Adornment in the West: The American Indian as Artist – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2015

Adornment in the West: The American Indian as Artist

By Donna Poulton

To the world, Millicent Rogers was a fabulously wealthy, mysteriously glamorous socialite—a visionary, a bellwether of trends who earned her immortality in the fashion firmament. On the other hand, her youngest son saw her as something far different…a collector, certainly, but also a self-appointed caretaker, a chronicler, and patron of the Native American art of the Desert Southwest.

No matter how she was viewed, though, Millicent Rogers (1902–1953) cultivated a lifelong penchant for the spotlight and had a well-earned reputation for her fashion savvy, avant-garde creations, and daring discoveries.

In 1948, the Standard Oil heiress appeared in a jaw-dropping Harper’s Bazaar magazine spread wearing jewelry she had collected from Indian artists while living in Taos, New Mexico. In doing so, she established a style that survives and thrives more than a half century after her death.

Capitalizing on the historical currency inherent in Indian jewelry—along with the connotations of an independent lifestyle and the mythic romance of the American West—Ralph Lauren, Donna Karen, and other designers followed Rogers’s lead by upscaling their fashions with Indian jewelry.

As an example, a recent issue of Vogue Italy magazine splashed the cover title, “Past, Present, Future,” across two models costumed in western, “hippie” ensembles, with Indian jewelry lining their arms and spilling from their necks. It is a cascade of silver and turquoise whose abundance echoes Rogers’s personal style and has itself become “a look.” The magazine title references a generational art form that has continuously developed for more than 150 years—from the classic or “dead pawn” period in the 1870s to the modern designs of contemporary Indian artists. It also references a preference for mixing and wearing both vintage and contemporary jewelry as a fashion statement.

While vintage jewelry has continued appeal, contemporary Indian art also attracts extraordinary interest in cities like Tokyo, Sydney, and New York. This fact is not lost on museums such as New York City’s MET (Metropolitan Museum of Art) with its past exhibition The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, or the Smithsonian with its focus on the creative genius and art of the Yazzie family in an exhibition that closed January 10, 2016, titled A Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie.

Historians of fashion and design typically trace points in time that are formed by politics, economic conditions, cultural pressures, and class distinctions. The evolution and history of the art of Indian jewelry and adornment is as complex as the lives and times of the individual artists and the tribes from which they came. No one can separate the spiritual, social, cultural, and economic meaning inherent in the jewelry they create from the objects themselves.

For thousands of years, Native groups associated articles of adornment with tribal and familial affiliations, religion, medicine, and warfare. They also used jewelry as a system of exchange. Trade with other tribes for horses—an essential commodity—as well as hides from deer, mountain lion, and buffalo was common. Moreover, individuals used jewelry as personal adornment to communicate identity. The pieces were marks of status, rank, and class, and at the same time, functioned as a way to store and carry wealth.

Pragmatically, one can divide articles of personal adornment that have captured worldwide attention into works that are perishable and non-perishable. Among the tribes in the western United States, for instance, members created artistic and exquisitely designed tobacco bags, leggings, headdresses, moccasins, shirts, dresses, and jewelry from beads, bone, quill, feathers, and hides. While highly desirable and widely collected today, these objects are fragile and require special care and conservation. Adornment and ornamentation made from silver and stone, however, have proved to be much more durable. In the context of centuries of artistic creativity, silversmithing is a relatively new art form, although it draws on a rich history and tradition of art and design.

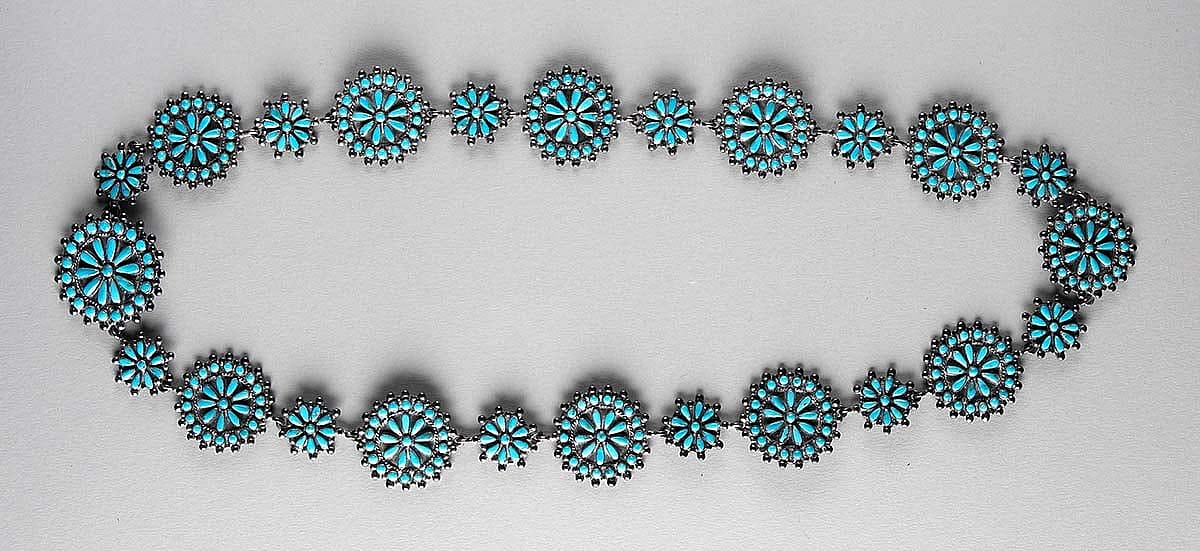

Prior to the middle of the nineteenth century, Native artists constructed jewelry with a relatively basic design from copper and brass. When artists, particularly from the Navajo, Zuni, Hopi, and Pueblo tribes in the Southwest, learned silversmithing from Mexican artisans and later from other silversmiths—often from their own families—their ideas about design quickly evolved. Foremost, they acknowledged the undeniable beauty of silver, a metal with the added benefit of being easily handled.

Silver belt buckle with 24 pieces of red branch coral, 20th century. Made by Evelyn Yazzie, Navajo silversmith. Gift of Margo Grant Walsh, in Appreciation of Ann Simpson. 1.69.6356

Note the bezel securing the turquoise stone in the center of this Navajo-style silver cast bracelet, 20th century. Gift of Margo Grant Walsh, in Appreciation of Ann Simpson. 1.69.6358

Zuni-style, inlay bolo slide with turquoise, silver, and other elements, date unknown. On loan from Deborah Hofstedt, Santa Clarita, California. L.422.2015.11

Although the Navajo knew how to forge iron to make bits, headstalls, and jewelry, some believe they didn’t learn to work with silver until just before they were brutally interred at Fort Sumner in 1864. During the four years of their detention, the Navajo had no silver to use. By 1870, however, they were making silver jewelry and experimenting with progressively more varieties of form.

In 1878, Navajo artist Atsidi Chon may have been the first silversmith to set turquoise into a silver ring with the help of a bezel, a narrow strip of serrated silver that bends to secure the stone. It took another decade before stones were used in any quantity with necklaces, bracelets, ketohs (bow guards), conchos (round, decorated disks), and other work. As access to new tools such as finer files, emery-paper, cold chisels, punches, dies, bellows, and forges became more available, the level of technical refinement and artistry increased. In his 1944 work, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, John Adair described some of the jewelry at the turn of the century as “Baroque,” meaning that it favored “testing the limits of technique over aesthetic considerations.”

It did not take long for Anglo entrepreneurs to respond to the allure of silver and stone jewelry. Anglo traders and business people quickly found ways to commercialize production and distribution, disrupting for decades to come the natural evolution of much, but not all, of the art form. Trading posts that had already increased the demand for rugs by providing weavers with wool and special dyes saw the same potential with jewelry. By giving silversmiths turquoise and silver—which they could ill afford at the time—and more up-to-date tools for their work, trading posts increased their inventory and offered a market for the artists’ work.

While trading posts exerted some influence on the course of silversmithing, it was Fred Harvey who single-handedly changed the course of silversmithing for nearly three decades. A pioneer of commercial cultural tourism in the Southwest, Harvey established restaurants and shops along the stops of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe railroads. Among the many souvenirs he sold at his hotel curio shops between 1900 and 1930 were Indian jewelry. Harvey recognized the inherent beauty of classic Navajo design, but thought it was too large, both in size and weight, and much too expensive to produce. He streamlined production and changed the design and weight of jewelry to appeal to Anglo tourists who wanted lightweight, wearable, and easily transportable souvenirs of the American West.

To incentivize sales, Harvey introduced symbols—thought to be more visually descriptive of the western experience—to silversmiths for use as stamps, even though they had little or no symbolic meaning for the artists. The thunderbird (a trademark of the AT&SF railroad), crossed and single arrows, Indian faces, and lightning bolts were among the stamps Harvey’s company introduced. And he was right: Tourists loved them; he sold thousands; and they’ve become very collectible today. Over the past sixty-five years, since the last Harvey business ended with the death of his grandson, “airport jewelry,” manufactured and imported from Asia, has filled the void. Storekeepers now sell such inventory in shops throughout the West to tourists who are not acquainted with the quality of authentic American Indian jewelry.

Another Anglo incursion into Indian silversmithing is the bolo tie. The bolo has an uncertain history, but one can find versions of the tie in a variety of countries throughout the last century, often as a means to secure a scarf or hat. Whatever the origin, it is safe to say that the bolo, as we know it today, first came into prominence and fashion in the late 1940s. Hollywood helped to promote it in western film, and Indian artists took on the challenge of creating the stunning designs worn by many today. The bolo has even found an unusual popularity among hipsters.

By the mid-1930s, government officials, disturbed by the encroachment and hybridization of Anglo taste on Indian design, feared the loss of traditional art—not only in silversmithing, but in design of pots and rugs as well. Over a five-year period, from 1935 to 1940, they took steps to curb the exploitation of Indian culture. In 1935, Congress established the Indian Arts and Crafts Board. The board’s mandate was to promote the creation and manufacture of authentic Indian works of art. Shelby J. Tisdale notes that in 1938, “[T]he Indian Arts and Crafts Board began to stamp Indian silverwork. The stamps were designed to guarantee the quality…and they served to encourage the creation of a better class of silverwork that follows traditional Navajo and Pueblo designs.”

The board’s actions paved the way for artists to become more independent by the early 1950s. Then, by the 1970s, individual artists, both traditional and more progressive, like Charles Loloma, were becoming known for their work. Today, contemporary artists such as Cody Sanderson, the Yazzie family, and others, have become superstars. They create distinctive jewelry garnering both popular and critical international acclaim, and they are keeping the art of silversmithing alive.

Collector and silver connoisseur, Margo Grant Walsh, of the Pembina Band, Turtle Mountain Tribe, Chippewa Nation explains, “I am drawn to American twentieth-century silver—both for its beauty and for the heritage it represents. American Indian silver appeals strongly to me because of how it links two traditions. As artisans, American Indian silversmiths are perhaps the single largest group in America who still maintain the European tradition of family apprenticeships, small shops, technical refinement, and innovation. And, through their artistry, American Indian silversmiths honor their own familial ties, tribal customs, and culture.”

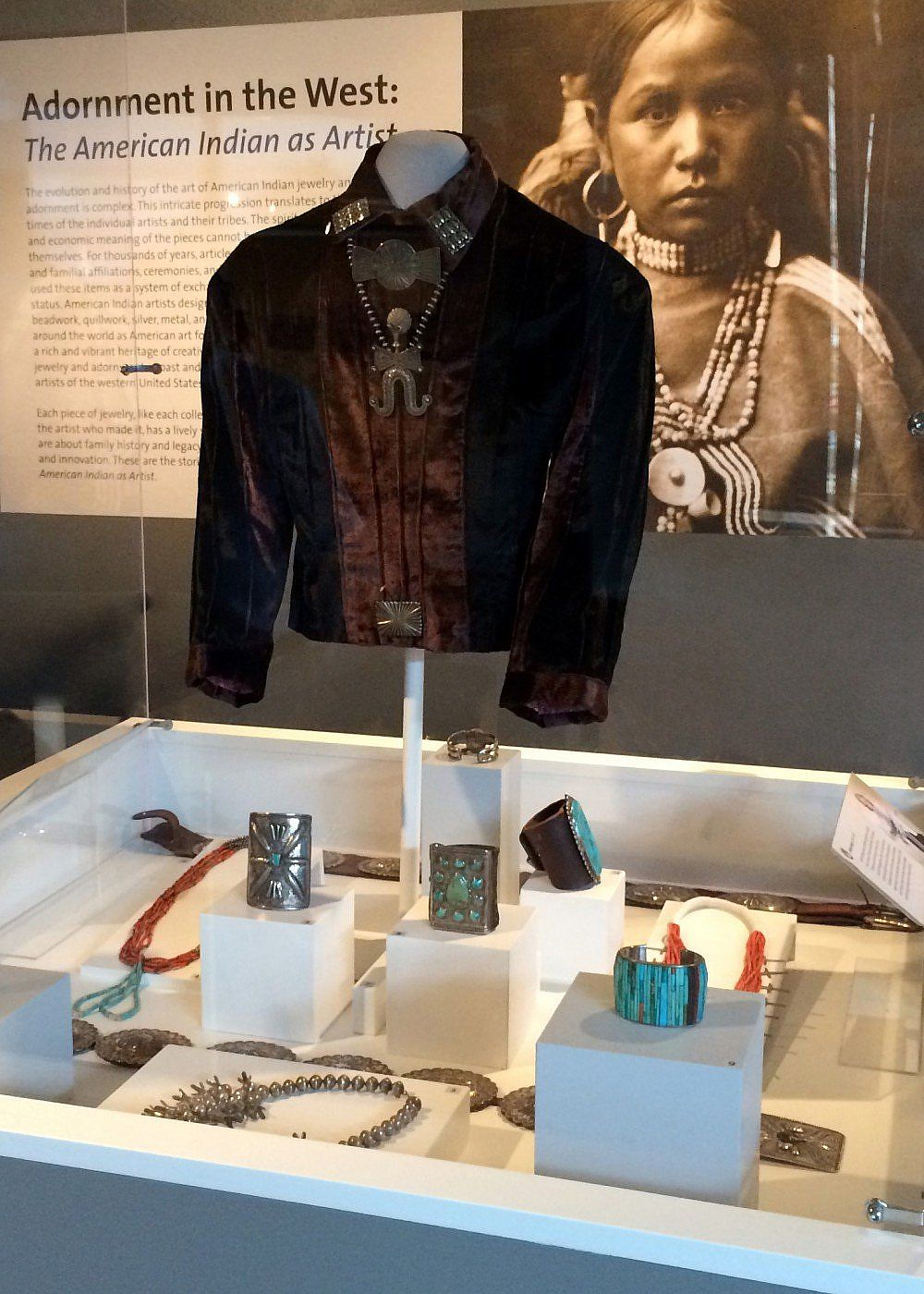

The past exhibition Adornment in the West: The American Indian as Artist, which was on exhibit at the Center in 2015, presented fine Indian jewelry made of silver, stone, bead, and bone from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Plains Indian Museum collection along with loans from the Millicent Rogers Museum. Members of the Cody community, including trustees, staff, advisory board members, friends of the museum, Patrons Ball attendees, and unsuspecting visitors taken off guard by our requests, graciously loaned work to the exhibition. The extraordinary display lauded former Center of the West directors Harold McCracken (1894–1983) and Margaret “Peg” Shaw Coe (1917–2006), visionaries who, in the early years of the museum, brought their own style and genius to the Center of the West. The exhibition included pieces from each of their collections along with so many others.

Each piece of jewelry, like each collector who loaned to this exhibition and each artist who created the work, had a lively story to tell. Some were love stories; a few were about family history and legacy; and still others were all about the appreciation of artistry for wearing and collecting. These were the stories told with Adornment in the West: the American Indian as Artist at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

About the author

Donna L. Poulton is the former Curator of Utah and Western Art at the University of Utah’s Museum of Fine Arts. She grew up in Dillon, Montana, and lived in Germany for twelve years where she studied at the Boston University extension in Stuttgart and later received her PhD from Brigham Young University. She has taught art history at the University of Utah, and juried and curated many exhibitions, including the Olympic Exhibition of Utah Art. A prolific author and lecturer, Poulton’s most recent book, co-authored with James L. Poulton, is Painters of Grand Teton National Park. She is the project manager and director of the Hal R. and Naoma Tate Foundation.

Post 258

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.