How Dress Worn in the West Became Western – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2011

How Dress Worn in the West Became Western

By Laurel Wilson, PhD

American western style is known by some familiar materials and details including embossed or fringed leather, silver conchas, and patterns woven in bright earth tones or primary colors. These materials and patterns did not rise spontaneously, but developed over a five-hundred-year-period and included influences from Spain as well as from eastern and western America.

The elements of design that define western style developed from patterns that were found appropriate in particular times rather than adopted willy-nilly. Five main factors shaped what is now described as western clothing: Spanish dress, frontier dress, cowboy dress, Native American design, and changes in technology that were particularly important in rodeo dress.

Spanish Dress

The Virginian, a book about Wyoming cowboys, was portrayed on stage in 1904, Trampas, the villain, was dressed in Spanish-style clothing.

Frontier Dress

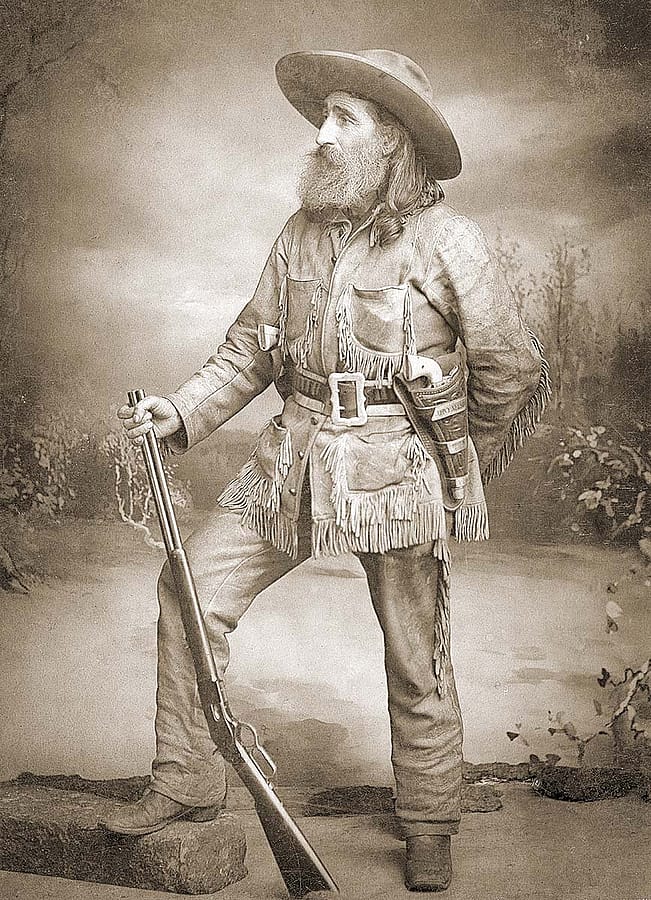

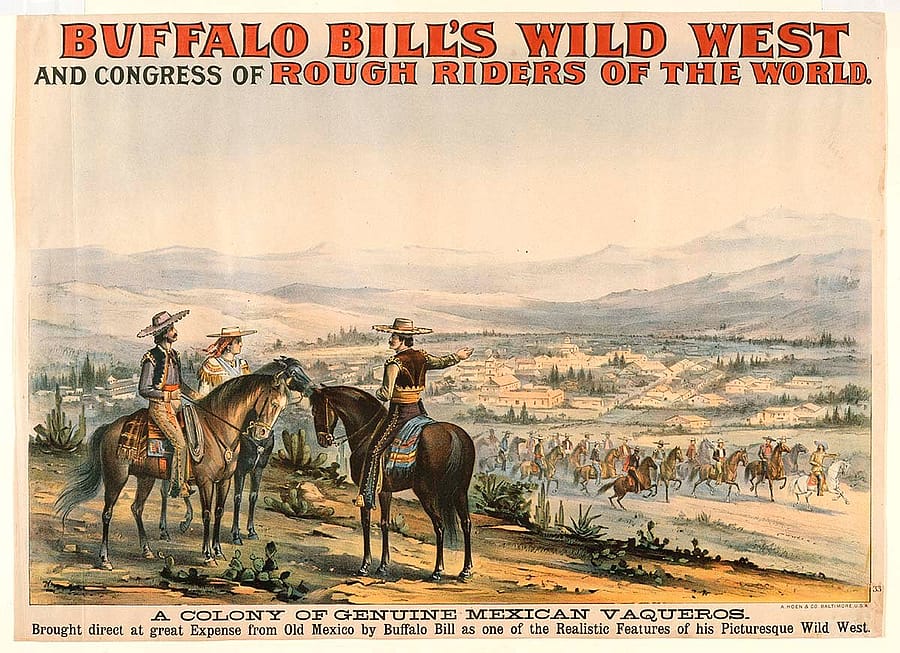

Stereotypical frontier dress with its fringed leather is also an important part of the western design lexicon. Images of Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone usually show them wearing a fringed leather coat and trousers. Fur traders and mountain men found that leather withstood the rigors of frontier life better than cloth apparel. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his cronies wore fringed and fur-trimmed leather as well as broad-brimmed hats when they performed on stage in Ned Buntline dramas in 1873.

Others who adopted fringe were George Armstrong Custer, Theodore Roosevelt whose leather shirt affiliated him with the West during his 1904 Presidential campaign, and Larry Larom, owner of Valley Ranch southwest of Cody, Wyoming, was often pictured in his fringed leather shirt as part of the advertising campaign to lure eastern dudes to the 1930s not-so-wild West.

Cowboy Dress

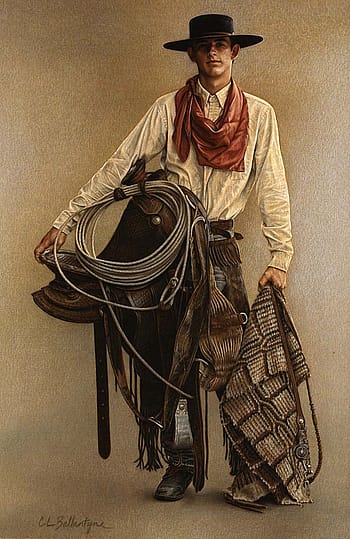

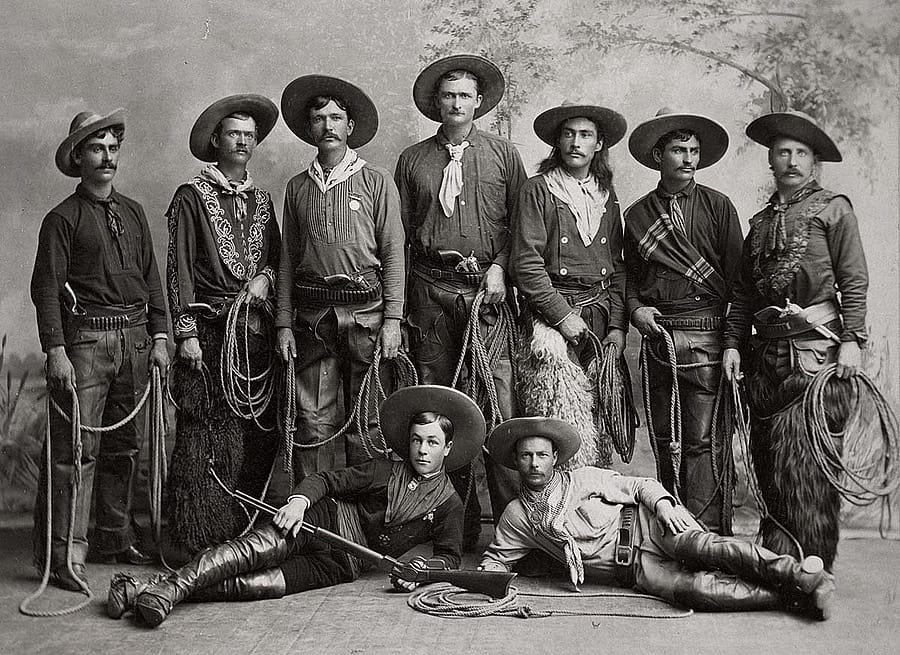

The most important influence on western style, however, is the cowboy. To prove that they had risen to the high rank of cowboy, thousands of still-adolescent boys sent studio portraits to their families back east. In 1878, young Montana cowboy Teddy Blue Abbot summed up what was important about cowboy dress:

I stopped in North Platte, [Nebraska], where they paid us off, bought some new clothes and got [a] picture taken…I had a new white Stetson hat that I paid ten dollars for and new pants that cost twelve dollars, and a good shirt and Lord, I was proud of those clothes! They were the kind of clothes that top hands wore, and I thought that I was dressed just right for the first time in my life.

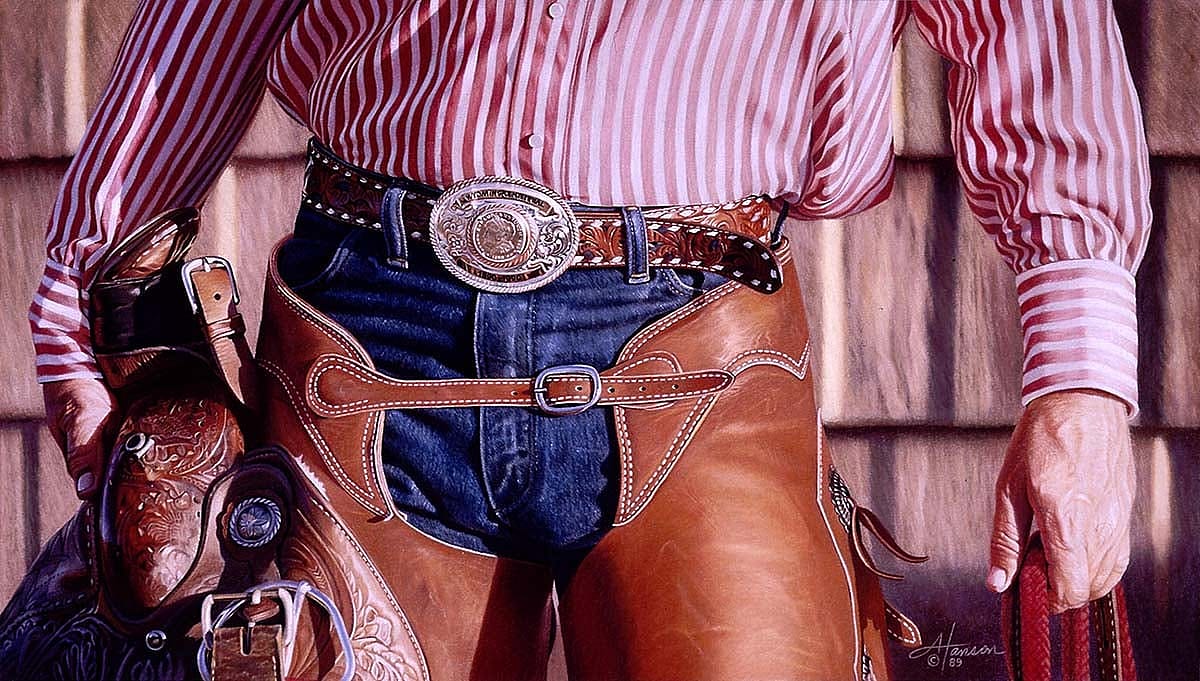

Most cowboy clothing was functional, but even functional dress had some cowboy flair. The most symbolic of cowboy gear were chaps that often had a tooled leather belt and were decorated with fringe and conchas that prevented leather lacing from tearing the somewhat brittle oak-tanned leather. Wooly chaps originated among California vaqueros, but were readily adopted by cowboys riding the range on the cold, windy northern plains.

Stetson hats were familiar all over America, but those worn by cowboys were often distinctive because of the way they shaped the crowns and brims. Western author John Rollinson, writing in Pony Trails in Wyoming, observed that in the 1890s “all wore Stetson hats of the high-crowned pattern—most of which looked like they had seen plenty of service, as indeed they had, for those hats had fanned many an ember into flame for a fire; had served to dip into a creek or water hole to drink from; had been used to spook a horse along side the head, or to slap him down the rump.”

A good fur felt hat was not cheap. Much less expensive hats were available and used until cowboys could afford better quality ones. Frederic Remington’s illustrations showed many cowboys wearing foppy-brimmed hats that were likely made of a cheap quality felt that would not hold shape, especially after suffering the abuse of wind, rain, and snow. Teddy Blue Abbot’s $10 Stetson was an expense that represented one-third to one-half his monthly earnings—a large price to pay for pride.

Cowboys wore a variety of types of pants. According to writer Don Rickey, the most common on the Northern Plains were woolen pants that were intended for dress. They were more comfortable to wear than Levis constructed of stiff denim. Even though woolen trousers were preferred, many cowboys wore cheaper denim trousers. Major William Shepherd, an Englishman who traveled through Montana and Wyoming in 1884, wrote:

On leaving every town some of the boys would appear in a new blue pair of trousers; a large light-colored patch, sewn into the waistband behind, represents a galloping horse as a trade-mark, and informs all concerned that the wearer is clothed in “Wolf & Neuman’s Boss of the Road, with riveted buttons and patent continuous fly…” The patch is left either from idleness or as a memorandum of one’s measurements.

This indicates that denim “overalls,” as they were called, also were commonly worn.

Several of the reminiscences of cowboys say that they wore work shirts made of “hickory” described in an 1894 dry goods dictionary as “a particular style of coarse shirting for its…alleged hickory-like toughness, or superior wearing quality.” Images of cowboys indicate they occasionally wore dress shirts without the starched removable collars that were attached to collar bands with wooden or pearl studs.

Bandanas, also considered important parts of a cowboy’s wardrobe, originated in India. The word “bandana” comes from the East India word “bandhana” which means tie-dyed in intricate patterns. These silken imports were replaced by less expensive printed cotton bandanas still familiar today.

Cowboy boots, said to have been developed in Coffeyville, Kansas, were another distinctive article of dress that marked cowboys in how they looked and also how they walked. Wyoming cowboy John Rollinson remembered his first pair of real cowboy boots.

I never will forget how proud I was when the package was delivered to me. Also, I never will forget how my feet burned and ached while breaking in those calfskin foot coverings. They reached almost to my knee, and had long leather tabs, or pull-on straps, that hung down both sides from the tops. They had a big star, about five inches across, sewed in red and white thread on the boot top. The high heel was hard to get used to, and they gave me an extra inch in height over my former footwear.… Every step hurt my feet, for those boots were a tight fit. I even went without socks and greased my feet, and soon had plenty of blisters. When old man Ross saw me limping, he took action. He filled the boots with oats and poured water into each to wet the oats. That caused them to swell and stretch those boots until they fitted [sic].

Spurs made in a wide variety of styles of plain steel and of silver or with silver inlay have also contributed designs to western style. And, even though firearms are not technically dress, no cowboy would have considered his outfit complete without one.

Native American Dress

Although Native American dress influenced western style and, in fact, strongly affected frontier fringed clothing, Native American designs were not an integral part of the western design lexicon until the twentieth century when Navaho saddle blankets began appearing in catalogs such as the 1910 J.H. Wilson Saddlery Company, the 1912 Herman H. Heiser, and the 1914 R.T. Frazier’s Saddlery. Even the Charles Shipley Saddlery and Mercantile of Kansas City, Missouri, showed Navaho saddle blankets, rugs, and swastika spurs in its 1914 catalog. In the nineteenth-century, Indians were portrayed as ruthless savages, and during the early twentieth century, there were warlike depictions of Indians painted by the same artists who would also produce more peaceful scenes.

By the 1910s, Indian troubles had ended, at least for white settlers, and artists tended to picture a romantic “noble savage” occupying glorious landscapes. This fascination with Native Americans did not end with artists. Among those who interacted with Indians were the would-be cowboys that visited western dude ranches. During the 1920s and 1930s, Larry Larom of Valley Ranch near Cody, Wyoming, had natives from the Crow tribe meet dudes returning from trail rides. The Indians, wearing traditional breechclouts over long underwear, then performed dances for the ranch guests. Larom, as well as most dude ranchers, sold “Indian curios” such as rugs, jewelry, leather clothing, and beadwork at his dude ranch.

In the golden era of dude ranching during the 1930s and 1940s, when wealthy easterners were no longer traveling to Europe because of the Nazi threat, the entire Rocky Mountain region filled with dude ranches. The most popular northern ranches were located in Montana and Wyoming near Yellowstone National Park. The area around Wickenburg, Arizona, was the southern center of dude ranching. Eastern dudes spent between six weeks to two months at northern ranches during the comfortable summer months and about the same amount of time at southern ranches during the winter. This led to a mixture of northern and southern Indian arts making their way into the western design lexicon.

Technology

Rodeo and two important changes in technology—the use of metal embellishments and chrome tanning—affected the appearance of western design. By 1900, nickel and silver “spots” for protecting and embellishing leather gear were available because of the manufacturing revolution of the late nineteenth century. It was possible to insert so many spots without damaging the leather because chrome tanning, developed by 1900, made leather more elastic and less brittle than oak-tanned leather commonly used for cowboy gear.

Catalog copy in the 1915 Shipley catalog clearly illustrates how a change in tanning technique and the ability to insert spots easily could influence style. The entry says, “Made from our special green cast lace leather, which does not get hard and wears as well as any Chap leather made: full buck-sewed; has 3 gross of nickel spots and 14 solid nickel conchas; flower-stamped Belt.”

Soon, rodeo cowboys were decked out in thoroughly spotted chaps, and now in the twenty-first century, rodeo chaps are embellished with mylar to provide similar flash to wildly bouncing chaps. Another important element of rodeo dress is the trophy buckle that first appeared on a bucking belt from Glendive, Montana. By the 1920s, trophy buckles were an integral part of rodeo champion dress. Now, any self-respecting rodeo cowboy has a whole collection.

Western fashion grew from the most important groups that lived and worked in the American West. These were the Spanish, frontiersman, cowboys, Native Americans, and the rodeo, all contributing designs that have become part of the American western design lexicon.

About the author

Dr. Laurel Wilson is Professor for the Department of Textiles and Apparel Management at the University of Missouri at Columbia where she is also curator of the Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection. She curated the special exhibition Dressed Just Right: An Evolution of Western Style from Function to Flamboyance, which was on view at the Center of the West in 2011 and 2012.

Post 275

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.