The Life and Work of Will James – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2019

The Life and Work of Will James

By Nicole Todd

The life of Will James is one of both mystery and mayhem. His work, however, tells the story of a life he was meant to live.

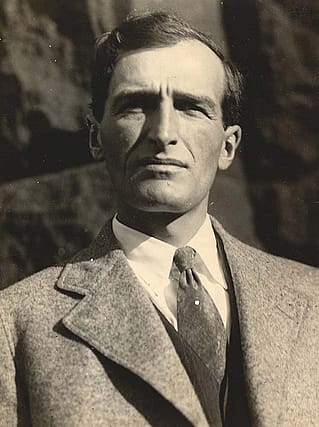

Born Joseph Ernest Nephtali Dufault on June 6, 1892, in the Québec parish of Saint-Nazaire-d’Acton, the boy grew up yearning to be a cowboy. Exposed to stories of cowboy life and the North American West in his youth, Dufault headed to western Canada in 1907 to fulfill his dream.

In 1910, believing he had killed a man, Dufault fled for the United States. He adopted several aliases before settling, for reasons now unknown, on William Roderick “Will” James. He even created a backstory for himself—where he came from, what happened to his parents, and why he spoke broken English. His self-taught grammar and, subsequently his writing later in life, gave merit to his fabricated personal history. During his travels James managed to steal cattle, survive jail and a hospital stay, and attend art school. These events, and the people he encountered along the way, played an important role in his decision to become a full-time author-illustrator.

![Will and Alice James, Washoe Valley cabin [NV], ca. 1923. Mountain West Digital Library, Digital Public Library of America. University of Nevada, Reno Libraries Digital Collections. UNRS-P2270-20](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=354,height=470,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PW289_WillAliceJames_RenoLibraries_UNRS-P2270-20.jpg)

By the time James became a cowboy in the early 1900s, the effects of barbed wire and the expansion of farming in the American West had broken up most of the large-scale ranching operations into stock farms. At the same time, the emerging automotive revolution began to impact roundups and the role horses played on the range. The industrialization and automotive expansion into the West affected James’s perception of what it meant to be a cowboy.

Pining for the Old West, James illustrated the American cowboy before the effects of barbed wire and the automotive revolution took place. His art not only served as illustrations for the books and short stories he wrote, but also helped shape and extend the historical, cultural, and mythological perceptions of the cowboy-hero in American culture during the early twentieth century. In his depictions, the cowboy is almost invariably accompanied by horse and cattle. To James, the three were indispensable to his way of life.

Making a hand

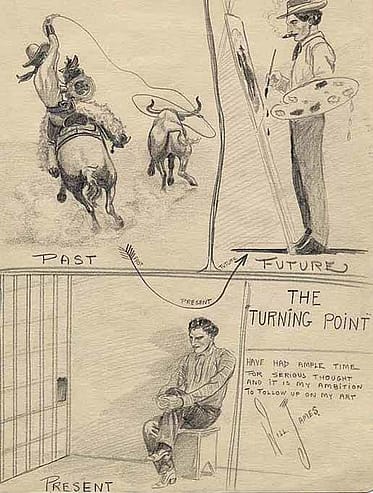

In 1914, James was imprisoned for stealing cattle in Ely, Nevada, and sentenced to seventeen months in jail. He included in his application for parole a sketch he titled The Turning Point. The small vignettes bear individual titles, “Past,” “Present,” and “Future” and demonstrate various stages of his life.

A cowboy on horseback roping a steer depicts the artist’s “past”; a drawing of a solitary prisoner seated on a stool, his “present”; and the “future” portrays a cigar-smoking James, palette in hand, standing at an easel, painting. In the lower right corner of the drawing James inscribed “Have had ample time for serious thought and it is my ambition to follow up on my art.” Although these drawings signified a change in James’s perspective on life and his outlook on the future, it is unclear if his artistic expression of remorse and renewal influenced his release from prison. Nevertheless, James was set free on April 11, 1916, only to continue his nomadic lifestyle. James pursued the life he had come to love for another three years until a bucking horse accident in 1919 sent him to the hospital. The mishap sidelined his occupation as a working cowboy and inadvertently launched his career as an author-illustrator. Impressed by some of James’s sketches, a fellow hospital patient provided James a letter of introduction to the associate editor of Sunset Magazine.

Upon his release from the hospital, James enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco where he met fellow artists Harold von Schmidt and Maynard Dixon. Both Dixon and Von Schmidt assisted James, providing contacts with publishers and suggesting useful materials for drawings and paintings. But James bridled at the demands of the school’s curriculum, and it was with Dixon’s encouragement that James quit attending classes to pursue a career in illustration.

It was these connections—and the letter of introduction—that resulted in James’s first published drawing, A One-Man Horse, which appeared in the January 1920 issue of Sunset Magazine. The seventeen-page article launched James’s career as an author-illustrator with the promise to publish more of his work. In time, he succeeded in placing his work in some of the most popular periodicals of the day, including Saturday Evening Post and Scribner’s Magazine.

In 1923, James sent an illustrated article to Scribner’s Magazine. Seeing potential in James’s works, the magazine offered him a contract for a self-illustrated book titled Cowboys North and South. During the next two decades, James would write and/or illustrate more than twenty novels and anthologies of short stories on cowboy life, virtually all of them based largely on his own life experiences.

James’s work can often be characterized as simplified with crisp draftsmanship. He worked in several media throughout his career—pencil, pen and ink, and oil. However, by “using pencil, as opposed to ink, James was able to make a stronger, more powerful depiction of his action scenes,” according to art collector Abe Hays in Will James: The Spirit of the Cowboy, a 1985 catalogue of the artist’s work from the Nicolaysen Art Museum in Casper, Wyoming.

![James's work can often be characterized as "simplified with crisp draftsmanship" as in these sketches from Watched by Wild Animals, [Enos A. Mills, New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1922; not published]. Cabinet of American illustration. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA. "Looking for Small Favors." 2010716934 / "Coyote, Clown of the Prairies." 2010716932 / "The Mountain Lion." 2010716933](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1323,height=771,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PW289_JamesAnimalSketch-collage_LOC.jpg)

By romanticizing his own experiences and the stories he had heard, James personalized and tailored his own version of the cowboy-hero. “James wanted the world of the cowboy to be appreciated for its realities and its values as he understood them,” Hays added. In order to express such truths, James’s cowboys rarely resorted to the sort of theatrics and fatal gunplay that artists Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell depicted.

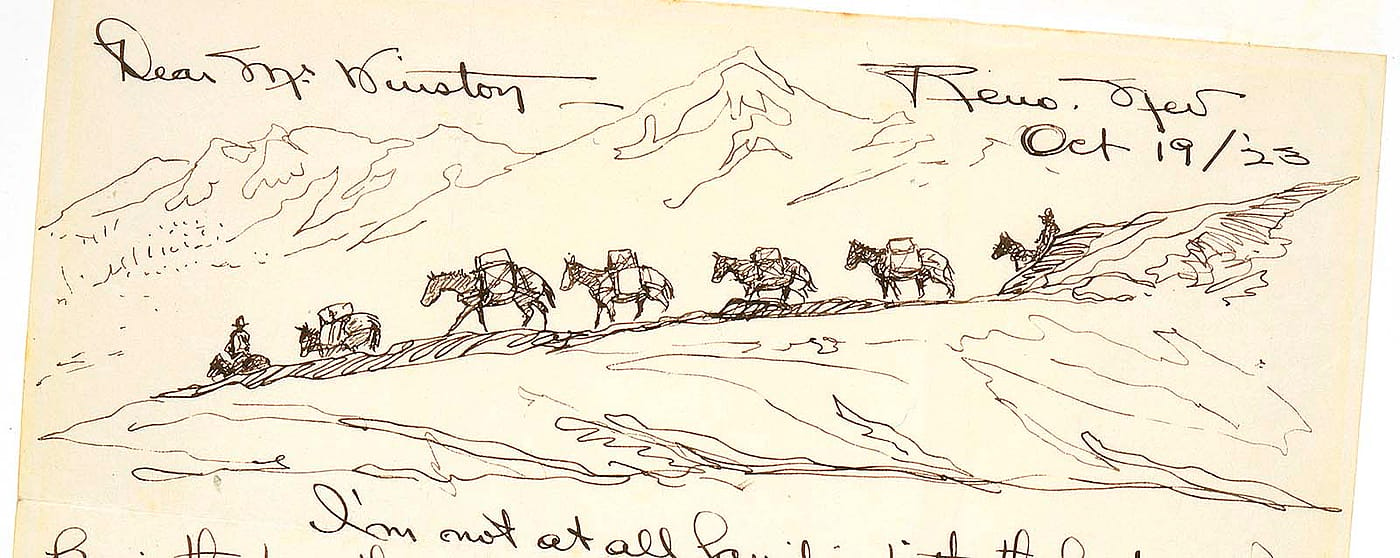

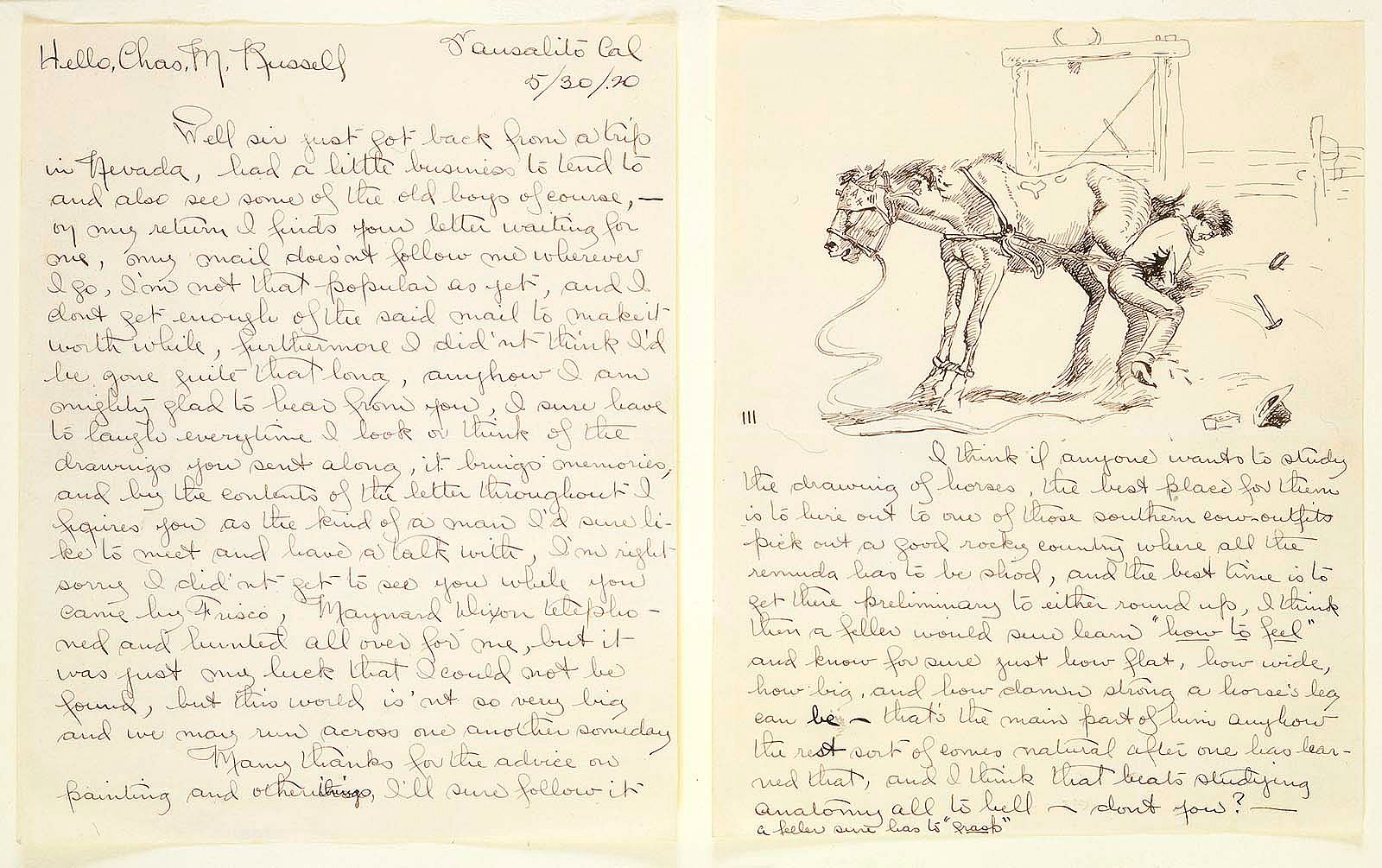

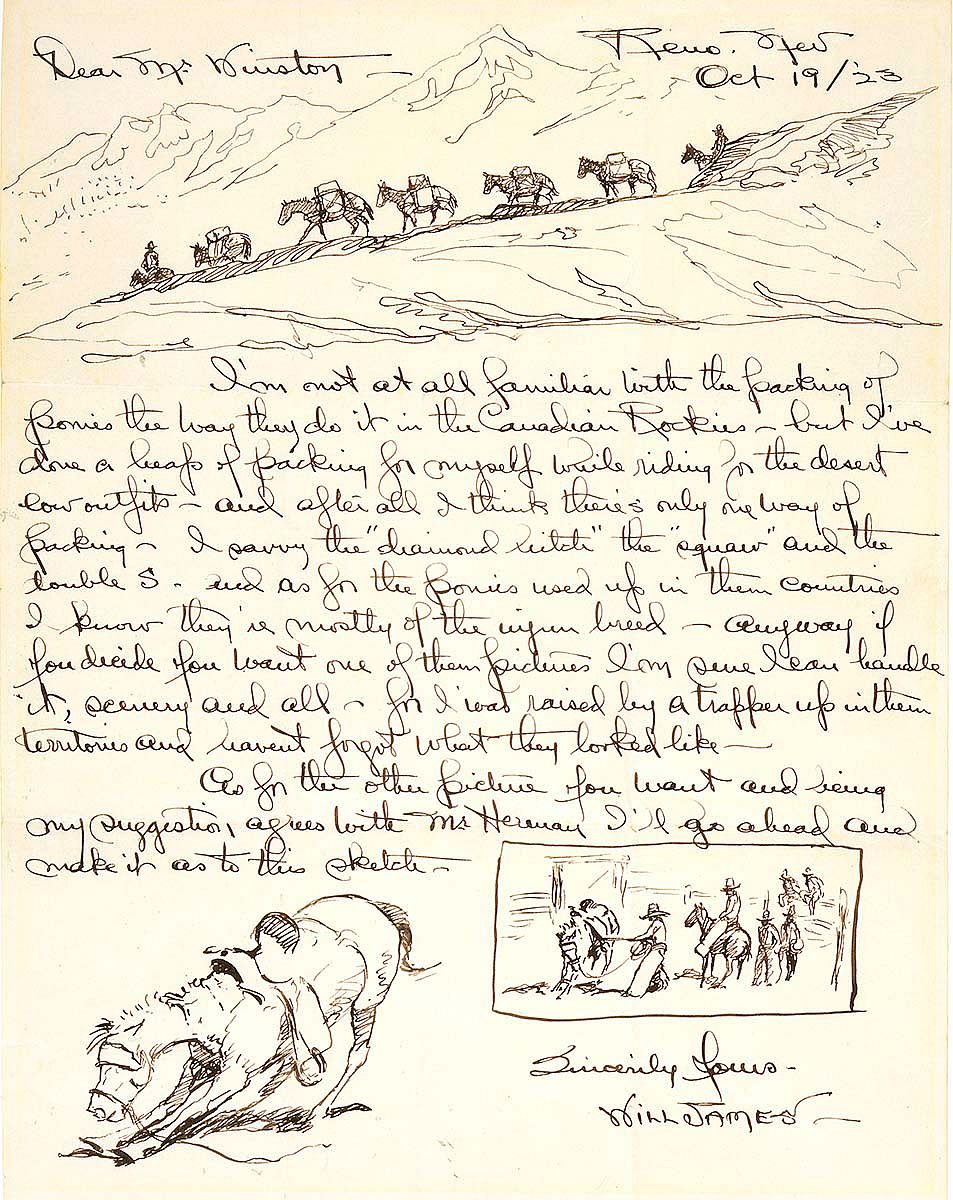

Despite Remington’s impact in the western American art world, no artist was more influential on James than Russell. Through the years, the two became good friends, and it was this friendship that inspired James to imitate Russell’s illustrated letters and seek advice and encouragement from the veteran artist on several occasions. Horses were a regular feature of James’s illustrated letters. His illustrations almost always reinforced the text—a practice he borrowed from Russell. It was Russell who encouraged James to paint as well as draw and urged him to continue to focus on cowboys, horses, and cows.

In a letter penned to Charles M. Russell, on April 11, 1920, James showcased a pen and ink drawing titled, I’m Riding an Artistic Steer, and Doing My Best to Put the 111 on His Shoulders. The loose pen strokes suggest James sketched the illustration spontaneously. The illustration and caption reinforce the text and hint at some of the difficulties James faced as an artist and illustrator. The steer’s expression and body contortion suggest distress, confusion, and uncertainty—all qualities James expresses in the body of the letter. The phrase “trying to put the 111 on his shoulders” refers to James’s desire to make his mark on his profession, much as a rough rider’s spurs often left scratch marks on the hide of a horse or bovine.

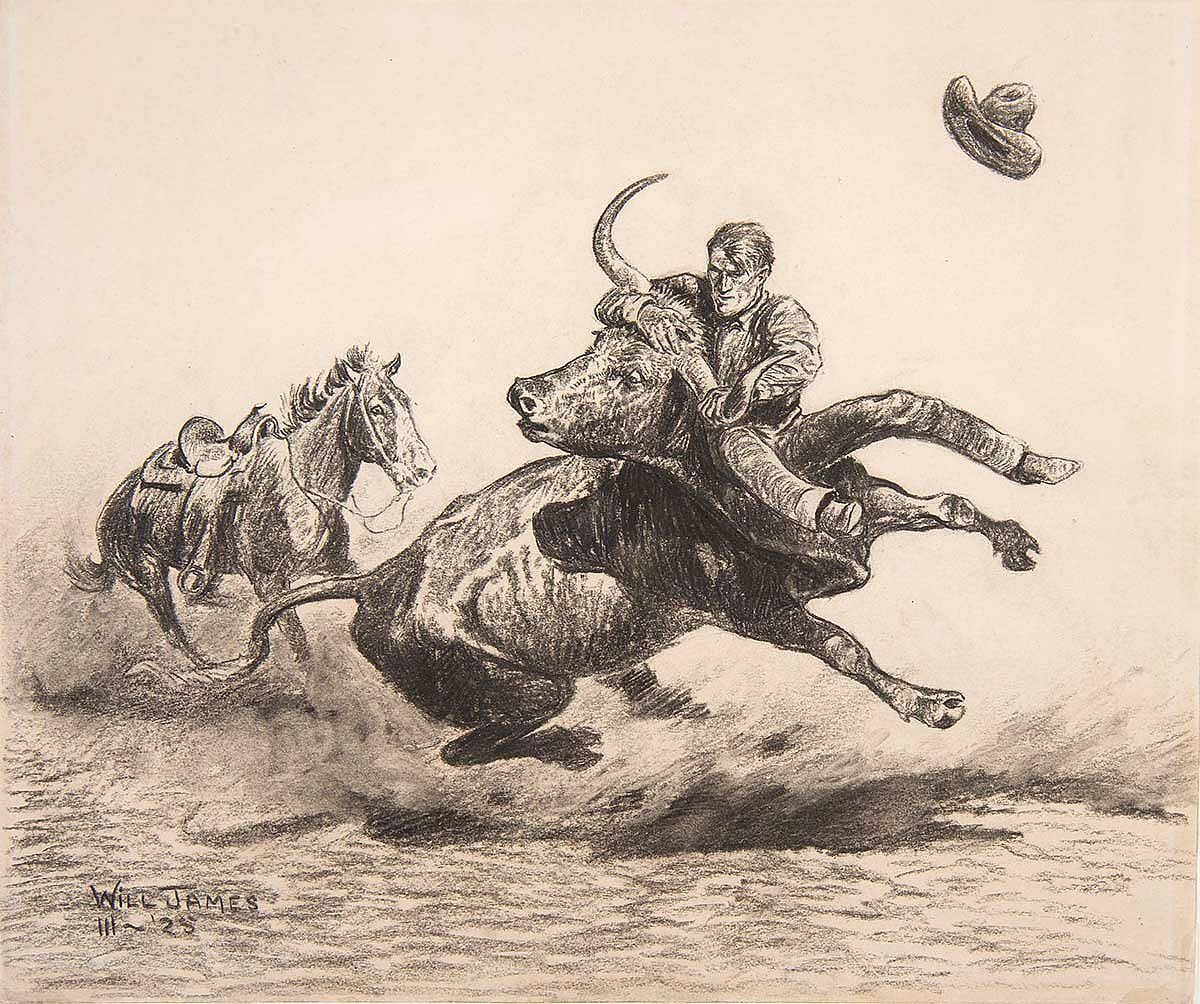

Another of James’s drawings, Steer Wrestling, alludes to the difficulties of working with wild range cattle. The cowboy holds on to the cattle’s horns as he tries to gain control of the animal. In this case the cowboy is the artist himself. The determined look upon the cowboy’s face suggests the struggles James faced in his career and personal life. This work is a reminder of the crucial roles that both horse and cattle played, and demonstrates the realities of the cowboy profession.

Painting the cowboy

Although his pencil, and pen and ink illustrations drew as much praise as his writing during his career, James’s oil and watercolor paintings were little known or appreciated, especially compared to his drawings. Furthermore, they were overshadowed by the canvases of William H. Dunton, W.H.D. Koerner, and William R. Leigh, among other artists and illustrators of the West active in the 1920s and 1930s.

James often chose to portray the physical and emotional interactions of and between cowboys and horses. The violence and hostility that often accompany the breaking and training of range horses, however, are the centerpiece to some of his most dramatic scenes, including the painting Where the Bronco-Twister Gets His Name (1924) [view this artwork in The Gilcrease Museum’s online collection]. The interaction between man and beast is obvious as a cowboy clings to the horse’s head while the horse violently bucks. Thus, this is where the bronco-twister gets his name. His ability to cling to the horse during the act of bronco bucking has earned him a title worthy of admiration.

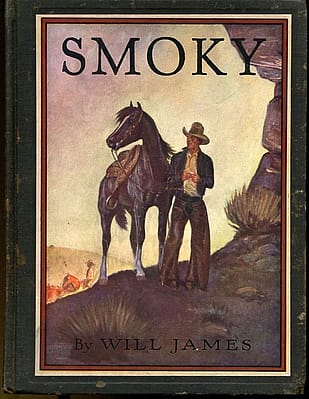

His first novel, Smoky the Cowhorse, published in 1926, thrust the author-illustrator into the front rank of interpreters of the cowboy West. Smoky and Clint, a color plate from Smoky the Cowhorse, depicts the main characters of the novel in a moment of quiet reflection in the shade as a cattle drive passes in the distance. Unlike many of his other drawings and paintings, James chose to portray a side of the cowboy most viewers often neglect, reminding his audience the cowboy’s life can often be isolated and lonesome.

If 1926 was the year that pushed Will James into the spotlight, it was 1929 that built upon his newfound popularity. Charles Scribner’s Sons published his new novel, Sand, which would prove to be one of his most popular stories, and reprinted Smoky the Cowhorse in an Illustrated Classics Edition that included his oil painting Smoky and Clint on the front cover.

The debilitating effects of alcoholism had begun to take their toll on the quality of James’s work by 1937 when he was first hospitalized for the disease. As his pen and pencil strokes became less steady, James’s horses, once the epitome of muscle and motion, began to look skinny and stiff. Although the illustrations clearly declined in quality, some of James’s best portrayals of cowboy life in word and image occur in his last book, The American Cowboy, published in 1942, the year of his death. The illustrated volume addresses the history and iconography of three generations of western cowpunchers and discusses the significance of their legendary counterparts as the West gradually changes from a dangerous frontier to a settled landscape. Despite the rapid pace of change, James was optimistic that working cowboys would always persevere, if not in reality, in the imagination. He ended The American Cowboy with one simple yet resolute sentence: The cowboy will never die.

Influence for the ages

Despite achievements that helped sustain his name within the art community, James remains largely forgotten. Several factors have contributed to his decline in popularity. Foremost is the fact that most of his output was created to illustrate magazine articles and children’s books. Little, if any, of his work was created with the art collector’s market in mind. Economic factors, particularly the Great Depression, also played a role, severely depressing the fine art market at the very moment that the artist’s popularity was on the rise.

Marginalized to the far corners of western American art, James’s work endures, inspiring a new generation and creating a love for the old West. Several of James’s books, including Smoky the Cowhorse, Sand, and Lone Cowboy, were made into films. Beyond film adaptations of his work, James has been the topic of more than one documentary, including Alias Will James (1988), written and directed by Jacques Godbout, and The Man They Call Will James (1990), by Gwendolyn Clancy.

James’s art, correspondence, and artifacts are found in private collections and several museums across the American West, including the Yellowstone Art Museum, Billings, Montana; the Big Horn County Historical Museum, Hardin, Montana; the Northeastern Nevada Museum and the Western Folklife Center Wiegand Gallery, both in Elko, Nevada; the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; the Phippen Museum, Prescott, Arizona; and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Not surprisingly, relatively little Will James material exists east of the Mississippi River. A notable exception is the archives of James’s publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons, held at the Firestone Library of Princeton University in New Jersey, which houses correspondence, contracts, and other information related to his books and illustrations.

Despite his obscurity, the writings and art of Will James inspire musicians and artists of today. James’s own embodiment of the mythic cowboy is celebrated by Canadian singer-songwriter Ian Tyson in his 1988 song, Will James. Montana sculptor Bob Scriver once stated, “When I was getting started, and with many other artists trying to break into the art field, all of us tried to draw horses like Will James and not Charles Russell.” Although Will James is no longer a household name, his impact is still felt in the work of contemporary artists of the American West.

Following in the artistic footsteps of Remington and Russell, James became one of the most influential western artists and writers of his generation, and was one of the principle factors in guiding the public perception of the American West and the cowboy-hero during the 1930s. Will James assisted in creating one of the greatest stories America has ever produced—the story of the American West and its cowboy-hero in the final days of the open frontier.

About the author

Nicole Todd is the Curatorial Assistant for the Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum. She holds a BS in zoology, a BA in art history, and an MA in art history from the University of Oklahoma. Her master’s thesis topic covered the works of Will James and his contribution to the mythology of the American cowboy. Her research spans a variety of topics including nineteenth-century artist-explorers, the Golden Age of Illustration, and the Taos Society of Artists. Todd assists Whitney Curator Karen McWhorter in object curation, exhibition, and research. She uses social media to take the collection beyond the walls of the Center, and is a Certified Interpretive Guide through the National Association for Interpretation.

Post 289

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.