From “Thorofare” to Destination: the South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2017

From “Thorofare” to Destination – the South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 2

By Jeremy M. Johnston, PhD

The South Fork of the Shoshone River, southwest of Cody, Wyoming, was a relatively busy place in the nineteenth century. In the previous issue of Points West, Dr. Jeremy Johnston noted a steady stream of trappers and explorers in the region from John Colter and Jim Bridger, to George Drouillard, Joe Meek, Osborne Russell, William Raynolds, and William Maynadier. But even though so many managed to negotiate both the North and South Forks of the Shoshone River at the time, Raynolds dubbed the area “repelling in all its characteristics” and “only traversed with the greatest of difficulty.”

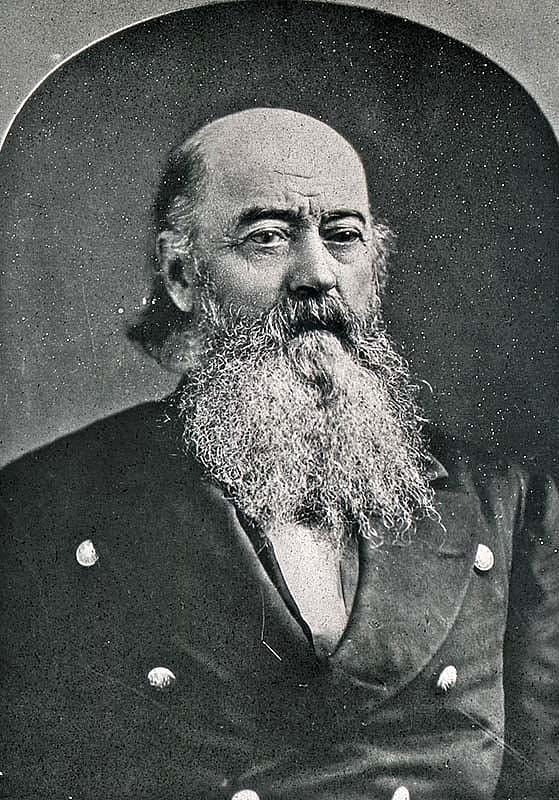

Jim Bridger (1804-1881). Denver Public Library, Call Number: Z-314. Noah H. Rose Collection. Wikipedia.

Jim Bridger (1804-1881). Denver Public Library, Call Number: Z-314. Noah H. Rose Collection. Wikipedia.

In comparison, Maynadier described the Yellowstone Valley as not only attractive to future settlers, but also would serve as a good route into the Yellowstone region, additionally, “a road connecting the Platte and the Yellowstone is easy and practicable, but it must go around, and not through, the Big Horn mountains.”

Johnston continues the story…

William A. Jones

Then, in the summer of 1873, Captain William A. Jones commanded an expedition for the Army Corps of Engineers under orders to explore Yellowstone National Park and locate potential routes to this new federal reserve. Accompanied by Shoshone Indian guides, Jones attempted to pioneer a route to Yellowstone through the Big Horn Basin into the newly-created national park.

Eventually, the party worked its way over the divide between the North Fork and South Fork of the “Stinking Water” (Shoshone) River—named “Ish-a-woo-a” by Jones. As they passed through the area, Jones described their crossing of the river:

“The drift in the valley is composed of the debris of volcanic rock. We passed the remains of a large depositing sulphur spring… It lies close to the Ish-a-woo-a River, on the south side near where our trail crosses, and probably at one time contributed largely to the odorific title of the main river. A few miles lower down, below the canon, a mass of sulphur springs occur which still give good cause for the river’s name…

“The Stinking Water is a river of considerable size, and, probably is rarely fordable below the junction of its two main forks. We had considerable difficulty in finding a ford across the Isha-woo-a, even this late in the season, and probably neither of the forks are fordable much earlier.”

On his way to the North Fork, Jones crossed the South Fork of the Stinking Water River near Castle Rock, dubbed Ishawooa by the Shoshone Indians. On July 26, 1873, he explained, “I have given this stream [the South Fork] the Indian name of a peculiar shaped rock, by means of which they distinguish it. It is a remarkable, finger-shaped column of volcanic rock, standing alone in the valley, about three miles above our crossing.” Eventually, Jones would express concern about this route to Yellowstone. Despite Jones’ concerns regarding the rugged terrain of the North Fork route to Yellowstone, various individuals continued to use the route to traverse from the Big Horn Basin to Yellowstone.

Yellowstone Kelly

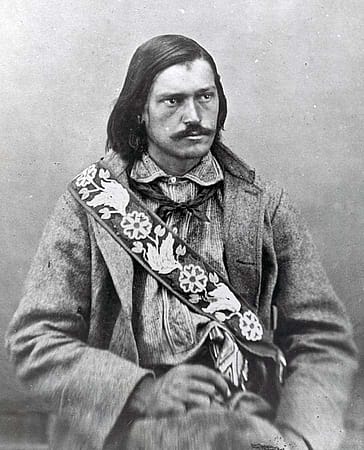

Following the Jones expedition, a number of miners, soldiers, and scouts passed through the North Fork of the Shoshone, despite that foreboding landscape. Luther S. Kelly, “Yellowstone Kelly,” documented this traffic in his memoirs. In 1878, Kelly was ordered to scout the Crow Reservation (Montana) for two reasons: 1) to determine if any gold prospectors were trespassing on Indian lands, and 2) to locate the Bannock Indians, then fleeing their reservation in Idaho by traversing the route the Nez Perce used the preceding year.

Accompanied by two soldiers, Kelly traveled through the Crow Reservation into the Big Horn Basin and up the Shoshone River.

“From Pryor Gap, we passed to the Stinking River Canyon, whose gorge could be seen like a knife-cleft in the side of the mountain. The stream itself, bare of timber, is a beautiful mountain torrent of clear sparkling water where it issues out of the canyon. It receives its name from a small geyser which impregnates the water and the air with sulphureted hydrogen. The walls of the canyon are composed of a beautiful granite, and I noticed a cap of limestone.”

Near the bed of the river, Kelly and his party encountered two prospectors who informed them of a mining party camped near what he identified as “Heart Butte,” likely referring to Heart Mountain. Kelly visited the camp and discovered the mining party suffering because of a rain shower that washed away most of their supplies. Yellowstone Kelly proceeded back to the mountains and decided to travel the North Fork route to Yellowstone.

“I quickly decided that this valley was the course to the [Yellowstone] lake, and surmised that it could not be more than twenty miles beyond where our view terminated. [Continuing to Yellowstone along the North Fork, Kelly and his companions encountered a group of soldiers from Fort Washakie searching for two deserters.] Winding along the north fork of this mountain stream was a pleasant diversion, for here the game trails led, ever upward, through the cool sequestered woods of pine and aspen which bordered the tin streams. Early in the afternoon we camped in a little park of grass and flowers and feasted on coffee, trout, and venison, flanked by cans of condensed milk and currant jelly.”

Many like Yellowstone Kelly found it to be not only a scenic route, but a passable trail from the Big Horn Basin to Yellowstone National Park.

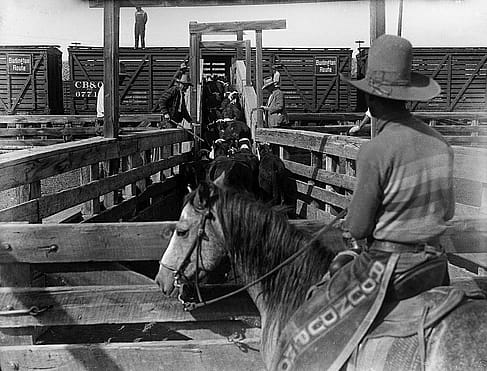

By the early 1880s, hide hunters decimated the bison herds in the Big Horn Basin, leaving a wide-open grazing landscape for livestock. While a handful of miners passed through the region after the fur trade, there were no major gold strikes in northwestern Wyoming. However, the discovery of gold created mining communities in other regions of Montana and Idaho territories, creating a demand for food, especially beef. Additionally, after the Civil War, expanding urban markets demanded cattle products in the East, and Wyoming entered its cattle ranching phase. The South Fork area shifted from the fur trade to cattle ranching, making it a destination for ranchers, and changing its status as a thoroughfare for people traveling through to other locations.

Carter cattle

According to a letter dated September 14, 1941, addressed to local cowboy and historian John K. Rollinson, William Carter—the son of William A. Carter who sent in the first herd of cattle to the South Fork—detailed the early history of ranching in the region. He noted that his father often purchased cattle, once destined for market, that had become weak or lame from cattle drives. They would form the foundation of his herd.

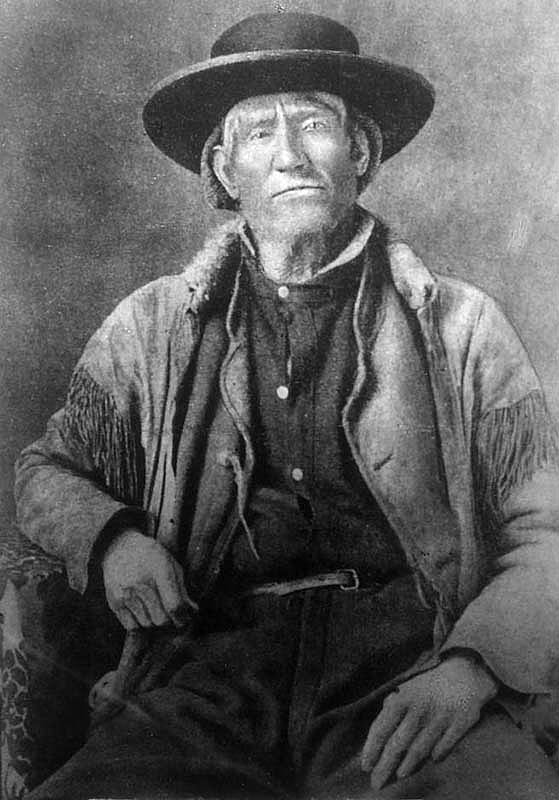

My father sent about two thousand Oregon cows, with bulls bought in Missouri, in charge of Peter McCulloch to the Stinking Water range, in 1879. It was in 1879 that Shoshone Chief Washakie recommended the move to him. Washakie did not come to Bridger, nor did my father go to look at the country. The advice was given through Mr. James K. Moore, post-trader at Ft. Washakie, who had formerly managed a store for my father, at Camp Brown, near what is now Lander.

The herd that the elder Carter sent in 1879 was the first outfit to locate on the Stinking Water. After his father’s death in 1881, the younger Carter sent a second drive of about two thousand cattle to Stinking Water in summer 1883 due to the dry season and overcrowding of the range in southwest Wyoming. By this time, McCulloch had quit and moved to farm in Iowa to be near family. Carter and another rancher in the area named McCulloch’s Peak [McCullough Peaks], northeast of Cody, after him.

It is worth noting that the Carter Cattle Company began referring to the Stinking Water River as the Shoshone River. During the summer months of 1887, they advertised their brand in the Northwestern Live Stock Journal, published in Cheyenne, Wyoming. There, they identified their cattle in the South Fork as the “‘Shoshone River Herd,’ range on Shoshone or Stinking Water River and tributaries east of Yellowstone Park.”

Due to Chief Washakie’s recommendation that the elder Carter establish a ranch along the South Fork of the Stinking Water River, it is very likely the herd was named in honor of Washakie’s people. Carter Mountain was named in honor of the elder Carter of Fort Bridger.

Gillette and the Burlington Railroad

As cattle ranching went through various booms and busts in the American West, other businesses focused on possibilities for the South Fork. With the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, and the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883, tourists poured into northwest Wyoming. Other railroads sought to establish connections to Yellowstone to reap their share of the profits. Once again, the South Fork was viewed as a potential transportation corridor. In 1891, Edward Gillette of the Burlington Railroad led a survey up the South Fork of the Stinking Water River, only to discover this region proved challenging to any railroad construction. He described his visit as follows:

“We located the line up the north bank of the Shoshone River, through the places now occupied by the towns of Byron, Garland, Powell, and Cody. Between Byron and Garland, gas was escaping from the ground, and a piece of pipe driven into the ground would fill with it, which would burn with a steady flame. At the present time the greatest producing gas wells in the state are in operation here, and there is also quite a production of oil. Our survey crossed the river near Corbett, to the south of Cedar Mountain; thence up the South Fork.

“The Sulphur Springs near where Cody is located seemed an off-shoot from Yellowstone Park. Gas was escaping from holes along the cañon above; small animals and birds in considerable numbers had been suffocated by the gas, and it was dangerous for a person to breath it.

“In the first cañon on the South Fork, we found some lettering on the trees, made by prospectors in early days, and later on found the remains of old beaver traps.

“The elk trails, in places where the canon narrowed, were not wide enough for pack animals. One of the settlers, named Legg, while driving his horse along one of these trails, it not being safe to ride, was unfortunate enough, at a particularly bad place where there was a sheer drop of a hundred to two hundred feet, to run onto a bull elk coming in the opposite direction. The elk promptly hooked the horse off the trail and the hunter shot the elk which fell beside the horse, both being killed. We blasted out the trail wide enough for our animals, but always arranged the packs as high as possible. The elk trails crossed immense rock slides, the rocks coming from small openings high up the mountains, and it must have taken centuries to build up such enormous dumps.

“In places, the game trails were buried by constantly sliding rocks, and, in crossing such places, it was safer to walk than to ride. One night when crossing these slides, leading an animal which had run away and been found in the valley below, I concluded not to dismount. As luck would have it, the led animal got the rope under my horse’s tail and he commenced to buck. We were soon going down the slide, half-buried in rocks and it was a long time before we were able to regain the trail.

“Trout were abundant in the stream until we had passed the second canon where a waterfall had practically checked the fish, though a few trout were found above. The boys had brought so many trout to camp that we had fish every day; in fact, it seemed as though we had them every meal. Feeling the need of fresh meat and not being quite in the elk country, we sent down in the valley for a hind quarter of beef. Everyone gladly helped himself liberally to a steak, but seemed unable to masticate it. They looked at one another in a peculiar manner; finally, one of the boys took a trout, and his example was soon followed by all the rest at the table. Our jaws were weak on account of having eating trout so long; besides the beef was tough.”

After braving the South Fork trails and gorging on fish, Gillette and his party made it to Jackson Hole, and then traveled down the Greybull River to visit Colonel William A. Pickett at his ranch where they were entertained by his bear hunting stories. The party returned to Jackson, then traveled north to Yellowstone Park where they ran into Theodore Roosevelt, then Civil Service Commissioner, who was returning from an elk-hunting trip near Two-Ocean Pass. One can assume they reported their South Fork experiences to Roosevelt, noting the rough trails and the plethora of fish, depicting the South Fork as an isolated paradise providing wonderful fishing and hunting opportunities.

Did Theodore Roosevelt ever travel through the area of the South Fork of the Shoshone River? To find out, read Johnston’s third and final installment of this series in next week’s Points West Online post. (From Thorofare to Destination originated as a presentation to the Upper South Fork Landowners Association, August 6, 2016, at Valley Ranch.)

About the author

Dr. Jeremy M. Johnston is now the Center of the West’s Historian, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western American History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody. At the time this series of articles was written, he was also the Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum. His family settled near Castle Rock in the late 1890s. Johnston was born and raised in Powell, Wyoming, attended the University of Wyoming, from which he received his bachelor of arts in 1993, and his master of arts in 1995. He taught history at Northwest College in Powell for more than fifteen years. Johnston earned his doctorate from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, in May 2017.

Post 267

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.