Turning Back: Reflecting on the Art of Harry Jackson – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2014

Turning Back: Reflecting on the Art of Harry Jackson

By Mindy N. Besaw

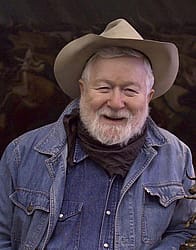

Harry Jackson (1924–2011) is a familiar name around Cody, Wyoming. He is known primarily for paintings and bronzes about the American West, but also for his larger-than-life personality. He was, in fact, the most influential and important artist to live in Cody, and local residents are understandably proud.

Two Champs (Fig. 1) is an exceptional example of Jackson’s work from this period. Cowboy and bronco are intertwined in a vortex of action, spinning out from the center, nearly weightless. Two Champs also illustrates Jackson’s innovative practice of painting his bronze sculptures in full color. Close attention to detail, dynamic composition, and polychrome surfaces are uniquely characteristic of Jackson’s work.

Without a doubt, Jackson left an impressive legacy, not just for Cody, but for today’s western American art. He can be credited as the artist who, more than any other, resurrected a dying genre of figurative art based on western subjects in the 1950s and 1960s. To categorize Jackson simply as a contemporary western American artist, however, is shortsighted. Jackson’s western bronzes were only one aspect of his astonishing career; his life experiences and varied artistic influences contributed to his overall success as an important twentieth-century American artist.

Jackson’s life—grist for his art

Jackson was born in Chicago, Illinois, but ran away from home at a young age to become a cowboy, settling at the Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming. While there, he made sketches from his saddle, and mastered the roping and riding skills of a working cowboy.

In 1942, however, he left the ranch and enlisted in the Marines. Jackson experienced intense combat in World War II, fighting in the initial assault of Tarawa and later in the assault of Saipan. He watched as his friends were torn apart by enemy artillery fire and was severely wounded himself. Jackson worked as a combat artist throughout the war, recording all aspects of military life—from the dullness of waiting to the rigors of training and the ferocities of combat. This experience required Jackson to change his drawing style from a polished technique to hasty sketches of gesture and impression to communicate conditions of extreme hardship and danger.

The war not only marked a turning point in Jackson’s career, but a shift in American Art. The United States had emerged as a powerful nation following the war, while Europe was left ravaged and poor. During the war and immediately following, many European artists fled their war-torn homes and moved to New York, establishing the United States as a cultural center around 1945. Artistically united as the “New York School,” the dominant style that emerged was called Abstract Expressionism. The style got its name from the artists’ abstract paintings, characterized by expressive paint application.

Harry Jackson, Jackson Pollock, and the New York School

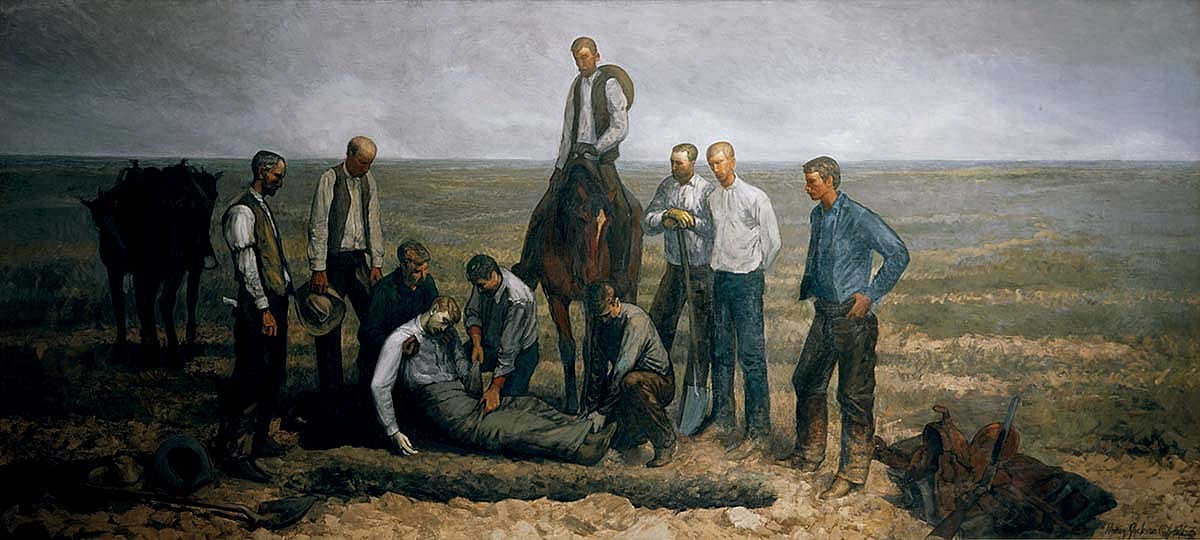

Arguably, the most important artist in the New York school was Jackson Pollock, who, incidentally, was born in Cody, Wyoming, and lived in Arizona and California as a child. Pollock’s mature style was marked by free-flowing, meandering lines of paint, layered on the canvas in a web of over-all color and shape (Fig. 2). To create his paintings, Pollock laid his canvas on the floor, and used sticks and brushes to apply the paint in calculated patterns. Jackson was particularly drawn to Pollock’s paintings, and felt that, like others in the New York School, traditional modes of representation were inadequate to express the trauma of war. Soon after the war, Jackson moved to New York to continue his artistic studies. There, he befriended Pollock, and they became such close friends that when Harry married fellow Abstract Expressionist painter, Grace Hartigan, the ceremony was held in Jackson Pollock’s living room. Patches of color intertwined with jagged lines and glimpses of complementary hues that make the larger shapes vibrate, characterize Jackson’s expressive paintings from this period (Fig. 3).

While in New York, the influential art critic Clement Greenberg almost immediately recognized Jackson as a promising second-generation painter in the Abstract Expressionist style. In 1952, Greenberg proclaimed that Jackson’s show at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York was “The best ‘first show’ since Jackson Pollock’s.” The importance of Greenberg’s support should not be underestimated. Greenberg regularly made artists instantly famous with his praise—or ruined careers with his dislike. If “Clem” was the artist’s friend, that artist easily found himself in the inner circle of artists and patrons in the competitive New York art world of the 1940s and 1950s.

Jackson returns to Wyoming…and to realism

In 1956, though, Jackson did something altogether unheard of in the art world—he turned his back on the New York School. Following a 1954 trip to Europe, he moved back to Wyoming and adopted realism for his style and the West as his subject—what Jackson called his search for the “real world.”

In a November 27, 1956, article about this transition in Jackson’s artwork, one New York Times critic called it “distressing” that a “vital young painter aligns himself with a past that can never be his.” The critic’s lament was an attitude surprisingly common at the time—not only was realism considered outmoded, but the subject of the American West was thought to be obsolete. Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, for example, were relegated to second-class illustrators and were not admired by critics or the marketplace in the 1950s.

But Jackson never abandoned Abstract Expressionism completely; rather, he took what he had learned about form, color, and composition, and applied it to the subject of the American West. Abstract Expressionism, as well as European Old Master painting and French Realism, influenced Jackson’s paintings from the late 1950s.

Trail Driver, for example, is reminiscent of Old Master full-length portraiture with a single man posed against a dark background (Fig. 3, left). His saddle, gun, boots, and cowboy hat provide clues to his profession. The rich brown of the background complements the shaded face, red shirt, vest, and leather chaps of the subject.

Jackson departed from Old Master portraiture, however, in his choice of subject. The trail driver is not a dignitary like those who would typically be featured in a portrait, and Jackson does not even identify his subject. By adopting a specific painting style, Jackson celebrated a local cowboy—his friend and rancher from Meeteetse, Cal Todd.

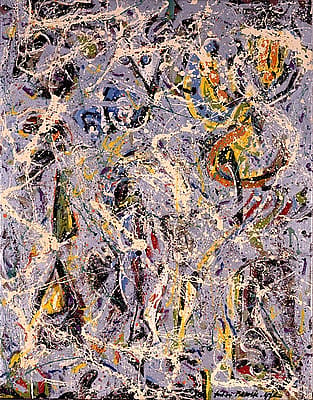

Like the nineteenth-century French Realist artists, Jackson portrayed the lives of ordinary people projected in heroic scale, as further illustrated in his two mural-size paintings, Stampede (Fig. 4) and Range Burial (Fig. 5). The paintings are not romantic and idealistic views of the past, but instead are filled with death and hardship. Stampede depicts a dark and stormy night with cattle and cowboys dashing across the surface, with one unlucky cowboy dragged by his horse into a ravine. Range Burial is the solemn scene following the death of the fallen rider.

Jackson completed the murals after visiting Paris and seeing Gustave Courbet’s 1849 A Burial at Ornans (Collection of Musée d’Orsay), which has been criticized for the way in which the artist focused on people from the small village of Ornan, burying an unknown person on a dreary day. While seemingly traditional today, French Realism was a radical departure from previous art trends, which focused on wealthy or important people overlaid with spiritual and moral messages—not the mundane activities of everyday life. In many ways, Jackson’s departure from Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s to focus on realism is just as avant-garde, experimental, and innovative.

Jackson’s later years

For the remainder of his career, Jackson continued to paint, draw, and sculpt subjects of the American West. By the late 1970s, his sculpture was nationally recognized in Art News magazine as “skillful” and “original.” Yet, the critic was hesitant, stating that his sculpture was not as relevant to mainstream contemporary art.

“The quality of Jackson’s work is outstanding,” said Janet Wilson, in the Art News article titled ‘Celebrating the American West,’ December 1978, “but the fact is that younger artists are not interested in learning what he has to offer. If you’re into scattering bread crusts on a volcano and calling it art, then Jackson’s not your man.” By this time, contemporary art had become more performance—and idea—oriented. Although Jackson’s work was unique for its roots in realism, New York-based critics rejected the sculpture as traditional and old-fashioned among the new trends.

The art world, however, is always changing. Since the 1980s, critics no longer champion one dominant school or group, and artists are recognized for working within a wide variety of media and styles, including more traditional materials like paint on canvas and bronze sculpture. Perhaps it is still too soon after Jackson’s April 25, 2011, death to find a particular place for him within the twentieth-century chronology of art. Or, more likely, his art simply resists categories—Jackson’s impact is far-reaching.

I agree with critic Gene Thornton (Harry Jackson: Forty Years of His Work, Cody, Wyo.) who wrote in 1981 that Jackson was “a figure of considerable historical importance, a pioneer…of the return to realism in painting and sculpture.” As a pioneer of realism, Jackson brought deserved attention back to the American West as a subject, not only paving the way for contemporary artists who followed, but also drawing attention to artists such as Remington and Russell.

But, Jackson is also a pioneer for leaving Wyoming to see and experience the world, to try new styles, and to always reinvent his art to express himself and incorporate what he learned. A thorough knowledge of historical styles and experimentation with Abstract Expressionism, as well as his varied life experiences, contributed to his success. If Jackson had simply spent his life in Wyoming, the state would not have such a renowned artist among her ranks.

Mindy N. Besaw is the Curator of the Whitney Western Art Museum where she spearheaded the new installation of the Whitney for its fiftieth anniversary in 2009. Prior to her arrival in Cody, she was Curatorial Associate at the Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Denver and a BFA in Art History from the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. She is currently writing her dissertation to complete a PhD in American Art History from the University of Kansas.

Post 251

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.