Nate Salsbury’s Black America, Part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2019

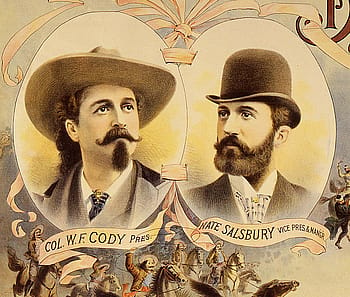

Nate Salsbury’s Black America: Its Origins and Programs

Part 2

By Sandra K. Sagala

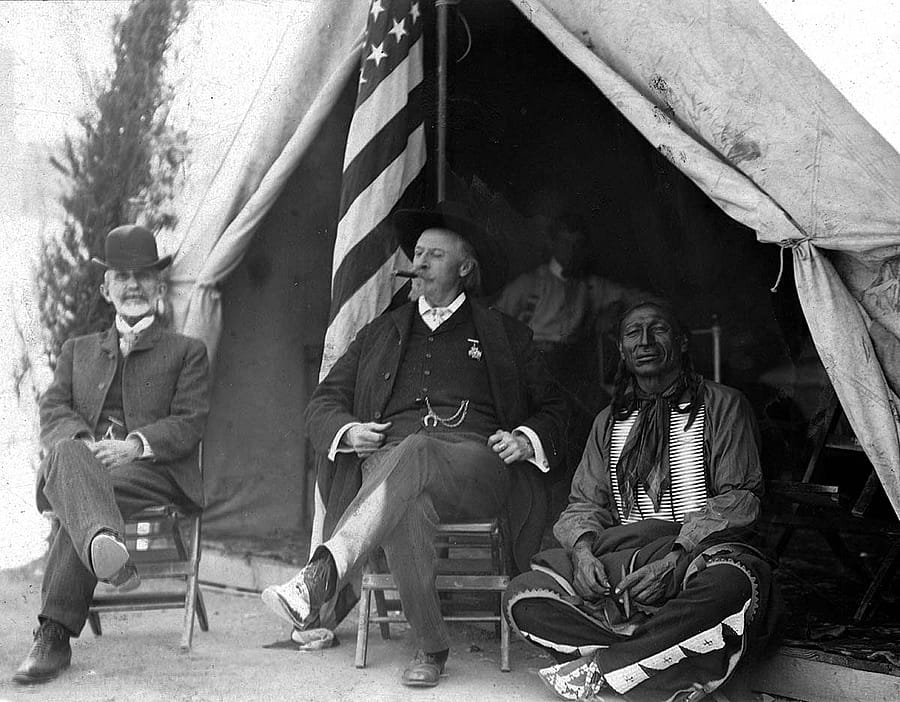

In the previous issue of Points West, Sandra Sagala introduced readers to Nate Salsbury’s Black America, a June 1895 attraction focused on the pre-Civil War lives of negroes. As a partner in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Salsbury used his Wild West know-how to launch an experience that represented the bygone antebellum era. Using a host of newspaper accounts of the day, Sagala continues the story below.

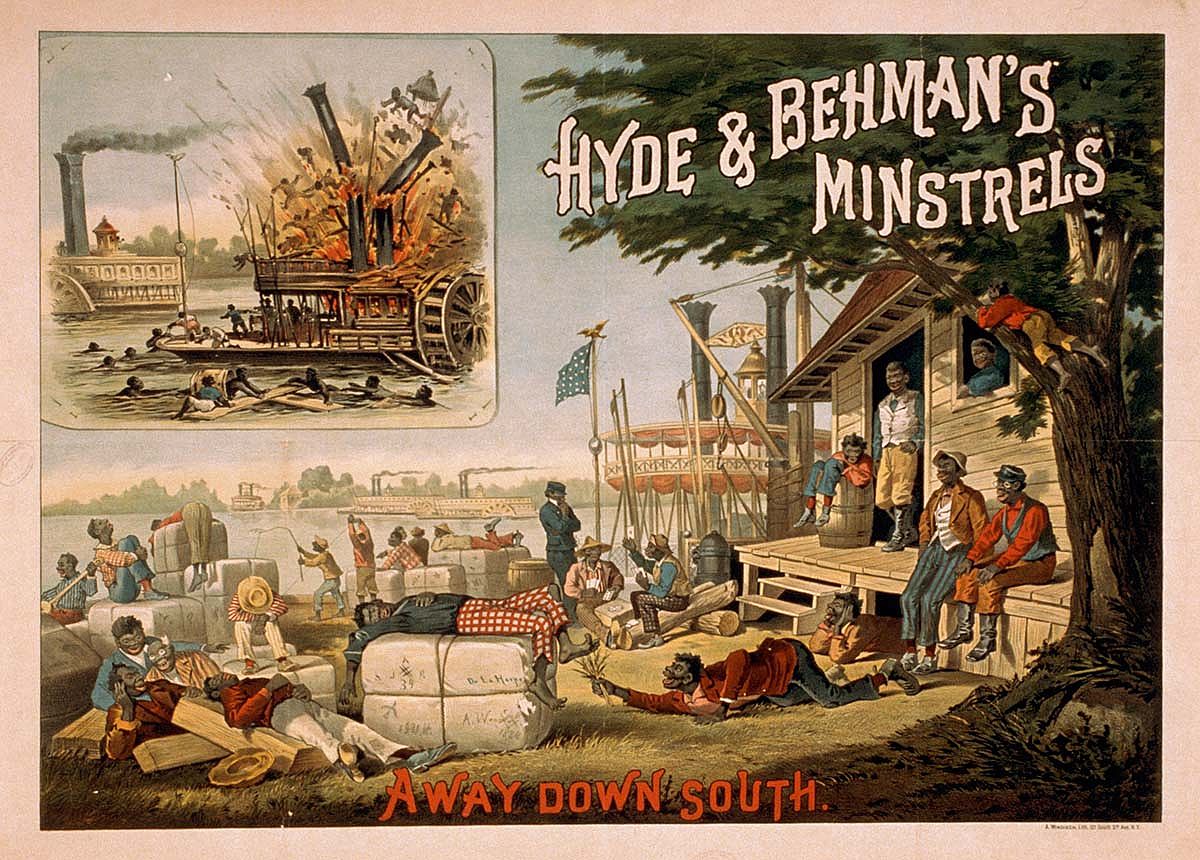

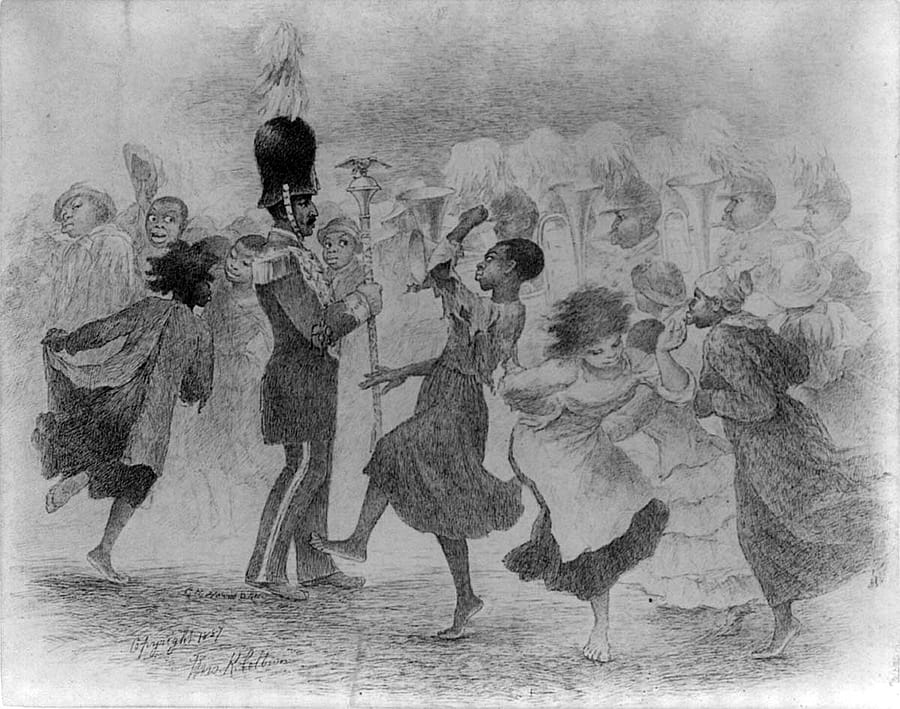

Hyde & Behman’s Minstrels, 1884. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 US.A LC-USZ62-26099

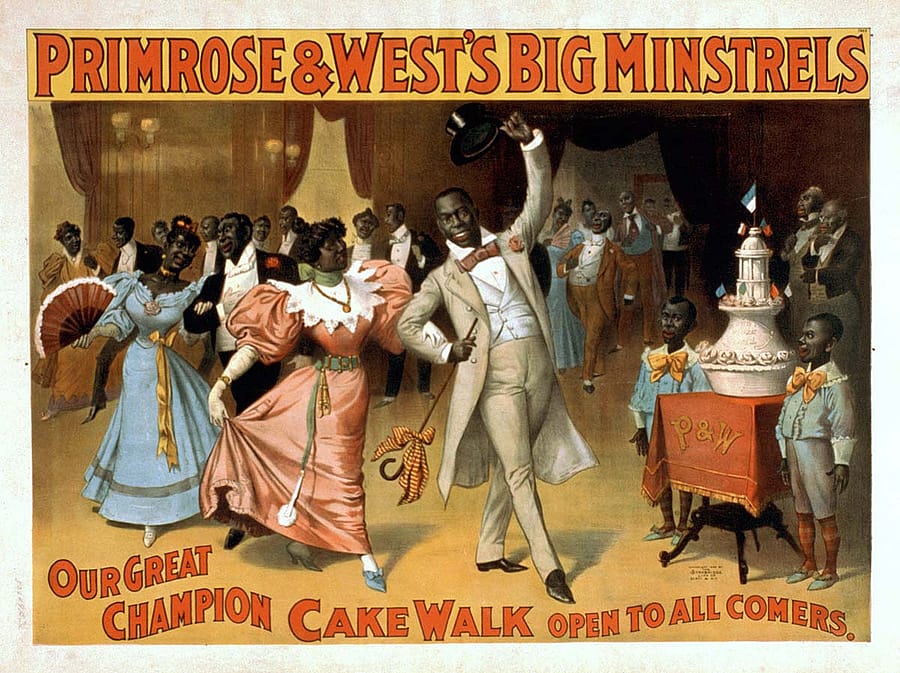

Primrose & West’s Big Minstrels, ca. 1896, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA. LC-USZ62-24635

Primrose & West’s Big Minstrels always up to date, ca. 1895. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA. LC-USZ62-24637

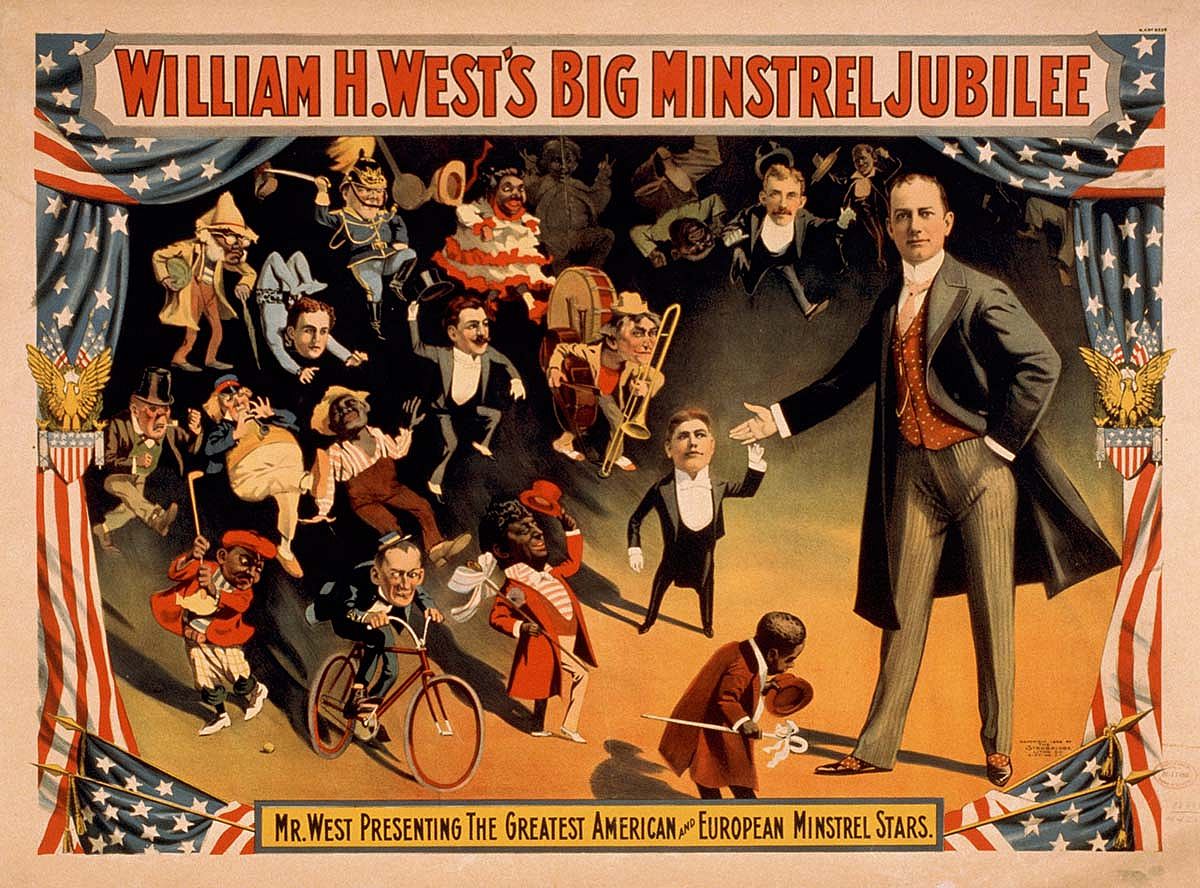

William H. West’s Big Minstrel Jubilee, 1899. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA. LC-USZ62-24131

Strolling the Black America grounds

At the [Black America] gate in Ambrose Park, Brooklyn, New York, visitors paid 25¢ for general admission or 50¢, 75¢, or $1 for increasingly desirable reserved seats. Before the more traditional “theatrical” performances began, organizers encouraged audiences to stroll the grounds to witness how Southern life was lived “befoh’ de wah.” A black village from a southern plantation had been reproduced, and visitors could watch the black performers “keeping house” in 150 log cabins that also served as their accommodations.

Salsbury also had an acre of cotton planted so visitors could observe how it was harvested and pressed into bales. As they worked, the negroes sang about their happy life, “the contented, lack-of-thought-for-themorrow sort of life.” The bales were then disassembled and readied for the next performance.

The stage itself measured 120 by 134 feet, large enough to hold 620 musicians and singers. The backdrop, painted by a Boston artist, featured mountains sloping down to green fields and a steamboat moored at a river’s wharf. The right side depicted a plantation’s residence with the musicians positioned to appear as if they were on the veranda.

Let the show begin

The program began with singers promenading into place from both sides of the field—women from one side, men from the other—to the music of the stage band. When all were in position, show manager Billy McClain, in a dress suit and tall hat, mounted a pedestal to conduct the 500-strong chorus…. Whatever visitors had anticipated in an all-negro show, they were undoubtedly surprised and startled at the sights and sounds. One reviewer remarked:

The negro is a natural musician, and there is no sweeter or prettier music than that from the negro’s throat. The singing of these black people invites curious attention, not only from its wonderful precision, marvelous vitality and unique quality of tone, but because of the demonstration of the potency of what might be called naturalism.

Following the extensive selection of popular songs, specialty acts stereotypifying black culture commenced. According to the contemporary press, while the chorus sang “Watermelon Smiling on the Vine,” an old, white-haired black man rode onstage in a two-wheeled cart heaped with watermelons and pulled by a donkey. A mad scramble ensued as all the members tried to grab a melon, while the audience reveled in the hilarity.

A cakewalk—the most popular act on the program—ended the first part. The dance originated in slave celebrations when the work week was finished. At first, only men participated in the high-stepping dance, often dressing in hand-me-down finery, mocking their masters’ dress and lifestyle. When women were allowed to join in, couples competed with graceful or grotesque struts in hopes of winning the cake, the best prize plantation slaves had to offer. In Black America, twenty or thirty couples, costumed in their gaudiest outfits, paraded around the arena in hopes of winning the audience’s favor.

The second part opened with specialty acts, such as acrobat Charles Johnson, juggler James Wilson, and soloist Madame Flower. Contortionist Pablo Diaz, “the creole corkscrew,” then “showed what remarkable twistings can be accomplished by the human form.” These were followed by “barrel boxing” in which two men, each standing in a barrel, tried to knock over the other.

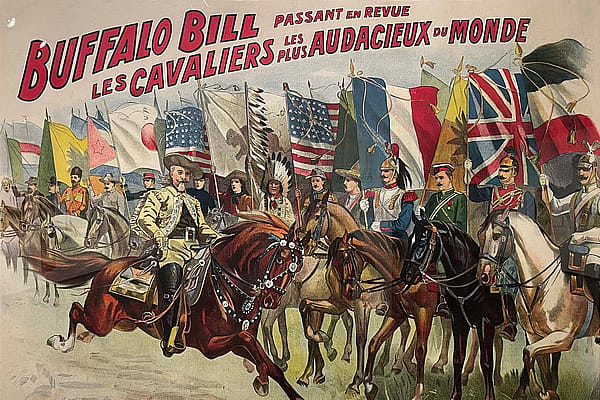

With the Wild West, Cody and Salsbury were greatly concerned with the authenticity of anything or anybody connected with the show, and Salsbury insisted on that same standard for Black America as well. No white men or northern negroes appeared in the program. He told one reporter, “The negro of the north has become a different being from his brother in the south, and hence all our performers have been brought direct from the southern states. There is not a northern darky to be found among the whole three hundred.”

Consequently, Salsbury sourced the twenty soldiers of the Ninth Cavalry from a unit on furlough from the regular army. In full uniform, they performed precise military maneuvers and exhibitions of riding and sabre exercises. The press reported:

It is rather an impressive and suggestive sight to see these men who a few years ago were regarded as mere property arrayed in the livery of the country whose martyred President struck the shackles from their limbs. These men are all giants in Stature, fine looking fellows, and the gaudy cavalry yellow present[s] a striking and picturesque line to the spectator.

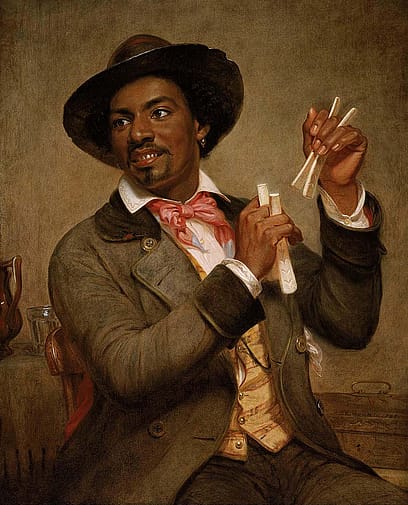

The program continued with a host of banjoists and two dozen players who clacked the “bones”—a folk instrument shaped like ribs which, when knocked together, produced a rhythmic percussive sound—that brought out the “plantation hands.” They engaged in “buck and wing” dancing, resembling modern tap dancing, that opened with performers in a circle being encouraged to stomp and hop in time to the beat. The irresistible music had the audience clapping along, urging the dancers on to faster and faster rhythms.

The Grand Finale commemorated the prominent place slavery had held in America’s history, and one that had been ended by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation barely thirty years earlier. The chorus paid tribute to abolitionists and Union generals as their images appeared on canvas. To close, they sang “America,” and the chorus saluted a representation of Lincoln and made their final bow.

Running the operation

Salsbury and McClain soon discovered that Black America’s musical numbers were the most popular. Within only a few weeks, all the specialty performers had been let go with full salary. Jugglers, jockeys, and foot racers were eliminated in a concerted effort for improvement, i.e. more musical acts. As one newspaper raved, “The singing is really the greatest and most impressive feature…. It is the singing more than anything else which everyone leaves the grounds talking about.”

Stage Manager Harry Tarleton recalled Salsbury as “a very particular man in the way acts should be shown, clean cut and every act finished…. His shows never had any objectional [sic] features, but were

educational always and always clean.”

“There was no acting,” wrote one reviewer. While there was a general program, “they never sing nor dance nor go through their Jim Crow antics the same way two nights in succession.” Although slavery had been abolished years earlier, prevalent early nineteenth-century prejudices persisted. Thus, the contemporary press, meaning to be complimentary, found that:

It is a common remark of theatrical men that the negro is funny only when he isn’t trying to be…. He does what seems to him the most natural thing to do, and the result is that about everything he does is funny.

Just as the Wild West’s cowboys and Indians were contracted to a certain number of performances, they also promised to “keep themselves and [their] gear clean, conduct themselves in orderly manner, no fighting, drinking, gambling.” Cast members of Black America were held to the same requirements. Salsbury claimed that any performer “attempting affectation will be instantly discharged,” but he felt he had no need to discipline.

Touring Black America

Reviews appear to indicate that Black America was extremely popular. But despite good press and attendance counted in thousands, Salsbury felt hopeless and was ready to close the exhibit after only three weeks. The negativity may have been due to his ongoing health concerns—he had had a “severe surgical operation” in mid-June—or to his feeling that the enterprise was ahead of its time. In an interview, Salsbury suspected that the show had only limited appeal. The public, he intimated, was not yet ready for an all-black exhibit, that there seemed to be a popular impression that this kind of performance was suitable only to the taste of poorer classes.

The New York Times noted that black Northerners had little in common with the negro of the South who was more interesting, simply because “characteristics of slavery days still clung to him.” Thus, Salsbury believed it was advantageous for Northerners to see the “bright side of the slave’s existence” with their “peculiarities” and “good traits,” perhaps in counterpoint to persistent racial prejudices.

When Cody argued that the show should continue, Salsbury did carry on despite his qualms. Once he overcame his reservations, Salsbury’s instinct to keep the show at Ambrose Park—despite a scheduled opening in Boston in mid-July—substantiates the show’s success. He offered the Boston venue $10,000 to postpone the date, but the offer was refused.

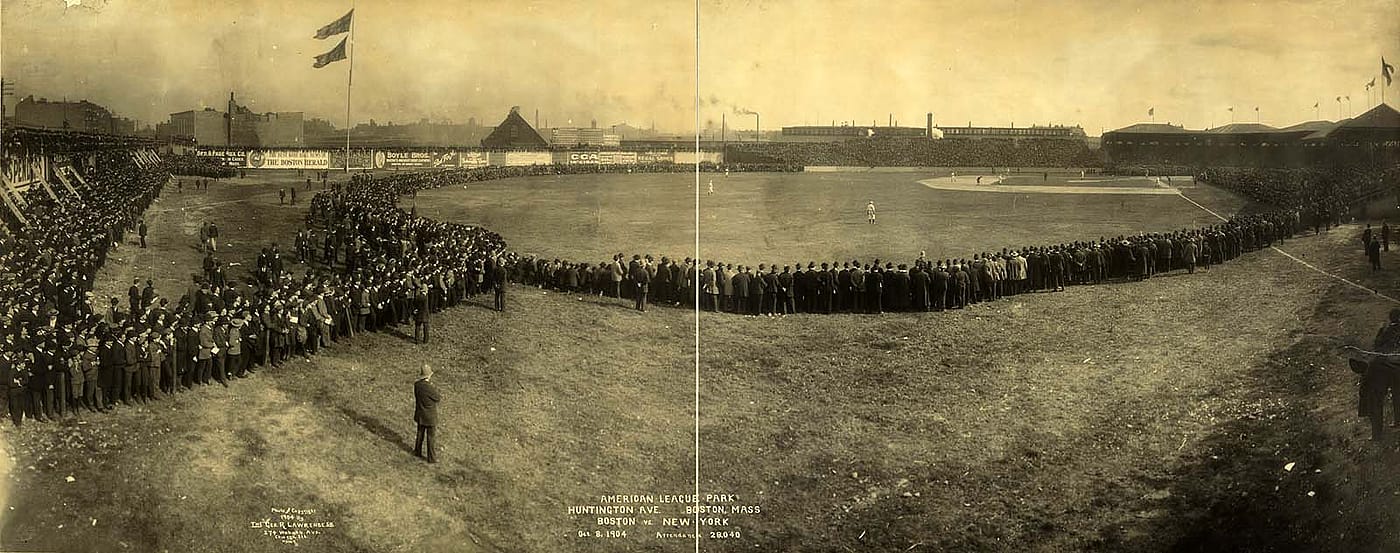

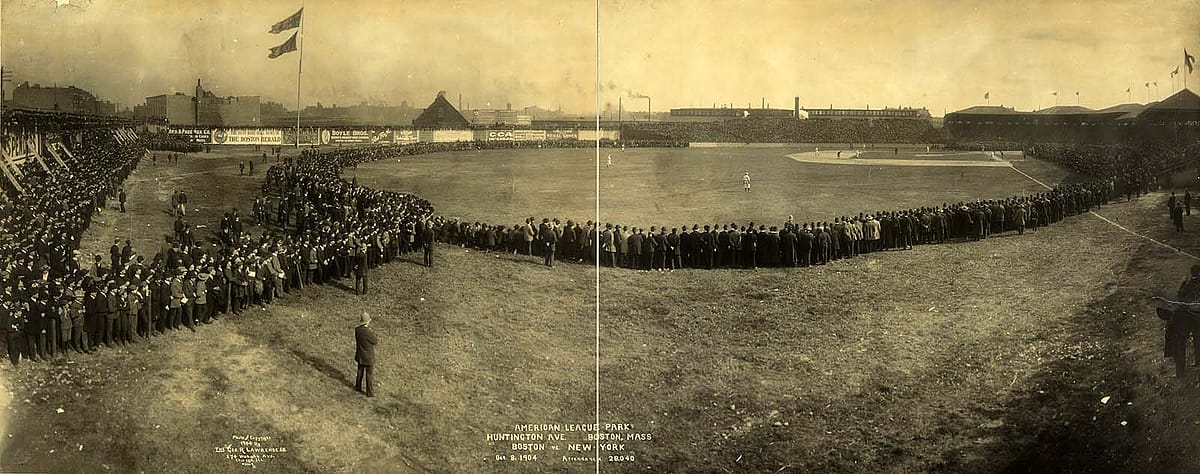

On July 13, 1895, Black America concluded its Brooklyn engagement, and the entire company (except the McClains who had moved on to participate in Suwanee River, a similar production) boarded a chartered steamer that would ferry the 587 performers, 150 cabins, cotton baler, and scenery to Boston. A grandstand seating 7,500 persons had been built at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. Shortly after the first performance, it was obvious that this was an entertainment that fulfilled every promise, being one of the most weird, amusing, and instructive exhibitions ever placed before the Boston public.

It was, observed the Boston Herald, “strikingly original and full of interest.” Bostonians patronized the show in such great numbers that the new grandstand proved inadequate. Salsbury instituted matinees to relieve the overcrowding when special trains brought thousands from the nearby towns of Lowell and Lawrence. To entice return visitors five weeks into its Boston stay, he introduced new song and dance acts.

The production ended its Boston stay in early September 1895, and Black America undertook a tour of other New England cities. In order to make one-night stands feasible, Salsbury was required to cut the number of cast members nearly in half. Still, even with this reduction, moving the massive Black America company was a logistical feat.

To convey the residual cast to subsequent venues, Salsbury ordered a special train of twelve white railroad cars with gold leaf trim and “Nate Salsbury’s Black America” emblazoned in red letters across the side. Nine sleeping cars could be converted for dining; a cooking and commissary car supplied meals; and a special car equipped with an office, private dining room, drawing room, bath, and three apartments made up Salsbury’s quarters. Like the Wild West show’s train of fifty-two cars, the picturesque convoy attracted plenty of attention and served as additional advertising.

After the company visited several more American cities, rumor had it that Salsbury would take the spectacle to London since he had received several tempting offers to do so. Stories in both the Boston Herald (July 28, 1895) and the Washington, DC Morning Times, (October 19, 1895) noted Salsbury’s opinion that Black America in London would be as much of a hit as the Wild West show.

For three weeks, the production played in Madison Square Garden in New York City, which was “much better adapted for this style of entertainment than was Ambrose Park. The voices of the singers are heard to greater advantage here than in the open air.” Black America headed to Philadelphia in mid-October where the Grand Opera House was transformed into a “Negro ‘quarter’ on a gala day and night, with the white folks from the ‘big house’ as the audience.” They, “probably with a few exceptions, saw for the first time the bright side of slave life.” The chorus of three hundred Negroes was recorded on a phonograph “that accurately reproduced the singing, the shuffle of the dancers’ feet, and the ‘patter’ that accompanied the buck and wing dancing.”

Washington, DC’s Convention Hall provided the next venue. The city’s Evening Star quoted Salsbury: “[T]hey sing in perfect harmony, and with an earnestness that can be brought out of no similar body of white people.” The enclosed space amplified and centered the voices so the music could be even better appreciated than in an outdoor arena. Salsbury continued:

Since I have been handling this entertainment, I have met the best people in every city, and they have expressed to me their surprise and gratification at the work produced by these negroes. In some of the larger cities, the newspapers have taken up the subject and treated it from an ethnological point of view. It has been a revelation to them, the precision and perfection of the work performed by these people of color.

Black America closes

After Philadelphia’s second two weeks’ engagement ended on November 23, and after a total of six months of performances, Salsbury disbanded the exhibition forever. It did not travel to London as anticipated, nor to any other U.S. cities, nor did it resurrect the next summer. Historians offer varied and sometimes contradictory reasons for its unexpected demise. Tarleton explained:

About the time the show was in Washington, Mr. Salsbury was taken sick and things went wrong so the show was disbanded, and all Negroes were sent home, and everything was sent back to Ambrose Park for storage…. Had Black America gone to Europe, Salsbury would have made a fortune.

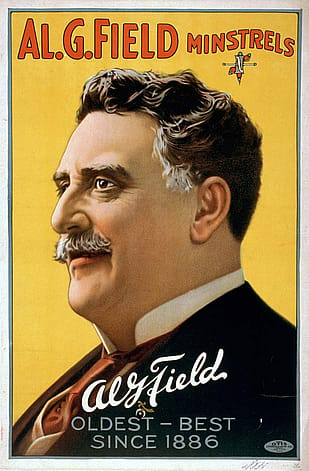

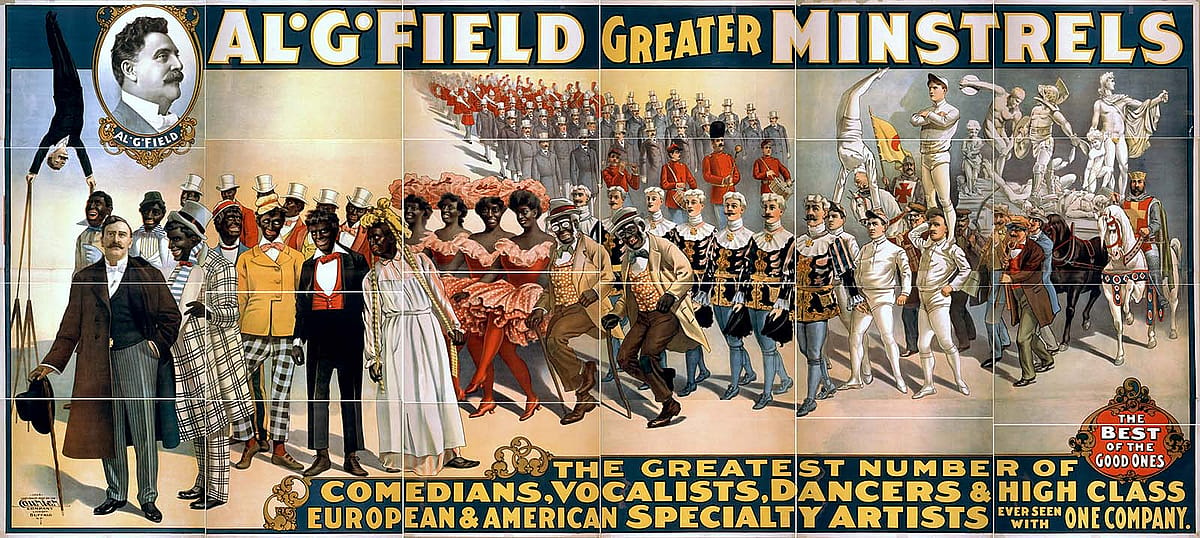

Perhaps frustration intensified Salsbury’s illness with the added stress of having to defend his exhibition against one Al G. Field (Alfred Griffin Hatfield). Field had appropriated the title Black America for his copycat program, even though Salsbury made it clear that the exhibition was his “sole and exclusive property.” If Field persisted using the title, Salsbury insisted he would not hesitate to “proceed again him…and hold him in heavy damages.” A weary-sounding Salsbury said:

Everything that I have invented is being plagiarized. They stole my ideas in the Troubadours, fliched [sic] from the Wild West, and now they are not only imitating Black America, but trying to steal my best people. It is disheartening, and I’m done.

Reports of insufficient patronage, despite most newspaper observations of overflow crowds, may have also been among the reasons for the closure. Were gate receipts enough to cover the extraordinary expenses of salaries and transportation of three hundred cast members, scenery, and a whole village? Clearly disappointed, in one of his letters home, Cody told his wife that he had lost $10,000 on Black America.

Four years later, Cody and Salsbury were still blaming each other in vitriolic correspondence for the show’s failure. Cody claimed $78,000 was lost “through speculations of [Salsbury’s] suggestions.” Salsbury retaliated by reminding him that Cody approved of Ambrose Park, that he approved of Black America, and that, though Salsbury wanted to close it earlier, Cody had insisted on keeping it going.

Looking back

Nate Salsbury used his theatrical interest and business savvy to stage a novel exhibition of pre-Civil War slave life, recognizing that the program would seem appealingly exotic to New England audiences. Drawing on a tumultuous partnership with Buffalo Bill Cody and the experience the two had gained in the promotion and execution of their Wild West, Salsbury and Cody knew that for such a venture to be successful it needed to present authentic scenes and use actors who had lived the experience.

So, although Black America may appear exploitative to a twenty-first-century majority, it presented antebellum culture to thousands of northerners; furnished employment for, at times, more than five hundred performers; and showcased the talents of many individuals. As was frequently observed, Nate Salsbury’s Black America “must be numbered among the successes of the century.”

About the author

Sandy Sagala is currently a member of the Papers of William F. Cody Editorial Consultative Board and has contributed several stories to Points West. She has also authored four books about William F. Cody, including Buffalo Bill on Stage and Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen. In spring 2019, University of Kansas Press published Buffalo Bill Cody, A Man of the West, written by Prentiss Ingraham and edited and introduced by Sandra K. Sagala.

Post 282

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.