Western American Art Reinterpreted – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2009

See the West in a Whole New Way: Western American Art Reinterpreted

Ed. Note: A look back to an article on the Whitney Western Art Museum’s complete redesign and reopening in 2009.

By Mindy A. Besaw

A celebration 50 years in the making

Over the last fifty years, the Whitney Western Art Museum’s extraordinary collection has shared the inspiration and grandeur of the American West with millions of visitors. Part of the celebration of the Whitney’s 50th anniversary involves a renovation of our galleries and reinstallation of our world-class collection where visitors will “see the West in a whole new way.”

The Whitney Museum collection presents masterworks of western art dating from the early 1800s to the present. The AmericanWest inspired all of the artists represented in the collection, and their work tells stories of the West that highlight wildlife, landscapes, people, and events.

The new installation departs from a conventional chronological survey of western artists and instead is organized around themes and narratives where historic and contemporary art are intermixed. Interactive educational elements throughout provide visitors with opportunities to learn more about the art and artists, offer a forum to present differing viewpoints and opinions, encourage connections with the art, and promote moments of discovery. The installation aims to provide visitors with new perspectives on the role of art in shaping how we view the American West.

Western experience

This introductory theme explores how artists have played a major role in interpreting and promoting the natural grandeur and wild adventure of the West. For viewers in other parts of the world, the art offered a glimpse of western land and life they had no other way to see. Tourists were drawn westward by the romantic and exciting images created by artists. Because of the artwork, the West was, and still is, a popular destination for artists and travelers searching for the western experience—picturesque landscapes, untamed wildlife, and the action and adventure of cowboy life.

In 1904, N.C. Wyeth made his first trip out West. He worked for three weeks on a cattle roundup in Colorado. After Wyeth returned to Delaware, he completed a series of paintings to accompany an article about his experience. Wyeth’s 1904 western adventures acted as inspiration for many paintings in the years that followed. Rounding Up is one of the seven paintings in the series.

Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran was the artist whose nickname spoke volumes about his close ties to Yellowstone National Park. He first painted Yellowstone while on an official government expedition to the region in 1871. After a return trip in 1892, he painted more views of the park, including one of a pass called Golden Gate. Moran’s images of Yellowstone were widely distributed in the United States and were the reason many tourists made the arduous journey to the park in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Wonders of wildlife

The monumental sculpture Testing the Air, by T.D. Kelsey, draws visitors into the section focused on the wonders of wildlife. Here we examine artists’ portrayals of animals and their influence on how we view wildlife in art. Artists develop a connection with wildlife to bring out qualities of the animals they admire and respect—qualities that then become commonly associated with them.

For example, Eli Harvey created Bull Elk for the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The Elks chose the western animal as their symbol in 1868. They described the elk as noble, peaceful, majestic, and keen of perception. These are the characteristics they wanted to encourage in their organization.

In a niche of this section, visitors can compare small sculptures of animals by many artists. Charles M. Russell, Alexander Phimister Proctor, T.D. Kelsey, and George Carlson were all inspired by the wildlife and horses of the West. The variety of styles and expressions on a similar scale is certain to be interesting and engaging.

Horses in the West

Naturally, horses are highlighted as one of the most identifiable symbols of the West. Wild horses exemplify the freedom and exhilaration of western life, while domestic horses represent a necessity as well as a constant companion for working cowboys. The artwork featuring horses also demonstrates the variety of ways artists are inspired by this single animal. Artists depict the horse in many types of media—oil paint, bronze, and clay; and multiple styles—from realistic portrayals to modern and abstract versions.

Inspirational landscapes

The overwhelming power of the grand panoramas of the West has drawn artists to this region for hundreds of years. But, is the West always picturesque and idyllic? Because we often view the landscape through the artist’s eye, we are influenced by his or her point of view. Nineteenth-century landscape painters depicted the West as untouched, fertile, and awaiting settlement. However, in many cases the land was dry and difficult, or already inhabited. Even today, artists often choose to ignore elements such as roadways in favor of a pristine view. Still, whether real or imagined, landscapes remain inspirational.

Wilson Hurley’s large-scale painting, View from the Mohave Wall, is displayed in a wide-open space ideal for viewing it from a distance and “up close and personal.” Hurley frequently visited the Grand Canyon and painted the landscape of the region, and this painting captures a moment in time when light illuminated the chasm. Hurley wrote, “The Grand Canyon is never the same, but like the sea, is always changing color and shadows with the hours, the daily weather, the seasons.”

First people of the West

For nearly two hundred years, artists have been fascinated with American Indians. Even though they worked from many points of view, the artists depicted the Indians with characteristics and clothing that varied little in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They chose unique aspects of Native American features and dress—braided hair, feather bonnets, and colorful beaded moccasins—and made them the common elements for depicting Indians in art. Viewers now associate these aspects (primarily from Plains Indian culture) with all American Indians. However, while the “visual vocabulary” remained similar among artworks, there are also important differences that often tell deeper stories.

For example, Indian Warrior by Alexander Phimister Proctor utilizes clothing such as an eagle feather headdress and beaded moccasins for the noble and majestic figure astride his horse. Almost a hundred years later, Kevin Red Star used similar features in his bold and modern painting, Crow Indian Parade Rider. Red Star researches the culture, clothing, and history of his tribe, the Crow, for his paintings. He exaggerates color and simplifies form to enhance the brilliant glimpse of Crow life. The attributes offer similarities for the comparison of the two works, but the differences in style, time period, and culture offer rich context between the two.

On one hand, Proctor’s classic sculpture of the mounted Indian emphasizes the artist’s formal academic art training. In the subject, Proctor was searching for something that would personify the ideal of the American West for the early twentieth-century audience. The Indian Warrior embodies the qualities of beauty, elegance, strength, and nobility he desired. Red Star’s style reflects a contemporary, expressionistic sensibility. Here, the subject is personal because it celebrates Red Star’s Crow Indian cultural heritage. From the title we also know that the figure is a parade rider, giving the viewer a setting for contemplating the painting.

Heroes and legends

Artwork featuring Buffalo Bill, General Custer, pioneer women, cowboys, and trappers are placed within the theme “Heroes and Legends.” This section illustrates the romantic images of western people and historical events created by artists who use unique features to depict the people of the West. For example, we recognize Buffalo Bill because of his hat, goatee, long hair, and unique dress—evident in a group of paintings and sculptures of the legendary showman.

We should remember that artists also make choices that influence our view of people and events. The grueling condition of pioneer families and cowboy life is often omitted. Instead, a pioneer woman might be portrayed as angelic and innocent, as in W.H.D. Koerner’s Madonna of the Prairie. The covered wagon is a halo framing the young woman’s head. Whether depicting real or mythical figures, visual images influence our ideas and perceptions of those people.

The heroic cowboy

The hardships, joys, excitement, and tranquility of cowboy life are inspirational to artists. One element captured repeatedly is the rider and bucking bronco. The cowboy breaking the wild horse is uniquely American and depicts the classic struggle between man and animal. Since the earliest version by Frederic Remington, other artists have risen to the challenge of capturing the action and tension of cowboy and horse. Many variations of the subject in two and three dimensions re-emphasize the appeal of the cowboy in art.

Behind the scenes: the creative process

Looking at an artist’s creative process connects us to the artwork. Through the creative process, viewers gain an understanding of how the art was made, and an artist’s individuality is revealed. Art begins with inspiration and culminates with the finished work. But in between, an artist can be inspired by western experiences, inspirational landscapes, and encounters with people. He or she may then conduct research, prepare sketches and studies, and finally begin painting or sculpting. In art galleries, the final masterwork is usually the only part of the process a viewer ever sees. In this section of the Whitney, many stages of the creative process are revealed.

A major strength in the Whitney is our studio collections of Frederic Remington, W.H.D. Koerner, Joseph Henry Sharp, and Alexander Phimister Proctor. The re-created studio of Remington offers a glimpse into what inspired the artist. Remington’s studio is a treasury of the many objects he collected on his numerous travels to the West and other parts of the world, as well as many oil sketches. New this year, visitors can get closer to the objects because they can walk into the studio. An additional narrative about the studio and a touch screen interactive kiosk featuring selected objects offers more opportunity for learning about Remington and his studio.

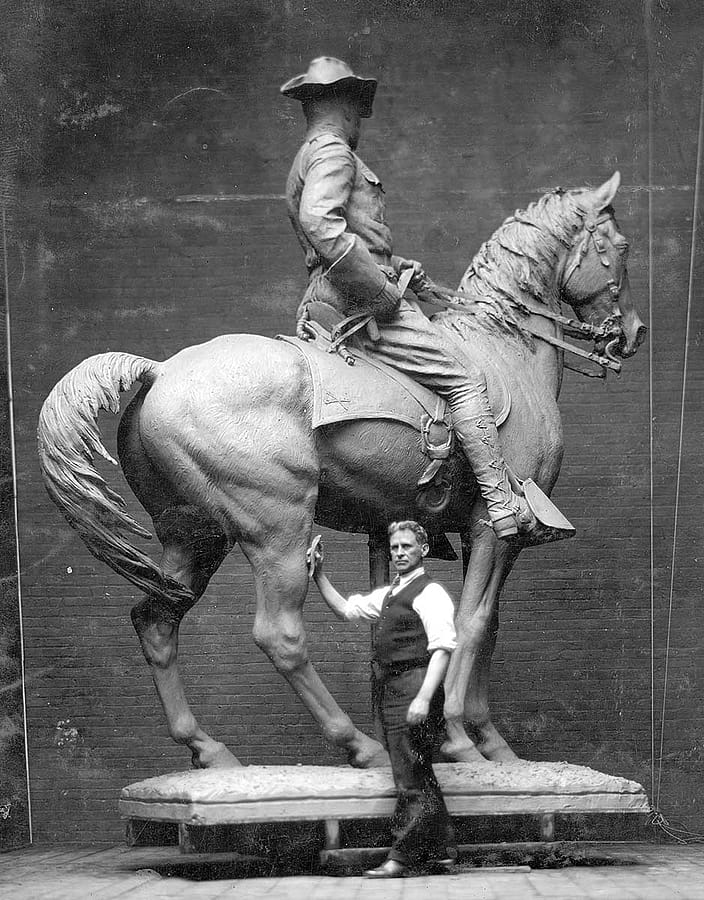

In addition to the Remington studio, a newly renovated area within the Whitney Museum presents the re-created studio of Alexander Phimister Proctor. The objects there present the working process of the sculptor. The highlight and draw of the area is sure to be the plaster pieces relating to Proctor’s fifteen-foot tall monumental sculpture of Theodore Roosevelt, Rough Rider. Again, the studio is designed as a walk-through space where visitors can immerse themselves in Proctor’s artwork, with more than eighty original works by the artist on view.

“Behind the scenes” gives the art context, encourages discovery, challenges perceptions, and ultimately allows contemplation.

The ‘”new” Whitney

New interpretation not only persuades visitors to think about how art shapes their views of the American West, but helps them to see old masterworks in a new light.

This juxtaposition of art from across time and culture presents multiple perspectives on the subject. Multiple perspectives generate a new dialogue between artworks, and with viewers. We hope the installation reminds visitors that there is no one way to view a subject—like American Indians or cowboys or wildlife—and no one way to interpret the artwork. As you visit the extraordinary Buffalo Bill Center of the West, come see the Whitney Western Art Museum, and you can judge for yourself!

At the time this article was first published, Mindy A. Besaw was the John S. Bugas Curator of the then-named Whitney Gallery of Western Art.

Post 261

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.