From “Thorofare” to Destination: the South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 3 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2018

From “Thorofare” to Destination – the South Fork of the Shoshone River, part 3

Click here to read Part 1 and Part 2

By Jeremy M. Johnston, PhD

As we’ve learned, the South Fork of the Shoshone River—southwest of Cody, Wyoming—was a busy place in the nineteenth century. In the last two issues of Points West, Dr. Jeremy Johnston has shared stories from this area—a colorful history of characters and landscapes.

Johnston based this series on a presentation he made to the to the Upper South Fork Land Owners Association on August 6, 2016, at Valley Ranch. At the time, he told the group, “As members, all of you are aware how truly blessed you are to own and live on a little piece of heaven. The South Fork is a wonderful, unique paradise that few people in the world today experience.” And these installments have shown the reader why…

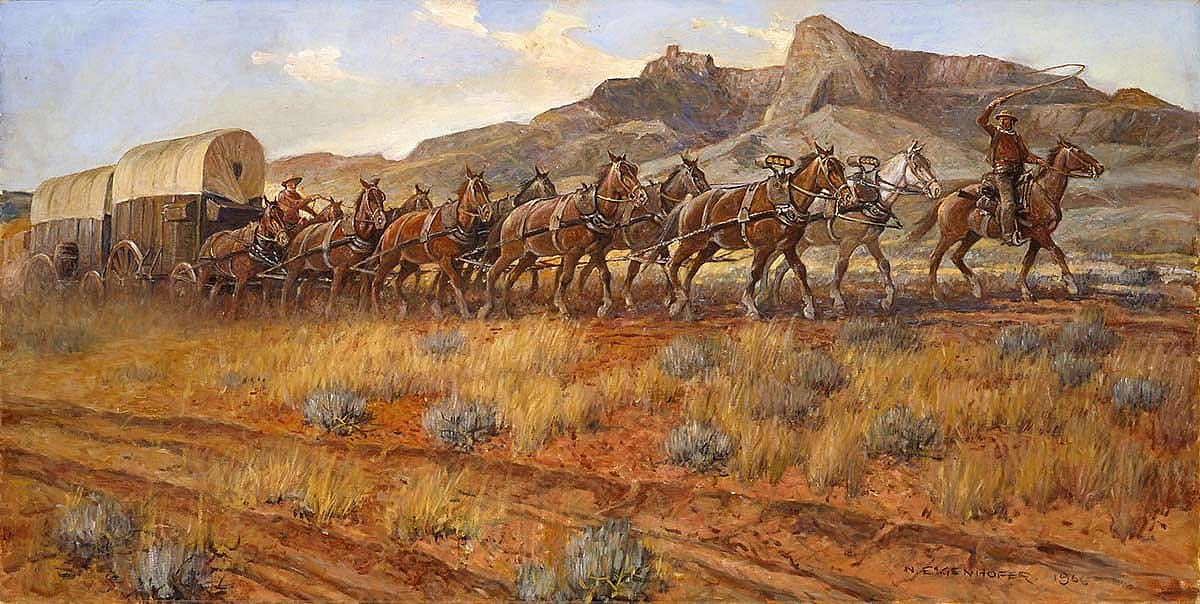

One New Yorker who was attracted to the region for its hunting potential was Archibald Rogers who noted the following as he crossed the Big Horn Basin:

The great main range of the Rocky Mountains stretches before us, its rugged snow-capped peaks glistening in the morning sun, and we long to be there; but many a long mile still intervenes, and forty-four miles of desert have to be crossed to-day. This is always an arduous undertaking. It is monotonous in the extreme, and men and animals are sure to suffer for want of good water; for after leaving Sage Creek on the other side of the Gap, there is no water to be had until Stinking Water River is reached. But all things must have an end; and at last, late in the evening, we find ourselves encamped on the banks of that stream, beautiful despite its unfortunate name.

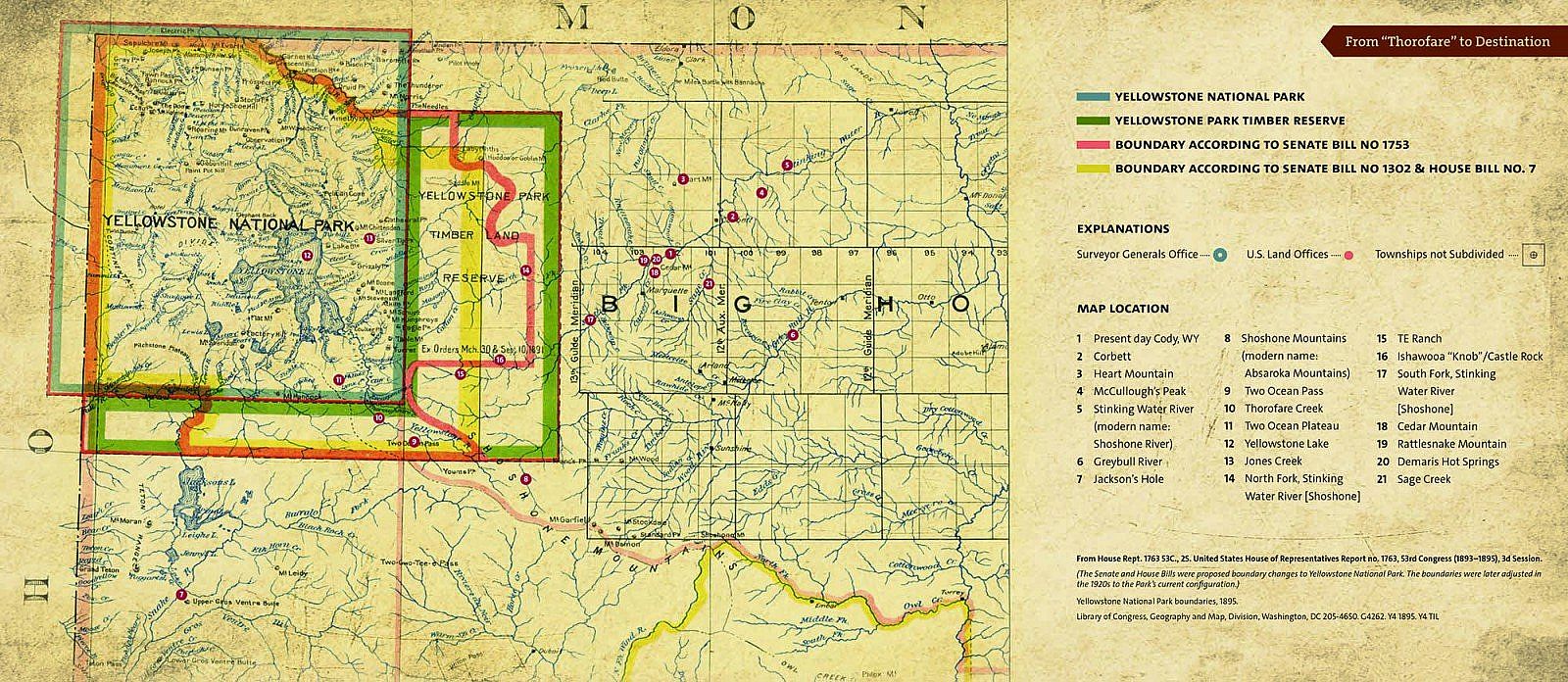

There is little evidence to support the idea that Theodore Roosevelt hunted along either the North Fork or South Fork of the Shoshone River. His published hunting accounts indicated he hunted in the Hoodoo Basin, then located outside Yellowstone National Park boundaries, north of the Shoshone drainage.

In 1897, Roosevelt wrote to internationally renowned sport hunter Frederick Courtney Selous who was then planning a hunting trip to the South Fork. Roosevelt shared with Selous his knowledge about northwest Wyoming:

Unfortunately I can’t give you definite information about the passes of which you speak, because I have never come into country quite the way in which you will have to come into it; but Archibald Rogers has two or three times been over the Stinking Water with a pack train, so I know you can get in from that side… You must remember that it is quite a trip down from the Big Horn mountains into and across the Big Horn valley and up to the Jackson’s Lake country… The best place I know for [bighorn] sheep is just east of the Yellowstone Park.

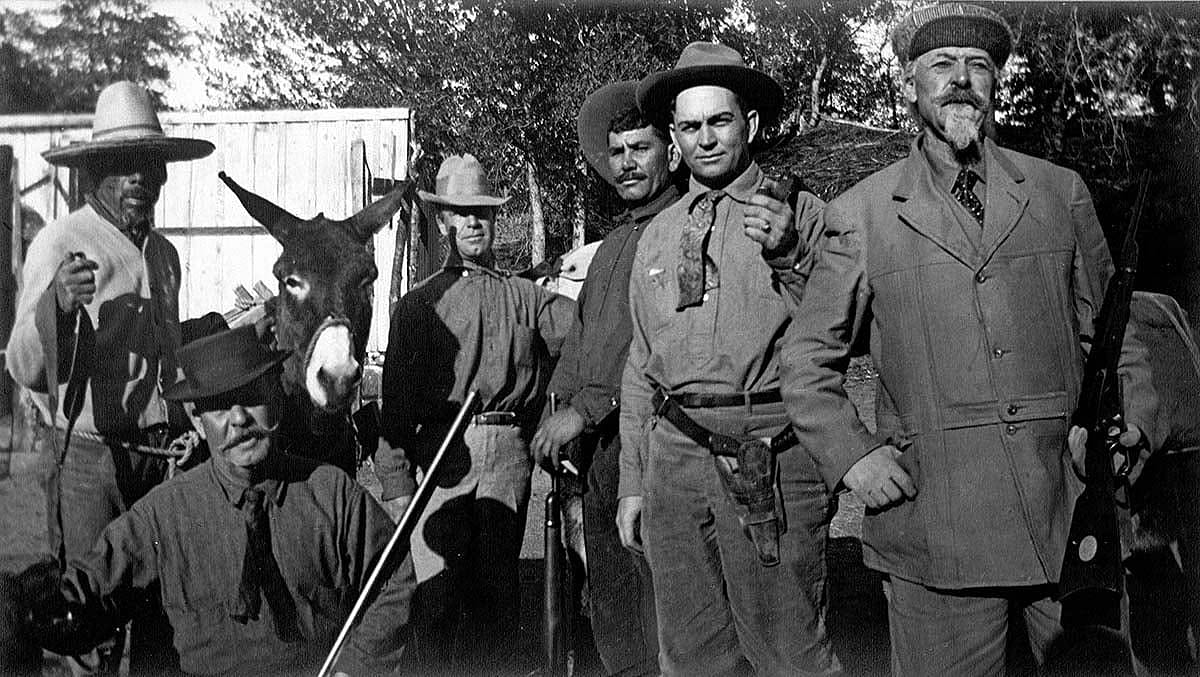

Then, in the fall of 1897, Frederick Courtney Selous arrived in Wyoming, and he described the South Fork region this way:

The North and South Forks of the Stinking Water meet just above the Cedar Mountain and then run in one rushing stream through a deep canyon which divides the last spur of the Rattlesnake Mountains from the main range. A little below the gorge there are some very remarkable hot sulphur springs, some of which are situated just at the edge of the river, whilst others come bubbling up to the top of the water from the bed of the stream of itself. The smell of these sulphur springs is very strong, and it is perceptible at the distance of several miles down wind. To this fact does this beautiful clear mountain stream owe its unsavoury name, Stinking Water being the literal translation of its old Indian designation. The sulphur springs, of which I have spoken, are now known to possess medicinal properties of a very useful nature. Their temperature, which is exactly blood heat, – ninety-eight degrees, – never varies, summer or winter. If all I heard concerning the curative properties of these springs is true, – they are said to be specially [sic] efficacious in cases of chronic rheumatism and syphilis – invalids will soon be resorting to them from all parts of the United States, if not from Europe. Already the world renowned Colonel William Cody has started a small township in their vicinity named after its founder “Cody City,” whilst a small house of accommodation and a plank-built bathroom, heated with a stove in the winter, have been put up at the Springs themselves.

Both the North and South Forks of the Stinking Water River, clear cold mountain streams of purest water, are full of delicious trout. They contain greyling, too which I thought very good eating, though locally they are not much esteemed. The trout are not able to get more than two-thirds of the way up the South Fork, owing to the fact that they cannot pass a certain small waterfall; but whenever we were camped near the water below this fall we could always secure a good dish of trout for breakfast or dinner. They were uneducated fish—which is what I like—and when on the feed would rise readily at almost any kind of fly.

Although greatly impressed with the scenery and fishing, Selous was concerned by the lack of game in the region. He noted in his 1900 hunting account, Sport and Travel: East and West, settlers and sport hunters were over hunting the region. Selous reported a conversation with a South Fork settler from Texas by the name of Timberline Johnson:

A discussion having subsequently arisen concerning the game laws of the State of Wyoming, Mr. Johnson frankly confessed his ignorance on this subject. “He’d heard tell,” he said, “that there were game laws, but they’d never troubled him much.” One of our men then expressed the opinion that all game laws in the United States were unconstitutional, as then game belonged to the people. Naturally, with such ideas abroad, the game is rapidly decreasing in this part of America, nor would it be possible to enforce the laws without the assistance of a very large staff of officials; for you can’t prevent men from shooting wild animals in a wild country where otherwise no fresh meat is obtainable; and my sympathies are with the settlers in this matter, as long as they are not wasteful…

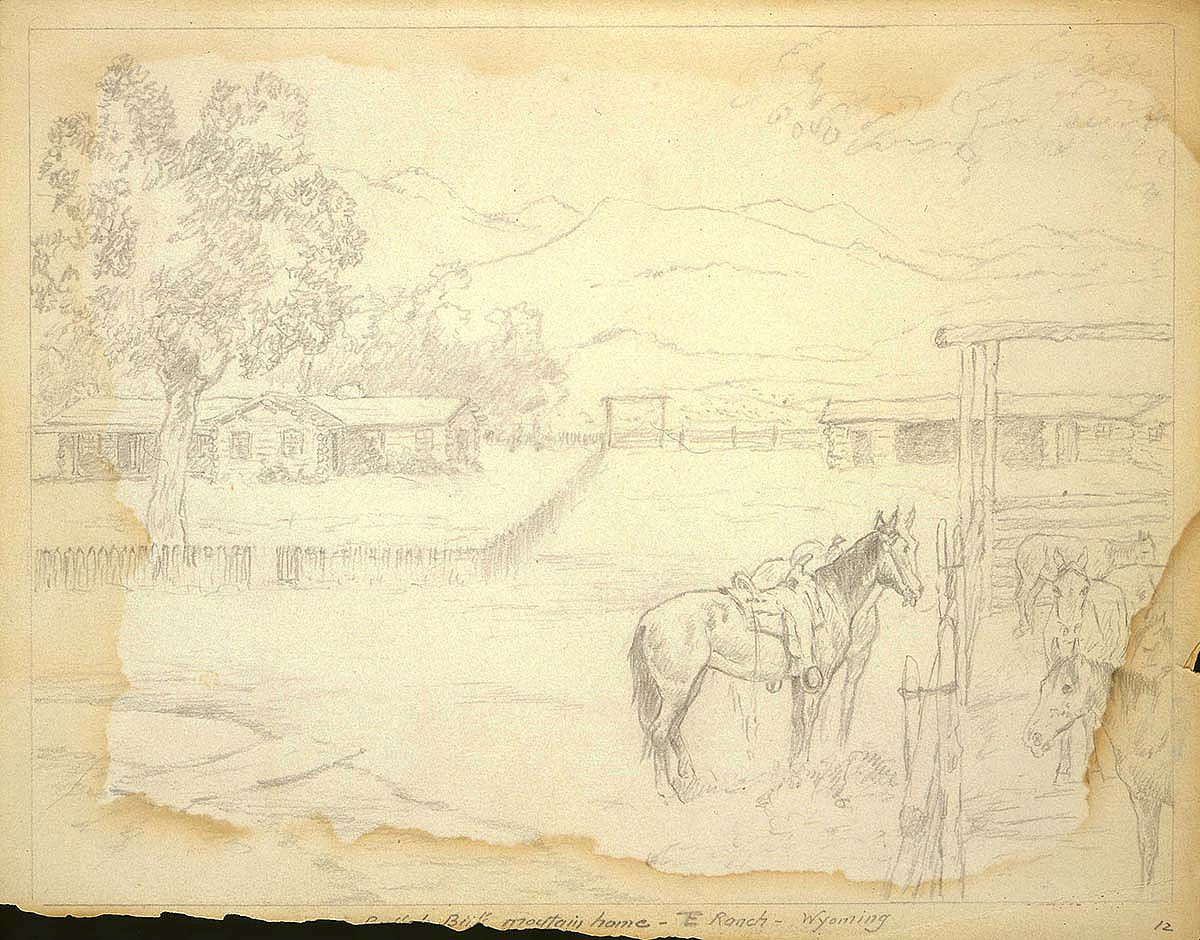

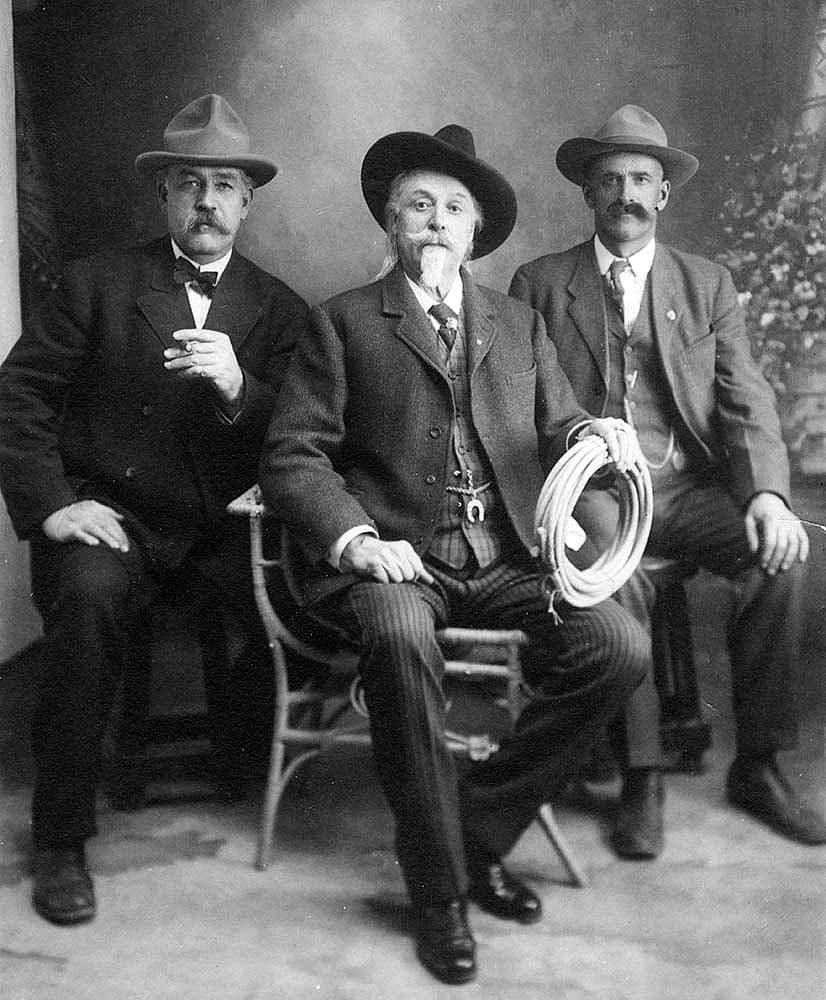

Late in 1894, an international celebrity arrived in the Big Horn Basin for his first visit and decided to invest in the region, a decision that brought intense worldwide attention to the South Fork. South Fork. (Cody’s dates and stories changed through the years. As far as we can determine, he first visited the region in 1894.) William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody noted the potential for ranching and outdoor sports during his first visit. Soon he purchased the Carter Ranch and the TE Ranch. Eventually, he would sell the Carter Ranch to William Robertson Coe, yet he retained the TE Ranch as a working ranch and a private retreat from his busy performance schedule.

Credit for bringing Buffalo Bill to this region belongs to George W.T. Beck, who lured him to the basin to advance a proposed reclamation project that resulted in the establishment of the town of Cody, Wyoming. Beck rightly believed that Buffalo Bill’s tremendous marketing machine would lure potential settlers to the Stinking Water valley. An example of this dynamic marketing scheme is found in Helen Cody Wetmore’s biography of Buffalo Bill titled Last of the Great Scouts.

Wetmore detailed a tall tale told by her brother regarding his first view of the Bighorn Basin. Buffalo Bill claimed he first learned of the region in the 1870s and visited the area in 1881. According to the story, Buffalo Bill suffered from an eye infection. The doctor prescribed washing the eyes with alcohol, but Buffalo Bill did not want to waste whisky so he bandaged his eyes instead.

Upon reaching the Bighorn Mountains, Buffalo Bill claimed his guide washed his eyes with medicinal spring water—residents of Thermopolis claimed the water came from their hot spring; Cody residents claimed it came from DeMaris Springs located within Colter’s Hell, west of Cody. With his eyes cleared by the healing properties of the spring water, he first viewed the Basin. His sister detailed the scene in the biography of her brother:

Off came the bandage, and I shall quote Will’s own words to describe the scene that met his delighted gaze:

To my right stretched a towering range of snow-capped mountains, broken here and there into minarets, obelisks, and spires. Between me and this range of lofty peaks a long irregular line of stately cottonwoods told me a stream wound its way beneath. The rainbow-tinted carpet under me was formed of innumerable brilliant-hued wild flowers; it spread about me in every direction, and sloped gracefully to the stream.

Game of every kind played on the turf, and bright-hued birds flitted over it. It was a scene no mortal can satisfactorily describe. At such a moment a man, no matter what his creed, sees the hand of the mighty Maker of the universe majestically displayed in the beauty of nature; he becomes sensibly conscious, too, of his own littleness. I uttered no word for very awe; I looked upon one of nature’s masterpieces.

Instantly my heart went out to my sorrowful Arapahoe friend of 1875 [who informed Buffalo Bill of the Big Horn Basin]. He had not exaggerated; he had scarcely done the scene justice. He spoke of it as the Ijis, the heaven of the red man. I regarded it then, and still regard it, as the Mecca of all appreciative humanity.

To the west of the Big Horn Basin, Hart Mountain [sic] rises abruptly from the Shoshone River. It is covered with grassy slopes and deep ravines; perpendicular rocks of every hue rise in various places and are fringed with evergreens. Beyond this mountain, in the distance, tower the hoary head of Table Mountain. Five miles to the southwest the mountains recede some distance from the river, and from its bank Castle Rock rises in solitary grandeur. The name indicates, it has the appearance of a castle, with towers, turrets, bastions, and balconies.

Grand as is the western view, the chief beauty lies in the south. Here the Carter Mountain lies along the entire distance, and the grassy spaces on its side furnish pasturage for the deer, antelope, and mountain sheep that abound in this favored region. Fine timber, too, grows on its rugged slopes; jagged picturesque, rock-forms are seen in all directions, and the numerous cold springs send up their welcome nectar.

Although he praised the scenery, Buffalo Bill was greatly concerned regarding the future of wildlife and sport hunting in northwest Wyoming. Buffalo Bill became a strong advocate for protection of the region’s wildlife and the establishment of state game preserves, which was critical to the financial success of his investments in tourism and the promotion of sport hunting. In an article titled “Preserving the Game,” which appeared in the June 6, 1901, issue of The Independent, Buffalo Bill noted:

The condition of game laws in the West is now very satisfactory, and we can confidently look forward to a rapid increase in the number of elk, mountain sheep, deer, antelopes, and all the smaller game, such as ducks, geese, grouse and sage hens.

About three years ago the agitation for game protection in the West began to have good results, and since then Legislatures have passed strict laws and enforced them. Game wardens have been appointed by the various Governors, and men caught violating the laws have been severely punished. It is too late, now, to save the buffalo, but all other game we can preserve.

In addition to advocating for greater game protection, Buffalo Bill also lobbied to officially change the name of the Stinking Water River to Shoshone. In 1901, a few years after settlers homesteaded the region and the town of Cody emerged, State Senator of Big Horn County Atwood C. Thomas introduced a successful bill in the Wyoming State Legislature to rename the river “Shoshone.”

In 1919, the Park Service advocated constructing a road from Jackson, through the Thorofare region, down the South Fork, to Cody, Wyoming. This highway would bring in auto tourism to the region, resulting in various concessions along the South Fork of the Shoshone River, once again promising the region would become a main transportation route, similar to the North Fork highway to Yellowstone.

Due to intense opposition, Stephen Mather, Director of the National Park Service, changed his mind, stating, “… it is my firm conviction that a part of the Yellowstone country should be maintained as a wilderness for the ever-increasing numbers of people who prefer to walk and ride over trails in a region abounding in wild life [sic].” Many who reside in the South Fork area today likely agree that, fortunately, no such road was constructed; thus, preserving the current isolated nature of the upper region of the South Fork Valley.

Through the efforts of Buffalo Bill, the upper South Fork assumed its current land-use status, a region for ranching, hunting, and fishing—not a thoroughfare for tourists traveling to Yellowstone Park with commercial interests providing concessions. Instead, the area became a destination, an idyllic retreat, one that continues to offer visitors and residents a taste of rugged Wyoming as it was at the end of the nineteenth century.

About the author

Dr. Jeremy M. Johnston is now the Center of the West’s Historian, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western American History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody. At the time this series of articles was written, he was also the Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum. His ancestors settled on the South Fork of the Shoshone in the late 1890s near Castle Rock. He received a BA in 1993 and an MA in 1995, both from the University of Wyoming. Then, he taught, history at Northwest College in Powell for more than fifteen years. He earned his doctorate from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, in May 2017. His doctoral dissertation examines the connections between Theodore Roosevelt and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Post 268

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.

![Frederick Courtney Selous, ca. 1910. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. LC-B2-173-11 [P&P]](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=657,height=900,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/PW268_FCSelous-LOC-B217311.jpg)