Launching the Plains Indian Museum – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2017

Launching the Plains Indian Museum

By Peter H. Hassrick, PhD

One of the key milestones in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s hundred-year history is the addition of the Plains Indian Museum in 1979. As director at the time, Dr. Peter H. Hassrick has a unique perspective on how the creation of the “PIM” is an important chapter in the Center’s Centennial story.

When the first Buffalo Bill Museum opened in Cody, Wyoming, in 1927, one of the most popular portions of the permanent display was a group of Northern Plains Indian artifacts assembled through many years by William F. Cody and his niece Mary Jester Allen. Those objects, such as the dramatic Shoshone hide painting of a buffalo hunt and Sun Dance by Cadzi-Codsiogo [Fig. 1], served as a core collection that would grow exponentially through the decades. Buffalo Bill, despite his penchant for flamboyant showmanship and presenting the “conquest” of the West as a divinely sanctioned Anglo construct, was inordinately sensitive to Native people and their cultural legacy. Collecting and preserving objects from the indigenous populations of the Northern Plains were an important part of his rather enlightened philosophical passion to use historical objects as teaching tools for future generations.

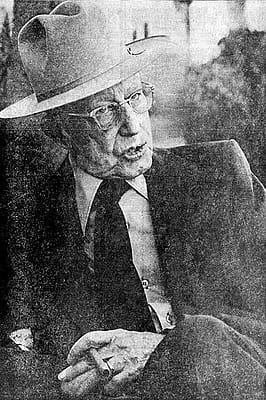

In 1969, a new Buffalo Bill Museum joined the Whitney Gallery of Western Art to become the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. The museum’s director, Harold McCracken [Fig. 2], was a nationally recognized scholar on American western art who harbored an extraordinary, auxiliary appetite for Indian material culture. He made certain in the new building that there was just as much space allocated for the growing Indian collections as there was for history and art.

Thus, in 1969, the first iteration of the Plains Indian Museum was born. It encompassed 16,000 square feet and was filled with brass and glass cases containing some 1,400 treasures, both historic and aesthetic, utilitarian and spiritual. Major donors like founding trustee Larry Larom, Cody artist Adolph Spohr, and Dr. Robert L. Anderson had donated their vast collections to the museum to be included in the displays. The Plains Indian Museum offered a veritable trove of wonders [Fig. 3].

An idea takes hold

Yet despite its ambitious scale, ambient charm, and precious store of objects, the Plains Indian Museum of 1969 had one sizable drawback—its location was in the basement. So, almost immediately, museum officials began to consider an enhanced facility. As early as 1972, a report in the Rocky Mountain News referred to it as being only “temporarily housed in the lower level of the building.”

By 1975, the museum’s trustees had formally embarked on plans for a larger and more visible home. Trustee James E. Nielson headed the fundraising program for this new enterprise, a building that was projected to cost $3.8 million and span 46,000 square feet. As he so clearly stated, “At a time when attention is being focused on the role and contribution of the American Indian in our history and society today,” he wrote, “it is appropriate to devote the time and energy of the Historical Center toward the preservation and proper display of the history of these great people.”

The museum retained a renowned Wyoming architect, Adrian Malone of Sheridan, and by early 1976, with the assistance of trustee Peter Kriendler and board chair Peg Coe, the museum obtained a challenge grant of $1 million from Readers Digest owners and founders, DeWitt and Lila Wallace. When Mr. Wallace learned over lunch one day that the Coe family had already committed $500,000 toward the project, he turned to Mrs. Wallace and asked if she thought she could match Mrs. Coe’s gift. Mrs. Wallace responded enthusiastically in the affirmative whereupon Mr. Wallace promptly matched his wife’s pledge. The drive was well underway after one productive midday meal. The Wallaces had visited the Center some years earlier and referred to the existing Plains Indian exhibits as “an outstanding memorial to the original inhabitants of the West.” It seems that they were already primed to become a major force behind the new project.

The early 1970s, when plans were being launched for this larger and more engaging museum about Plains Indians, was a period of great turmoil in the West. The American Indian Movement (AIM) was in its ascendency, and the staff of the Center felt threatened that the facility and its collections might be in real danger. McCracken had the National Guard on call just in case.

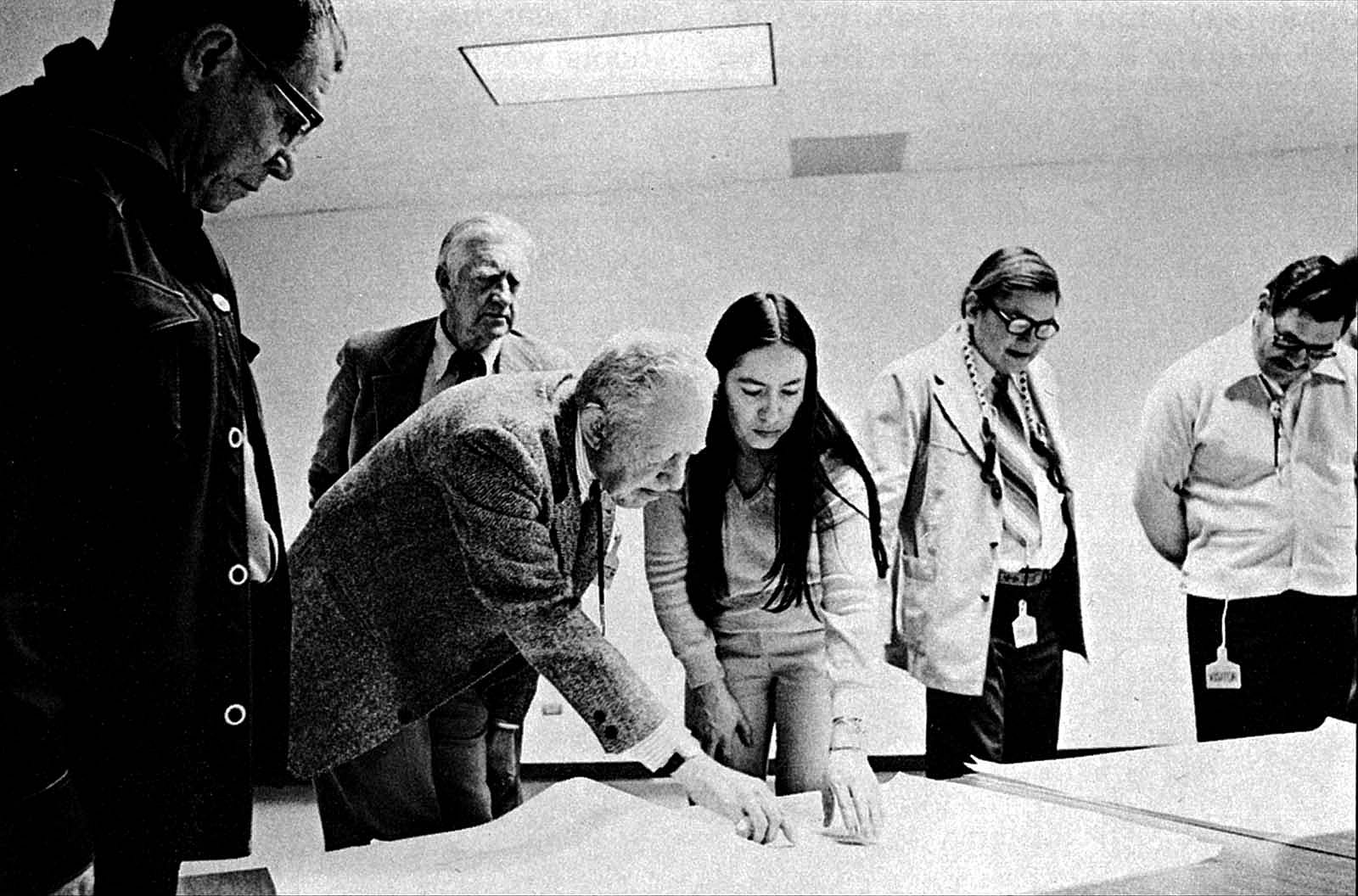

I arrived as director in early 1976, just in time to share that lunch with the Wallaces. I also wanted to head in a rather different direction in terms of the institution’s relationship with the Native community. At my urging, the board approved and appointed a Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board, the first such group in any American museum to that date [Fig. 4]. We called upon a select group of individuals from surrounding Northern Plains tribes to, as volunteers, represent their people and play a role in shaping the new museum and its program. We strove first and foremost to establish a collegial rather than adversarial association. We wanted it to be their museum as well as ours, and we needed their input into its design, mission, and conceptual construct. Their counsel was both profound and invaluable, and their presence as representatives of the northern tribes helped diffuse the tensions that had built up over several years.

The first meeting of the Advisory Board occurred in early November 1976. The group reviewed architectural plans and offered ideas on how best to interpret the collections. Two exhibit perspectives were current at the time—one that would consider the objects primarily as aesthetic pieces, and the other that focused on using the material to reveal ethnographic utility. The former approach was considered preferable even though the group wanted to leave the door open to present a few ethnological exhibits. Unanimous agreement came from all advisory board members that the museum should not display Indian remains. A favorite display for visitors had been a mummified body exhumed from a cave near Cody. The body was soon removed and laid to rest in secure storage.

Gros Ventres member of the advisory board George Horse Capture put forward one other idea. Horse Capture, who later became curator of the new museum, suggested that the institution should host an annual Indian arts seminar. It was a program, truly national and international in scope, that was up and running by the next fall, and one that endured for more than two decades.

In the mid-1970s, the Center had the promise of a remarkable collection of Northern Plains artifacts that would complement its existing holdings. This was a rich store of materials collected by the Arizona artist and long-time McCracken associate Paul Dyck. Unfortunately, at the time, the Dyck collection came with a number of conditions that were unsatisfactory to the administration and the board, and after months of negotiations, the deal fell through. Cody would not see the objects again until 2007 when the Center arranged for a partial purchase and donation from Dyck’s descendants.

Opening day

Construction on the new building began in fall 1977. Without the Dyck collection, the Center embarked on a search for material that could complement and supplement the existing Plains Indian Museum holdings. The museum identified a Michigan collector, Richard Pohrt, and the board-initiated discussions to acquire substantial parts of his collection for that purpose. A Southern Arapahoe Ghost Dance dress [Fig. 5] is exemplary of the quality and cultural significance of many of Pohrt’s assets. At the time, the museum added large numbers of equally important items from Pohrt to the collections.

To help with the initial installation, the museum assembled a team of experts composed of Richard Pohrt; Myles Libhart of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board of the Department of the Interior; Royal Hassrick, retired senior ethnologist from the Denver Art Museum; and Leo Platteter from the Center’s staff. Working closely with the consultants and the advisory board members, the staff drafted a plan, and the exhibit took shape. The new Plains Indian Museum, then in possession of about 3,500 objects, opened in June 1979 with some 4,000 people in attendance.

Author and cultural savant James Michener served as the keynote speaker, and his comments encompassed the feelings of the day [Fig. 6]. “What kind of museum should we have here?” he asked. Applauding what had already been done with the advisory board, he provided an answer: that it must be one “organized along new lines.” Here was an institution that had already, to his delight, enlisted “the support, guidance, and cooperation of Indians who know what the things in its galleries are, Indians who know what they signify, what their meanings are, and their values.” The new museum would, in Michener’s estimation, “give a lift of spirits” to its many visitors—Indians and non-Indians alike.

Behind Michener as he spoke stood the reborn Plains Indian Museum, a new 43,000-square foot addition. It was a facility that the Indians of the region could boast would preserve and present in splendid and sensitive fashion their cultural legacy. The city of Cody now featured an illustrious monument to its Native neighbors, one that commanded national attention for its collaborative conceptualization, scale of execution, and quality of ethnographic

gems.

Moving forward

Curator Horse Capture served the Center for eleven years and contributed a great deal to the success of the department. During his tenure, the museum began sponsoring an annual powwow (which still enthralls visitors and engages regional Native dancers to this day); hosted an annual, international Indian art seminar (which continued through 2007); and organized two nationally significant exhibitions, Wounded Knee: Lest We Forget co-curated with the renowned Indian historian Alvin Josephy in 1990, and Art of the American Indian Frontier with the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1992 that traveled to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Horse Capture’s ability to constructively interface with Native communities regarding sensitive treatment of sacred objects and the repatriation of tribal treasures proved to be groundbreaking and exemplary models.

When Horse Capture moved on to the Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution in the early 1990s, his replacement, Emma Hansen (an Oklahoma Pawnee), grasped the torch and carried forward in a most remarkable way. Hansen was truly visionary. She sustained many of the earlier programs, but insightfully added to them, for example, with plans to completely redesign and reinterpret the collections on public display. Following the guidance of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board and its chairperson, Harriet Spencer, the staff soon developed a fresh concept for the exhibits.

To contradict the public’s “familiar and often erroneous stereotypes of American Indians,” the new display would strive to educate people about “the essential beliefs and values that guide Plains Indian life.” Using the full array of objects previously collected, Hansen moved to reinterpret the museum’s riches to provide, in the words of advisory board member Joe Medicine Crow, a “living, breathing place” that considered Plains Indian social functions, their history, and their relationship with the environment. As Hansen wrote in her collections catalogue, Memory and Vision, in 2007, “Beyond their exceptional artistic excellence,” the museum’s objects represent “powerful expressions of their cultures, values, historical experiences, and contemporary lives of the people who created them.” The newly installed 25,000 square feet of new display space was debuted to the public in June 2000 [Fig. 7].

Hansen organized many significant exhibitions, including seminal displays on the Ute and Northern Arapahoe Indians. Probably the most complex venture she undertook was leading a curatorial team from ten collegial institutions, a consortium known as Museums West. The 1998 exhibition, Powerful Images: Portrayals of Native America, combined select items from the cooperating institutions. It addressed the notion of how outside societies have shaped public interpretations of Native life. Anglo perspectives appeared to be relatively monolithic and entrenched, while the voices from within the many Native communities were varied and quite complex. The show hoped to encourage a public audience to examine and challenge its perceptions of Native people—how those perceptions are formed, what their origins are, and how to consider them in a real world.

Today’s Plains Indian Museum

Before Hansen retired in 2014, she embarked on a major traveling exhibition and publishing project focused on the Paul Dyck collection [Fig. 8]. Titled Legacies: Indian Art from the Paul Dyck Collection, the University of Oklahoma Press published the book in 2018. It features an introduction by one of the veteran advisory board members, Arthur Amiotte.

Hansen’s Assistant Curator Rebecca West succeeded her. Also enthralled by the Northern Plains Indians, West has been a major contributor of articles, presentations, and publications. Her special interest is contemporary Indian art where she endeavors to relate today’s Indian cultures with broad social relevance to American and international audiences. The Plains Indian Museum’s annual Powwow has continued to flourish primarily due to West’s devoted attentions over the past decade.

The Plains Indian Museum celebrates the cultural past and the living present in equal measure. Its mission is summarized in the axiom that “the past is best used when it serves the present and the future.” It has come to be a museum not just about Native people of the western prairies and mountains, but an institution of, for, and by Indians of the region. As such, it provides all audiences an extraordinary opportunity to learn and grow from the experience of visiting its galleries.

Peter Hassrick was Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar for the Center of the West. A prolific writer and speaker, he was honored by the University of Wyoming with an honorary doctorate degree in 2017. He served as guest curator of numerous exhibits nationally and internationally. He was a former twenty-year Executive Director of the Center of the West and served tenures directing the Denver Art Museum’s Petrie Institute of Western American Art, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, as well as worked as collections curator at the Amon Carter Museum. Hassrick passed away in 2019.

Post 260

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.