The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Where Do We Draw the Lines? – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2016

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Where Do We Draw the Lines?

By Charles R. Preston, PhD

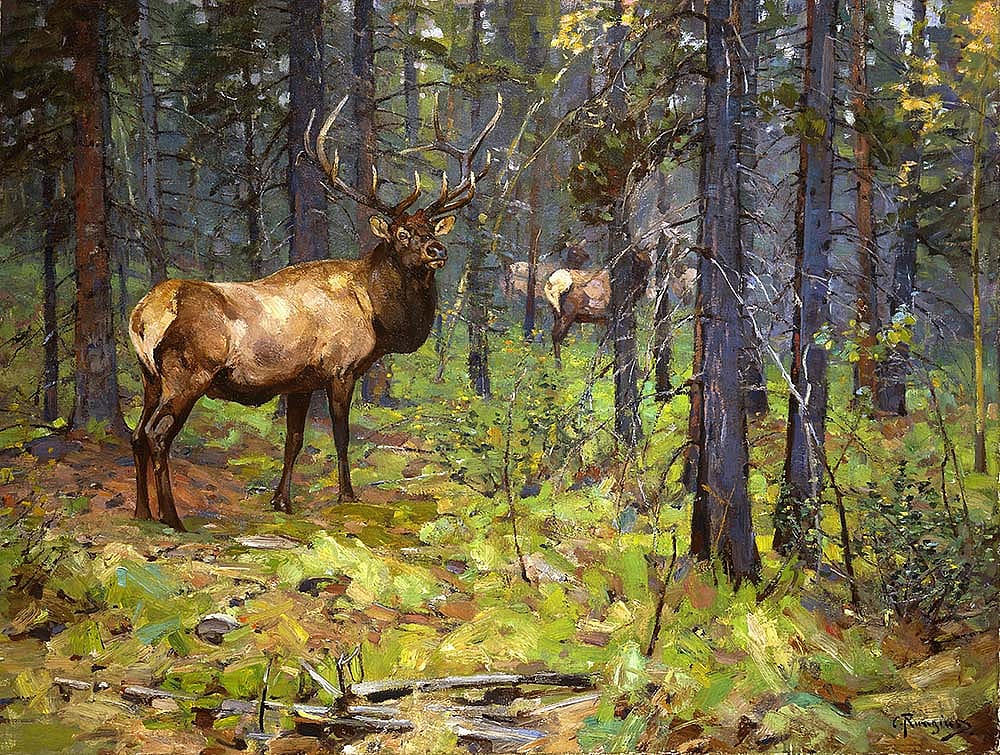

For generations, many species of animals in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, including elk (Cervus canadensis), have followed migratory paths. These trails vary little from season to season—that is, until jurisdictions and private property enter the picture with their assortment of boundaries. With a continuing focus on the relationships that bind people and nature, Curator Emeritus Dr. Charles R. Preston, Draper Natural History Museum, discusses those boundaries and the outlook for animals caught in the resultant labyrinth.

It was one of those spectacular autumn days in northwestern Wyoming, when the golden aspen (Populus tremuloides) leaves and bright, ruby, rosehip berries (Rosa woodsii) contrast so beautifully with the rich green backdrop of mixed conifers. The temperature was mild, alternately warming, and cooling slightly as the sun peaked through a broken blanket of lazy, gray clouds. Surprisingly for Wyoming, there was no wind. A few aspen leaves floated through the sky like they had no particular place to go and no deadline to meet.

Fly rod and elk-hair caddis fly in tow, I had been testing the few deep runs remaining this time of year along the north fork of the upper Shoshone River, just outside Yellowstone National Park. Despite the relatively low water, I had caught and released a couple of nice trout and was walking back along the edge of a large meadow toward my car, parked a few miles up the trail. Ever mindful of berry-binging grizzly bears in this area, I called out “h-e-e-e-y bear” every few steps and kept my eyes and ears wide open, and bear spray close at hand.

I felt vulnerable and a little incautious for setting out on this adventure in this area at this time of year without companions. But no one was available to join me; the day was too perfect; and this would be the last opportunity for me to get any significant time away from my job at the Draper Natural History Museum for several weeks. An American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) announced his discontent at my presence with a series of loud, scolding, vocal rattles, and tail flicks as I approached a bend in the trail between meadow and forest.

Suddenly, I heard the thrashing of shrubby willows dead ahead! All I could see through the thick willow branches and green-and-yellow leaves was a huge, brown, shaggy hide. The big animal was clearly in a frenzy, attacking the willow with a ferocity that even quieted the red squirrel. My immediate thought was “angry grizzly,” and my immediate action was to freeze. I was initially relieved to see that the huge body that emerged from the willows wasn’t a bear—it was an adult bull bison (Bison bison). My relief turned to something very close to panic, however, when I realized that this nearly 2,000-pound behemoth was running straight toward me!

I didn’t know how an angry bison would react to bear spray, but I steadied myself to find out. Fortunately, the big bull veered away from me just before either one of us had the chance to learn what happens when bear spray meets bison. As he crashed through an opening in the forest, I collected my thoughts and began looking around for what might have inspired the bison’s nasty mood.

I was surprised to see a small group of hikers coming down the trail from the opposite direction. They were talking and laughing softly, enjoying the sights, sounds, and smells of this place. When they saw me, they rushed my way and exclaimed with some excitement that one of the “park’s buffaloes” had gotten out of the park, and they had tried unsuccessfully to usher it back toward “where it belonged.” The group was visiting from central Utah. After explaining how lucky they were that they hadn’t been injured or worse, I asked if they knew the exact location of the park boundaries.

One of the hikers started to produce a map until I stopped him. I asked if they knew where the boundaries were without looking at the map. When they looked around at each other and shook their heads, I asked how they thought the bison would have known about the boundaries. We all had a bit of a laugh at that point, but the incident reminded me of how easily human minds grasp the concept of political boundaries, even when they are invisible on the landscape. The incident also underlined for me one of the great challenges we face in managing and conserving wildlife even in one of the world’s most renowned national parks and wildlife sanctuaries.

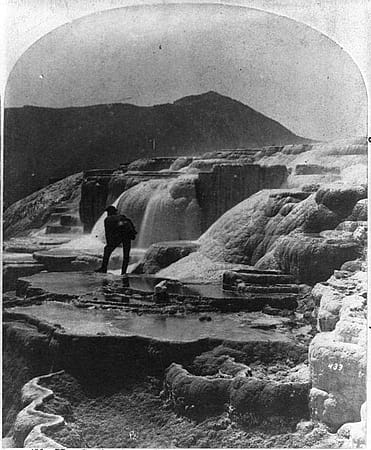

Yellowstone National Park is the world’s first and arguably most famous national park. It was established in 1872 primarily to protect several important physical attributes in the area, including Yellowstone Lake, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and especially the extensive and varied geothermal features that contain roughly half of all active geysers in the world. The park’s boundaries were drawn to address political considerations and encompass geological and scenic resources, but with little attention to biological resources. As human development expanded, however, the park’s 2.2 million acres of diverse and relatively intact native landscape became a stronghold and de facto refuge for an essentially complete complement of native wildlife species. The assemblage included bison, elk, grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), and the gray wolf (Canis lupus) that once shared a much wider swath of the northern Rocky Mountain region.

But Yellowstone National Park alone can neither contain nor sustain many of the most charismatic and wide-ranging species that inhabit the park at least part of each year. Most of the park is located at high elevation and covered with deep snow much of the year. The average elevation of the Yellowstone plateau is greater than 8,000 feet above sea level, and it’s virtually surrounded by higher mountain ranges, including some peaks of 13,000 feet. Therefore, many species must leave the park seasonally to find available resources in lower elevations.

U.S. Army General Philip H. Sheridan, a strong advocate for protection of Yellowstone National Park and its wildlife, was among the first to recognize that the boundaries defining Yellowstone National Park didn’t include adequate habitat to support viable “game” populations throughout the year. In 1882, Sheridan argued for doubling the park’s size, extending it toward the south and east to meet the requirements of migrating elk and other large ungulates (hoofed mammals). Daniel Kingman, an Army engineer and lieutenant who helped design the major roadways in Yellowstone, reinforced Sheridan’s sentiments in 1886 when he suggested that the park should expand to include both the summer and winter ranges of large game animals. Sheridan and others, including Forest and Stream editor-in-chief George Bird Grinnell and Missouri Senator George Vest, unsuccessfully fought to expand park boundaries to include additional wildlife habitat.

Eventually, these efforts to expand national park boundaries set the stage for Congress to designate much of the lands surrounding the park as timberland reserves. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison issued a proclamation that established the Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve, and in 1897, President Grover Cleveland established the Teton Forest Reserve south of Yellowstone. These reserves were the precursors of today’s national forests, administered by the U.S. Forest Service as part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The establishment of the reserves reduced opportunities for private exploitation of public lands surrounding the park. Even when such efforts expanded in subsequent years, though, the government didn’t afford some of those same protections for national park lands administered by the National Park Service under the U.S. Department of the Interior. Recognizing the need for further protection for wildlife in 1897, acting Yellowstone Superintendent Colonel S.B.M. Young advocated expanding Yellowstone Park boundaries southward to Jackson Hole specifically to help protect migrating elk. Although the park did not expand, Congress eventually did establish Grand Teton National Park in the Jackson Hole area in 1929 after many years of conflict and controversy.

Philip Sheridan, Daniel Kingman, and S.B.M. Young were pioneers in recognizing that large, unbroken tracts of appropriate habitat were critical for wide-ranging elk and other wildlife to persist in the Yellowstone-Grand Teton region. They understood that landscapes and wildlife in this broad region are profoundly interconnected, and that ungulate migration routes don’t conform to, and can’t be limited to, political boundaries.

It was nearly a century later, in the 1970s, when grizzly bear researchers John and Frank C. Craighead coined the term Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), to describe a contiguous geographic area that includes Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks and surrounding landscapes. Where Sheridan, Kingman, and Young were primarily concerned with migratory elk, the Craigheads drew the boundaries of their GYE to encompass an area of adequate size (about 5 million acres) and habitat resources that would sustain a viable Yellowstone grizzly bear population. Frank Craighead described the GYE as “…a unit that includes all the physical, chemical, and biological elements necessary for the existence and perpetuation of a complex of animal species.”

The concept of a GYE has gained wide acceptance and use, and many describe it as the last large, nearly intact ecosystem in Earth’s northern temperate zone. It has become a centerpiece for discussions and debates of ecosystem management and transboundary stewardship. Yet, there is no universally accepted size or boundary for the GYE; neither is there a specific complex of animal species to which it should be applied. Different interpretations of the area range from about 4 million acres to more than 22 million acres, depending on the subject species and the perspective of the author.

The importance of the GYE concept is that it recognizes that the destinies of wildlife and the resources on which they depend transcend political and jurisdictional boundaries. However, despite the inextricable links that bind wildlife and their resources, land managers, and other stakeholders, management of the landscapes in the various versions of the GYE is segregated among several agencies and jurisdictions with often-conflicting goals and objectives.

The GYE as most-commonly defined encompasses state lands in portions of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho; two national parks; three national wildlife refuges; portions of six national forests; lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management; tribal lands; and private lands. All told, more than twenty-eight federal, state, and local government agencies, and thousands of private landowners, manage parts of the area. Coordinated, holistic management of the area is a challenge due to the varied jurisdictions, management objectives, and philosophies found within its imprecise borders.

Recently, representatives of the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management formed the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee (GYCC) to foster communication and coordination in the management of federal lands in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks and adjacent landscapes. The establishment and work of the GYCC has enhanced opportunities for transboundary federal stewardship in the region, but obstacles remain. Now, the task for these agencies is to clearly define common goals, generate adequate resources to consistently overcome bureaucratic hurdles, and effectively pursue management objectives.

Still, even with complete agreement and synergy among federal agencies, a comprehensive vision and strategic plan for that holistic management of the entire area must also include active cooperation of state, municipal, and tribal governments, as well as private landowners. Effective wildlife management across an ecosystem, partitioned by so many human-imposed boundaries and so many diverse stakeholders, ultimately depends on identifying common objectives like socioeconomic and cultural considerations, and ecological goals.

Identifying the appropriate mix of stakeholders to cooperate in a management plan requires that the principals delineate the management area and enumerate specific management goals. Indeed, numerous authors have variously identified the 4–22 million-acre area to comprise the GYE. Subsequently, those who claim it encompasses the resources and space needed for the perpetuation of the region’s most wide-ranging wildlife believe that this provides the appropriate landscape for effective wildlife management in the Yellowstone region.

But it doesn’t.

To this point, definitions, discussions, and debates surrounding wildlife conservation and management in the GYE have focused primarily on large, wide-ranging, terrestrial mammals, including grizzly bear, gray wolf, elk, bison, other ungulates, and, to a lesser degree, Yellowstone cutthroat trout. The various published boundaries of the GYE apply reasonably well to these species, though concerns about genetic isolation and increasing habitat fragmentation have prompted some to focus more on connectivity to much broader areas, such as a Yellowstone-to-Yukon corridor for adequate grizzly bear conservation, and a western Wyoming corridor for pronghorn and mule deer. But if we consider the long-distance migrations of flying animals that inhabit Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding region during part of the year, even the most expansive boundaries usually applied to the GYE are clearly inadequate…

This article is an excerpt from Preston’s essay in Invisible Boundaries: Exploring Yellowstone’s Great Animal Migrations, a companion volume to an exhibition of the same name that was on view at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in 2016. The book is on sale in the Center’s Museum Store and also includes essays by exhibition principals Arthur Middleton, Joe Riis, James Prosek, and Karen McWhorter, with a forward by Dr. Thomas Lovejoy, Biodiversity Chair, Heinz Center for Science, Economics and the Environment, George Mason University.

About the author

Now Curator Emeritus and Senior Scientist, Dr. Charles R. Preston was the Willis McDonald IV Senior Curator of Natural Science and Founding Curator-in-Charge of the Draper Natural History Museum until his retirement at the end of 2018. Prior to that, his career path included Chairman of the Department of Zoology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science; Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock; and adjunct faculty appointments in biology and environmental science at the University of Colorado (Boulder and Denver); environmental policy and management at the University of Denver; and biological sciences at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

A zoologist and wildlife ecologist by training, Preston currently focuses on human dimensions of wildlife management and conservation in North America, especially the Greater Yellowstone region and the American West. His research interests are raptors and predator-prey dynamics, informal science education in society, and the role of scientists as public educators. A prolific writer, he has authored seven books and dozens of scholarly and popular articles on these subjects.

He continues to conduct research on the influence of climate, landscape characteristics, and human attitudes and activities on large birds of prey and other wildlife, and established a long-term monitoring program focused on golden eagles nesting in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin in 2009.

Post 254

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.