From “Thorofare” to Destination: The South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2017

From “Thorofare” to Destination – the South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 1

By Jeremy M. Johnston, PhD

There was a reason that William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody located his beloved TE Ranch along the South Fork of the Shoshone River: It’s a beautiful area, steeped in history—like no other place in the West. As the Center of the West commemorated its Centennial in 2017, Curator Jeremy Johnston of the Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum, now the Center’s Historian, shared a story integral to the celebration—one that preceded it by a couple hundred years.

…history is a pontoon bridge. Every man walks and works at its building end, and has come as far as he has over the pontoons laid by others he may never have heard of. Events have a way of making other events inevitable; the actions of men are consecutive and indivisible. –From Wolf Willow by Wallace Stegner

Climate, altitude, geology, precipitation, and many other natural forces combine to shape landscapes; yet historical land use also plays a significant role in developing landscape and the lifestyles of its residents. The South Fork of the Shoshone River in northwest Wyoming has its own unique character when compared to other regions within the Yellowstone Ecosystem: isolated, the end of the road, a retreat. It is not a thoroughfare like the North Fork of the Shoshone on the other side of the Absarokas; traffic along the South Fork rarely just passes through.

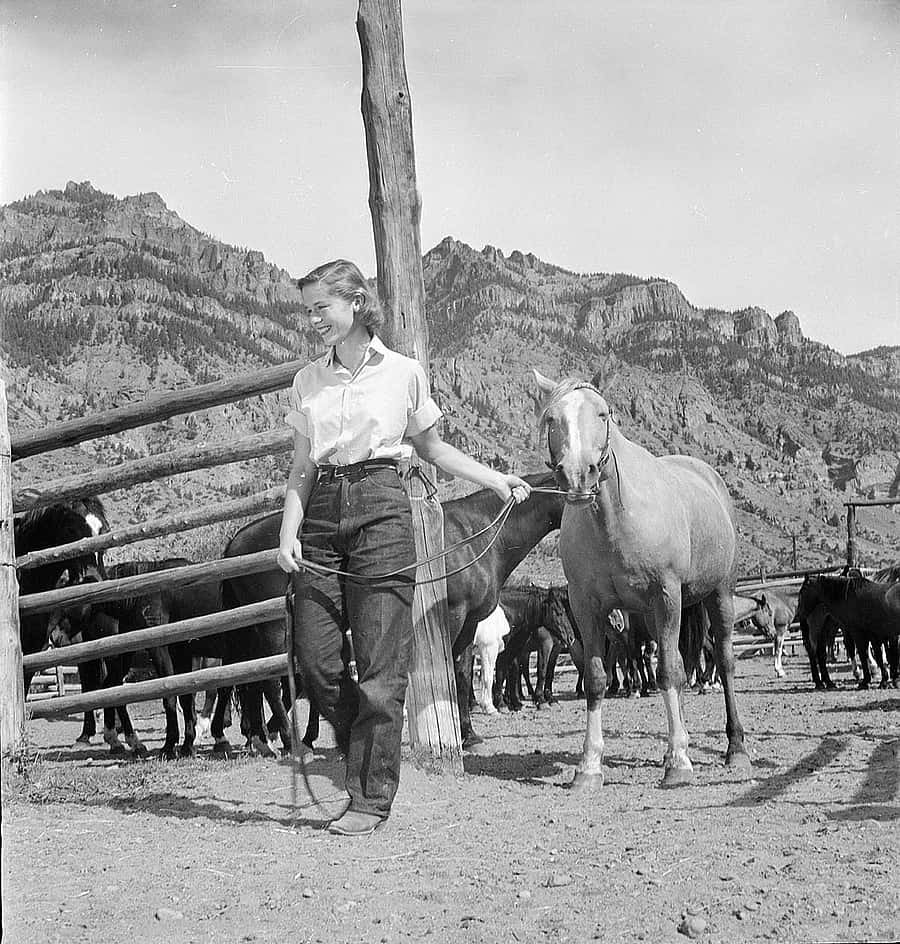

This landscape attracted the likes of dude rancher Larry Larom, allowing him to introduce many young boys and girls from the cities to the “Old West.” This is where Anson Eddy lived as a mountain man well into the 1970s. The following experiences and words recorded from past visitors and residents highlight the historical evolution of land use that shaped today’s landscape in both the South Fork and North Fork valleys.

If we go back centuries, we notice that the South Fork of the Shoshone was a relatively busy place with traffic going back and forth, beginning with the American Indians of the region. These original inhabitants established a trail through the South Fork that connected to an extensive network of trails feeding a busy continental trade network. These connections are demonstrated by the presence of Yellowstone obsidian found within the archaeological sites of the early Mound Builders cultures hundreds of miles away in the Midwest.

Europeans plugged into this trade network as they colonized the Southwest and the East Coast. During this historic period, horses found their way to the early residents of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains through these trade routes. These horses transformed footpaths into well-established trails, facilitating trade through the region.

A few remnants demonstrate the South Fork’s international connections from this historical period. Anson Eddy discovered Spanish coins dated 1781 at Crescent Pass, alongside various chips and flakes from early projectile-point makers. More than likely an early American Indian acquired these coins from a trade fair and lost them while passing through the South Fork.

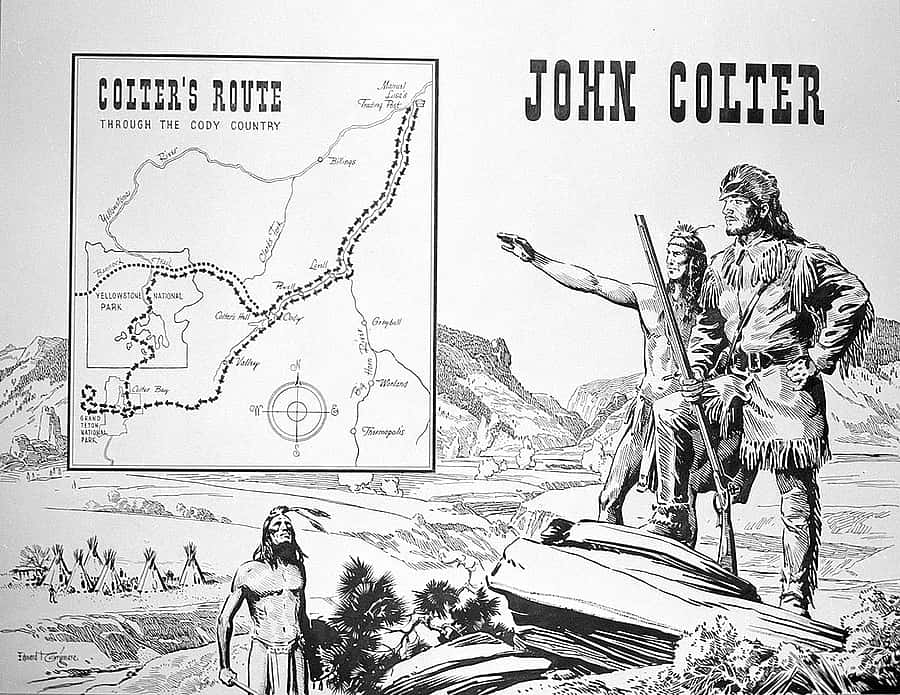

John Colter arrived in the region the winter of 1807–1808 as a representative for the fur trader Manuel Lisa. Colter sought trails to find potential trading partners that could provide beaver pelts to Lisa’s post on the mouth of the Big Horn River in present-day Montana. His geographical information was eventually passed on to his former boss, Captain William Clark, who was producing a map based on his expedition through the American West with fellow commander Meriwether Lewis.

Another Lewis and Clark member, George Drouillard, provided Clark with a rough map based on his travels in the Big Horn Basin. This map reflects the geographical information early fur traders gleaned from their American Indian hosts. The South Fork of the Shoshone River was identified as the Salt Fork of the Stinking Water River. The map also identifies “Hart” Mountain, Spirit Mountain (present-day Cedar Mountain), and the North Fork of the Shoshone named the Grass House River. Notes indicate the North Fork, “reaches to the main mountains or nearby it—requires 12 days march to reach its source—much beaver and otter on it.” The “Salt Fork” is described as “a considerable river.” Although Drouillard identified Heart Mountain as “Hart Mountain,” the published Lewis and Clark map spelled it correctly. A few local historians believed this mountain was named Hart after an early explorer or army officer, but its early use on the Lewis and Clark map indicates it was named through Colter and Drouillard due to its resemblance to a buffalo heart.

Drouillard also identified a “Salt cave on N side of a mountain where the salt is found pure or perfect – the sun never shines – is believed to be fossil salt the Spaniards obtain it from this plaice by passing over the river Colorado—the Indians of the country live on horses altogether.” Drouillard noted that one could reach the Spanish settlements in a “14-day march” from Cedar Mountain or an 8-day trip from the Salt Cave.

To this day, the location of the Salt Cave is unknown. The location and the description of the cave may have been the result of a mistranslation between Drouillard and his American Indian sources. It’s also possible that Drouillard mistakenly believed that some of the region’s mineral deposits from the local geothermal features used by American Indians to treat hides was salt, a common European method for tanning hides.

Despite Drouillard’s enticing information, as far as we know, no expedition ever tried to establish the Santa Fe Trail through the South Fork of the Shoshone. The War of 1812 disrupted the American fur trade, and it was not until the 1820s and 1830s that the American fur traders returned to the area. Fur trapper Joe Meek and a group of trappers camped at “Colter’s Hell” near present-day Cody, Wyoming, in 1830. Meek later noted, “This place afforded as much food for wonder to the whole camp…and the men unanimously pronounced it the ‘back door to that country which divines preach about.’ As this volcanic district had previously been seen by…Colter, while on a solitary hunt—and by him also denominated ‘hell’—there must certainly have been something very suggestive in its appearance.”

Osborne Russell, a fur trader headquartered at Fort Hall along the Snake River in present-day Idaho, used the South Fork corridor hoping to escape a Blackfeet war party. Traveling from Jackson’s Hole, Russell and his companions found themselves traversing the South Fork downstream to Colter’s Hell, carrying a companion wounded in a skirmish with the Blackfeet. Russell detailed their trip as follows:

“We ascended the Mountain…and crossed the divide and descended another [river] branch (which ran in a North direction) about 8 mls. and encamped in an enormous gorge… [July] 19th traveled about 15 mls. down stream and encamped in the edge of a plain. [July] 20th traveled down to the two forks of this stream about 5 mls. and stopped for the night. Here some of the Trappers knew the country. This stream is called Stinking River a branch of the Bighorn which after running about 40 mls thro. the big plains enters the river about 15 mls. above the lower Bighorn Mountain. It takes its name from several hot Springs about 5 miles below the forks producing a sulphurous stench which is often carried by the wind to the distance of 5 or 6 Mls. Here are also large quarries of gypsum almost transparent of the finest quality and also appearances of Lead with large rich beds of Iron and bituminous coal We stopped at this place and rested our animals until the 23d.”

Many years later, on April 13, 1859, Captain William F. Raynolds of the Corps of Topographical Engineers received orders from the Secretary of War to explore the Yellowstone River basin. The overall goal of this expedition was to find possible locations for military roads from Fort Laramie and South Pass in Wyoming to Fort Union and Fort Benton, both along the Missouri River. Additionally, Raynolds was instructed to reconnoiter the mountainous regions that formed the headwaters of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. Along with his enlisted men, the War Department authorized Raynolds to hire up to eight assistants, including a geologist, naturalist, astronomer, meteorologist, and others that would record key scientific information regarding the Yellowstone River Basin.

To map the Big Horn Basin, Raynolds sent an expedition led by Lieutenant William M. Maynadier, who deemed the Absaroka Range nearly impassable for potential travelers. Raynolds concluded in his report, “This part of the country…is repelling in all its characteristics, and can only be traversed with the greatest of difficulty.”

Maynadier explored the lower section of the Shoshone River to locate a suitable ford to cross the deep river. Near present-day Ralston, the men crossed the Shoshone and in the process lost one wagon and a number of supplies. Maynadier noted, “We returned to camp wet, cold, hungry, and dispirited, and I passed the most wretched night it has ever been my lot to encounter.” During his trip through the Big Horn Basin, Maynadier described Heart Mountain as “a mountain capped by an immense square rock, leaning slightly, and forms a prominent landmark.”

Based on his tough trip through the Big Horn Basin, Maynadier reported, “The prairie is too destitute of timber and water to attract or sustain settlers…. The exploration also shows that any route, either for a railroad or wagon road, through the Big Horn mountains, or by the valley of the Big Horn river, is impracticable, except at immense cost.” In comparison, Maynadier described the Yellowstone Valley as not only attractive to future settlers, but also would serve as a good route into the Yellowstone region, additionally, “a road connecting the Platte and the Yellowstone is easy and practicable, but it must go around, and not through, the Big Horn mountains.” According to Raynolds’s report, the Stinking Water River served as a major obstacle, one to be avoided by settlers and travelers, not a thoroughfare as indicated by the American Indians and fur traders.

In the next article in this Points West series, Johnston continues his narrative of the people whose life and times included the South Fork of the Shoshone River. Next time, Jim Bridger. From Thorofare to Destination originated as a presentation to the Upper South Fork Landowners Association, August 6, 2016, at Valley Ranch.

About the author

Dr. Jeremy M. Johnston is now the Center of the West’s Historian, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western American History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody. At the time this series of articles was written, he was also the Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum. His family settled near Castle Rock in the late 1890s. Johnston was born and raised in Powell, Wyoming, attended the University of Wyoming, from which he received his bachelor of arts in 1993, and his master of arts in 1995. He taught history at Northwest College in Powell for more than fifteen years. Johnston earned his doctorate from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, in May 2017.

Post 266

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.