The Tipi Blends Function and Elegance – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2016

The Tipi Blends Function and Elegance

By Gene Ball

From the Archives: Gene Ball, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s former education coordinator, penned this article in 1979. Note that the three words—tipi, tepee, and teepee—are virtually interchangeable; here at the Center of the West, we use “tipi.”

Early historical records indicate that various nomadic peoples in Siberia, Lapland, Labrador, and other near-Arctic areas used conical-shaped, animal skin tents as dwellings. However, this distinctive type of transportable shelter reached its zenith among the nomadic, buffalo-hunting peoples of the American Plains.

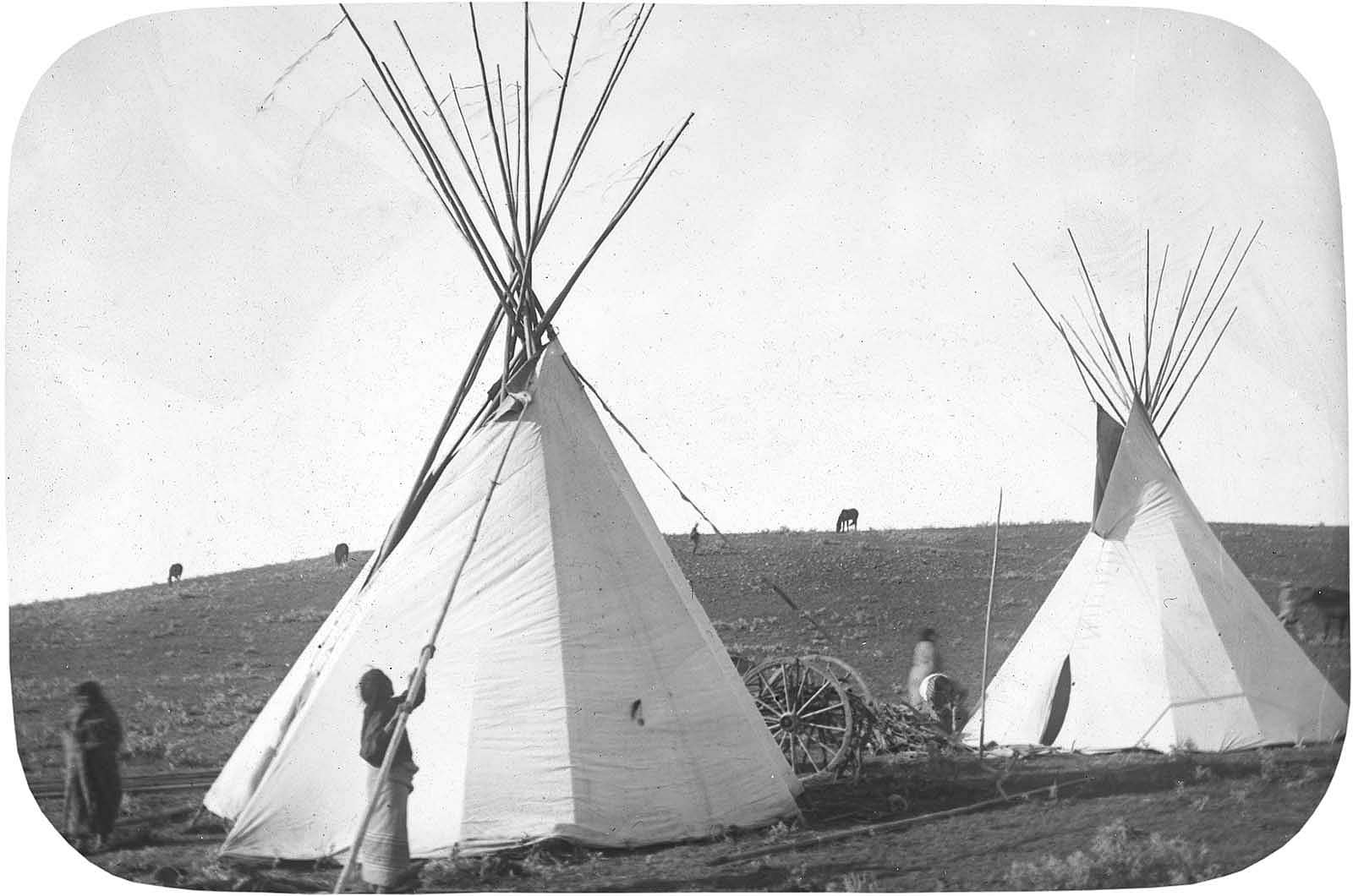

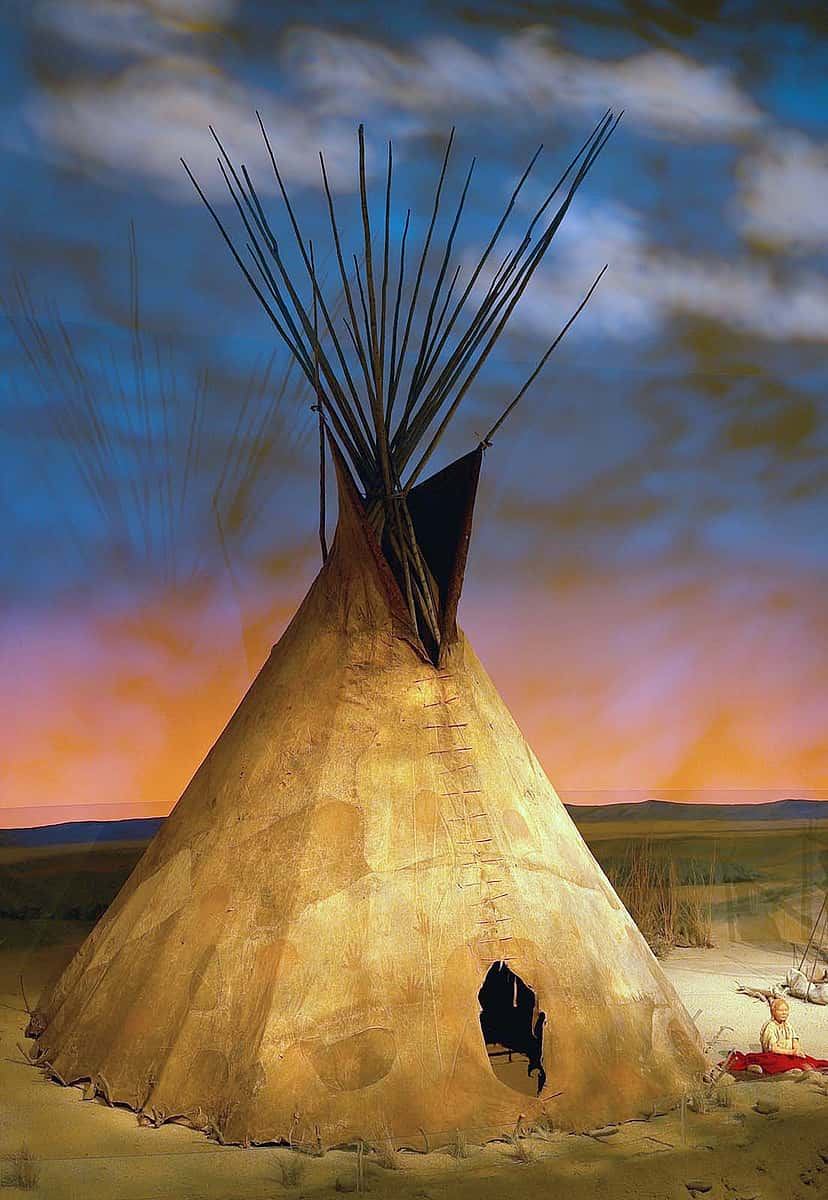

The tipi exemplifies the Indians’ aptitude for blending serviceability with elegance. It is more functional and sophisticated than other dismountable frame structures with membrane covers. This is largely due to the special flaps at the top front to regulate the draft and ventilation and carry off smoke.

Anyone who has been inside a tipi knows that it is more than a tent. As Stanley Vest has written, “…other tents are made to sell. The tipi was made to live in.”

For its occupants, the tipi has spacious standing room; raising the side cools the dwelling in warm weather; and its inverted conical shape allows for efficient heating. The shape also makes it very sturdy, able to withstand wind and rain, and even provide shelter against the tornadoes common on the Southern Plains.

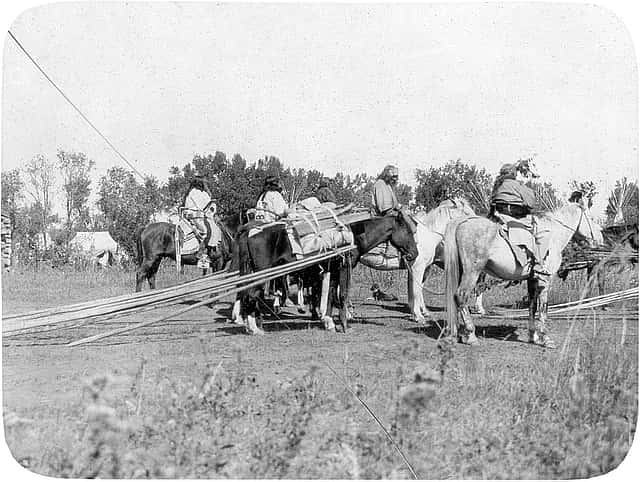

Tipi is a Sioux word meaning “used to live in.” The Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa were among the tribes who used a three-pole foundation for erecting the framework. Tribes such as the Blackfeet, Crow, Shoshoni, and Comanche used a four-pole system. Typically, poles were twenty to thirty feet long, and each tipi required fifteen to twenty-five poles. Those erecting the tipis generally preferred the straight, slender lodge pole pine, but the light red cedar was another favorite. Tipi poles also served as frames for the travois on which the Indians transported their belongings.

The tipi was the woman’s property and responsibility. In the spring, the men killed bison cows whose hides the women tanned expertly. Sewing eight to twelve odd-shaped skins together to fashion the semi-circular tipi covering was complicated piecework which required astute planning. Designing and cutting the smoke flaps also necessitated great skill.

Joint effort was the common practice, both in making and moving the tipis. When erected, their doorways normally faced east toward the morning sun and away from prevailing winds. Northern tribes used round entries, but southern tribes preferred an inverted v-shaped doorway. Moreover, the tipi was not symmetrical. The cone-shaped structure tilted slightly so that it was longer in front and steeper in back. Smoke holes extended down the front and had adjustable, ear-like flaps on each side.

The tipi was easy to transport, quick to erect or dismantle, durable, and light—all advantages to a people on the move. By the 1880s, Native peoples substituted canvas for buffalo hides, which were no longer available. For the Indians, the canvas was a practical, technical improvement. It was lighter and easier to tailor for a better fit.

Interestingly, tipi covers fashioned from animal skins seldom lasted more than two years. As a consequence, few original skin coverings exist today.

Post 259

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.