Talking Machine West 1902–1918 (part 1) – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2017

Talking Machine West 1902–1918, Part 1

By Michael A. Amundson

Mike Amundson, Northern Arizona University Professor of History, has quite the collection of Edison cylinder records and 78s, and an Edison phonograph on which to crank the tunes. Professor Amundson launched into a study of songs—from the culture surrounding them to their individual history and sheet music. Here, he shares research from his book Talking Machine West: A History and Catalogue of Tin Pan Alley’s Western Recordings, 1902–1918, published in 2017 by the University of Oklahoma Press.

Between 1902 and 1918, a cowboy-and-Indian music craze, played on hand-cranked talking machines, swept through American popular culture. Much stronger than the “trickle” of “novelties” suggested by western music historians, this furor produced more than fifty cowboy and Indian recordings. That list included cowboy poetry, western skits, cowboy tunes, love songs, Indian melodies, Wild West show ditties, cowgirl ballads, World War I Indian warrior anthems, and both cowboy and Indian ragtime dance tunes.

At the same time, music companies printed elaborately illustrated scores of almost every song, providing a sort of “cover art” in an era when discs came in simple sleeves and cylinders in tubes. Of these, sixteen such songs made it into a reconstructed Top 20 created by music historian Edward Foote Gardner (Popular Songs of the Twentieth Century: Vol. 1: Chart Detail & Encyclopedia, 1900–1949), eleven into the Top 10, and three reached No. 1—all back when Roy Rogers and Gene Autry were still in diapers. This early brand of western music used ragtime’s syncopated rhythms to portray the nostalgic passing of the Indian and the frontier; cowboys; the New Woman; and the racial attitudes of Jim Crow America. This mostly unknown soundscape flourished two decades before radio became popular and suggests another way in which the imagined West affected American culture.

Early recording industry

The music recording industry was in its earliest forms in the early 1900s. From its invention by Thomas Edison in 1877, the phonograph developed into an industry by 1900 through the work of Emile Berliner and Alexander Graham Bell. Along the way, two different media, the cylinder and the 78 disc, dominated the industry. Their musical source focused on New York’s Tin Pan Alley, where music publishing companies drew from Broadway’s many theaters and clubs, producing sheet music for parlor pianos and singers for the growing phonograph business. Publishing companies like Jerome H. Remick researched the markets to determine what style of song was popular, and then had their composers write songs in similar fashion. When complete, the company used in-house artists who drew on the latest in color lithography to produce vibrant title pages to attract attention. Moreover, they hired musicians, called “pluggers,” to perform the songs in music stores across the country and to sell them to professionals in vaudeville.

We call this popular music “ragtime”—a catchall phrase for a modern form of music with syncopation. But it also included cakewalks, two-steps, and trots. The era also produced comic songs, ethnic songs, minstrels, and the so-called “coon songs,” a racist and pejorative name for music that mocked African Americans. Ragtime, or simply rags, weren’t always the piano music we know from The Entertainer, but were often nostalgic ballads that played upon idealized images of the past to reflect on the changing condition of modern life. This nostalgia overlapped nicely with easterners’ views of the American West. An extensive recounting of this traditional western storyline is not presented here; instead, a succinct overview reminds us of the historical context that coalesced in the first decade of the twentieth century, bringing popular ideas about the West to the national audience:

- Buffalo Bill’s Wild West featured its own Cowboy Band to provide incidental music during performances.

- Turner’s “Frontier Thesis” argued that the frontier was the cutting edge of American culture.

- The birth and expansion of western tourism presented the region as an antimodern and primitivist escape.

- “Westerner” Theodore Roosevelt was president.

- The Indian “Craze” of the late 1800s and early 1900s promoted the “noble savage” and “passing Indian” tropes as popular American icons.

- There was an expanding notion of “whiteness.”

- The ensuing racial and ethnic tensions associated with the Jim Crow era increased.

- Finally, the immensely popular publication of the first “western,” Owen Wister’s The Virginian, which went through fourteen printings its first year.

While we could certainly go into the context and theory as to why such songs were popular then, I’d rather share some of these earliest recordings from my collection to give a sense of what I mean. Let me just say that these were not songs “of” or “from” the West, but eastern projections of the region and its peoples. John Lomax’s work on frontier ballads had not yet appeared, and few of the composers had been past the Mississippi. None of the sheet music illustrators had been west of the Hudson, and just a couple of the recording artists had been out West. These are, therefore, part of the “West of the Imagination,” called by some “Indianist and cowboyist” songs.

Indian love songs

Nostalgic Indian love songs suggested a simpler, more primitivist West. There, Tin Pan Alley songwriters imagined the Indian as part of a passing tableau with such music mere glances into a romanticized, idyllic past. These tunes reflected a continued romantic fascination with Native America, offering a more subtle racism through skin color references and pidgin English than the later, more overt bigotry in what I call the Jim Crow songs. Since assimilation was the assumed fate of Native Americans, several of these tunes were considered by the public as authentic representations of Native cultures. They also often conveyed messages of middle-class domesticity where Indian maidens tended house for their warrior braves.

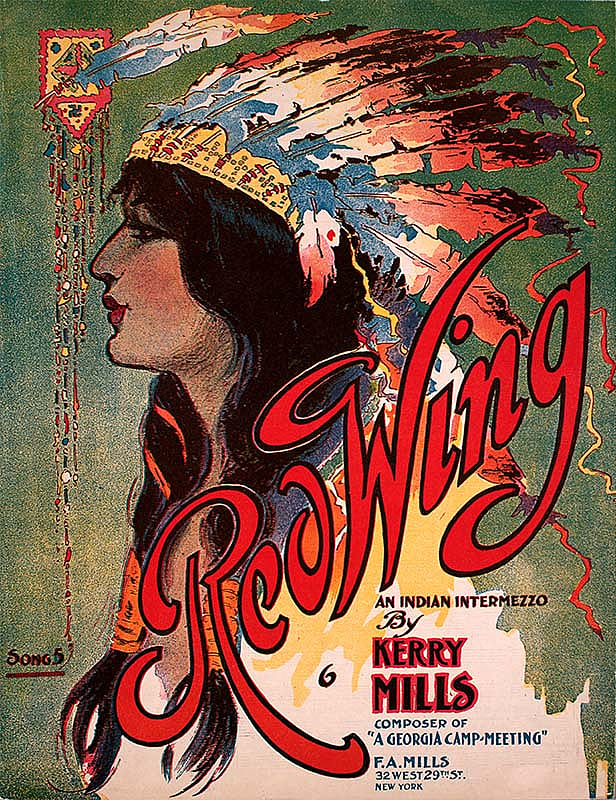

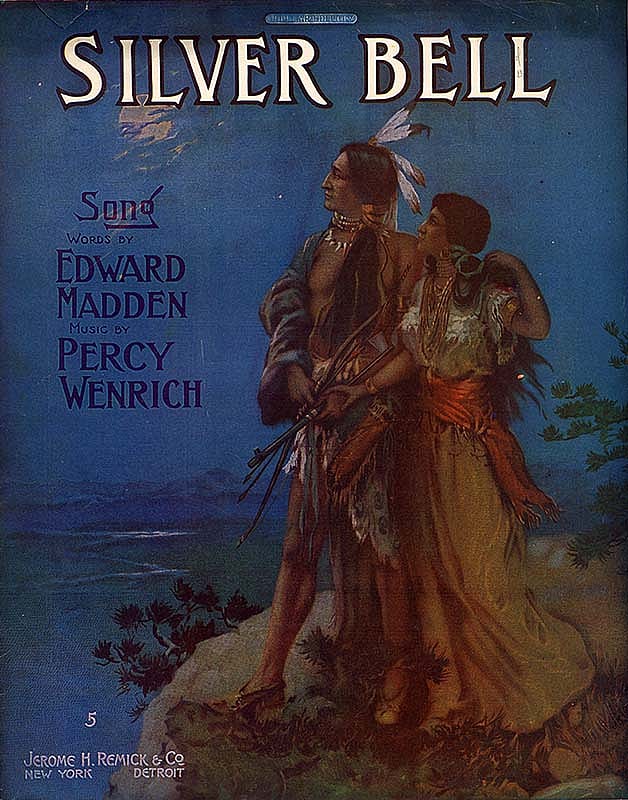

Except for Red Wing, the songs have mostly been forgotten—titles like Feather Queen, Silver Heels, Iola, Reed Bird, Topeka, Rainbow, Blue Feather, Lily of the Prairie, My Prairie Song Bird, Silver Bell, Valley Flower, Silver Star, and Golden Deer. Many were offered both as vocal songs and instrumental intermezzos. Like all records of this period, copycat songs were popular as publishers tried to capitalize on the hottest sellers.

Sheet music illustrators also flourished with some of the most beautiful cover art of the era including Reed Bird, Red Wing, and Blue Feather. These songs also found their way to some of the era’s most productive and popular recording artists, including Billy Murray, Ada Jones, Harry Tally, Harry Macdonough, Arthur Collins, and others. Indeed, from 1903 to 1913, the Indian love song remained fertile ground for the early music industry including the era’s first big hit, 1903’s Hiawatha; a 1906 follow up by the same composer called Silver Heels; and 1911’s Silver Bell.

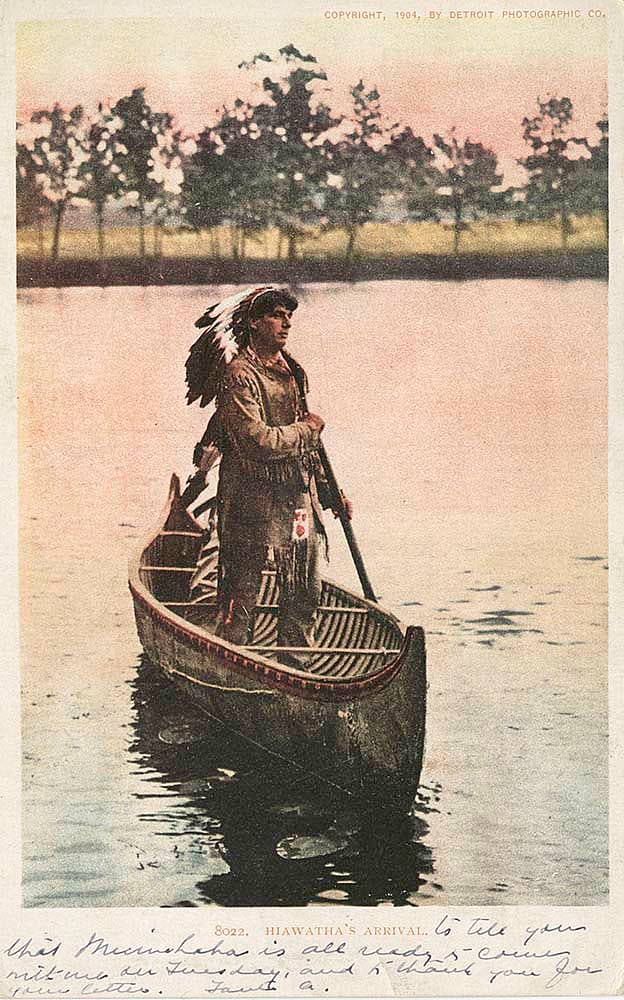

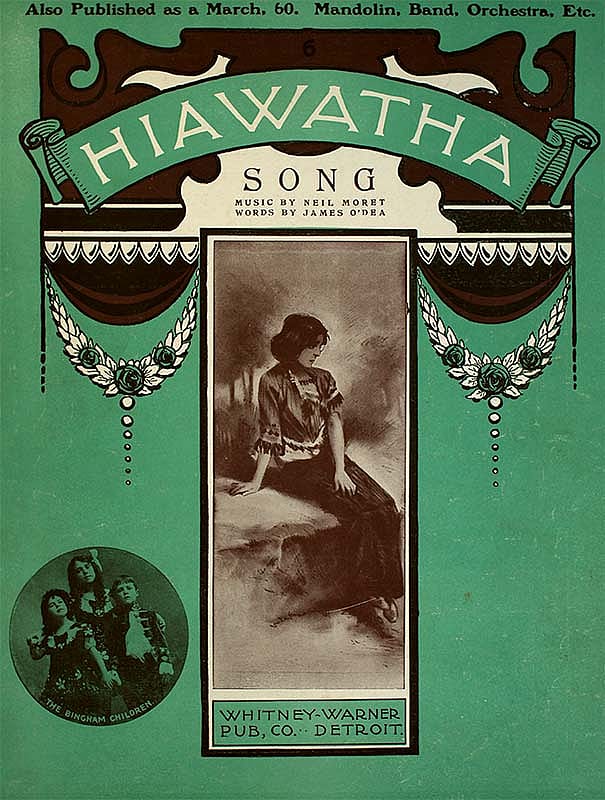

Hiawatha got its start when Charlie Daniels, a Kansas City songwriter, wrote the piece under the pseudonym Neil Moret as a love song for his sweetheart then living in the small town of Hiawatha, Kansas. After selling the tune in 1902 as In Hiawatha to the Whitney-Warner Publishing Company of Detroit for the unprecedented amount of $10,000, the composer dropped the preposition in the title, changing it simply to Hiawatha. The editing proved successful and the song sold more than a million copies of sheet music within a year. In 1903, lyricist James O’Dea added words to the tune, focusing on the popularity of Longfellow’s 1855 epic poem Hiawatha, essentially turning the original song about a Kansas town into a love song Hiawatha sang to Minehaha. This change proved popular with the American public, and more than a dozen bands and artists recorded it on multiple labels for both cylinder and disc.

I am your own, your Hiawatha brave;

my heart is yours you know.

Dear one I love you so—oh Minnehaha

gentle maid decide.

Decide and say you’ll be my Indian

Bride.

Moret and O’Dea teamed up again for Silver Heels two years later. Even more than Hiawatha, Silver Heels, with its love story between an “Indian brave” and the “sweetest and the neatest little girl,” clearly has overtones of assimilation and domesticity. During the chorus, for example, the Young Chief suggests that he will build Silver Heels “a big teepee” if she came and “cooked his meals.” Then, during the second verse, he suggests that the two of them will be “right at home” with a “hubby and chubby little papoose on her knee.” Further, its use of pidgin English in lines such as “heap much kissing” suggests a derogatory attitude toward Native Americans rather than the admiration Moret purported at the time.

Ironically, some in the period press praised Silver Heels for its authenticity. The Santa Cruz, California, Sentinel noted its composition was “founded upon the Sioux style of chant” while its “Indian aroma” was “pregnant with all the glamor of the Wigwam—the fire dance, the holocaust, and the triumphal march of conquest.” Harry Tally sings it for Victor in 1906 on my copy, while Columbia and Edison featured instrumental versions. The song hit No. 6 in February 1906. The final song of this genre, Percy Wenrich’s Silver Bell, also made appeals to domesticity and assimilation. Although the song’s lyrics contain very few references to Indian-specific Indian items, its sheet music cover was the first to show an Indian couple, rather than just a female. For the Edison recording, the popular duet of Ada Jones and Billy Murray sang the song, accompanied by orchestration and featuring a bell solo with violin between choruses. Even more interesting, Murray sang a counter melody of “Home, Sweet Home” while Jones sang the lyrics, clearly suggesting the broader theme of domesticity and assimilation. The styling proved very popular, and the Edison Phonograph Monthly suggested that the song was among “the biggest sellers we have ever cataloged” when Silver Bell reached No. 6 in January 1911.

Red Wing, by Kerry Mills, sheet music, F.A. Mills, New York, 1907. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

Silver Bell sheet music, 1910. Music by Percy Wenrich by and words by Edward Madden. Jerome H. Remick, New York. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins.

Hiawatha, sheet music, 1903. Music by Neil Moret and words by James O’Dea. Whitney-Warner, Detroit. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins.

Looking at Indian love songs collectively, some broad themes emerge including the music and internal rhyme schemes, lyrics that generalized all Native American life, the focus on assumed domestic practices and the presumption of assimilation, the generic cover art work, and the recording artists and their styles. At the same time, these songs suggest a stereotypical, racist attitude toward Native American life. With references to skin color and gender role assumptions, these so-called Indian love songs really had nothing to do with Native Americans or love, but were simply fantasy projections made by white Americans to assert their perceived dominance.

About the author

Dr. Michael Amundson teaches history of the American West at Northern Arizona University and is Public History Director for the university’s history department. He’s written several books on the history of Wyoming and the University of Oklahoma Press just published Talking Machine West: A History and Catalogue of Tin Pan Alley’s Western Recordings, 1902–1918 in 2017. He has interests in the “atomic West,” photography, the Southwest, polo in northern Wyoming, and the recent history of the West.

In the next issue of Points West, Amundson shares more “talking machine cowboys and Indians”; next time it’s “cowboys and cowgirls.”

Post 249

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.