Nate Salsbury’s Black America, Part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2018

Nate Salsbury’s Black America: Its Origins and Programs

Part 1

By Sandra K. Sagala

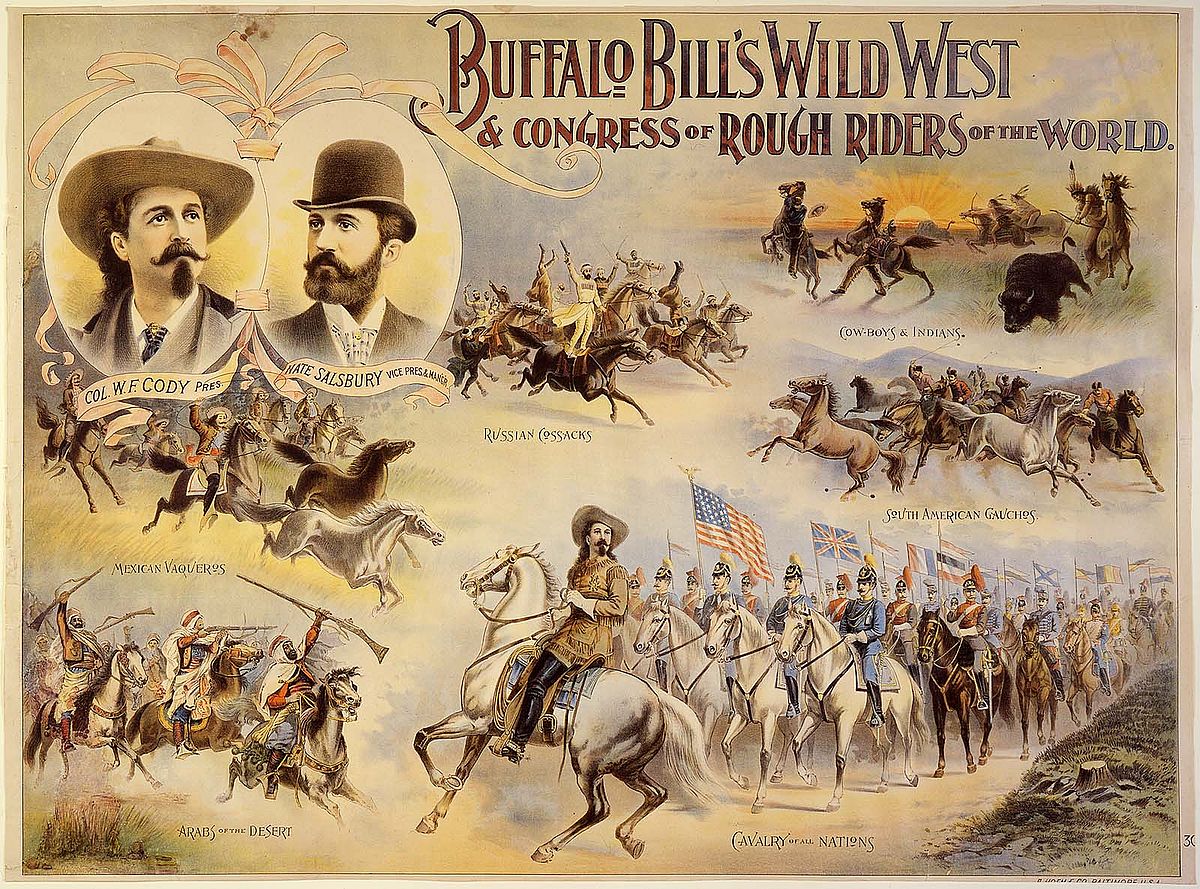

In spring 1895, Nate Salsbury (1846–1902) and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846–1917), partners in the Wild West extravaganza, masterminded an extraordinary new entertainment featuring hundreds of theatrical and musical performers, imaginative scenery, and educational historic programming that rivaled the western exhibition.

Salsbury applied his experience—gained from molding the Wild West into one of the era’s most popular outdoor attractions—to showcase pre-Civil War lives of negroes. He called the new program Black America. Just as the Wild West depicted a rapidly disappearing frontier, Black America would represent the bygone antebellum era. Northerners were acquainted with the period only through published accounts of slavery and plantation life they read, or by hearing “garbled stories” of life south of the Mason-Dixon line.

How then, did Salsbury, a white soldier-turned actor, become a purveyor of negro culture, history, and music?

Who was Nate Salsbury?

Born in Freeport, Illinois, in 1846, Salsbury joined the Union Army at the outbreak of the Civil War. His youthful singing and dancing relieved the tedium of army life and, together with his vibrant personality, made him renowned beyond his unit. One day after his commanding officer heard him sing, he allegedly remarked: “If I had a regiment of 1,000 men like Salsbury, I could lick 3,000 rebels.” How music, even coming from the talented Salsbury, could overcome enemy fire was evidently not questioned.

Salsbury served in Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas; was captured at Andersonville; and was thrice wounded but reenlisted as soon as he was fit. When he was mustered out with $20,000 won from fellow soldiers in poker games, he started business college. He later withdrew when he ran out of money, and then became interested in amateur theatrics.

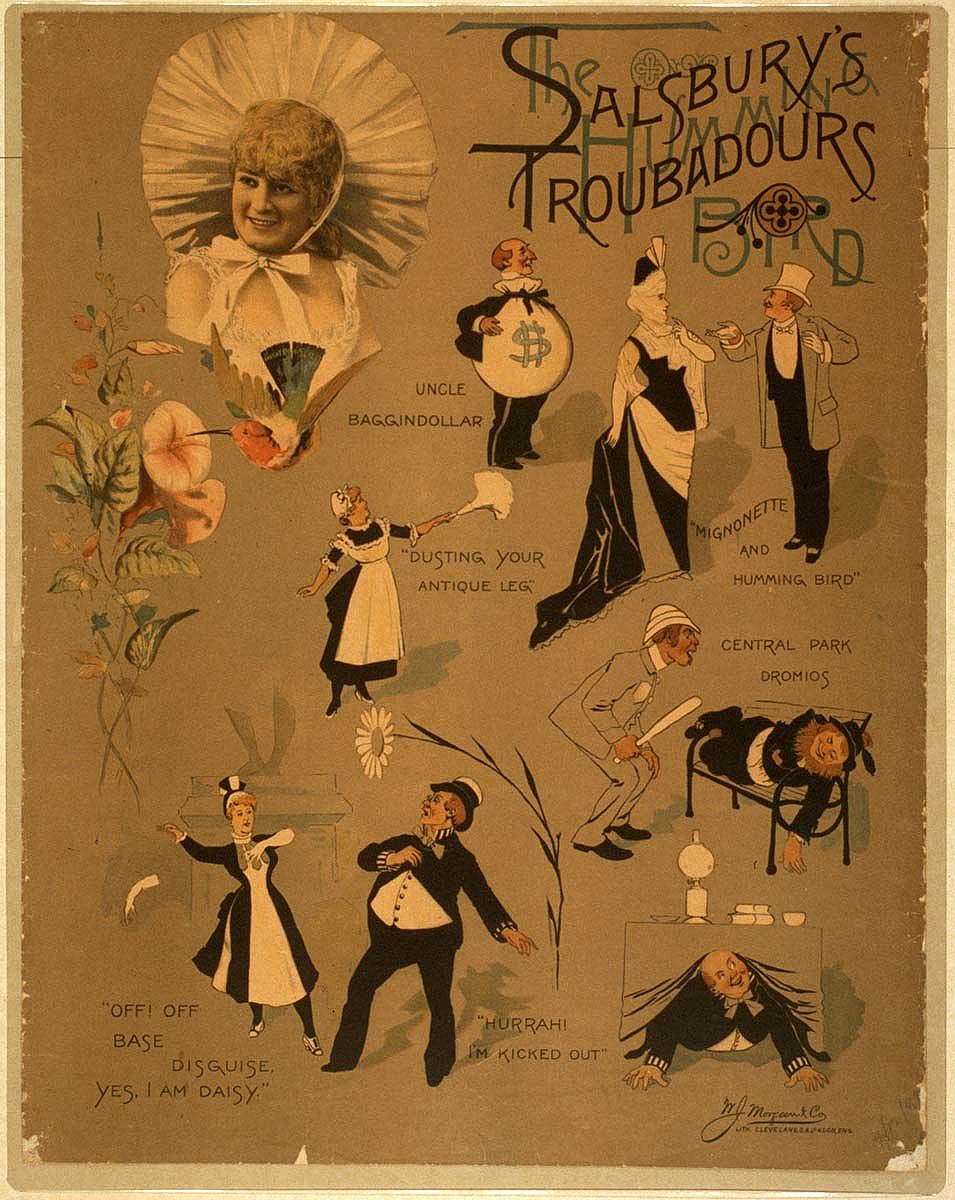

Having no stage experience, Salsbury nevertheless applied for a place in a dramatic company. In his first performance with a Grand Rapids, Michigan, stock company, he had one line in John Brougham’s Pocahontas. In 1869, he entered the Boston Museum Company; four years later, he joined Hooley’s Comedy Company in Chicago, where he became popular as an eccentric comedian. Not content with simply performing, Salsbury hatched a plan to make a business out of his interest. He convinced fellow actor John Webster that they should pool their salaries to start their own stock company. Salsbury’s Troubadours, as the troupe was named, toured the United States and Europe for more than ten years, performing farce comedies that Salsbury wrote, including Patchwork; On the Trail, or, Money and Misery; and The Brook, “and made a very great deal of money.”

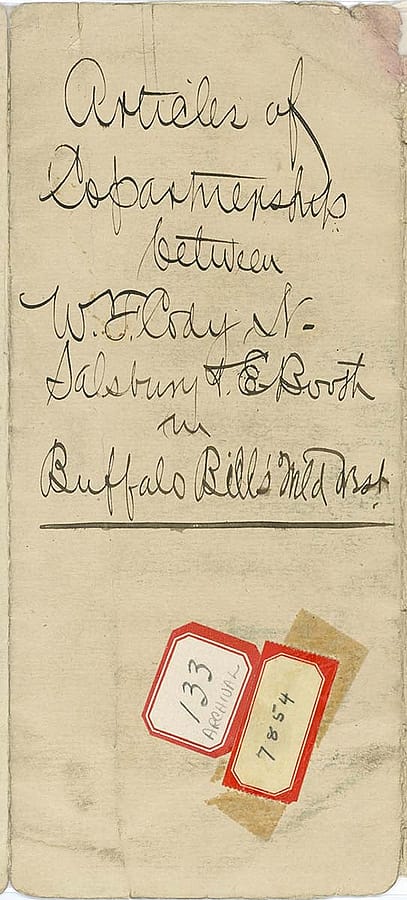

Partnering with Cody in the Wild West

By 1882, Cody had also been touring the country for ten years. He acted onstage in frontier melodramas in his own Buffalo Bill Combination when Salsbury contacted him with a business proposition. They met in Brooklyn, New York, while Cody’s dramatic troupe was performing at the Grand Opera House, and Salsbury’s company was performing at the Park Theater. Introduced to Australian horse races while touring with the Troubadours, Salsbury had been inspired to develop a horsemanship show. He envisioned Cody as the central figure and proposed the concept to him:

Nobody’s ever done it before. It’s the greatest show idea yet. We’ll tell the story of the West with cowboys, Indians, buffalo, and bucking horses, not on the stage of a theater but in the outdoors. It will be like a circus yet not a circus. It will be lifelike and true in every detail.

Cody thought it a good idea. His melodramas had outgrown the constraints of a stage with an ever-expanding cast that included real Indians and live animals. When Salsbury predicted there was a million dollars to be made if he managed the show and Cody headed the bill, the two struck a deal. Their scheme didn’t get off the ground immediately, however. Salsbury’s plan included eventually taking the new program to Europe, so that summer he toured the continent to get a feel for a country “where all [the show’s] elements would be absolutely novel.”

Salsbury concluded that neither he nor Cody had enough money to do the grand show properly, so they agreed to wait a year; besides, the Troubadours still had bookings to fulfill. Cody nevertheless took Salsbury’s idea of moving his performances to outdoor venues and partnered with William “Doc” Carver, a dentist-turned-shooter, to make it happen. When Salsbury learned of Cody’s betrayal and his choice of partner—Salsbury despised Carver—he predicted the pair’s venture would fail, but still believed the idea could be profitable if it were properly handled. After one contentious season, Cody and Carver split, and Salsbury reinstated his partnership with Cody, creating Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Too soon, Salsbury discovered problematic tendencies of his business partner. Once, after he found Cody “boiling drunk,” he considered bailing out of their agreement. He admitted years later, “If I had done so, I would not have had as much money as I made out of the Show afterwards, but I would have had infinite peace of mind, which I have never had since.” Despite reservations, Salsbury remained convinced they had a winner on their hands and so began a sixteen-year affiliation. With Cody vowing to remain sober, and Salsbury providing watchful guidance, the next Wild West seasons proved successful.

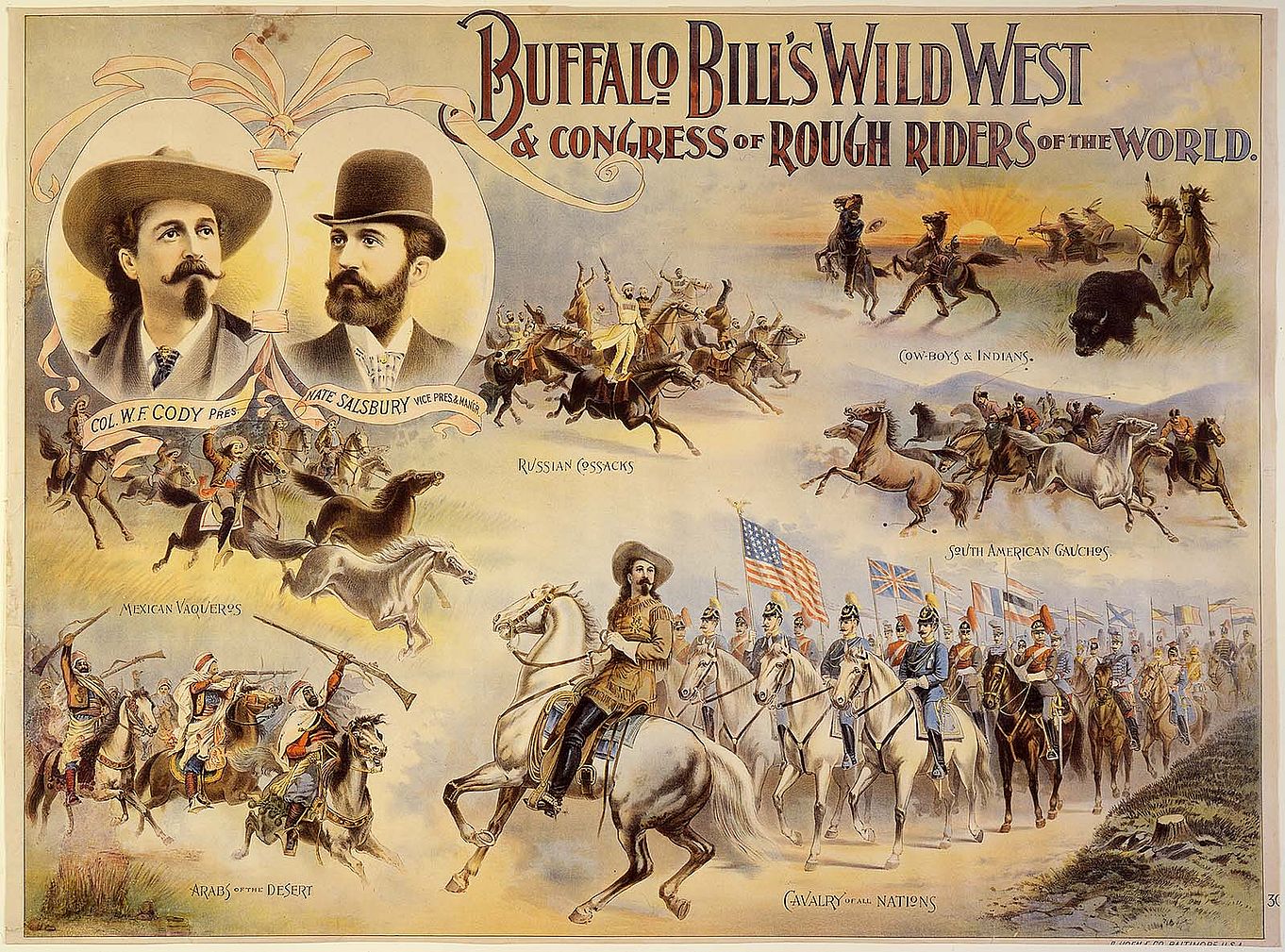

Enter the Rough Riders

By 1891, to broaden the scope of the Wild West and to encourage return audiences, Salsbury introduced a new feature titled “Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” The exhibit featured skilled horsemen from Europe and South America; Sioux Indians; U.S. soldiers, including black “buffalo soldiers” so named for their hair thought to resemble buffalo hide; and cowboys. Ads promised the audience “all kinds, all colors, all tongues, all men fraternally mixing in the picturesque racial camp.”

In his book Slavery on Stage: Black Stereotypes and Opportunities in Nate Salsbury’s “Black America” Show, biographer David Fiske observes that it seemed Salsbury believed that understanding “diverse cultures would lead to a better brotherhood of mankind.” Whether the disparate troupe contributed to the dispelling of racial prejudices is unknown, but, as Fiske notes, it “suggest[s] that Salsbury believed in the marketability if not the actuality, of such sentiments.”

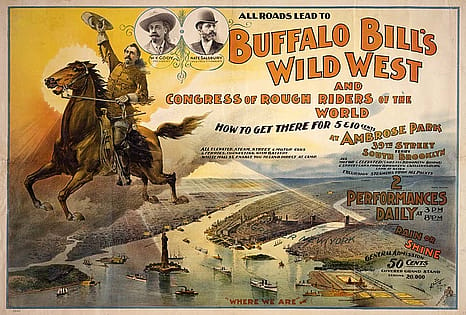

The Wild West earned both Cody and Salsbury a nice salary, especially after a highly successful 1893 season in Chicago which took advantage of audiences swelled by the World’s Columbian Exposition. But their finances were far from stable. Planning on a stationary season at Brooklyn’s Ambrose Park for the 1894 summer, they erected a covered grandstand with 20,000 seats. Despite the Park’s accessibility by ferry, attendance was sparse. Cody’s penchant for indulging in dubious business enterprises and the public’s capriciousness toward frontier-themed entertainment also caused the Wild West to bleed money. In a letter to his sister, Cody wrote, “I am too worried just now to think of anything…my expenses are $4000 aday [sic], and I can’t reduce them, without closeing [sic] entirely…this is the tightest squeeze of my life.”

Salsbury attempted to redress the losses by recommending that the Wild West return to its original itinerant arrangement, moving to a different city with an untapped audience every day. Because the Park’s forty acres was an excellent showground, it was unreasonable to allow it to remain idle when the show was on tour. Accordingly, Salsbury began arranging for an Italian industrial exhibit to take its place, but he had to abandon the project when he became ill and unable to attend to details. Heedless of Salsbury’s poor health, Cody entreated him in a letter of January 1895:

Dear Nate,

Its [sic] wrong to trouble you. But I am in a tight place. And if I had a little time to go on I am sure that I could pull through and make a loan on my property…I can tide over with $5,000 do you think the bank of the Metropolis would loan me $5,000 for four months…Nate this is to keep my credit good that I ask this…give me your advice, and tell me how to pull out of this hole. Bill

Staging Black America

Theories abound as to how or why Black America came to be. Cody’s plea for funds may have enticed Salsbury off his sickbed to develop an exhibit that would generate badly needed income. Wild West audiences had displayed an appetite for demonstrations of other cultures; for this reason, Salsbury and Cody toured the show in eastern and southern states, far from its western roots.

Two years previously, ethnic villages displayed the customs, dress, and talents of various countries at the World’s Fair. This may have prompted Salsbury to consider featuring the American South which, for metropolitan Easterners, would be as culturally exotic as foreign lands or the Frontier West. When a reporter asked how he envisioned a show in which five hundred negroes would sing, dance, and perform in tableaux inspired by the pre-Civil War South, Salsbury said he had two motives: to give a performance of ethnological value, and because “I wanted something that should be purely national in color and a novelty.”

Another report had Salsbury mingling with other showmen in New York’s Actors’ Club and mentioning his idea for an all-colored musical program. According to Harry Tarleton, who would become the show’s stage manager, “[t]he other men said it could not be done, and Nate Salsbury said, ‘I will show you fellows it can.'” To a journalist, Salsbury later related:

The idea came to him some years ago when he was making a tour of the southern states. Having familiarized himself during the war with the colored race, he saw, during this journey, that a certain phase in American life was rapidly disappearing, and then came to him the thought that to present an entertainment showing this life in its many phases before it had become eradicated would be an instructive creation and one in which northern people would take great interest.

In his book 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business (1954), veteran showman Tom Fletcher attributed the show’s genesis not to Salsbury at all, but to Billy McClain, a black comedian and musician. The previous year, McClain had produced a theatrical program titled The South Before the War, and he initially contacted Salsbury to find employment for his company during the summer. Salsbury recognized McClain’s superior connections and rapport with well-known names in minstrelsy. Possibly due to his illness, Salsbury considered producing and financing the show, leaving McClain to direct and manage the program.

![Billy McClain, between February 1901 and December 1903. C.M. Bell Studio Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. LC-B5- 51215B [P&P]](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=400,height=508,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PW281_LC-BS-51215B.jpg)

Historically, negro minstrel shows focused on themes of plantation life in bondage, but Salsbury often reiterated that Black America would not be a minstrel show. “It is not a ‘show’ at all; it is an exhibition.” It would differ from minstrelsy in that the cast was composed, not of whites in “burnt-cork caricatures,” but solely of black performers considered to be portraying their everyday lives. Salsbury said, “My purpose in gathering together the very best I could possibly obtain from amongst the black race of America was to show the people of the North the better side of the colored man and woman of the South.”

Salsbury cannily understood that the depravity and torturous treatment of slaves needed to be downplayed to appeal to an audience. In this, Salsbury replicated the Wild West’s intentional exclusion of similar negative depictions of white’s poor treatment of Indians. Instead of addressing issues of slavery, the performances were “indicative of the untrammeled outdoor life that they have lived” and the “easy-going methods of enjoying life that, prior to the war, under kind masters, it was the fortune of slaves to enjoy.”

While Salsbury’s name is most associated with Black America, Cody was a relatively silent, but very invested, partner. In March 1895, the Kearney (Nebraska) Hub reported:

Not content…with his laurels, won with his great exhibition and delineation of the old frontier life, Mr. Cody has planned another great original enterprise of as great, if not greater, magnitude than the first…a grand exposition of the history of American slavery.

Mr. Cody said[,] “Negro humor and melody will in this show reach the acme of perfection, as we have engaged a large company of the most celebrated colored opera and jubilee singers and each and every member of the aggregation will possess musical talents, so that the grand chorus of one thousand voices will be a thrilling performance.”

His comments indicate that Cody expected Black America to consist of the colossal number of a thousand performers. His wish for a program bigger and better than even the Wild West meant that Salsbury, nearly an invalid, would be managing four hundred more people than were eventually numbered among the cast.

Cody’s brother-in-law Hugh Wetmore, editor of the Duluth Press, also expounded on the innovative idea:

[A]nother strictly ‘American institution’ [is] passing into oblivion and the same creative mind that placed the wild western life in the midst of civilization aided by his partner, Mr. Nate Salsbury, also determined that ‘Plantation Days in Dixie’ in the antebellum era should be seen as it really was by the present generation, before the last of those who lived in ‘Slavery Days’ should pass away to be seen no more.

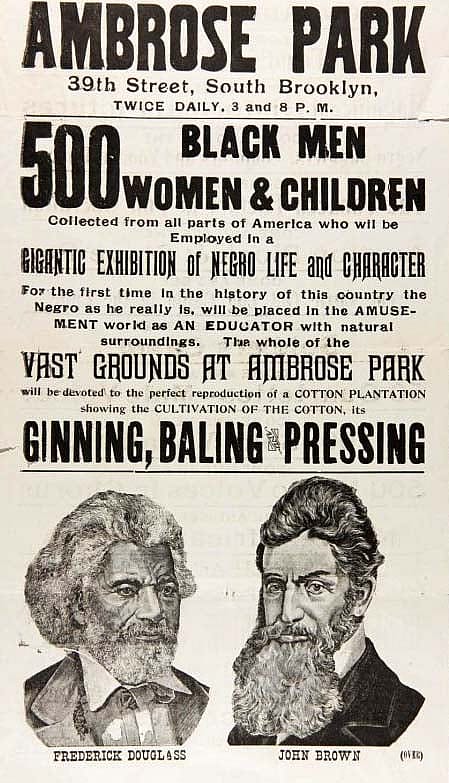

Black America opened on May 25, 1895, and played in Brooklyn’s Ambrose Park arena twice daily for seven weeks. Advance publicity in the New York newspapers promised a:

Typical Plantation Village of 150 Cabins, 500 Southern Colored People, presenting Home Life, Folk Lore, Pastimes of Dixie; More Music, Mirth, Merriment for the Masses; More Fun, Jollity, Humor, and Character presented in Marvelously Massive Lyric Magnitude for the Millions than since the days of Cleopatra.

[See] the Afro-American in all his phases from the simplicity of the Southern field hand to his evolution as the Northern aspirant for professional honors and his martial ambition as a soldier, a profession in which he has acquired an enviable record.

According to one publicity poster, Black America would display:

- The Negro as a soldier (Best drilled Cavalry company in the US)

- The Negro as a Musician (Capitol Band of Washington)

- The Negro as a Vocalist (250 Negro voices in concert)

- The Negro as a Dancer (100 Buck and Wing dancers)

- The Negro as an Athlete (75 Athletic marvels)

- The Negro as a Horseman (the whirlwind Hurdle Races)

- The Negro as an Actor (reproduction of Life in Africa)

In the next installment of Points West Online, learn about the staging, music, specialty acts, and all the performances of Nate Salsbury’s Black America.

About the author

Sandy Sagala is currently a member of the Papers of William F. Cody Editorial Consultative Board and has contributed several stories to Points West. She has also authored four books on William F. Cody, including Buffalo Bill on Stage and Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen. In spring 2019, University of Kansas Press published Buffalo Bill Cody, A Man of the West, written by Prentiss Ingraham and edited and introduced by Sandra Sagala.

Post 281

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.