Understanding the Yellowstone Fires of 1988, Part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2016

Understanding the Yellowstone Fires of 1988, Part 2

How the Fires Affected American Culture and How Culture Affected the Fires

By John Clayton

“For many people in the Rockies and northern plains, the Yellowstone fires of 1988 are a watershed event like the assassination of John F. Kennedy or the 9/11 attacks,” wrote John Clayton in the last issue of Points West. “Distinct memories of the freakish weather, the smoky haze, or the national media attention lock the summer in time.”

By as he contemplated all three events, Clayton wondered how the fires compared to the Kennedy assassination, or 9/11 for that matter, with respect to their effect on society—from culture and media coverage, to government agency management and philosophy. In Part 2, Clayton suggests that, historically, Yellowstone has always carried many layered meanings for Americans—and “the 1988 fires threatened them all.”

Burning values and ideals

In 1988, 775,000 acres burned in Montana outside Yellowstone National Park—almost as much as inside the Park. In the Bob Marshall Wilderness, five hours northwest of Yellowstone, the 250,000-acre Canyon Creek fire burned bigger than any of the individual fires in Greater Yellowstone. But that particular fire didn’t make big national headlines. The reason? The national media story wasn’t so much about the issues discussed in Part 1 of this story: burning forests, fire ecology, and suppression techniques; nor was it about ecosystem-centered vs. human-centered views of nature. It wasn’t even about how to live in a post-Vietnam world. The Yellowstone fires grabbed the nation’s attention precisely because they were about Yellowstone—because Yellowstone had come to embody a set of deep national values.

Throughout American history, Yellowstone has had many, layered meanings: a remnant frontier; an animal sanctuary; a patriotic mecca; a spiritual retreat; and a vision of what earth was like without humans. The fires threatened them all.

Yellowstone: the frontier without the danger

For most Americans, Yellowstone represents wide-open spaces and lands minimally impacted by development. That makes it a place to experience the nineteenth-century pioneer spirit—to recapture the era when Americans first started taming such landscapes.

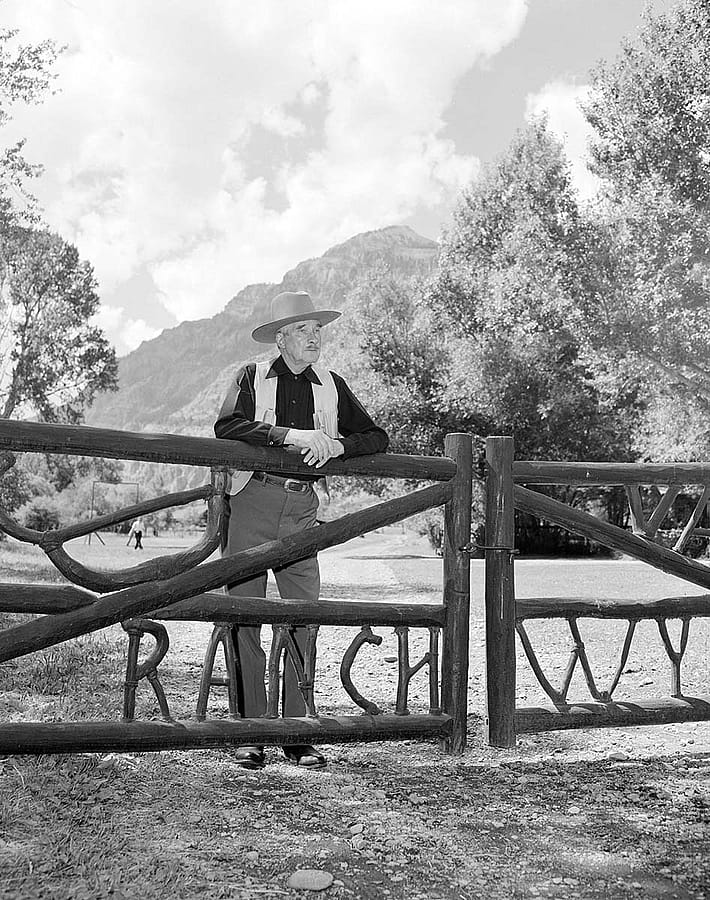

People come to Greater Yellowstone to celebrate the independent, masculine, tough, deep character of heroes such as Teddy Roosevelt, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Calamity Jane, and their victory over a harsh frontier environment. Thus a Yellowstone vacation often involves activities celebrating homesteads, cattle roundups, and prospecting for gold—even though the national park has always banned such endeavors within its boundaries.

That’s what fueled the Greater Yellowstone dude ranch boom of the 1910s and 1920s. Although dude ranches have come to be associated with oversized cowboy hats and toy six-guns, the great innovation of entrepreneurs such as Larry Larom, Howard Eaton, and Struthers Burt was more basic: They re-created the frontier without the danger. You could fish, hunt, ride horses, attend rodeos, mingle with cowboys, and enjoy an outdoor lifestyle in a beautiful wide-open place—without ever having to worry about Indians, bandits, or grizzlies. This Greater Yellowstone country was wilderness without all those dangerous elements that kept people out of wilderness. And although the affection for cowboy paraphernalia and culture is shrinking, the vision of a safe frontier still draws crowds today.

Yet one of those dangerous elements, absent from Yellowstone for much of the twentieth century, was wildfire. In 1988, with fires running rampant, how could we celebrate the way we had tamed the wilderness?

Yellowstone’s status as a preserve

Soon after Yellowstone’s founding, it was beset by poachers. The struggles of the 1870s and 1880s were to first ban hunting, and then develop capabilities to enforce that ban.

By the late 1890s, Yellowstone had achieved status as a preserve, where endangered species such as bison might be saved from extinction. Yet for many conservationists of the time, Yellowstone’s meaning was greater than mere wildlife habitat. For example, Ernest Thompson Seton, a popular author and illustrator best known as a co-founder of the Boy Scouts, wanted to change the relationship between people and animals. He hoped to atone for wanton slaughter—including his own acts in his younger years—and develop a spiritual bond. He hoped that by creating a sanctuary for wildlife in Yellowstone, we could make those animals at least “half tame.”

In that era, the notion that animals might lose their fear of people was magical. Thus, for example, naturalists paid more attention to the bison that Eaton had relocated from his North Dakota dude ranch to Yellowstone—a zoo at Mammoth and later a ranch in the Lamar Valley—than to a still-wild herd roaming the Mirror Plateau. These half-tame bison were the ones we’d saved, the ones we’d protected. That relationship—the way heroes such as George Bird Grinnell had seen these animals’ weakness and granted them sanctuary—was paramount. In the last century, ecologists have come to see animals’ wildness as a virtue, but for much of the general public the traditional, “sentimental” view still holds appeal.

So in 1988, a wildfire threatened these helpless creatures in the sanctuary we had created for them. There was no data on how they were faring. (In retrospect, surprisingly few were killed, but in 1988 nobody knew that—indeed rumors insisted on a cover-up.) Given the crisis, how could we celebrate our stewardship of these wild creatures?

Saving Yellowstone for all the people

For the decade after its founding in 1916, the Park Service played up a fable: That the “national park idea” emerged around an 1870 campfire at the confluence where the Gibbon and Firehole rivers combine to make the Madison River.

Yellowstone was indeed the world’s first national park, but this story stretched the truth in linking that idea to a patriotic campfire conclave. In the fable, a set of idealists who could have pursued riches by placing homestead claims at Old Faithful, instead invented a “national park” as a way to dedicate these wonders to democracy. Saving this special land for all the people, not just the rich or powerful, was what made this country different. Furthermore, the fable highlighted America as a special country that anchored its ideals in landscapes, rather than military might or racial characteristics.

In 1988, the fires threatened this patriotic association. “Part of our national heritage is under threat and on fire tonight,” Dan Rather said on the CBS News on September 7, 1988. A sensationalized view would see “destruction” of the world’s first national park (including the Madison confluence) caused by “tyrants” who deemed ecological ideas more important than patriotic sites.

A spiritual connection to Yellowstone

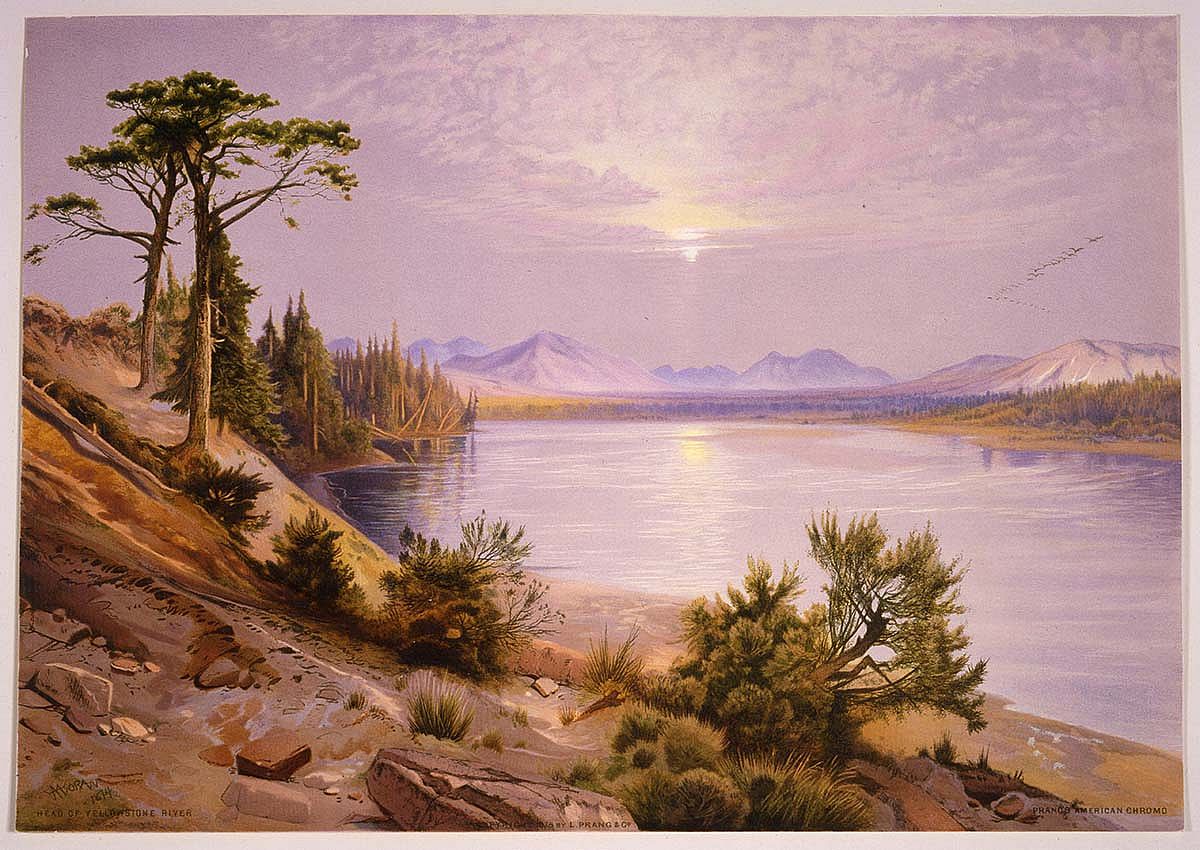

As the twentieth century progressed, many people preferred to see Yellowstone not as frontier, representing the conquering of wilderness, but as wilderness itself. When Ansel Adams photographed Yellowstone Lake, where untouched forests came down to the edge of the still, expansive waters, with a distant background of silent, snow-capped mountains, people felt a spiritual connection to the vastness of that scenic beauty.

They also expected that scenic beauty to endure forever. Yellowstone was timeless and enduring; nature was more permanent than the temporary presence of any individual. As a 1980s brochure from a park concessionaire described it, “Yellowstone’s spring, summer, fall, and winter seasons recreate their ageless panorama.” It was easy to jump from these notions to the idea that Yellowstone would never change. Yet in 1988, the fires were burning those landscapes, changing them—”Old Faithful will never be the same,” wrote the Chicago Tribune—and threatening those spiritual connections.

For most people, the deep spiritual connection is with natural beauty, defined in terms of colors and symmetry. But for ecologists, the connection is with nature, a set of processes and changes including fire. Thus the two groups often talked past each other. During the 1988 fires, Yellowstone Superintendent Bob Barbee told the New York Times Magazine, “Yellowstone is not fixed in formaldehyde and should not be fixed in time. It was born in a cataclysm.” It was an important message, but one that differed from popular images.

Ecologist Don Despain was even less in sync. As he looked over a piece of scorched earth in the spring of 1989, he said, “If we can overcome our biases, we can see beauty in this scene.” Those biases for natural beauty were what had established Yellowstone as a national park in the first place—and the (biased) spiritual connection to that beauty was what the public saw the fires destroying. Ecologists, who see beauty in process, fulminate at that word “destroyed,” because fires are part of the process, but when colors and forms burn, others see beauty destroyed.

Yellowstone: nature without people

Most importantly, Yellowstone stood as a symbol for nature without people. For example, following the Leopold Report of 1963, the Park Service saw its mandate as preserving a “vignette of primitive America.”

One appeal of a “let-burn” fire policy was that it mimicked what had happened at Yellowstone before Anglos arrived on the scene. To look at Yellowstone’s recorded history was to see continual efforts to set this place aside from destructive qualities of American culture—railroads and industrialism, poaching and hunting, private property and development, unattended campfires and carelessly discarded cigarettes. A widespread belief that these activities could harm “nature” led to defining nature as separate from them. A belief that Yellowstone’s nature was separate from humans egregiously ignored the long-term presence of Native Americans. Or perhaps this view tried to see ancestral tribes as somehow “pure” and part of this natural world, a more charitable but still condescending attitude.

The path was tricky, but the destination was glorious: You could come to see Yellowstone as the Garden of Eden. Deeply held cultural narratives taught Americans that any place dominated by nature was a place of harmony. These were places from which we had been banished because of our original sin. Original sin dictated that we couldn’t help ourselves and would always end up destroying the places we loved. This sentiment was present at the founding of Yellowstone: We needed a national park because souvenir shacks had destroyed the wonder of Niagara Falls. The sentiment has been present ever since. As American West Travel and Life, a magazine for RV enthusiasts, put it, “Yellowstone and other national parks are precious natural places where human intervention should be kept to a minimum. Look what we’ve done almost everywhere else.”

Original sin is theologically tricky. If we always destroy the places we love, then we might do so not only through ignorance, but also through good intentions such as the desire to create a naturally pure haven. If humans are inherently flawed, then we can never successfully create a place to be set aside from our own influence. Any human-led project to construct a Garden of Eden is by definition doomed, much as we hate to admit it. So, as fires burned through Yellowstone in 1988, we saw our original sin playing out in this special place we had tried to preserve from it, and we recoiled in horror.

What we didn’t talk about: climate

The cultural values of Yellowstone Park, along with the cultural milieu of the post-Vietnam era, were thus the driving forces of 1988 media coverage. That’s why the media didn’t portray the science of fire ecology as accurately or prominently as ecologists would have liked.

But in retrospect, an even bigger scientific story was even more widely ignored. Nothing in the extensive collection I studied, not even articles in conservation-oriented magazines such as Audubon, addressed climate. (NASA climate expert James Hansen did testify before the Senate in June 1988, and was quoted in an October Discover magazine cover story, about “the greenhouse effect.” But Hansen never mentioned Yellowstone, and the 1988 fire stories rare mentions of climate involved only questions about whether smoke from the fires might resemble that from a nuclear war, and whether such a “nuclear winter” would be climate-chilling.)

The most admirable 1988 media coverage addressed issues such as the inherent weakness of containment lines in the face of unpredictable fire behavior patterns, or the century-long fuels buildup due to successful suppression campaigns highlighted by Smokey Bear. But even these didn’t get at the root cause of the fires’ intensity. Fires raged because the summer involved hardly any rain, incredibly low humidity, incredibly dry trees, and incredibly strong winds that repeatedly pushed sparks to new tinder. It was all about the weather. And one year’s weather might be a freak occurrence, but when weather trends accumulate, we call them climate.

1988 fires, a watershed

The 1988 fires were presumed to be a once-in-a-lifetime event. Not since fire destroyed three million acres in the Big Blowup of 1910—eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana—had the country seen anything like them. In 1988, sending 25,000 firefighters to Greater Yellowstone was unheard of. The $120 million price tag seemed extraordinarily high. Yet one-third of the years since then have involved at least 25,000 firefighters deployed nationwide. In 2013, nationwide firefighting expenditures exceeded $1 billion.

Granted, firefighting budgets have increased because of increases in the wildland-urban interface; we spend more money today fighting fires because we keep building houses potentially in their way. But acreages trend the same way. The 1988 fires burned 1.7 million acres in Greater Yellowstone and about 5 million acres nationwide, which seemed quite high at the time. But half the years since have involved more than 5 million acres of burns, with three years exceeding 9 million acres. Indeed, eight of the nine worst fire years since 1960 have taken place since 2000.

The trends point to a changing climate, and ecologists now worry that global warming will create its own problems. Although under current patterns most forests in Greater Yellowstone burn every hundred to three hundred years, climate change could reduce that cycle, according to one model, to less than thirty years. Such a change in fire regimes could change the types of plants that exist here, with implications for the animals that eat those plants as well. Nationwide, a changing climate could also exacerbate the wildland-urban interface. As historian Stephen Pyne put it, “Climate change may flip the script of people constructing houses where fires are, with fires instead coming to where houses are.”

Rocky Barker and Todd Wilkinson were journalists in Yellowstone in 1988, and both of them were almost trapped by the oncoming fire at Old Faithful on September 7. “We thought the wall of flames, the firestorm at Old Faithful, and the fire behavior was extraordinary that day,” Barker told Wilkinson in 2013. “Twenty-five years later it has become routine in the West. It was the signal fire of climate change.”

Some climate activists ask what it will take for the general public to appreciate the science of climate change, to become as worried about its long-term effects as the scientists are. Maybe, they say, it would take some big, scary personal nightmare, one that’s visible, and memorable, and shared by a wider community—one that feels like a watershed event. What’s most surprising, then, about looking back at the 1988 Yellowstone fires is realizing that every westerner past the age of 27 has lived through such an event, and nearly all of us failed to appreciate it.

About the author

John Clayton is an independent journalist, essayist, and corporate ghostwriter based in Montana. In his essays, articles, and books, he’s tackled subjects as diverse as western history and lifestyle, business writing, small town politics, and biographies of western notables and the nearly-forgotten westerners. Clayton has taught at Rocky Mountain College, is on the advisory board for the Montana Center for the Book, and was a Center of the West research fellow. In 2016, he served as Visiting Writer-in-Residence at Montana State University-Billings.

Post 284

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.