Talking Machine West 1902–1918 (part 2) – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2017

Talking Machine West 1902–1918, Part 2

By Michael A. Amundson

In the last issue of Points West, readers learned of Mike Amundson’s unique collection of Edison cylinder records and an Edison phonograph on which to crank the tunes. The Northern Arizona University Professor of History launched into a study of songs—from the culture surrounding them to their individual history and sheet music. Below, he shares more about those talking machines—this time from cowboys and cowgirls—stories that are now part of his book from the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, Talking Machine West: A History and Catalogue of Tin Pan Alley’s Western Recordings, 1902–1918 (American Popular Music Series).

Cowboys and cowgirls

Cowboys and cowgirls were also prominent in the talking machine era. But these were not songs from the West penciled by cowpokes in the bunkhouse after a long day on the range. Instead, they were written by Tin Pan Alley writers in New York imagining the passing frontier.

Between 1905 and 1916, seventeen songs featuring cowboys and cowgirls appeared on talking machine cylinders and discs, and sheet music. Songs included Cheyenne, Idaho, San Antonio, In the Land of the Buffalo, Broncho Buster, Moonlight on the Prairie, Pride of the Prairie, My Rancho Maid, Denver Town, My Pony Boy, Ragtime Cowboy Joe, At the Wooly Bully Wild West Show, In the Golden West, and Way Out Yonder in the Golden West.

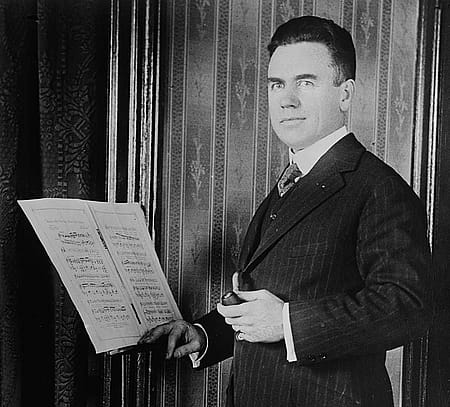

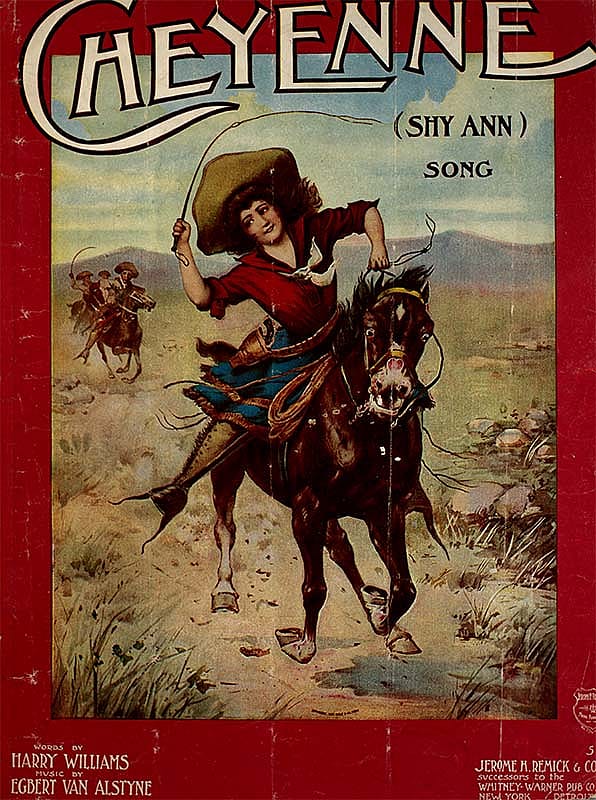

The cowboy record craze began when Billy Murray, the era’s most popular singer known for covering George M. Cohan’s songs, recorded Cheyenne in 1906. Murray had a unique tonal quality to his voice that reproduced well in the acoustic era so that his thousands of records are very clear. Murray, the so-called “Denver Nightingale,” had been raised in Denver and supposedly was “well acquainted with both Indians and Cowboys.” Harry Williams and Egbert Van Alstyne wrote Cheyenne and featured it in the two-act musical comedy “The Earl and the Girl” in 1905. The lyrics focus on a love story between a Wyoming cowboy and a cowgirl known as “Shy Ann” that read a lot like the storyline between the Virginian and Molly Stark Wood from Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian. The Victor recording featured western sound effects such as whoops, shots, wind, tom toms, and hoof beats. The recording was quite popular through the spring and summer of 1906.

San Antonio, 1907. Harry Williams & Egbert Van Alstyne. Sheet music, Jerome H. Remick & Co., New York. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. 149.073

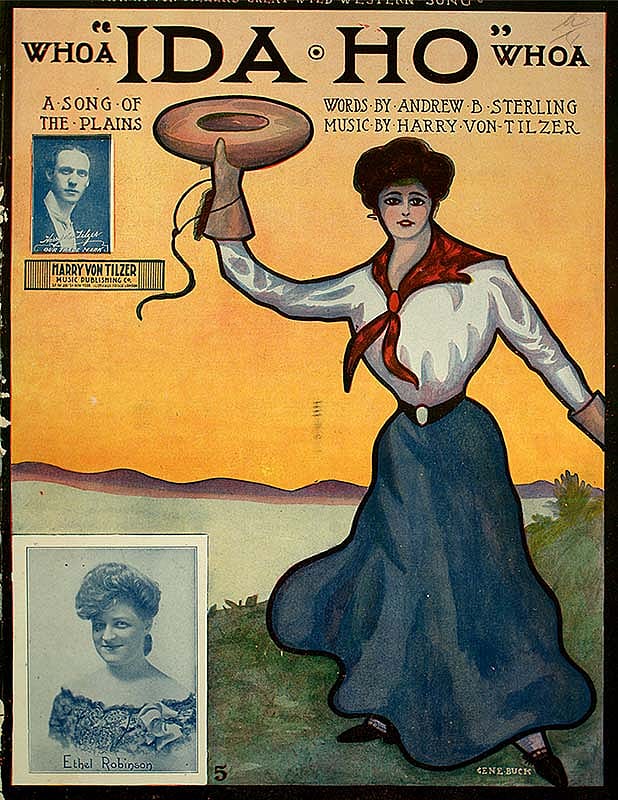

Ida-ho, 1906. Andrew B. Sterling. Music by Harry Von Tilzer. Sheet music, Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Co., New York. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. 146.193

Cheyenne (Shy-Ann), 1905. Harry Williams. Music by Egbert Van Alstyne. Sheet music, Jerome H. Remick & Co., New York. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. 145.132

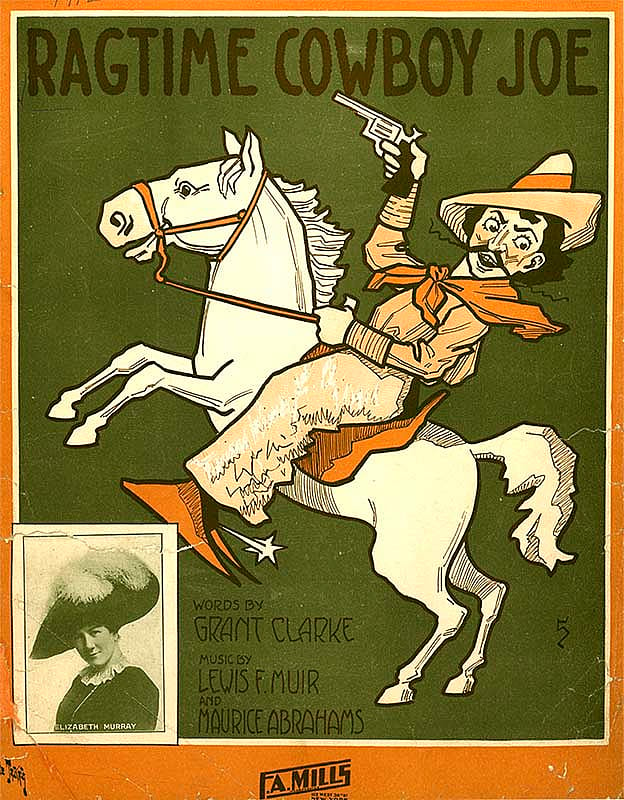

Ragtime Cowboy Joe, 1912. Grant Clarke. Music by Lewis F. Muir and Maurice Abrahams. Sheet music, F.A. Mills, New York. Wikipedia. (University of Colorado Boulder Music Library MUSICPOP 1912 Online. b33769230

Jesse James, 1911. Roger Lewis. Music by F. Henri Klackman. Sheet music, Will Rossiter, Chicago. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. 058.019

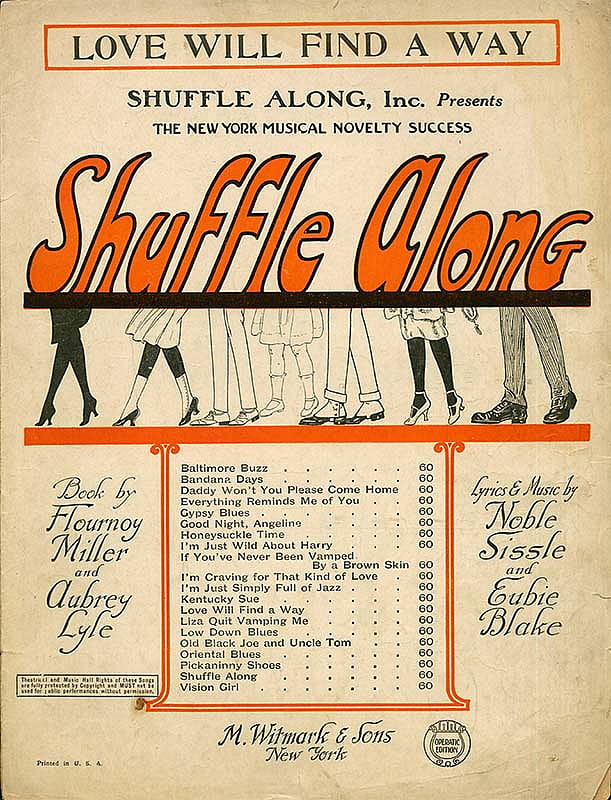

Shuffle Along, musical, 1921. Lyrics and Music by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. Sheet music, M. Witmark & Sons, New York. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. 156.070

Cheyenne‘s popularity led to another Billy Murray tune, Ida-ho, that featured a western cowgirl very much akin to the New Woman Gibson Girl image then so popular. Unlike Cheyenne, Ida-ho had no stage connection and had been written specifically for the recording industry. Nevertheless, the new song basically told the same story of a cowboy pursuing his cowgirl, once again making a pun from a western place name.

Period descriptions called Ida-ho a “breezy catchy two step typifying the true life of the Western Cowboy” and indicated that the horse’s hoof beats and cowboy yells made it realistic. Likewise, the Edison Phonograph Monthly described it as “the ‘melodious cyclone’ that is sweeping the country.” Despite these accolades, Ida-ho did not break into the Top 20.

Although other cowboy songs such as San Antonio, In the Land of the Buffalo, and Broncho Buster continued the craze, by 1911 the United States had become enmeshed in the ragtime boom, evidenced by the very popular Irving Berlin tune Alexander’s Ragtime Band that year and other hits like the Ragtime Violin and Ragging the Baby to Sleep. Perhaps the public simply was tiring of cowboy songs that longed for a nostalgic, rural frontier America where white cowboys on horses carried away their sweethearts in favor of modern ragtime, a predecessor to jazz, that was urban, influenced by African-American music, democratic, and innovative. If cowboy songs were to continue, what was needed was a song that grafted the cowboy’s popularity onto a ragtime score.

The 1912 hit song Ragtime Cowboy Joe did just this and revived the talking machine era cowboy craze by appropriating a title and words that seemed to draw from both popular genres. Technically neither ragtime nor cowboy, the song came to be associated with each music type, enjoying tremendous success as a hit song for big bands, crooners, movie stars, “The Chipmunks,” and my alma mater, the University of Wyoming, as its fight song—substituting “Wyoming” for “Arizona.”

Three Tin Pan Alley songwriters—Grant Clarke, Lewis F. Muir, and Maurice Abrahams—penned the tune in 1912 after seeing Abrahams’ four-year-old nephew Joseph all dressed up in a cowboy costume with boots and a big hat. The writers drew upon both western tropes such as Arizona, cattle and sheep herds, gun play, and dance halls while using ragtime influences to describe the “raggy music” sung to the cattle, a horse’s syncopated gait, and the “funny meter to the roar of his repeater.”

Several artists recorded Ragtime Cowboy Joe before the Great War, including “Ragtime” Bob Roberts, Edward Meeker, and baritone Ed Morton. These efforts made the song a minor hit over the fall and winter of 1912–1913. Ironically, the song became a bigger hit in England after Alf Gordon, a.k.a. “Arizona Jack,” recorded a version for the British Cinch record label in spring 1913. A newspaper reported on how the song had infiltrated London to the point that:

…so many people know the extraordinary words of some of these rag-time songs and join in the choruses. For instance, it is somewhat of a surprise to discover that prosperous and quite elderly city men can join, word-perfect in such a chorus as, “He’s the high falutin’, shootin,’ scootin,’ son of a gun from Arizona, rag-time cowboy Joe!”

A few more nostalgic songs about the West appeared before 1917, but none of them were very popular. By the time the United States entered the Great War, the cowboy music craze had ended.

About the West, from the West

The first era of talking machine cowboy and Indian songs came to an end during the Great War as popular songs shifted to patriotic ditties such as Over There. After the war, though, things changed quickly. In 1919, concert singer Bentley Ball recorded The Dying Cowboy and Jesse James, the first traditional cowboy songs that originated out West rather than in Tin Pan Alley.

Radio started the next year; Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along sparked the jazz craze in 1921; the first string bands made records in 1922; and the following year, the Glenn and Shannon Quartet recorded another traditional cowboy song, Whoopee Ti Yi Yo. Chicago’s WLS radio started broadcasting its WLS Barn Dance in 1924, and the following year, Nashville’s WSM began its Grand Ole Opry. Recording technology also improved in 1925 with the first electronic recording studios which eliminated the need for Billy Murray’s unique style of shouting into an acoustic horn. New artists such as Vernon Dalhart and Carl T. Sprague soon became famous as the first traditional cowboy artists.

Rather than the “trickle” of “novelty” Tin Pan Alley songs about cowboys and the West that music historians suggest, songs about cowboys and Indian songs were indeed present in American culture before World War I. During that time, music companies produced more than fifty cowboy and Indian recordings, and elaborate sheet music. Their presence suggests a soundscape version of the Imagined West, and when listened to closely, a nostalgia for the lost frontier and all things western.

About the author

Dr. Michael Amundson teaches history of the American West at Northern Arizona University and is Public History Director for the university’s history department. He’s written several books on the history of Wyoming, and his Talking Machine West: A History and Catalogue of Tin Pan Alley’s Western Recordings, 1902–1918 (American Popular Music Series), is now available from the University of Oklahoma Press. He has interests in the “atomic West,” photography, the Southwest, polo in northern Wyoming, and the recent history of the West.

Post 250

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.