Cliff House Revealed – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2013

Cliff House Revealed

By Mack Frost

As a photographer, I constantly have to remind myself how lucky and honored I am to have the job of digitally scanning the archives of the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Every day, I get to examine historic documents and photos, and prepare them for inclusion in our online archive. Everything I work with is the authentic “Old West.” So, imagine my surprise when one of our most popular images turns out to be an elaborate fraud…sort of.

How it’s done

In the first year of my tenure as digital scanning technician, I set about the task of digitizing several long, panoramic photos from the William F. Cody collection here at the Center. These images presented something of a challenge to me, since the photos were much, much longer than the imaging area of my flatbed scanner. After a bit of research and experimentation, I developed a method of scanning the photos in sections, making sure there was at least a 20 percent overlap between each section. I then digitally “stitched” the sections together using a tool in Photoshop (the photo-processing software) called Photomerge. It works quite well, and I even adapted the method for use on documents as large as four-by-six feet.

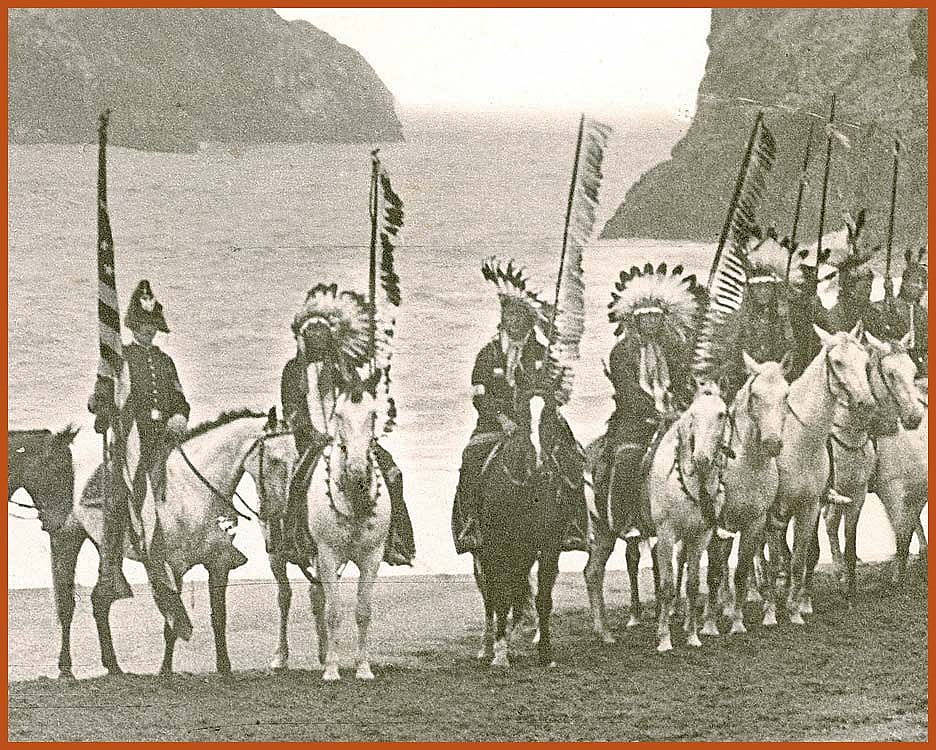

I scanned eight or so of these panoramic photos, and we placed them in the online archive fairly quickly. Two of them became very popular with collectors: One we call Two Bills, the cast photo of the combined members of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East in 1912; and Cliff House, a 1902 image with Buffalo Bill, a couple of cowboys, and more than 110 American Indians, all mounted on horses and lined up on the beach below Cliff House in San Francisco’s Sutro Heights, now known as Ocean Beach.

Picture perfect? Maybe not

Recently, a San Francisco newspaper printed a story about the Wild West’s visit in 1902 and reprinted our image of Cliff House. Soon after, I received two online orders for reproductions, one of them a request for an original size, eighty-seven-by-sixteen inches. A week or so after receiving the large print, the purchaser e-mailed me, wondering if the Cliff House photographer might have taken the photo in sections and combined them to come up with the full image. I had never considered this possibility, since all the panoramas had obviously been taken with panoramic cameras, such as the old Kodak Cirkut camera. But I did remember that while scanning Cliff House, I had noted some strange things about it, so I decided to give it a closer look.

I mentioned at the beginning that I’m a photographer. One of the styles I enjoy most is panoramic photography. I have always been fascinated with a “wide-screen” image, especially at the movies. The method I developed to scan the old panoramic photos is almost identical to techniques I use in creating my own modern panoramic images: Make sure the camera is level; take manual exposures identical to each other, and overlap the images by 20–30 percent. Photomerge does the rest. It’s a very easy way to make really wide images.

In the days of film and chemicals, however, it was not that simple. One needed a really long negative from which to print, such as one created from the aforementioned Cirkut camera; or the photographer had to make prints from sequential negatives, and cut and paste them together very exactly. Or, an individual had to make separate exposures from several different negatives, all on the same print, painstakingly aligning them (and often making mistakes), all the while protecting the previous exposures from being re-exposed by the next negative—and doing all this in the dark. Talk about your worst darkroom nightmare! It’s no wonder that I’ll take digital every time, now.

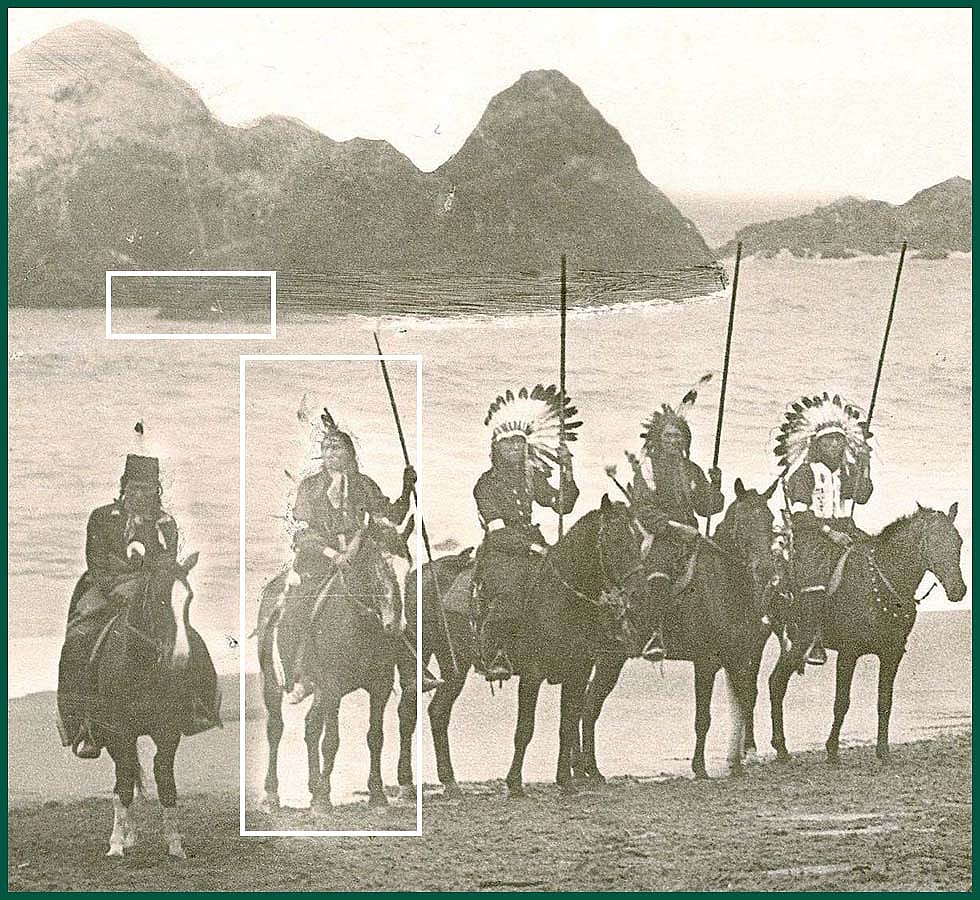

STRANGE THING NO. 1 — Figure 1

I noticed during the scanning of Cliff House that the area above the horizon of the ocean had been “dodged,” the technique of limiting the exposure of an area on a print by temporarily placing an obstacle in the light-path from the enlarger, thus reducing the amount of exposure to the chosen area only. Consequently, the blocked area appears lighter in tone than the rest of the print—the more dodging, the lighter the area becomes. The area above the sea horizon over the Indians appears to have been completely “dodged out.” I also noted four vertical shadows in the sky along the length of the photo, but I wasn’t necessarily suspicious as these appeared to be a consequence of the print aging and not part of the photographic process.

STRANGE THING NO. 2 — Figure 2

I began to check every square inch of the photo by zooming in on different segments using my computer monitor. I found that several of the Indians had tiny retouching marks around them, and similar marks appeared elsewhere such as in the sandy beach. There were also “smudge” marks in the sand near the retouched Indians. Smudging is another darkroom technique where printers rub an area of the print with their fingers while still wet in the chemistry—literally blurring the photographic emulsion of the print to hide scratches or unwanted lines, or to blend tones to make them appear uniform.

STRANGE THING NO. 3 — Figure 3

Moreover, some portions of the image did not seem to line up. There were several places where a wave on the beach behind the Indians appeared to have been cut, pasted, and misaligned—always right where the retouching marks also appeared. There was also a very glaring alignment error in the curving tracks left in the sand by a horse buggy at the left quarter of the photo.

Too many strange things happening now! This is beginning to look like a badly stitched digital photo, and I’m chagrinned to say, I never noticed it before. I’ve printed this photo dozens of times, and it never occurred to me that there might be something fishy about it. It took the fresh eye of the owner of a new reproduction to spot it for me. And then, another strange thing occurred to me: Did the Wild West ever have that many Indian performers at one time? I needed to check out those Native Americans and all the rest of the people, too.

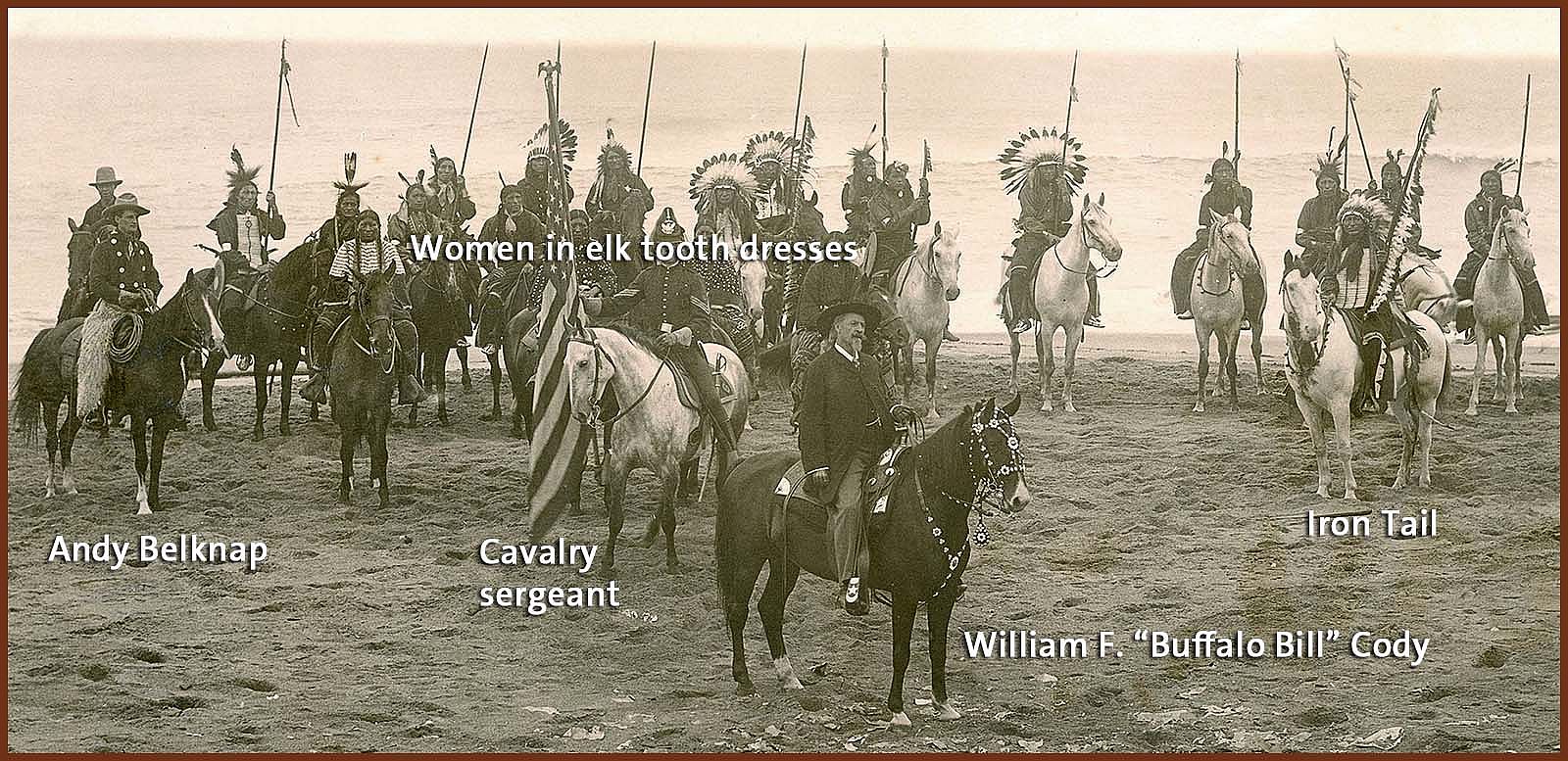

JUST HOW MANY PEOPLE ARE ON THE BEACH?

Buffalo Bill is right in the middle where you’d expect to find him, and the cavalry sergeant with the colors is right behind him. I can see Andy Belknap in the sheepskin chaps left of center in the next row of riders, and to his left are four Native American women in elk tooth dresses, and further to their left is Chief Iron Tail himself. Behind all of them is a fourth row of riders stretched out in both directions along the beach from the base of Cliff House all the way to the fishing pier. So far, so good.

Figure 4

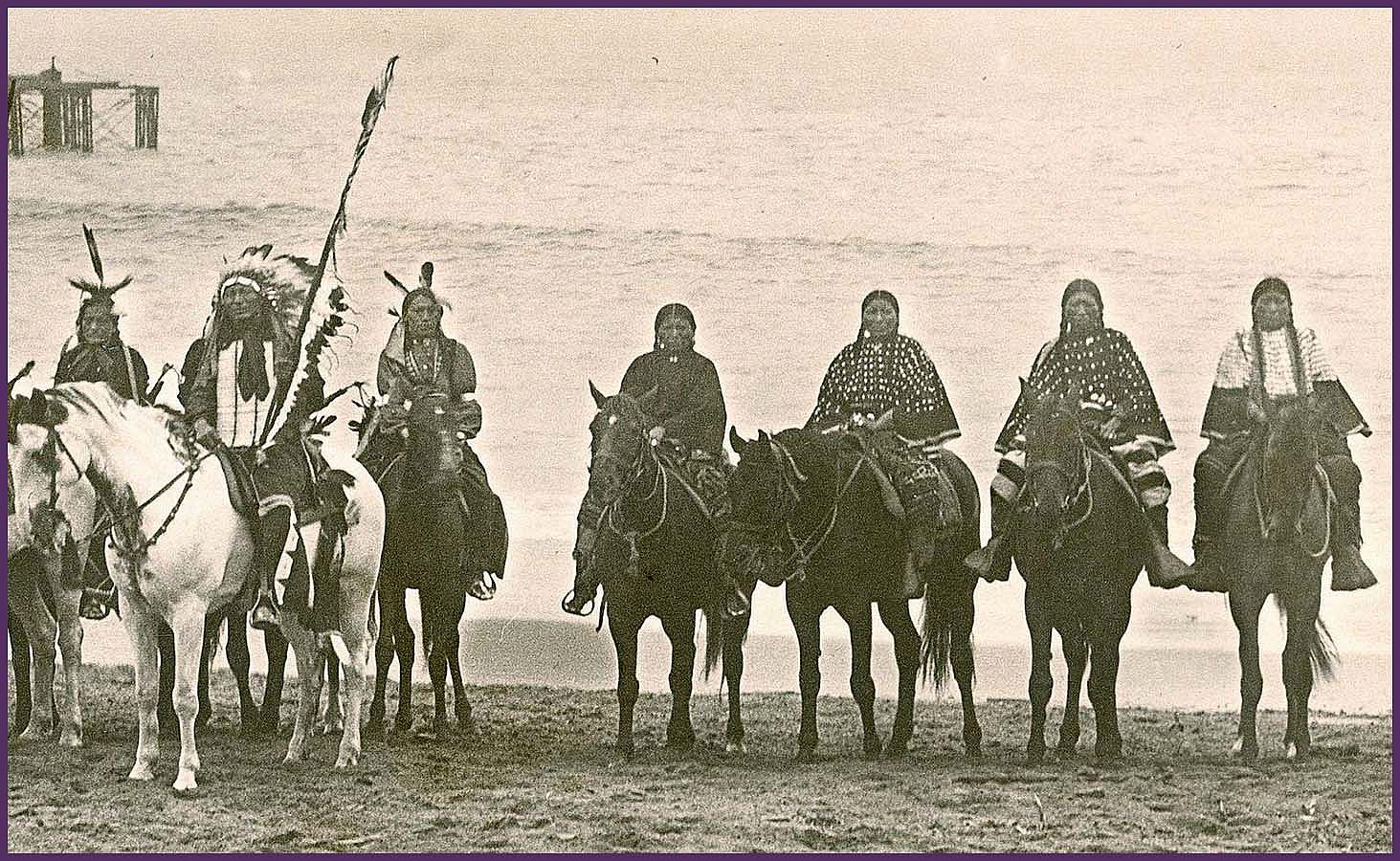

Moving left of center along the rear line of riders we see a number of men in various forms of headdress, holding similar lances. But wait! There are the four women again, but in reverse order! And next to them is Iron Tail—again! Yes: same war bonnet, same neckerchief, same bone breast-plate armor, same lance, same horse, and same saddle. This is getting interesting.

Let’s go to the right of center…yes, there’s a line of nine or ten men starting behind Bill that seem to repeat along the beach at least three times, and down there under that last island offshore from Cliff House, there’s Iron Tail again, and the color sergeant is with him!

Figure 5

Suffice it to say, I was gobsmacked, as the British would have it. There are five distinct images that make up this panoramic photo. Most of the Indians appear in the photo three times, some four times, and a few five times. I can see Iron Tail three times and his horse three-and-a-half times—it’s on a dividing line between two exposures, and one can only see the front third of the horse and Iron Tail’s lance.)

Who was the man with the camera?

I don’t know who the photographer was, and all my searching on the Internet has turned up only one other example of this photo, a cropped version from the central group of riders to Cliff House, photographer unknown. Whoever he was, he was extraordinarily clever to have directed the smaller group of Indians along this stretch of beach and “magically” multiplied them into a large company of Native American cavalry.

He captured images on an overcast day, so there were no shadows to complicate things, and that also helped in matching the exposures so that they were easier to print as one continuous image. The multiple images explain why some waves on the beach don’t line up—they were different waves. In the end, the only really glaring mistake for me is with the buggy tracks, which is likely due to the camera being moved slightly between images.

In today’s world of digital cameras and computers, such a photo as this would be incredibly easy to create. But four years before the Great Earthquake of 1906, an unknown San Francisco photographer, using a clumsy, heavy, large-format camera with a darkroom full of chemicals and photo paper—and probably a very talented darkroom worker, too—created a near masterpiece of photographic sleigh-of-hand that went unnoticed for 111 years. He would be laughing up his sleeve to know that it took this long for the rest of us to figure it out.

To paraphrase my favorite “wide-screen” villain, Darth Vader, “You don’t know the POWER of the Dark Room!”

About the author

A descendent of Park County pioneer Ned Frost, a friend of Buffalo Bill, Mack Frost was born and raised in Cody, Wyoming. He graduated from Montana State University with a degree in film and television. A noted photographer in his own right, Frost often exhibits his work in several galleries and conducts workshops on the subject. He currently serves as the Center’s digital technician, scanning a multitude of historic photographs—including those of and about his forebears.

Both the Two Bills and Cliff House photos are available from our Museum Store as well as online. We sell several reproductions every year of these panoramics, along with many other photos from our collections. I’m the one who gets to print the reproductions, too. Did I mention I love my job?!? —Mack Frost

Post 256

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.