years to acquire many of the pieces for the Whitney gallery’s permanent collection.

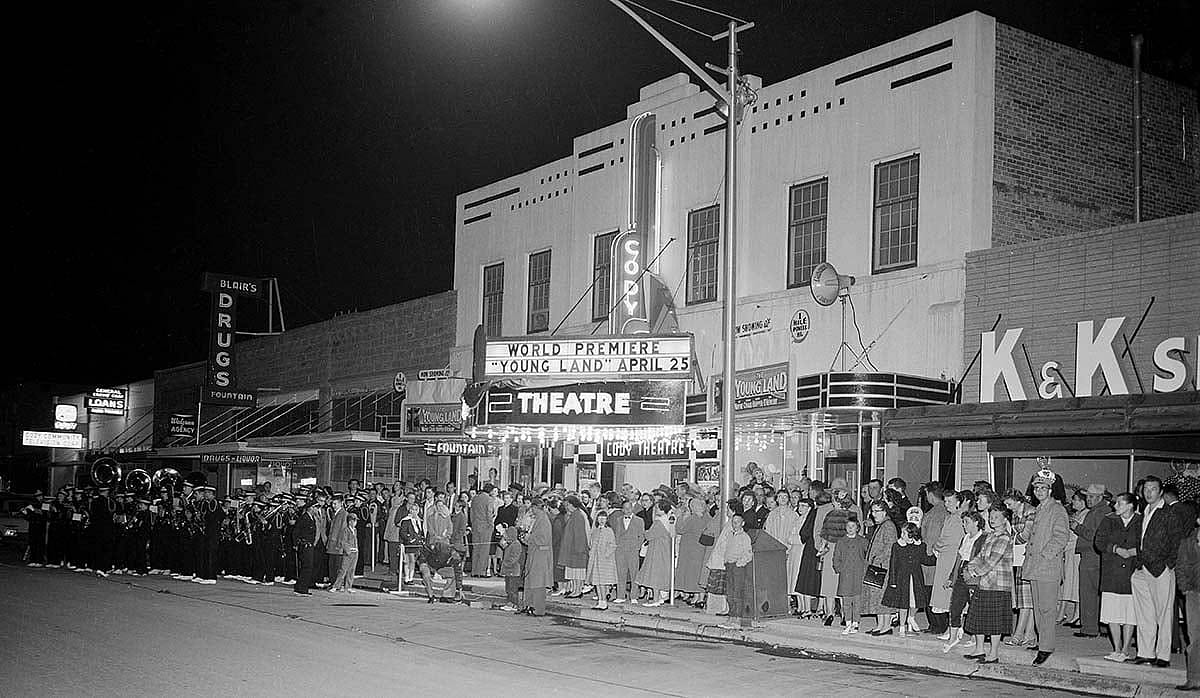

The opening festivities included more than just a preview of the new building and the opening exhibition, reportedly valued at over $3 million. The town of Cody rallied together and hosted a grand celebration to impress an estimated 1,000 out-of-town visitors. A reception and dinner at the Cody Auditorium sponsored by the Cody Club followed the dedication and formal opening of the gallery. After dinner, guests could attend a movie premier of The Young Land at the Cody Theater, starring young Patrick Wayne, son of John Wayne. Finally, the day concluded with a community get-together celebration and dance.

Major collections…

With the successful opening of the Whitney gallery and the international recognition it garnered, 1959 was a great milestone in our history, and the momentum continued. McCracken successfully expanded the collection during the early years of the Whitney gallery. More and more first-rate art came to the museum either on loan or for the permanent collection. McCracken accepted many gifts of art and purchased many others for the gallery, thanks in large part to a pair of primary donors to the Whitney gallery at the time—Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and the Coe Foundation.

The early years were also a time for building relationships. Some of the lenders to the opening exhibition became friends and supporters of the Whitney gallery for decades to follow. For example, William E.Weiss first learned of the Whitney when he loaned his newly acquired collection of Charles M. Russell’s paintings and bronze sculptures to the opening—and the Weiss family continues to lend artwork to the gallery today.

The gallery also received some very generous gifts. Pearl Newell, owner of the Irma Hotel, died in 1964 and bequeathed the Irma’s collection to the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association. Many of the objects from the Irma’s collection were from Buffalo Bill’s own art collection, such as A.D.M. Cooper’s Relics of the Past. In 1965, Harry Jackson’s large paintings, The Stampede and The Range Burial were completed and installed in the gallery, another generous donation of the Coe Foundation. These are only a few examples of the incredible patrons and collections that came to Cody in the beginning years.

Scholarship, exhibitions, and new installations…

If the early history of the gallery was notable for important collections, the next two decades were marked by exhibitions and scholarship that presented cutting-edge ideas about the West and its art. Peter Hassrick came on board as the new director in 1976 and wanted the Buffalo Bill Historical Center to be at the vanguard of changing philosophical concepts and evolving ideas about the West. Exhibitions involved the best scholars in the field and were accompanied by high quality publications.

The active exhibition and loan schedule established in the 1980s kept the historical center and the Whitney’s collection in the public eye. Exhibitions such as Rocky Mountains: A Vision for Artists in the Nineteenth Century (1983), Frederic Remington: The Masterworks (1988), and Discovered Lands, Invented Pasts: Transforming Visions of the American West (1992) were all successful traveling exhibitions. These catalogues continue to be popular reference books for American art history.

Over the past thirty years, there have also been many changes and additions to the gallery installation. Starting with the Remington objects, studio collections now forma strong base for the Whitney’s collection and a unique experience for its visitors. In 1978, the recreation of W.H.D. Koerner’s studio was dedicated thanks to Ruth Koerner Oliver and W.H.D. Koerner III, the artist’s children.

In 1981, inspired by the Koerner studio recreation, Laurance S. Rockefeller donated the funds necessary to install the reconstruction of Frederic Remington’s studio. (Previously, the collection had been shown in display cases.) In 1986, Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Fenn donated the studio cabin of Joseph Henry Sharp to the historical center, which was then relocated from Montana to Cody. Phimister Proctor “Sandy” Church donated the latest studio collection in 2006: that of his grandfather, sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor. The Proctor studio will be the newest studio installation in the Whitney gallery when it reopens this summer.

The Whitney gallery was closed in 1986 for a renovation to update lighting, wall, and floor treatments. Dr. Sarah Boehme, the first John S. Bugas Curator of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art, came to Cody in time to oversee the reinstallation and reopening of the gallery the next year. In the 1990s, as the contemporary western art collection grew, the H. Peter and Jeannette Kriendler Gallery of Contemporary Western Art was dedicated on the mezzanine level where the collection continues to be on view, thanks to Peter Kriendler and William D. Weiss.

50th Anniversary

No matter the changes and improvements in the Whitney gallery, we have always remained true to our original building. In fact, the gallery formed in 1959 would become the core structure of today’s Buffalo Bill Historical Center. Once this outstanding gallery was built, the remaining museums of the center grew up around it, each rising to the high standard set by the Whitney.

With great anticipation and excitement, we’re anxious for the grand reopening of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art this summer as we proudly reflect and celebrate the past fifty years. Our history and identity are marked by generous donors, a world-class art collection, significant scholarship and exhibitions, and new ideas. In 1959, the Los Angeles Times encouraged travelers to stop and see the Whitney gallery as they headed to Yellowstone Park. Now, fifty years later, I think you should plan a trip to the Whitney Gallery of Western Art this summer—and stop to visit Yellowstone National Park if your schedule permits.

About the author

In January 2007, Mindy Besaw began her tenure as the John S. Bugas Curator of the then-named Whitney Gallery of Western Art. With a background in contemporary art as well as art of the West, Besaw’s special interest is to connect contemporary western art with its historical counterpart. Before her arrival at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, she served as Curatorial Associate at the Institute of Western American Art in the Denver Art Museum. While in Colorado, she was also an adjunct instructor in art history at the University of Colorado–Denver. She earned her bachelor-of-fine arts degree at the University of Illinois, Champaign–Urbana, and her master’s degree in art history at the University of Denver. After overseeing the reinstallation of the Whitney gallery, Besaw pursued her doctorate degree, after which she returned to the Whitney. In 2015, she was appointed curator the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Post 245

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.